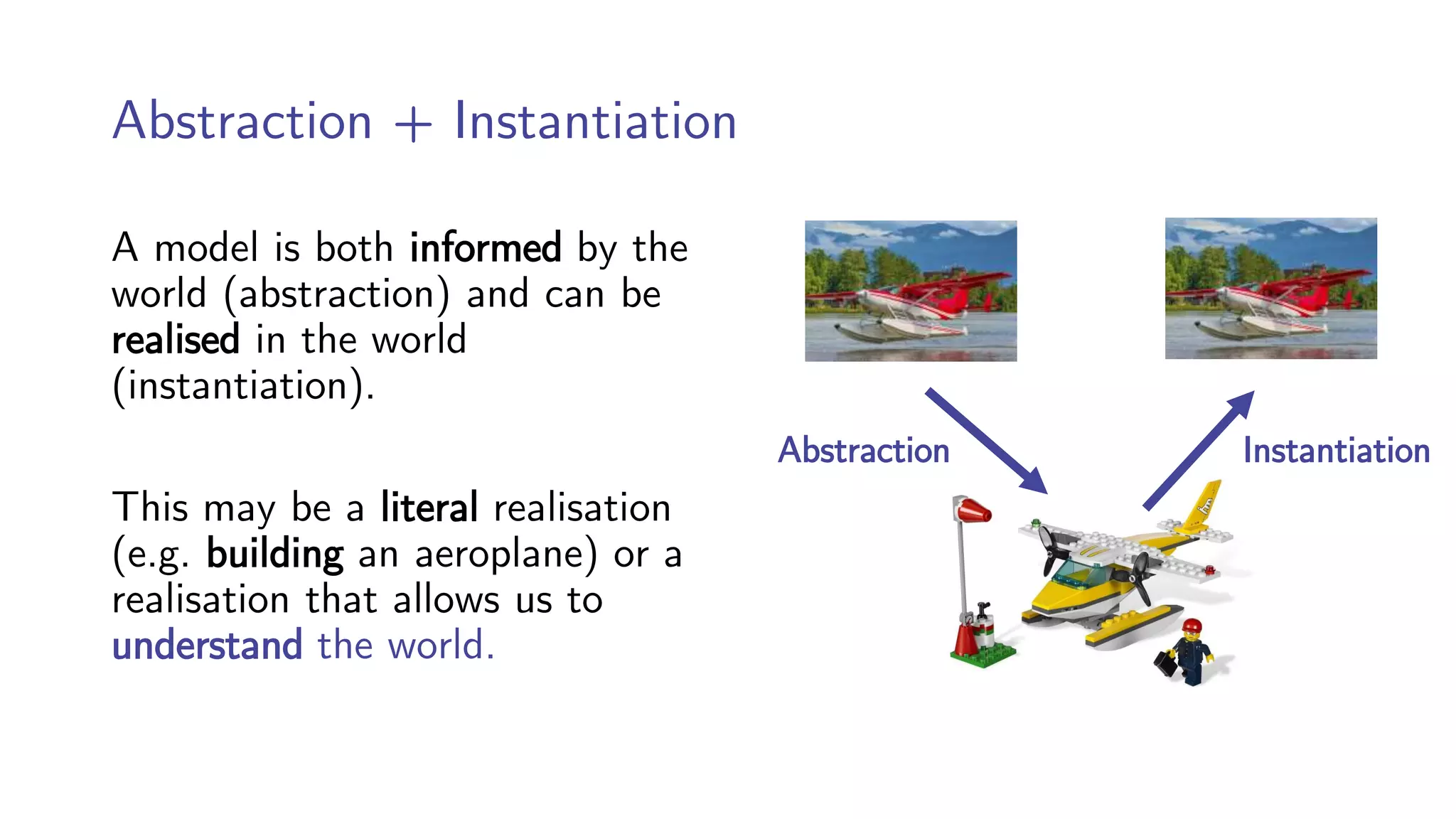

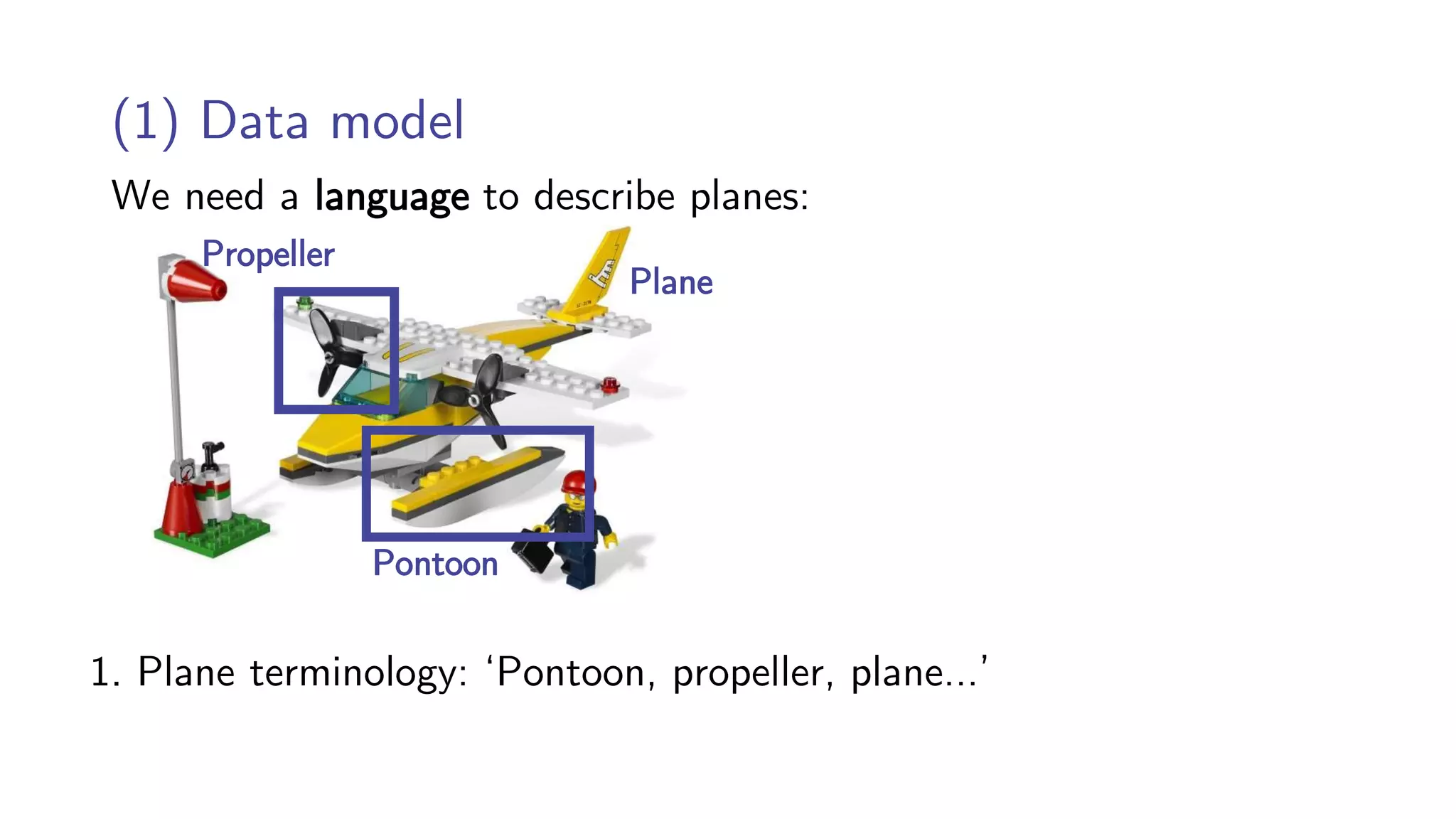

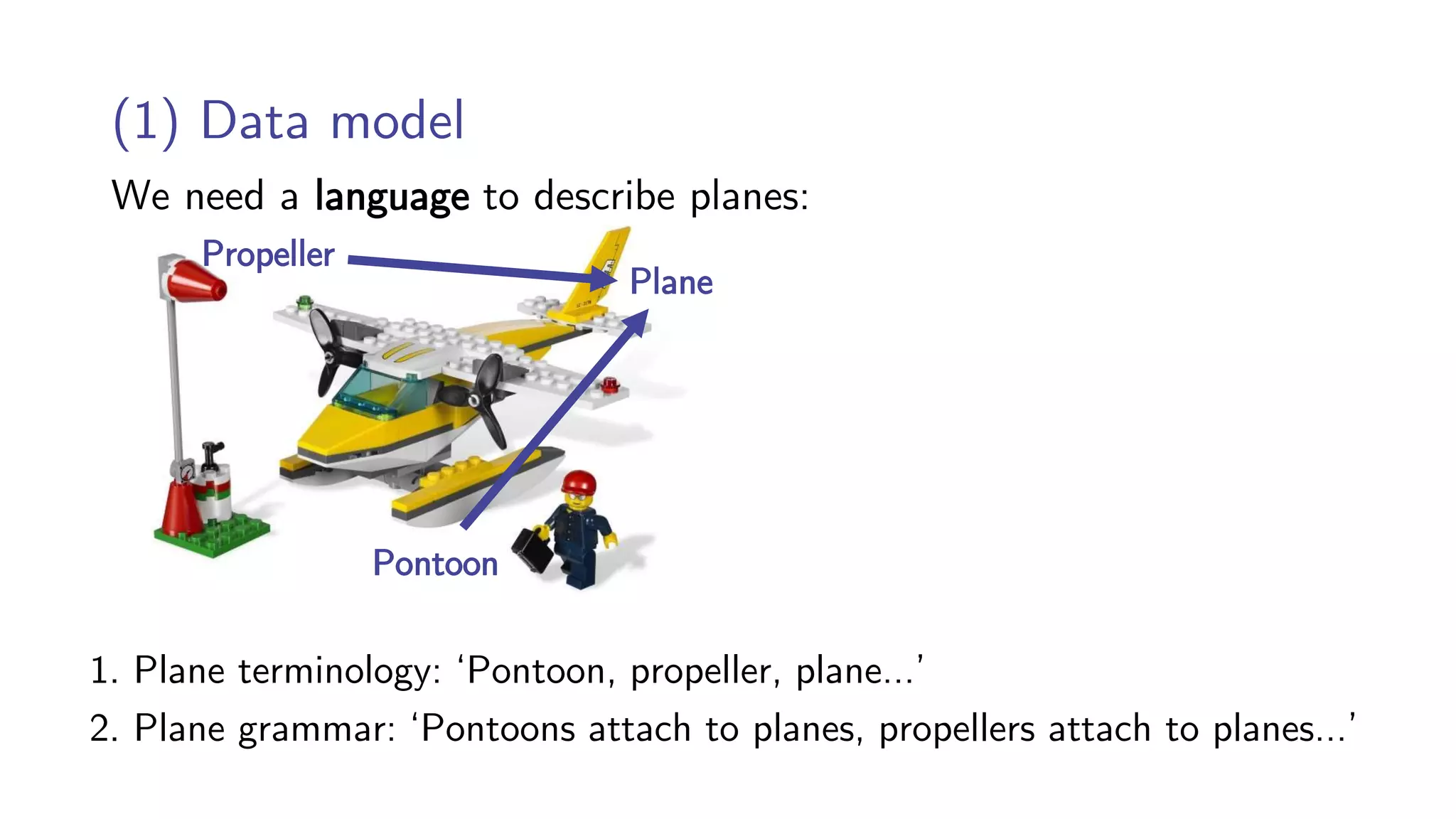

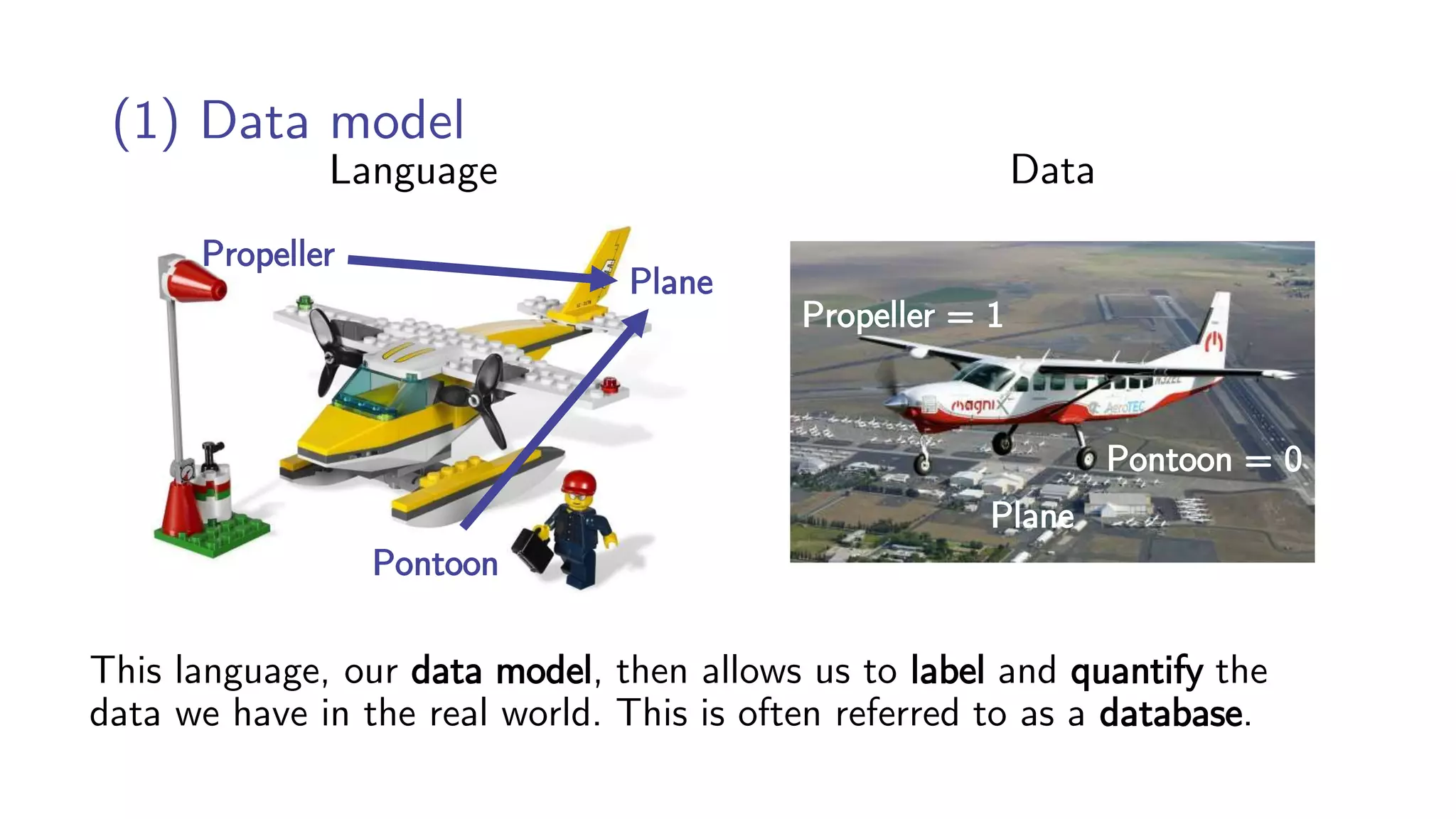

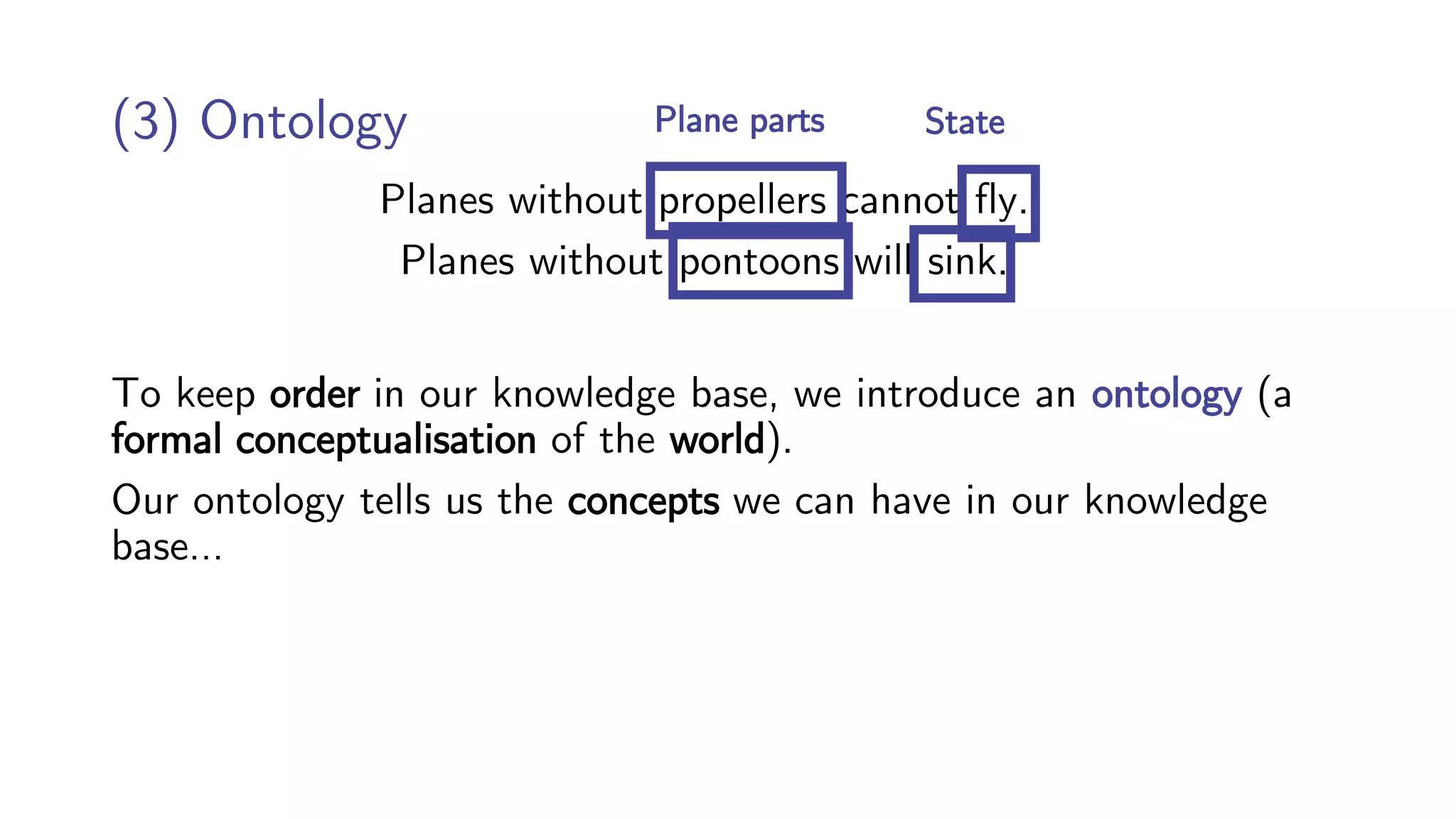

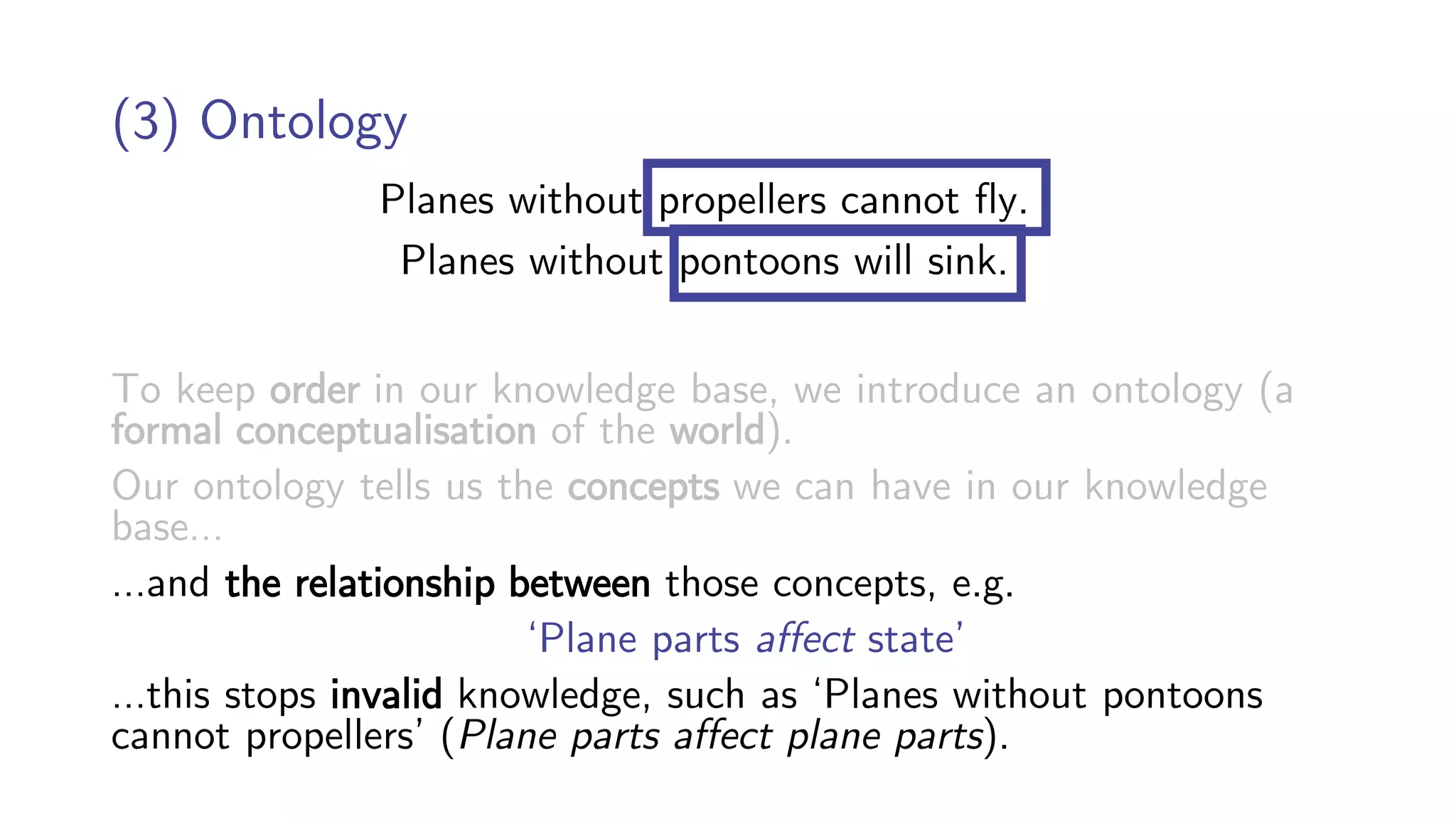

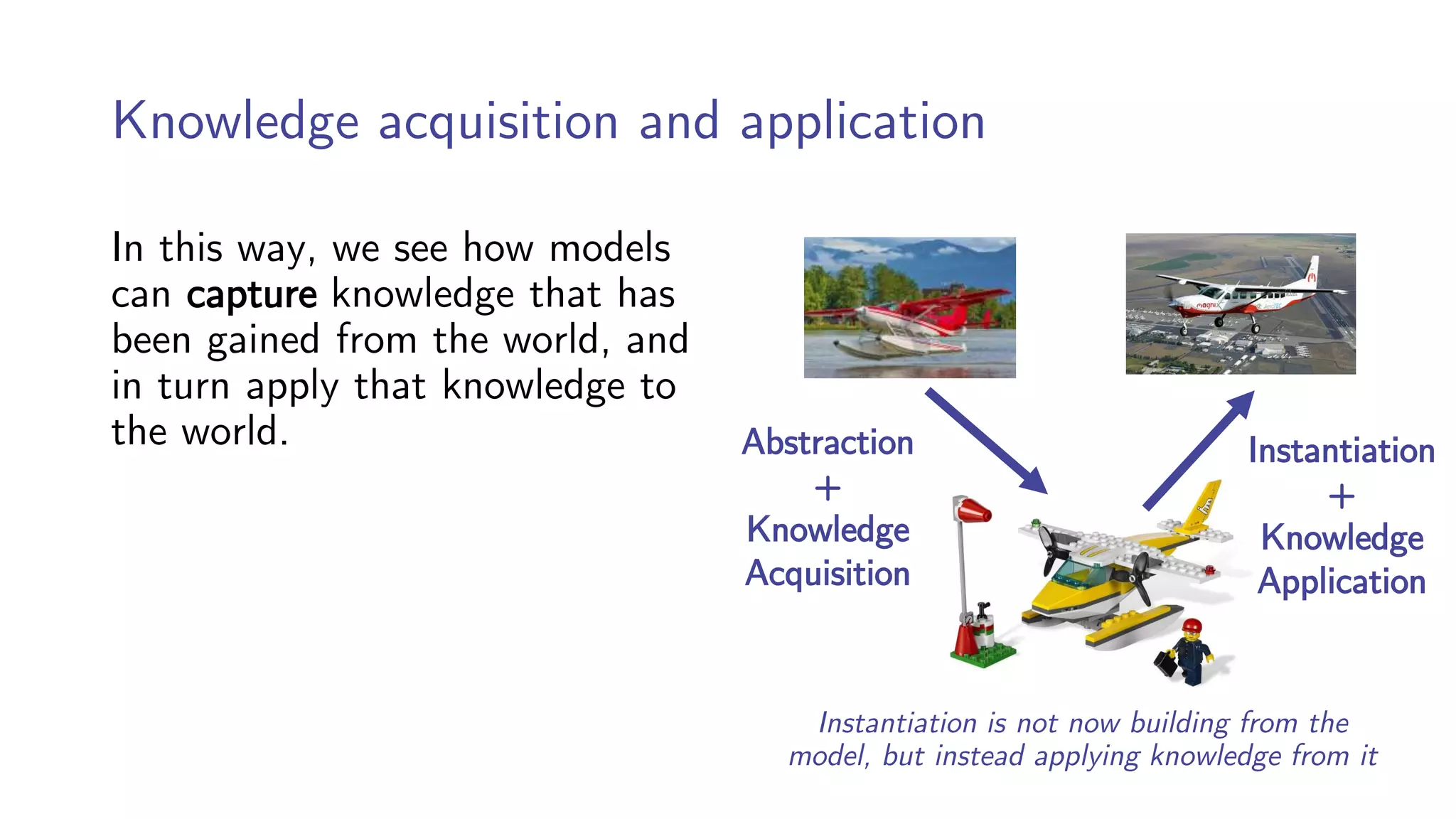

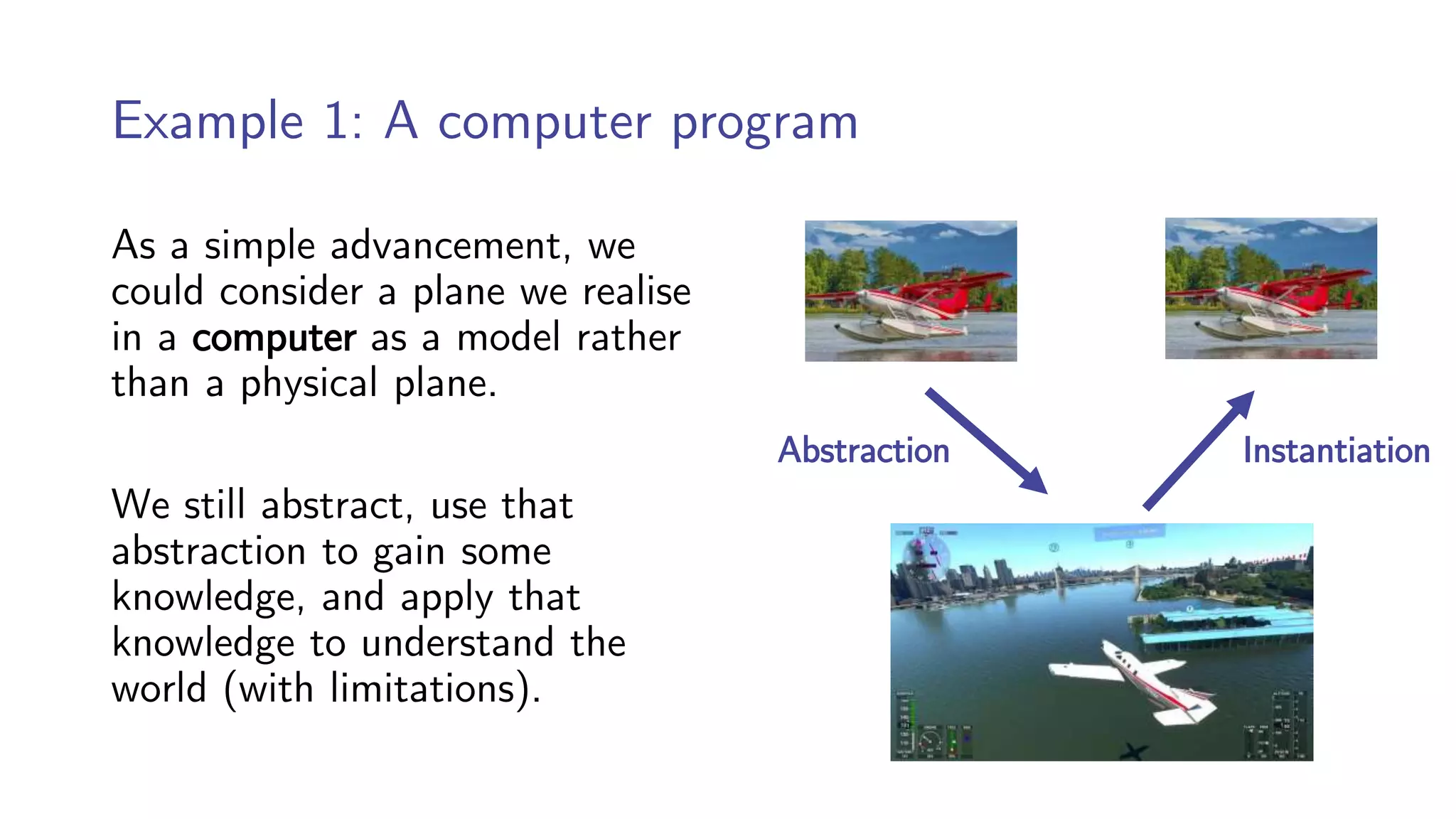

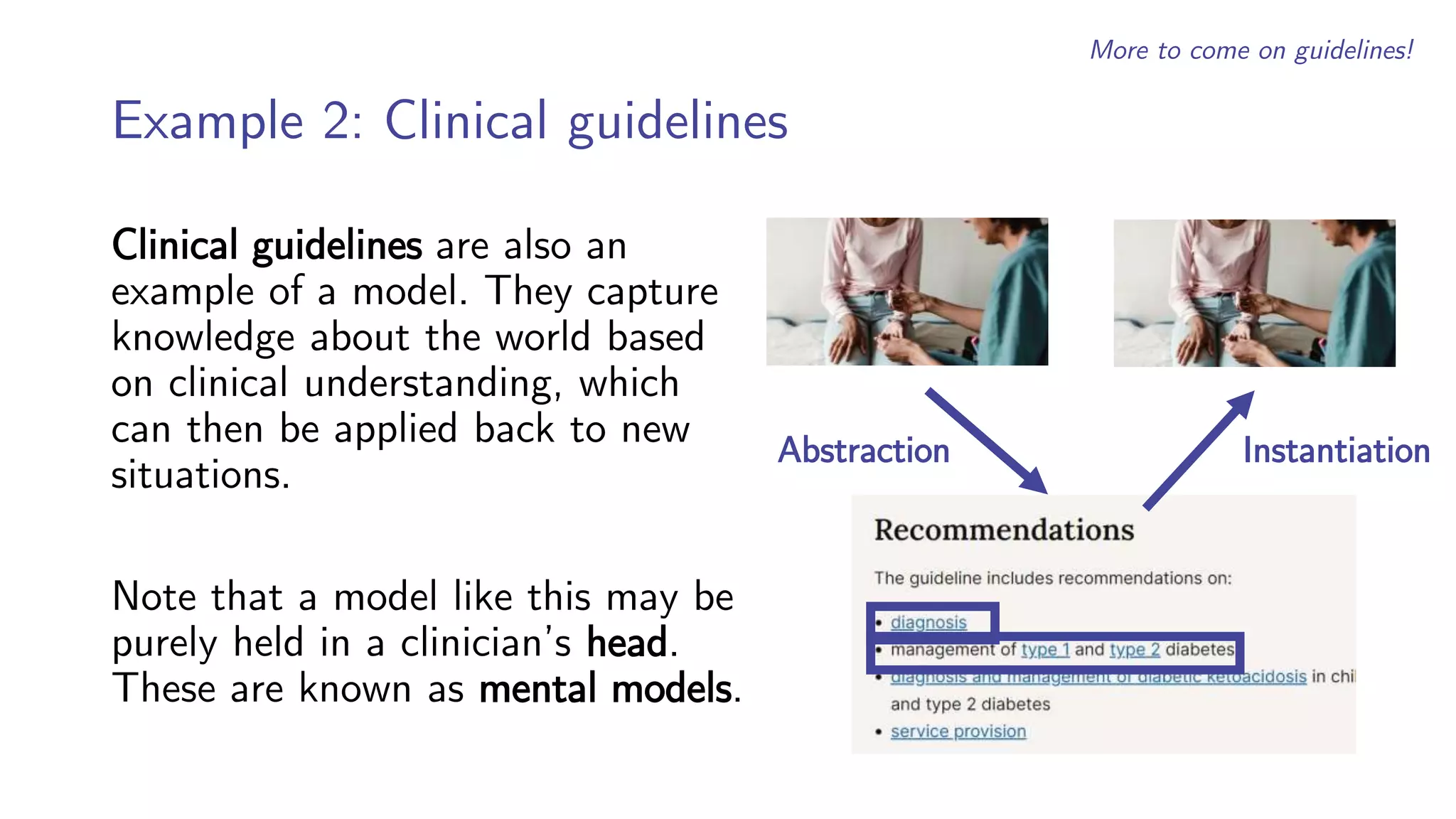

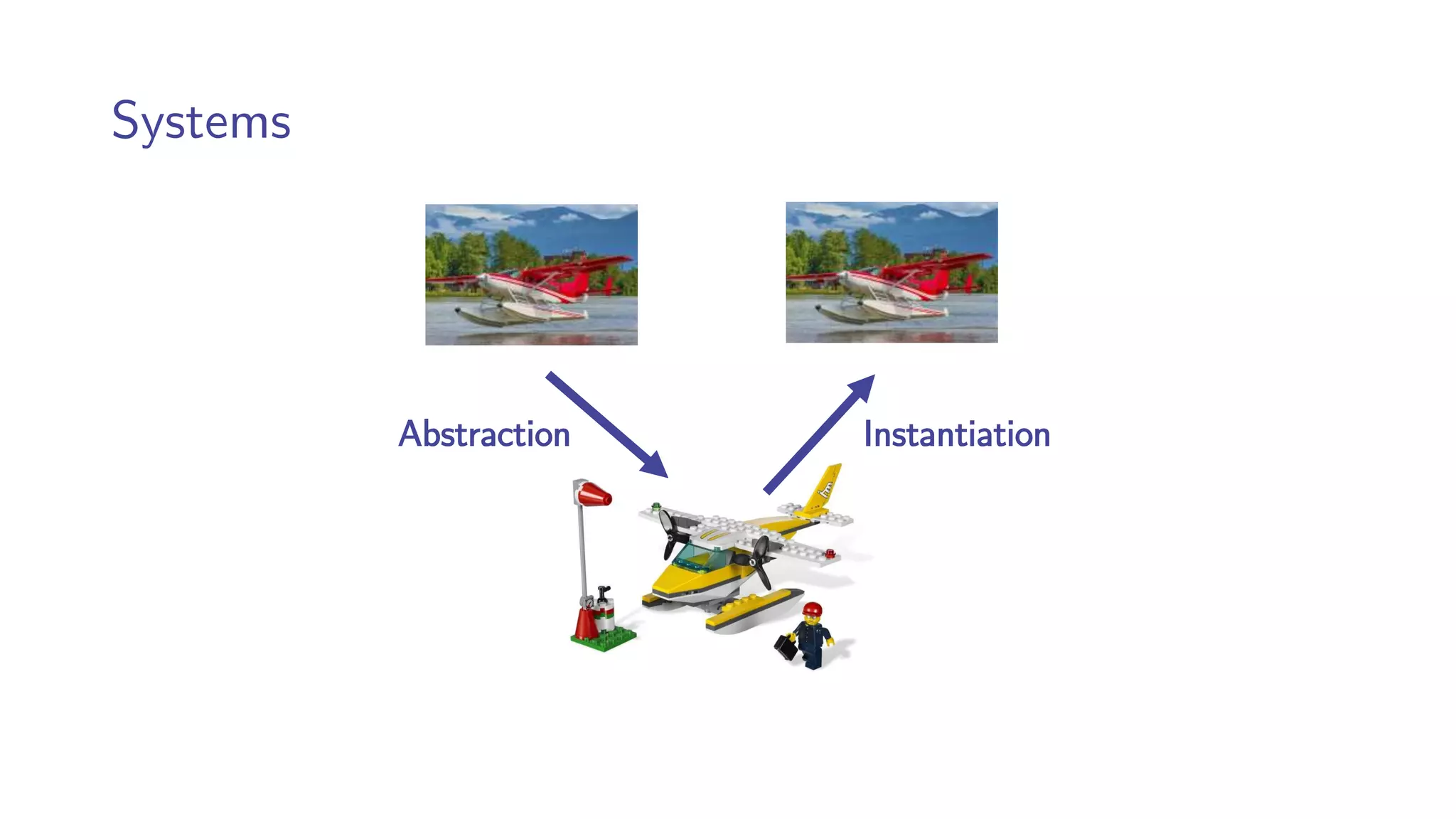

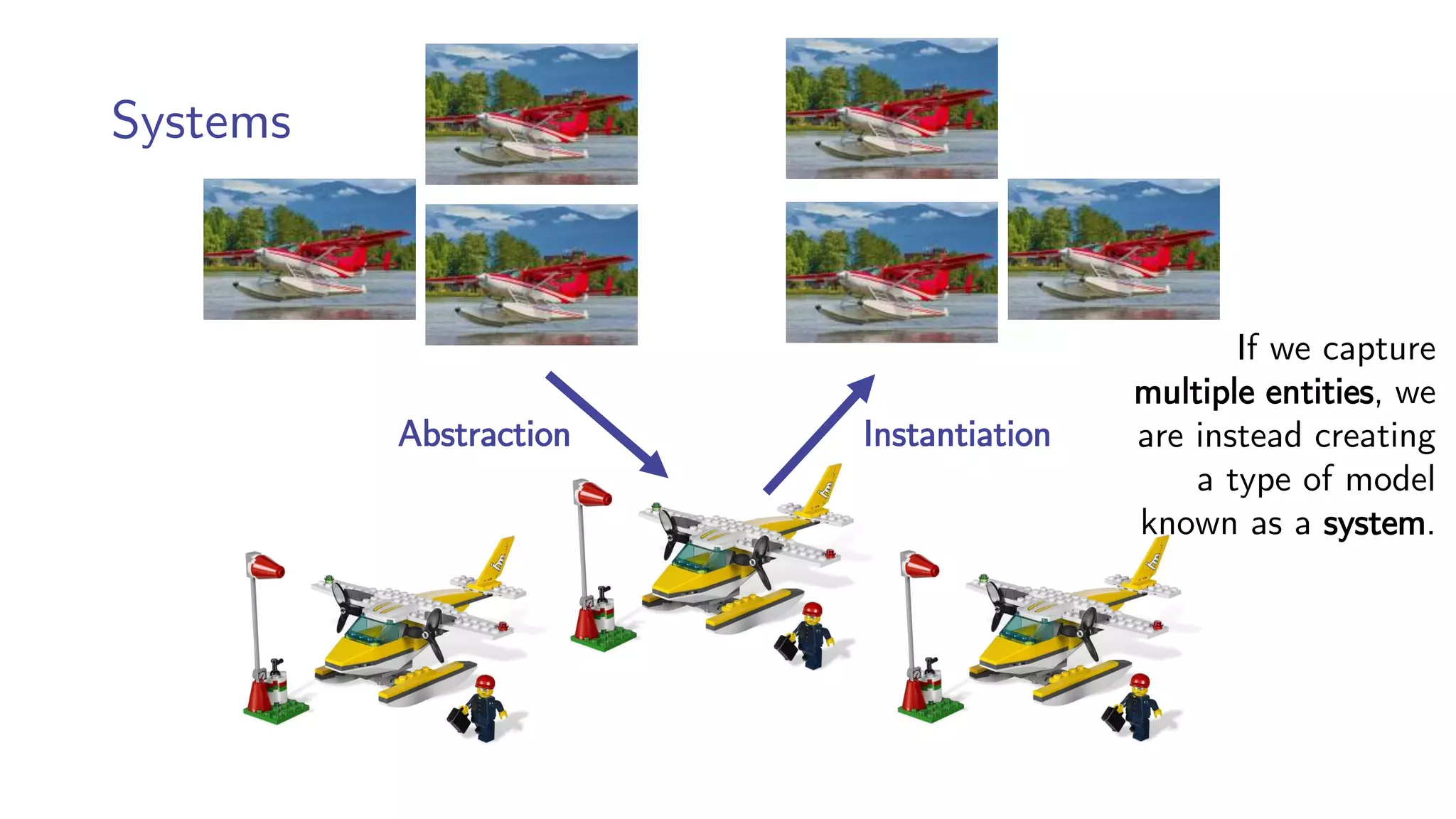

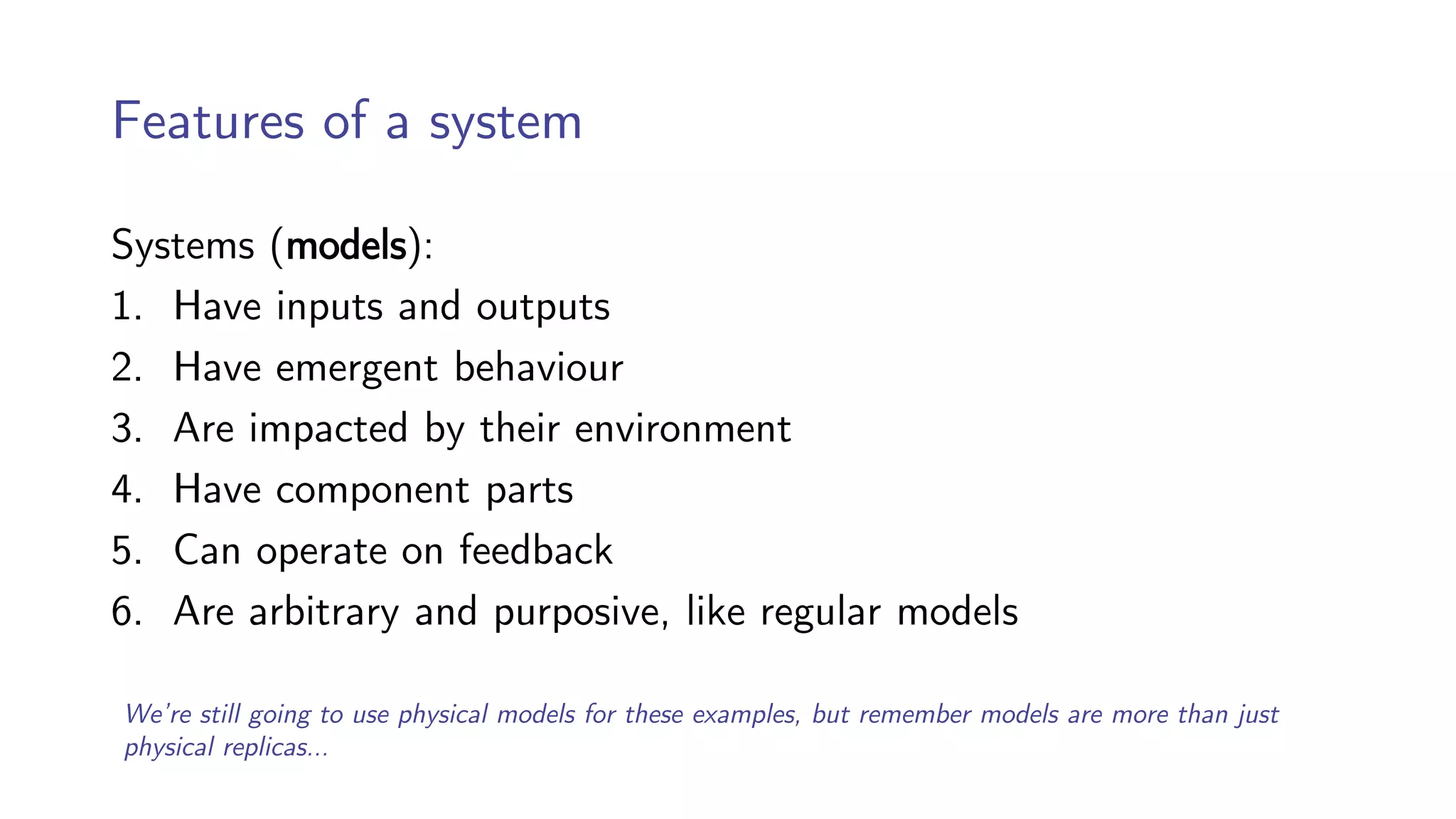

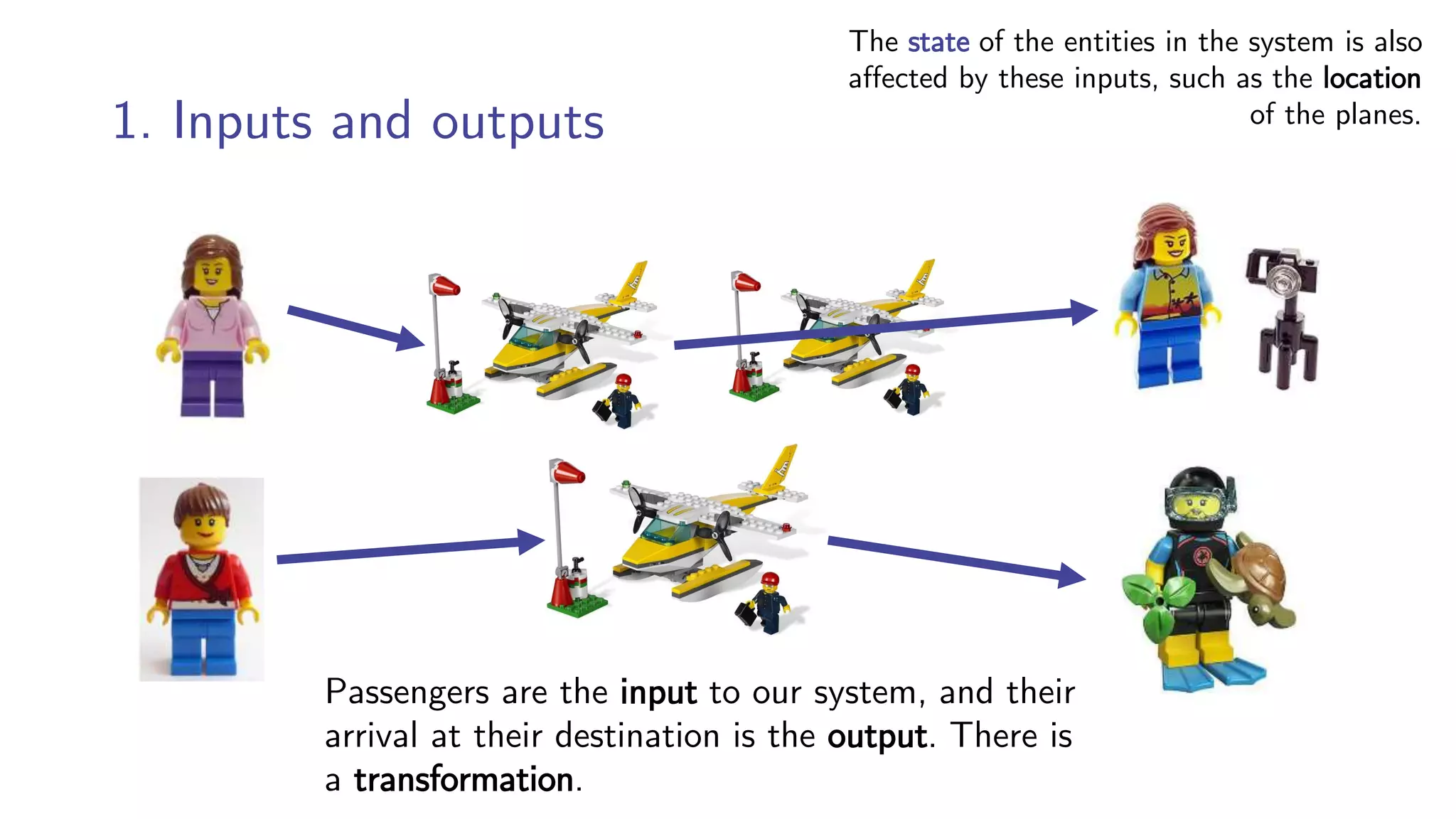

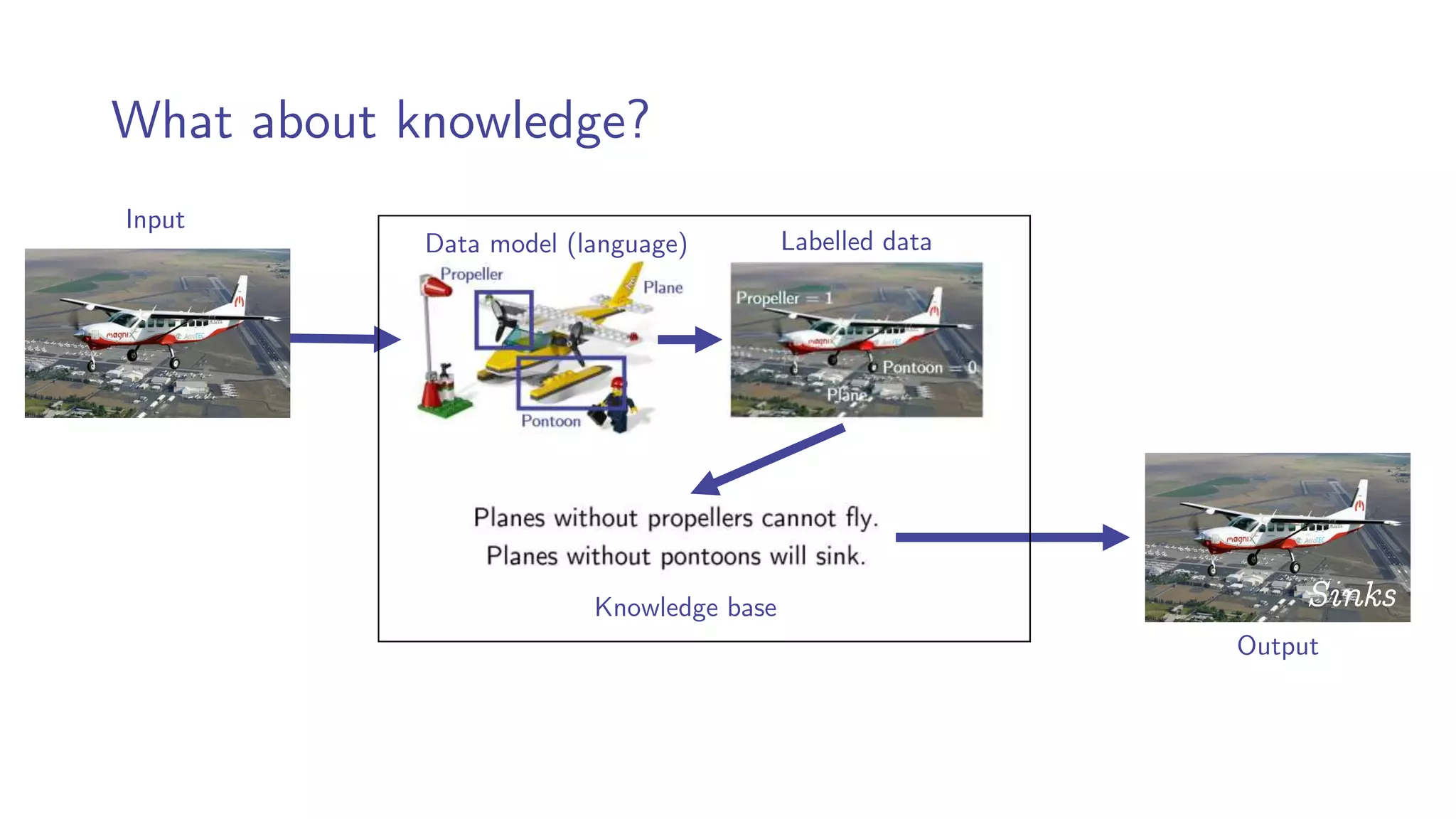

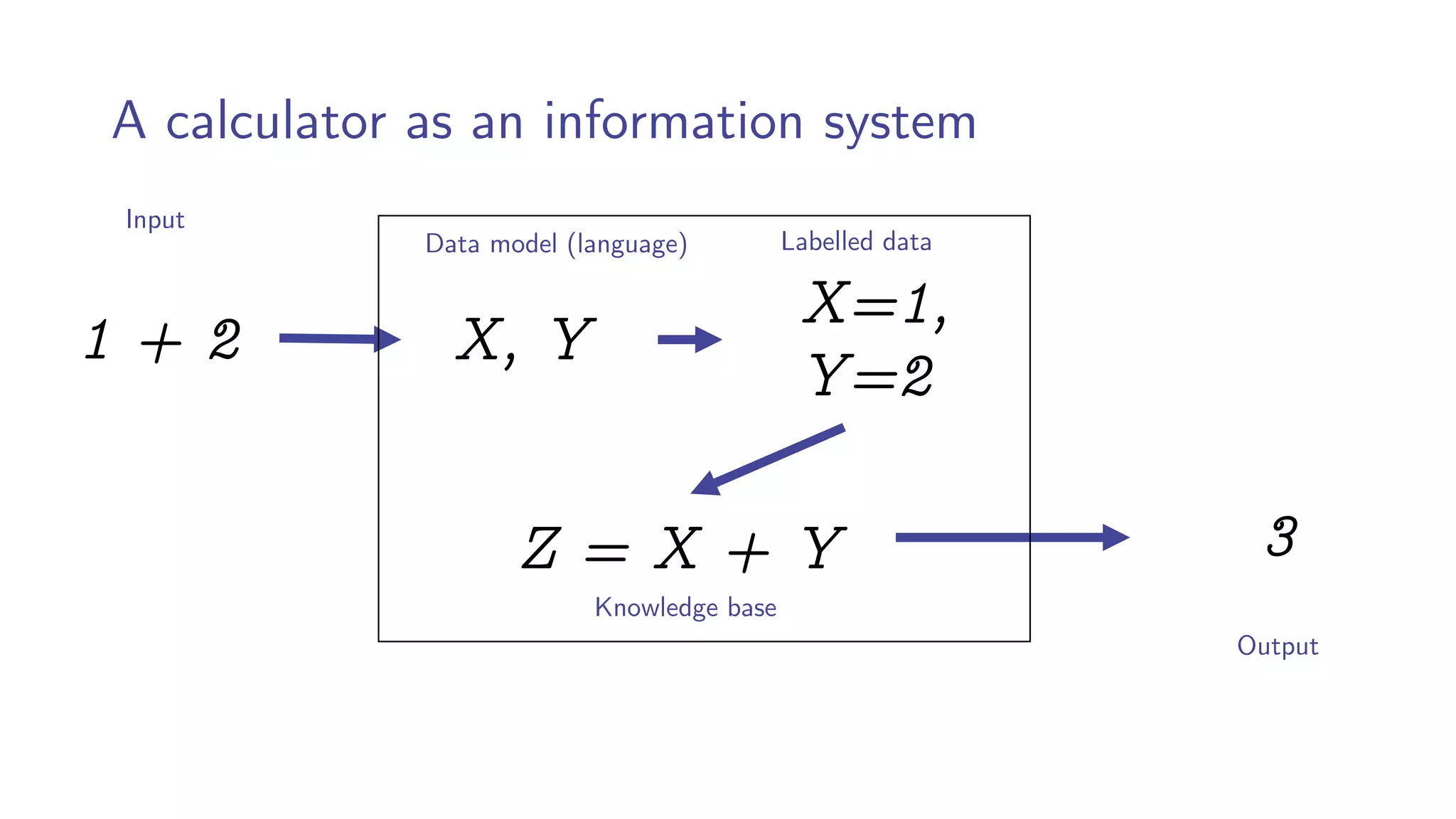

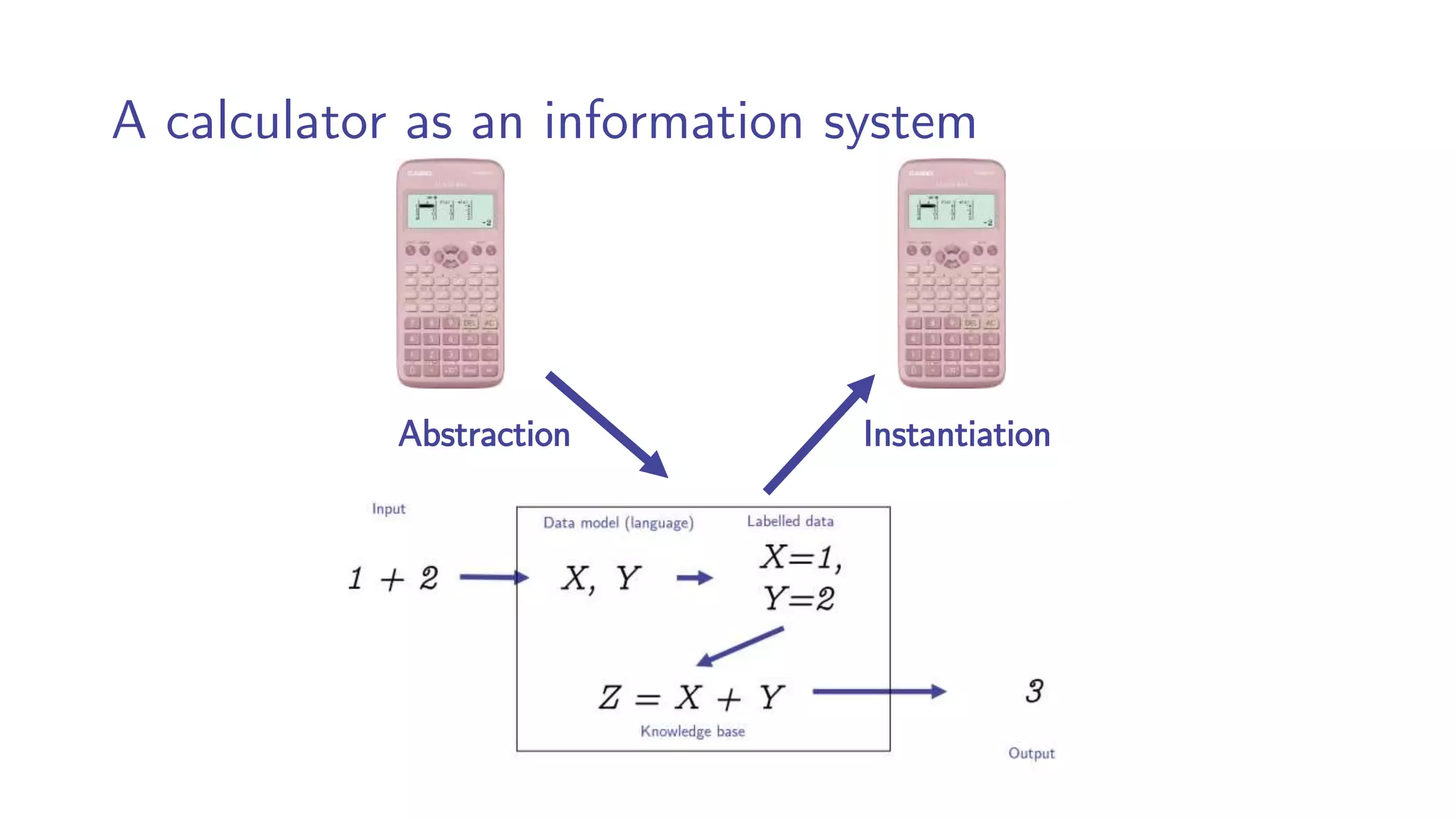

The lecture explores fundamental concepts in health informatics, emphasizing the roles of models, information, and information systems. It discusses how models serve as representations of reality tailored for specific purposes, aiding in understanding and diagnosing patient conditions. Furthermore, it outlines the structure and implications of systems, particularly information systems, in transforming data into actionable knowledge for clinical interventions.