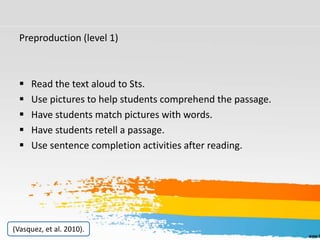

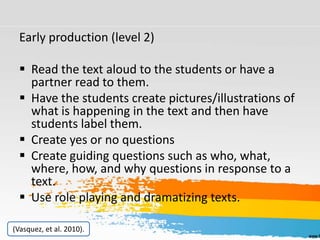

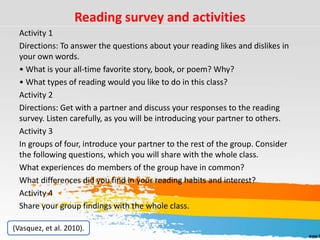

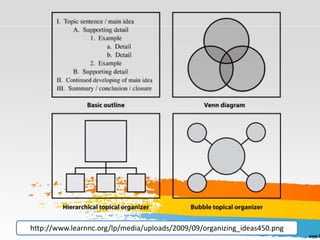

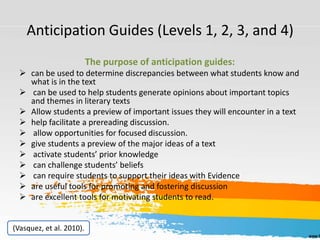

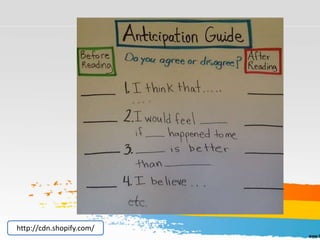

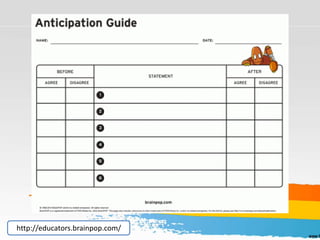

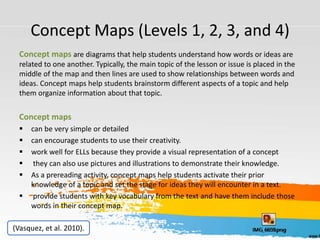

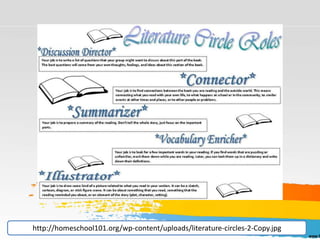

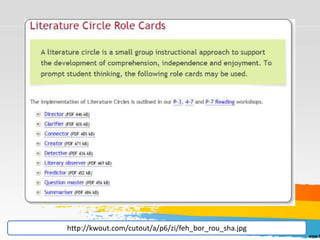

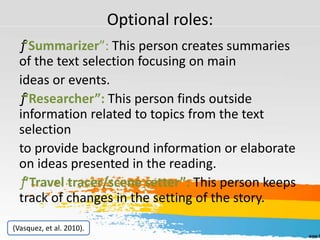

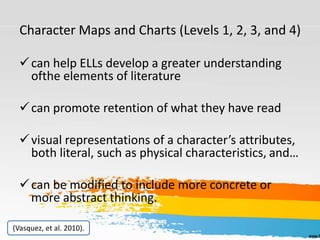

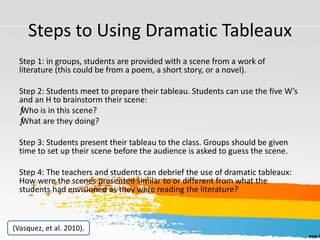

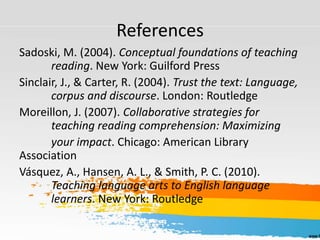

This document provides strategies and processes for effective reading at different levels. It discusses activities teachers can use before, during, and after reading to help students comprehend texts and practice reading strategies. Some key strategies mentioned include using graphic organizers and anticipation guides before reading, talking to the text and double entry journals during reading, and literature circles after reading. The purpose is to teach students a "toolkit" of approaches to help them actively engage with texts at an appropriate level for their language development.