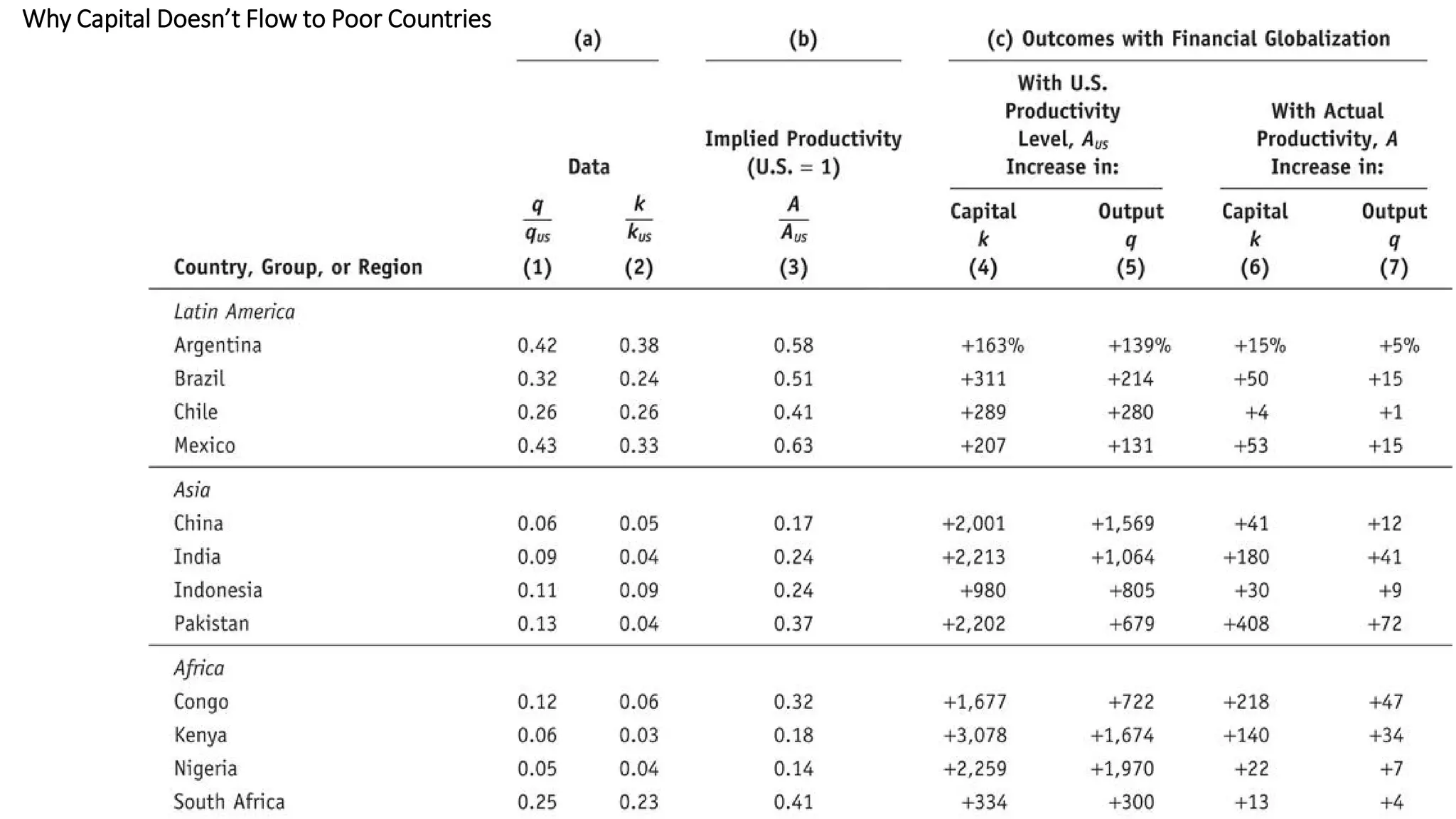

This document discusses Robert Lucas's paradox regarding why capital does not flow from rich to poor countries despite higher returns. It summarizes that:

1) Poor countries have lower productivity (different production functions) than rich countries, resulting in a smaller difference between rates of return that reduces the incentive for capital to migrate.

2) Allowing for productivity differences, investment will not cause poor countries to reach the same capital or output levels as rich countries, leading to long-run divergence rather than convergence.

3) Unless poor countries can increase productivity, greater financial integration provides limited benefits, as there are not enough opportunities for productive investment to drive complete convergence.