This literature review examines project controls and their importance in project management. It discusses the key bodies of knowledge and nature of project control, highlighting planning, scheduling, cost control, change management, and performance measurement. Existing project control processes are outlined along with multi-dimensional and 4D/5D visualization approaches. The review establishes the background and context for the research into improving project controls in the UK construction industry.

![76

Fig2: TPI Reporting Spreadsheet Sample

Source: Company C TPI reporting Excel Spreadsheet

Uniformity has been achieved in recent times within the TPI sheets;

however data is from a myriad of packages and inputted manually with no

set access rights.

4.2 Consultants

The role of the consultant, in the early stages, is to act on behalf of

Company C in the surveying, design, economics and „in confidence‟ works.

In general, consultants also have available MSP, however the general

consensus, even within some consultants, is that it is not used effectively

for progress monitoring and some of the consultants interviewed seemed to

have little knowledge of progress monitoring in this regard, however, other

consultants are very capable at progress monitoring, but due to „budgetary

constraints‟ they limit the monitoring.

Once there is a contractor allocated to the project, the role of the consultant

shifts to that of employer‟s agent; there is occasionally a change of

consultant at this stage, depending on CFADS group requirements. The

employer‟s agent is in a position to monitor the contractor as well as other

duties; there is, however, little confidence that this is done effectively on a

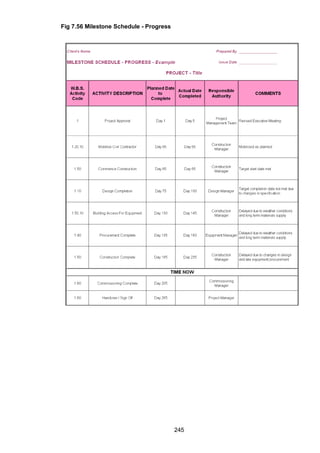

KEY PROJECT EVENTS

Points

Past

Achieved

inYear

Baseline

inYear

Achieved

inYear

Forecast

Future

Forecast

ACHIEVED

(MM/YY)

F/CAST

(MM/YY)

HA Commissioned/Project Commencement 1 Jun-03

Strategic Assessment Complete (LGC 0) 1

Consultant Selected and Briefed 1

Public Consultation options selected 1

Value Management Completed 1

Reports and Estimates Approved 1

Business Case Approved (OGC1) 1

Procurement Strategy Confirmed (OGC2) 1 Sep-03

Public Consultation Start 2

ECI Tenders Invited 1 01/07/03 Single

Tender Assessment Completed 1

Preferred Route Selected 3

DfT / Ministerial Approval 2

Preferred Route Announcement 2

Value Engineering Completed 4

Investment Decision Confirmed (OGC3) 2 Sep-03

ECI Contract Awarded 3 Aug-03

Preliminary Designs & Consultations completed 3

Reports and Estimates Approved 3

Stage 3 Assessment Report approved 3

Draft Orders and ES Published (OGC 3A) 5

End of Objection Period 3

PI Notice Issued 3

Public Inquiry Start 4

Post Inquiry Risk Assessment Completed 2

Imspector's Report Received 2

Secretary of State's Decision Announced 2

Orders Made 2

End of High Court Challenge Period 2

Works Price Reviewed/Confirmed (OGC3B) 2

Works Commitment Approval 2

Notices to Treat and Enter Served 1

Land Entry Secures 1

Start of Works 1 Oct-03

Road Opened 26 Dec-04

Business Confirms Readiness for Service (OGC4) 1 Spring-05

Handed into Maintenance 1

Noise Appeals Completed 1

First Pt 1 Claims Notice Published 1

Maintenance Certificate Issued 1

Benefits Evaluation Review Complete (OGC5) 0

Financially Closed 0

PROGRESS 100 0 0 0 0 0

AGREED

TARGET

FORECAST

Start of Year (Achieved in preceeding Year)

Current Position

End of Year (March)

TOTAL N/A N/A

IN-YEAR BUDGET CONTROL (excluding Land)

In-Year Budget (Fixed for Year) - [C]

Last Month's FYF - [D]

This Month's FYF - [E]

In-Month Variance - [E-D]

Variance to Budget - [C-E]

TOTAL PROJECT EXPENDITURE (excluding Land)

Historical Spend (post Apr 01/TPI entry)

In- Year Spend

Future Years Spend

TOTAL

30.500

26.863

28.862

1.999

53.020

AMOUNT £m

18.617

5.541

28.862

1.638

AMOUNT £m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/112675-150805074221-lva1-app6891/85/Project-highlights-88-320.jpg)