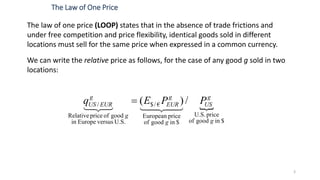

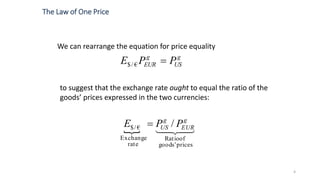

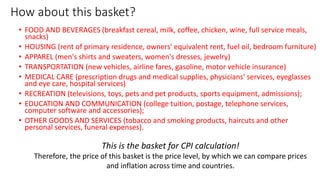

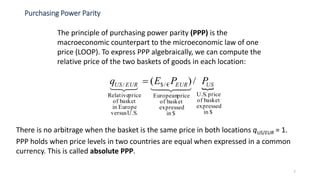

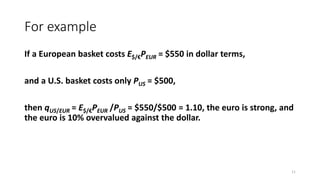

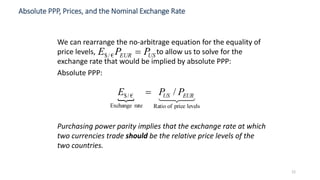

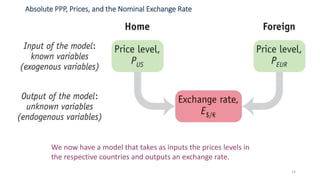

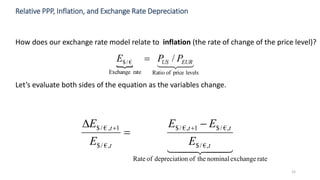

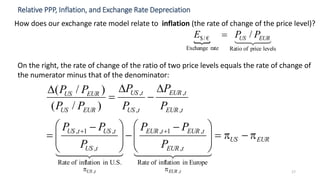

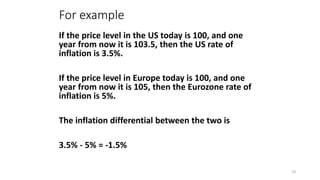

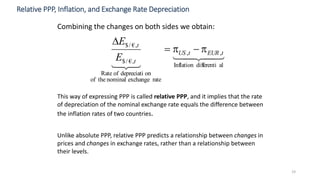

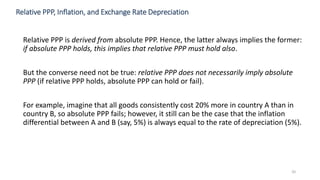

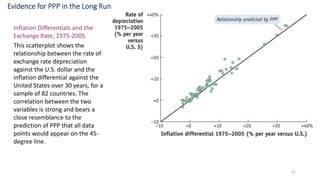

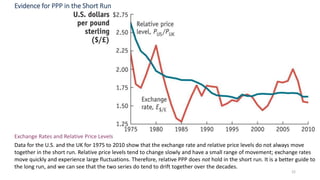

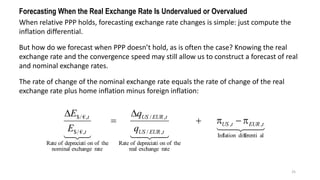

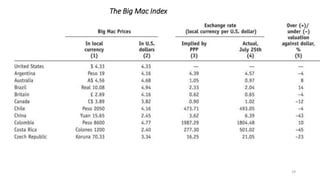

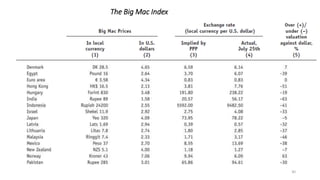

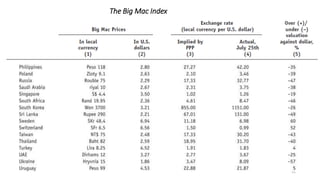

The document discusses the theory of purchasing power parity (PPP). It defines PPP as the principle that identical baskets of goods should have the same price when expressed in a common currency if not for trade barriers. Absolute PPP suggests prices levels should be equal across countries, while relative PPP suggests inflation differentials should equal exchange rate depreciation. The document provides examples of how PPP can be used to estimate exchange rate levels and changes. It also discusses factors like transaction costs and non-traded goods that can cause deviations from PPP in practice.