This document provides an overview and table of contents for the textbook "Principles of Economics" by Dirk Mateer and Lee Coppock. It was published by W.W. Norton & Company, which has been independently owned by its employees since the 1950s. The textbook covers microeconomic and macroeconomic concepts across 33 chapters organized into 10 parts. It includes examples, graphs, and discussions of economic principles and how they apply to real-world situations and current events. The authors provide brief biographies dedicating the book to their fathers for encouraging them in teaching economics.

![Reinforcers

Practice What You Know boxes are in-

chapter exercises that allow students

to self-assess while reading and provide

a bit more hand-holding than usual.

While other books have in-chapter ques-

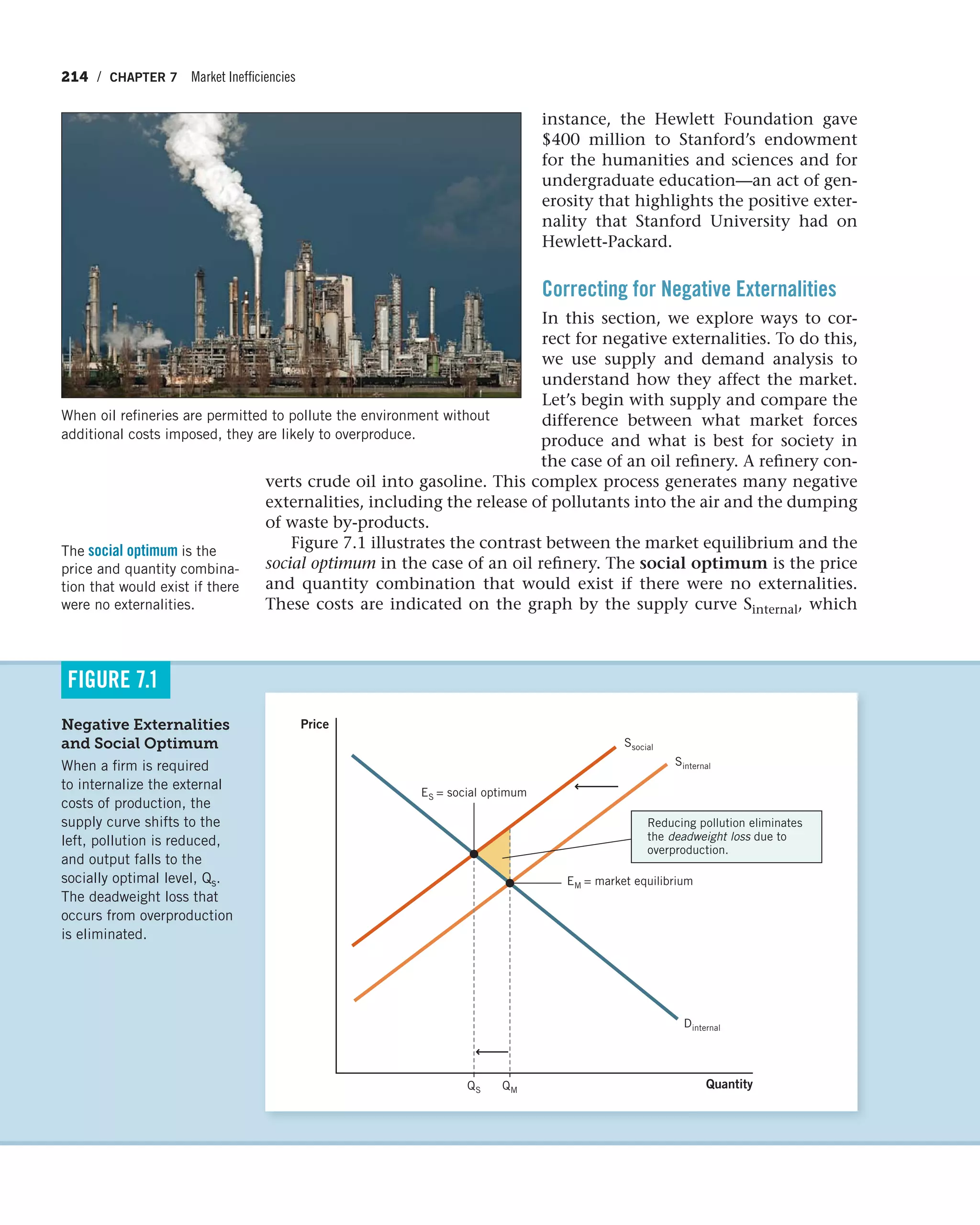

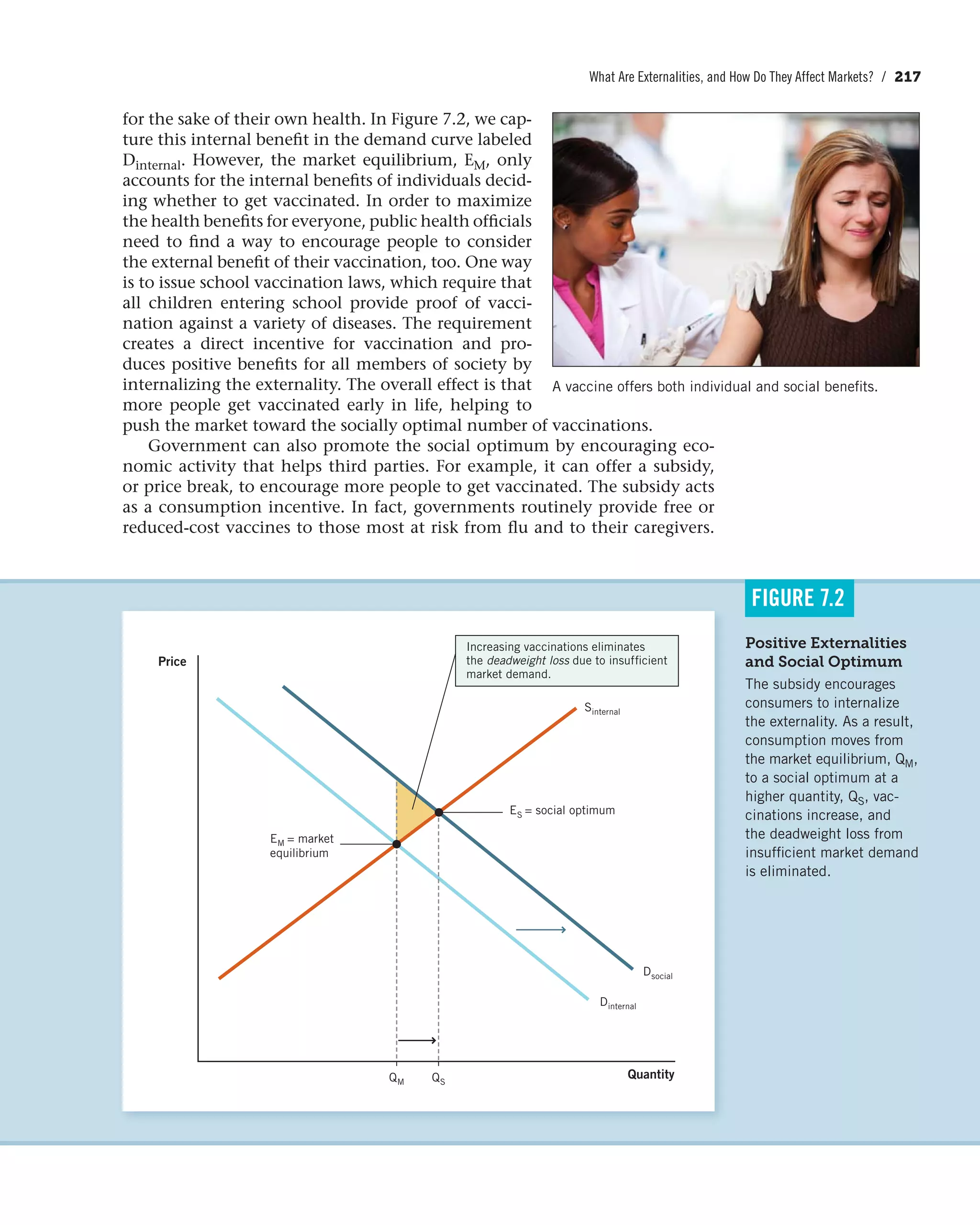

tions, no other book consistently frames

these exercises within real-world situa-

tions that students relate to.

Income Elasticity

Question: A college student eats ramen noodles twice

a week and earns $300/week working part-time. After

graduating, the student earns $1,000/week and eats

ramen noodles every other week. What is the student’s

income elasticity?

Answer: The income elasticity of demand using the midpoint method is

EI =

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(I2 - I1) , [(I1 + I2) , 2]

Plugging in yields

EI =

(0.5 - 2.0) , [(2.0 + 0.5) , 2]

($1000 - $300) , [($300 + $1000) , 2]

Simplifying yields

EI =

-1.5 , 1.25

$700 , $650

Therefore, EI = -1.1.

The income elasticity of demand is positive for normal goods and negative

for inferior goods. Therefore, the negative coefficient indicates that ramen noo-

dles are an inferior good over the range of income—in this example, between

$300 and $1,000. This result should confirm your intuition. The higher post-

graduation income enables the student to substitute away from ramen noodles

and toward other meals that provide more nourishment and enjoyment.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Yummy, or all you can afford?

d

2

2

-

EI

ma

e

h

st

v

AAnswer The income elasticity ofAnswer: The income elasticity of

EI =

(Q2

(I

Plugging in yields

EI =

(0.5

($1000 -

Simplifying yields

E

Therefore, EI = -1.1.

The income elasticity of dem

for inferior goods. Therefore, the

dles are an inferior good over the

$300 and $1,000. This result sh

graduation income enables the s

and toward other meals that prov

Suppose that a local pizza place likes to run a “late-night special” after

11 p.m. The owners have contacted you for some advice. One of the owners

tells you, “We want to increase the demand for our pizza.” He proposes two

marketing ideas to accomplish this:

1. Reduce the price of large pizzas.

2. Reduce the price of a complementary good—for example, offer two half-

priced bottles or cans of soda with every large pizza ordered.

Question: What will you recommend?

Answer: First, consider why “late-night specials” exist in the first place. Since

most people prefer to eat dinner early in the evening, the store has to encour-

age late-night patrons to buy pizzas by stimulating demand. “Specials” of all

sorts are used during periods of low demand when regular prices would leave

the establishment largely empty.

Next, look at what the question asks. The owners want to know which

option would “increase demand” more. The question is very specific; it is

looking for something that will increase (or shift) demand.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Cheap pizza or . . . . . . cheap drinks?

D1

Price

(dollars

per pizza)

Quantity (pizza)

A reduction in the

price of pizza causes

a movement along the

demand curve.

Shift or Slide?

(CONTINUED)

Preface / xxxvii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-39-2048.jpg)

![8 / CHAPTER 1 The Five Foundations of Economics

Positive and Negative Incentives

Positive incentives are those that encourage action. For example, end-of-the-

year bonuses motivate employees to work hard throughout the year, higher oil

prices cause suppliers to extract more oil, and tax rebates encourage citizens to

spend more money. Negative incentives also encourage action. For instance,

the fear of receiving a speeding ticket keeps motorists from driving too fast, and

the dread of a trip to the dentist motivates people to brush their teeth regularly.

In each case, a potential negative consequence spurs individuals to action.

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics:

The Big Picture

Identify whether each of the following state-

ments identifies a microeconomic or a macro-

economic issue.

The national savings rate is less than 2% of

disposable income.

Answer: The national savings rate is a

statistic based on the average amount

each household saves as a percentage of

income. As such, this is a broad measure

of savings and something that describes a

macroeconomic issue.

Jim was laid off from his last job and is currently

unemployed.

Answer: Jim’s personal financial circumstances constitute a microeconomic

issue.

Apple decides to open up 100 new stores.

Answer: Even though Apple is a very large corporation and 100 new stores will

create many new jobs, Apple’s decision is a microeconomic issue because

the basis for its decision is best understood as part of the firm’s competitive

strategy.

The government passes a jobs bill designed to stabilize the economy during a recession.

Answer: You might be tempted to ask how many jobs are created before

deciding, but that is not relevant to this question. The key part of the

statement refers to “stabiliz[ing] the economy during a recession.” This is an

example of a fiscal policy, in which the government takes an active role in

managing the economy. Therefore, it is a macroeconomic issue.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

This mosaic of the flag illustrates the difference between micro and

macro.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-62-2048.jpg)

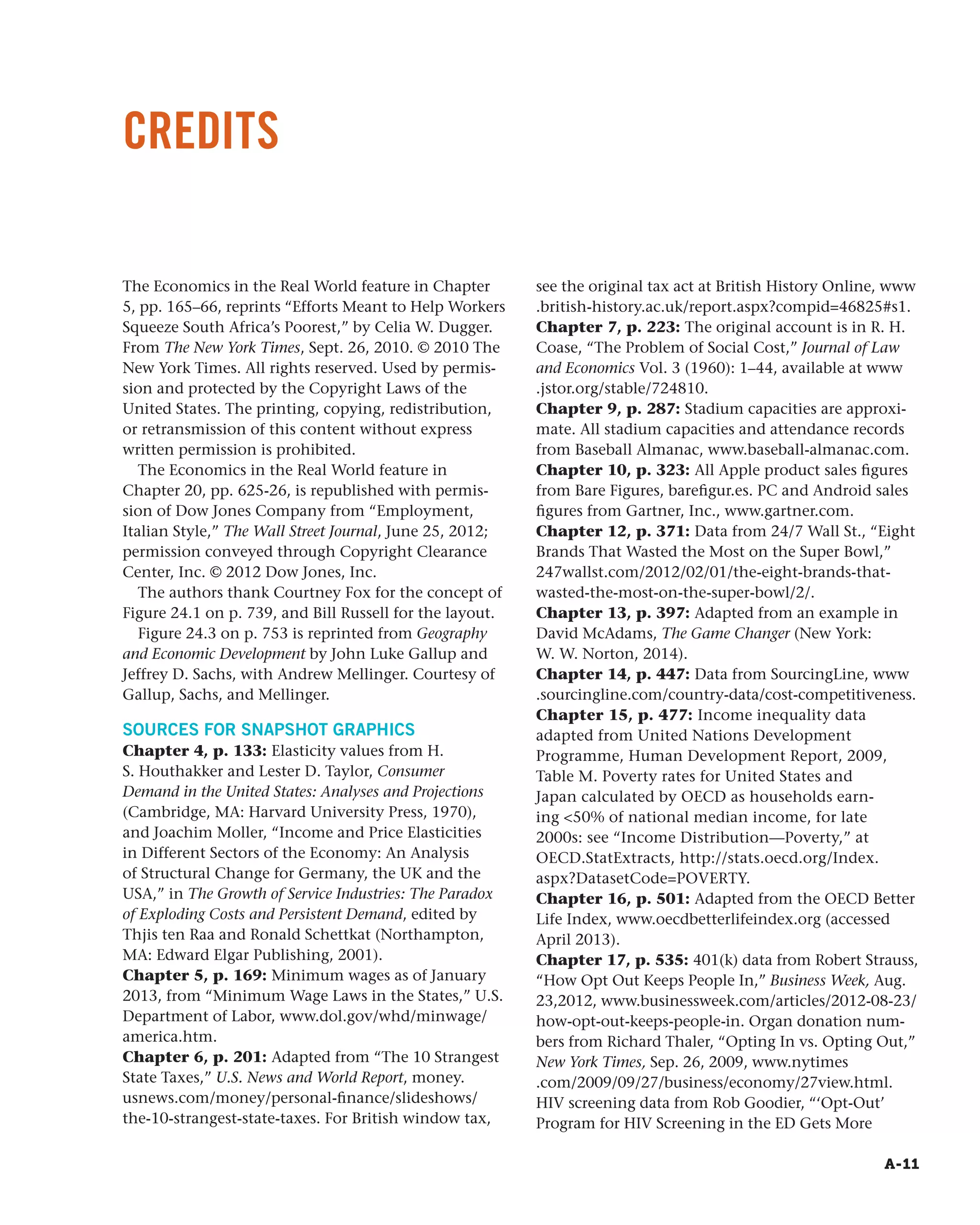

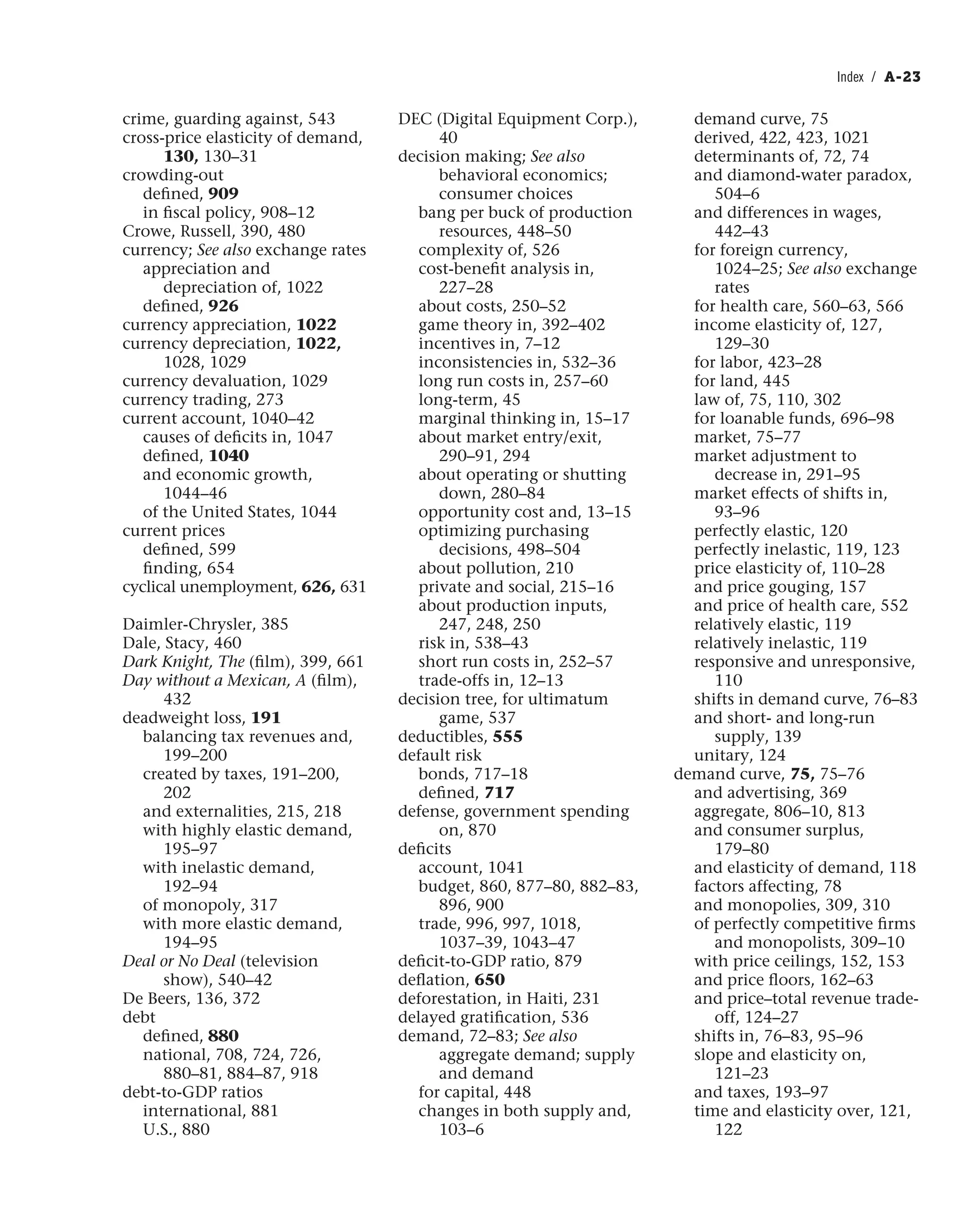

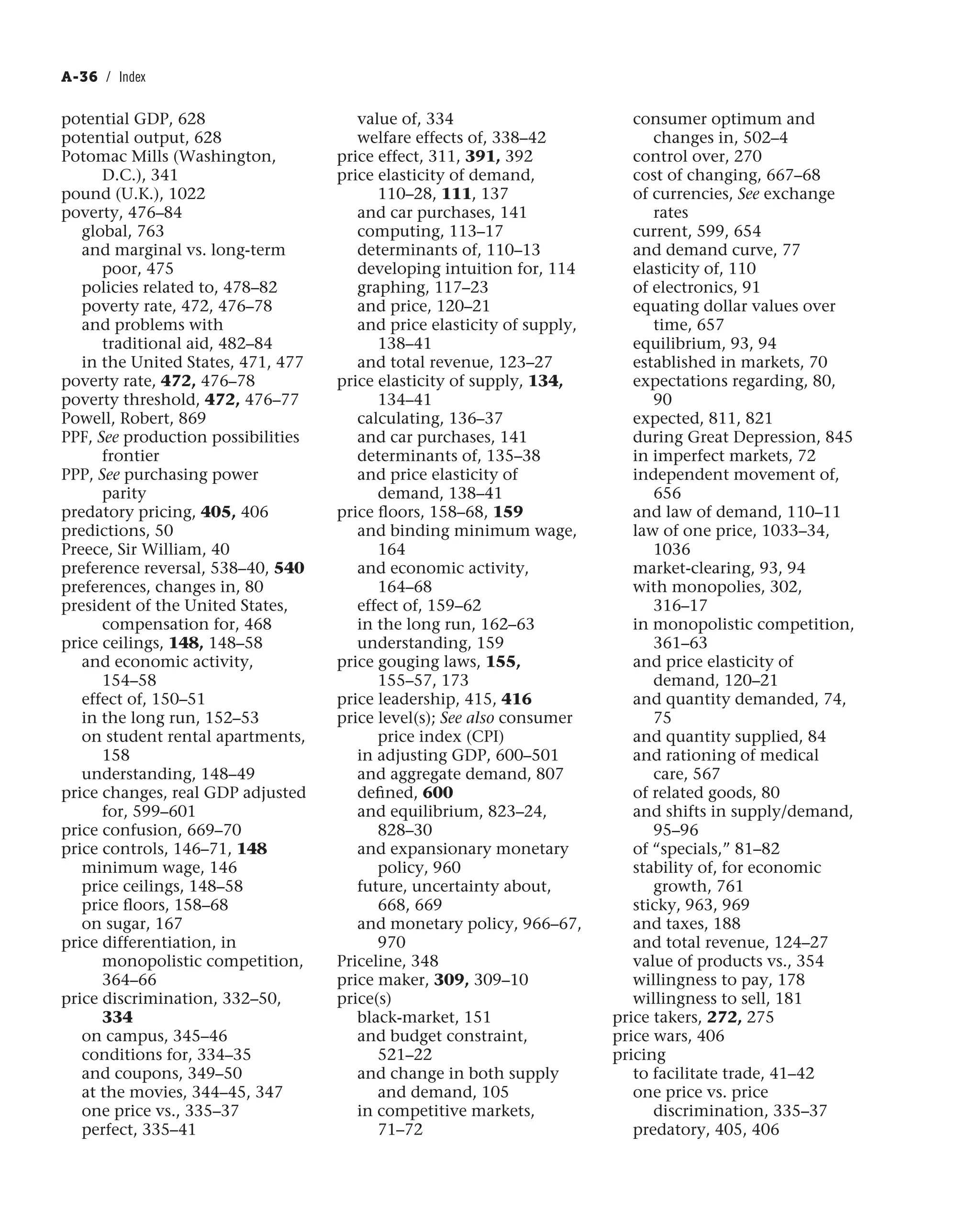

![116 / CHAPTER 4 Elasticity

The Midpoint Method

The calculation above was simple because we looked at the change in price

and the change in the quantity demanded from only one direction—that is,

from a high price to a lower price. However, the complete—and proper—way

to calculate elasticity is from both directions. Consider the following demand

schedule (it doesn’t matter what the product is):

Price Quantity demanded

$12 20

$ 6 30

Let’s calculate the elasticity of demand. If the price drops from $12 to

$6—a drop of 50%—the quantity demanded increases from 20 to 30—a rise

of 50%. Plugging the percentage changes into ED yields

Price Elasticity of Demand = ED =

50%

-50%

= -1.0

But if the price rises from $6 to $12—an increase of 100%—the quantity

demanded falls from 30 to 20, or decreases by 33%. Plugging the percentage

changes into ED yields

Price Elasticity of Demand = ED =

-33%

100%

= -0.33

This result occurs because percentage changes are usually calculated by using

the initial value as the base, or reference point. In this example, we worked the

problem two ways: by using $12 as the starting point and dropping the price

to $6, and by using $6 as the starting point and increasing the price to $12.

Even though we are measuring elasticity over the same range of values, the

percentage changes are different.

To avoid this problem, economists use the midpoint method, which gives

the same answer for the elasticity no matter what point you begin with. Equa-

tion 4.2 uses the midpoint method to express the price elasticity of demand.

While this equation looks more complicated than Equation 4.1, it is not. The

midpoint method merely specifies how to plug in the initial and ending val-

ues for price and the quantity to determine the percentage changes. Q1 and

P1 are the initial values, and Q2 and P2 are the ending values.

ED =

change in Q , average value of Q

change in P , average value of P

=

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(P2 - P1) , [(P1 + P2) , 2]

The change in the quantity demanded, (Q2 - Q1), and the change in price,

(P2 - P1), are each divided by the average of the initial and ending values, or

[(Q1 + Q2) , 2] and [(P1 + P2) , 2], to provide a way of calculating elasticity.

(Equation 4.2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-170-2048.jpg)

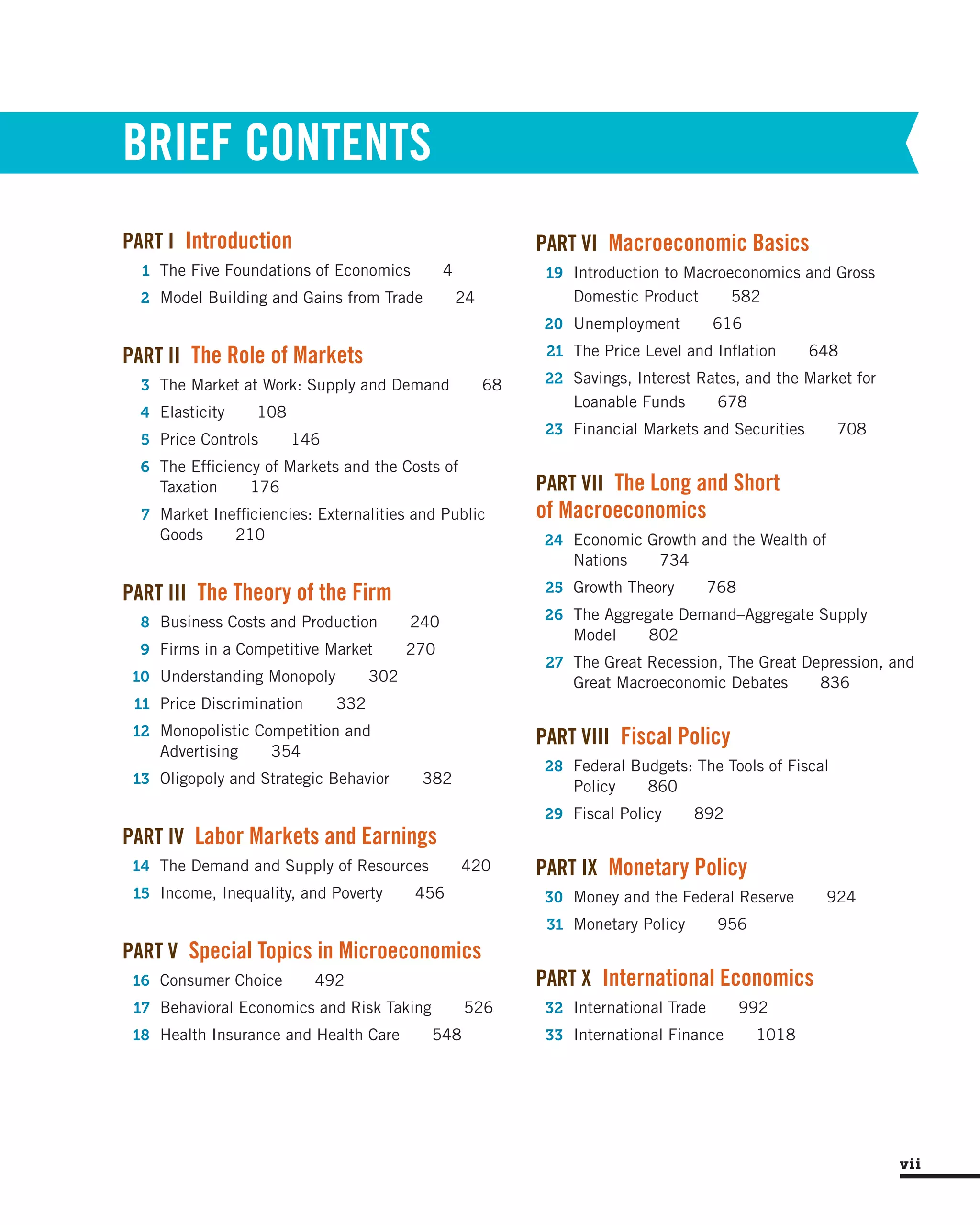

![What Is the Price Elasticity of Demand, and What Are Its Determinants? / 117

The midpoint method is the preferred method for solving elasticity prob-

lems. To see why this is the case, let’s return to our pizza demand example.

If the price rises from $6 to $12, the quantity demanded falls from 30

to 20. Here the initial values are P1 = $6 and Q1 = 30. The ending values are

P2 = $12 and Q2 = 20. Using the midpoint method:

ED =

(20 - 30) , [(30 + 20) , 2]

($12 - $6) , [($12 + $6) , 2]

=

-10 , 25

$6 , $9

= -0.58

If the price falls from $12 to $6, quantity rises from 20 to 30. This time, the

initial values are P1 = $12 and Q1 = 20. The ending values are P2 = $6 and

Q2 = 30. Using the midpoint method:

ED =

(30 - 20) , [(20 + 30) , 2]

($6 - $12) , [($6 + $12) , 2]

=

10 , 25

-$6 , $9

= -0.58

When we calculated the price elasticity of demand from $6 to $12 using $6

as the initial point, ED = -0.33. Moving in the opposite direction, from $12

to $6, made $12 the initial reference point and ED = -1.0. The midpoint

method shown above splits the difference and uses $9 and 25 pizzas as

the midpoints. This approach makes the calculation of the elasticity coeffi-

cient the same, -0.58, no matter what direction the price moves. Therefore,

economists use the midpoint method to standardize the results. So, using

the midpoint method, we arrived at an elasticity coefficient of -0.58, which

is between 0 and -1. What does that mean? In this case, the percentage

change in the quantity demanded is less than the percentage change in

the price. Whenever the percentage change in the quantity demanded is

smaller than the percentage change in price, we say that demand is inelas-

tic. In other words, the price drop does not make a big difference in how

much pizza consumers purchased from the pizza shop. When the elasticity

coefficient is less than -1, the opposite is true, and we say that demand is

elastic.

Graphing the Price Elasticity of Demand

Visualizing elasticity graphically helps us understand the relationship

between elastic and inelastic demand. Figure 4.1 shows elasticity graph-

ically. As demand becomes increasingly elastic, or responsive to price

changes, the demand curve flattens.

Figure 4.1a depicts the price elasticity for pet care. Many pet own-

ers report that they would pay any amount of money to help their sick

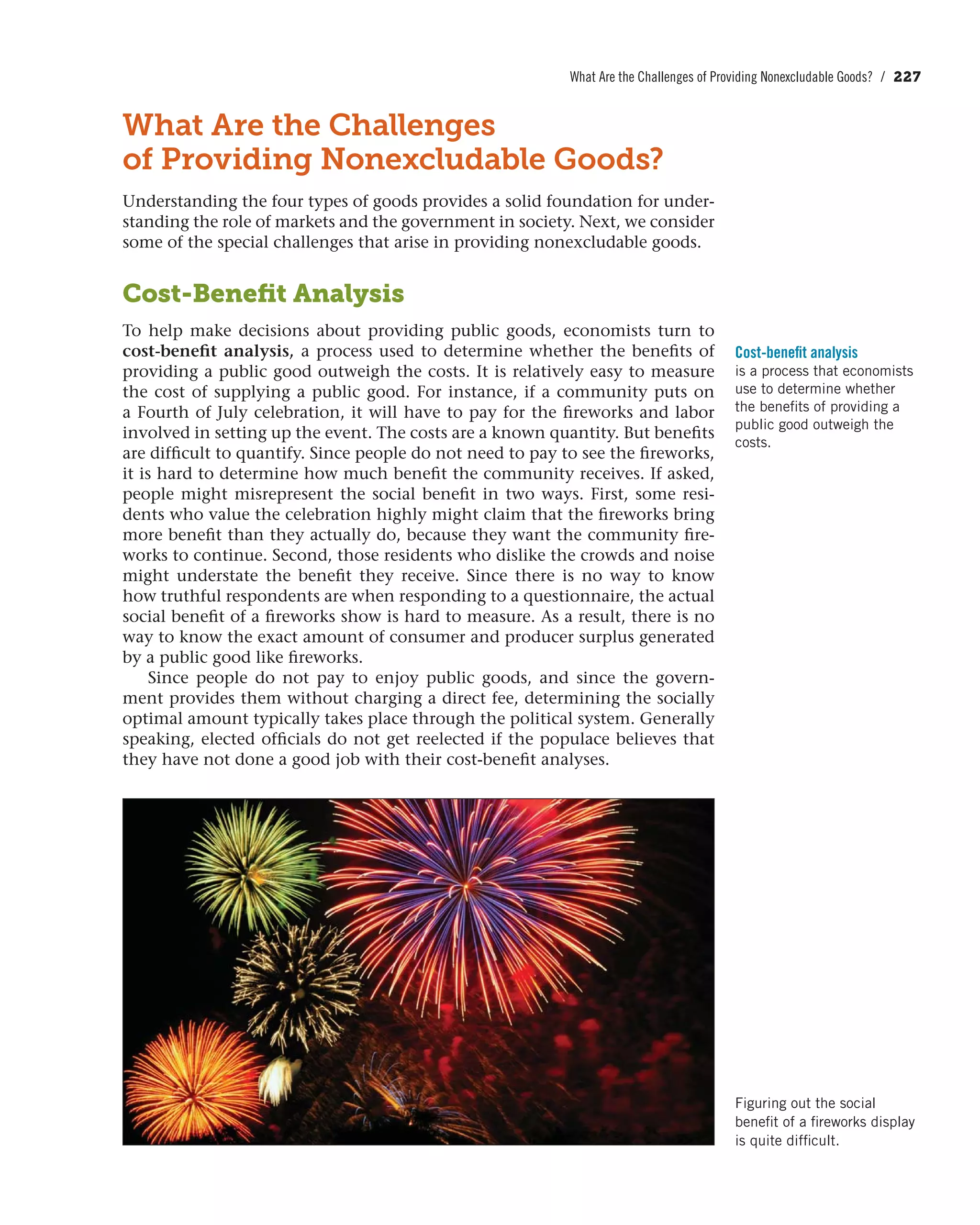

or injured pet get better. (Of course, pet care is not perfectly inelastic,

because there is certainly a price beyond which some pet owners would

not or could not pay; but for illustrative purposes, let’s say that pet care

is perfectly elastic.) For these pet owners, the demand curve is a vertical

line. If you look along the Quantity axis, you will see that the quantity

of pet care demanded (QD) remains constant no matter what it costs. At

For many pet owners, the demand

for veterinary care is perfectly

inelastic.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-171-2048.jpg)

![128 / CHAPTER 4 Elasticity

The Price Elasticity of Demand

In this section, there are two questions to give you practice computing the

price elasticity of demand. Before we do the math, ask yourself whether you

think the price elasticity of demand for either subs or the antibiotic amoxicillin

is elastic.

Question: A store manager decides to lower the price of a featured sandwich from $3

to $2, and she finds that sales during the week increase from 240 to 480 sandwiches.

Is demand elastic?

Answer: Consumers were flexible and bought significantly more sandwiches in

response to the price drop. Let’s calculate the price elasticity of demand (ED)

using Equation 4.2. Recall that

ED =

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(P2 - P1) , [(P1 + P2) , 2]

Plugging in the values from above yields

ED =

(480 - 240) , [(240 + 480) , 2]

($2 - $3) , [($2 + $3) , 2]

=

240 , 360

-$1 , $2.50

Therefore, ED = -1.67.

Whenever the price elasticity of demand is less than -1, demand is consid-

ered elastic: the percentage change in the quantity demanded is greater than

the percentage change in price. This outcome is exactly what the store man-

ager expected. But subs are just one option for a meal; there are many other

choices, such as salads, burgers, and chicken—all of which cost more than

the now-reduced sandwich. Therefore, we should not be surprised that there

is a relatively large percentage increase in sub purchases by price-conscious

customers.

Question: A local pharmacy manager decides to raise the price of a 50-pill prescription

of amoxicillin from $8 to $10. The pharmacy tracks the sales of amoxicillin over the next

month and finds that sales decline from 1,500 to 1,480 boxes. Is the price elasticity of

demand elastic?

Answer: First, let’s consider the potential substitutes for amoxicillin. To

be sure, it’s possible to substitute other drugs, but they might not be as

effective. Therefore, most patients prefer to use the drug prescribed by their

doctor. Also, in this case the cost of the drug is relatively small. Finally,

patients’ need for amoxicillin is a short-run consideration. They want the

medicine now so they will get better! All three factors would lead us to believe

that the demand for amoxicillin is relatively inelastic. Let’s find out if that

intuition is confirmed in the data.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Is the demand for amoxicillin

elastic or inelastic?

(CONTINUED)

Is the demand for a sub

elastic or inelastic?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-182-2048.jpg)

![How Do Changes in Income and the Prices of Other Goods Affect Elasticity? / 129

have income elasticities between 0 and 1. For example,

expenditures on items such as milk, clothing, electricity, and

gasoline are unavoidable, and consumers at any income level

must buy them no matter what. Although purchases of neces-

sities will increase as income rises, they do not rise as fast as

the increase in income does. Therefore, as income increases,

spending on necessities will expand at a slower rate than the

increase in income.

Rising income enables consumers to enjoy significantly

more luxuries. This produces an income elasticity of demand

greater than 1. For instance, a family of modest means may

travel almost exclusively by car. However, as the family’s income rises, they

can afford air travel. A relatively small jump in income can cause the family

to fly instead of drive.

In Chapter 3, we saw that inferior goods are those that people will choose

not to purchase when their income goes up. Inferior goods have a nega-

tive income elasticity, because as income expands, the demand for the good

declines. We see this in Table 4.4 with the example of macaroni and cheese,

an inexpensive meal. As a household’s income rises, it is able to afford health-

ier food and more variety in the meals it enjoys. Consequently, the number

of times that mac and cheese is served declines. The decline in consumption

indicates that mac and cheese is an inferior good, and this is reflected in the

negative sign of the income elasticity.

The price elasticity of demand using the midpoint method is

ED =

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(P2 - P1) , [(P1 + P2) , 2]

Plugging in the values from the example yields

ED =

(1480 - 1500) , [(1480 + 1500) , 2]

($10 - $8) , [($8 + $10) , 2]

Simplifying produces this:

ED =

-20 , 1490

$2 , $9

Therefore, ED = -0.06. Recall that an ED near zero indicates that the price

elasticity of demand is highly inelastic, which is what we suspected. The price

increase does not cause consumption to fall very much. If the store manager had

been hoping to bring in a little extra revenue from the sales of amoxicillin, his

plan was successful. Before the price increase, the business sold 1,500 units

at $8, so revenues were $12,000. After the price increase, sales decreased to

1,480 units, but the new price is $10, so revenues now are $14,800. Raising

the price of amoxicillin helped the pharmacy make an additional $2,800 in

revenue.

(CONTINUED)

Air travel is a luxury good.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-183-2048.jpg)

![How Do Changes in Income and the Prices of Other Goods Affect Elasticity? / 131

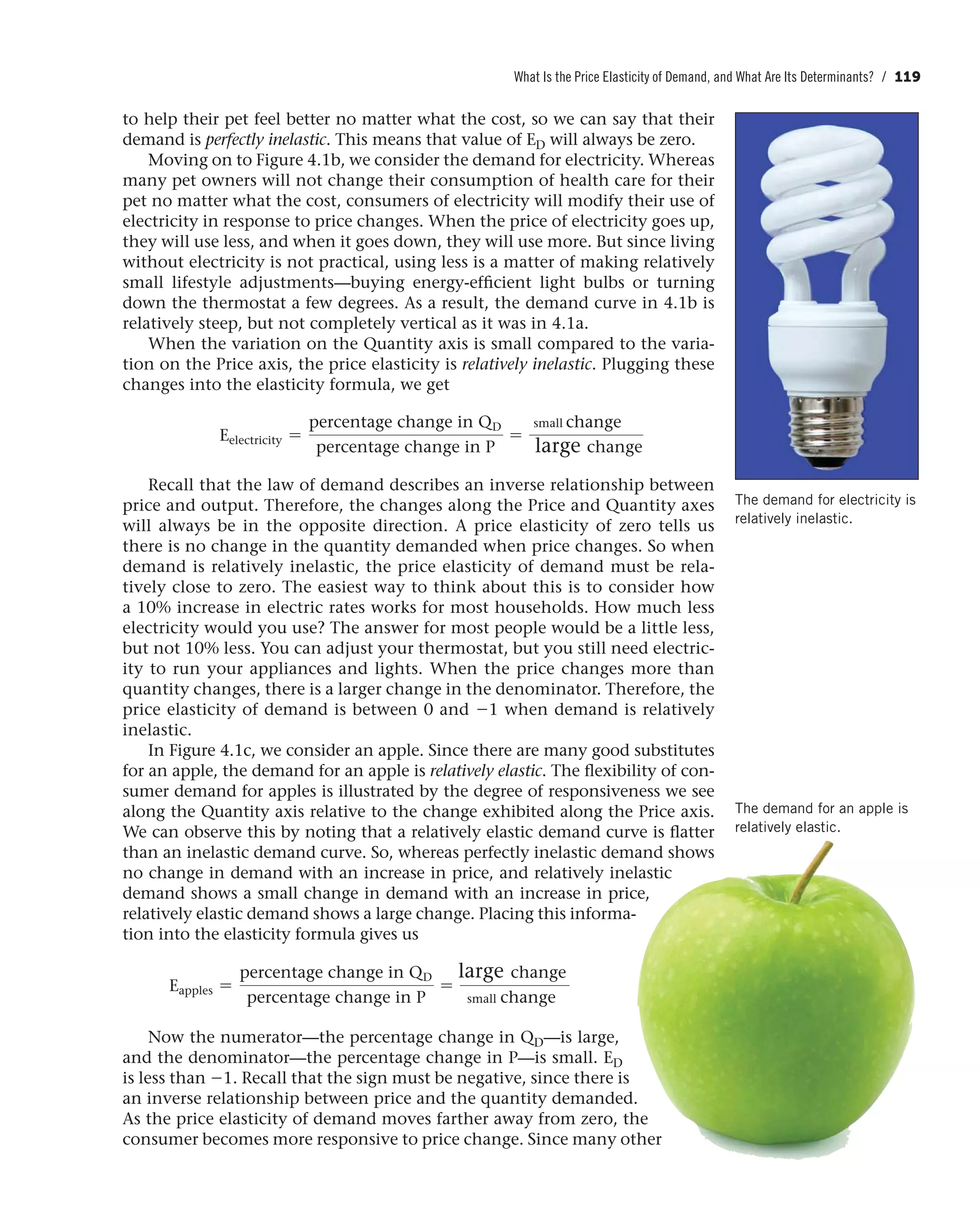

TABLE 4.5

Cross-Price Elasticity

Type of good EI coefficient Example

Substitutes EC 7 0 Pizza Hut and

Domino’s

No relationship EC = 0 A basketball and

bedroom slippers

Complements EC 6 0 Turkey and

gravy

delicious.” From this, we can construct a cross-price elastic-

ity example. Suppose that the price of a two-liter bottle of

Mr. Pibb falls from $1.49 to $1.29. In the week immediately

preceding the price drop, a local store sells 60 boxes of Red

Vines. After the price drop, sales of Red Vines increase to 80

boxes. Let’s calculate the cross-price elasticity of demand

for Red Vines when the price of Mr. Pibb falls from $1.49 to

$1.29.

The cross-price elasticity of demand using the midpoint

method is

EC =

(QRV2 - QRV1) , [(QRV1 + QRV2) , 2]

(PMP2 - PMP1) , [(PMP1 + PMP2) , 2]

Notice that there are now additional subscripts to denote that we are measur-

ing the percentage change in the quantity demanded of good RV (Red Vines)

in response to the percentage change in the price of good MP (Mr. Pibb).

Plugging in the values from the example yields

EC =

(80 - 60) , [(60 + 80) , 2]

($1.29 - $1.49) , [($1.49 + $1.29) , 2]

Simplifying produces

EC =

20 , 70

-$0.20 , $1.39

Solving for EC gives us a value of -1.01. Because the result is a negative value,

this confirms our intuition that two goods that go well together (“crazy deli-

cious”) are complements, since the decrease in the price of Mr. Pibb causes

consumers to buy more Red Vines.

Have you tried Mr. Pibb and Red Vines together?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-185-2048.jpg)

![134 / CHAPTER 4 Elasticity

Income Elasticity

Question: A college student eats ramen noodles twice

a week and earns $300/week working part-time. After

graduating, the student earns $1,000/week and eats

ramen noodles every other week. What is the student’s

income elasticity?

Answer: The income elasticity of demand using the midpoint method is

EI =

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(I2 - I1) , [(I1 + I2) , 2]

Plugging in yields

EI =

(0.5 - 2.0) , [(2.0 + 0.5) , 2]

($1000 - $300) , [($300 + $1000) , 2]

Simplifying yields

EI =

-1.5 , 1.25

$700 , $650

Therefore, EI = -1.1.

The income elasticity of demand is positive for normal goods and negative

for inferior goods. Therefore, the negative coefficient indicates that ramen noo-

dles are an inferior good over the range of income—in this example, between

$300 and $1,000. This result should confirm your intuition. The higher post-

graduation income enables the student to substitute away from ramen noodles

and toward other meals that provide more nourishment and enjoyment.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Yummy, or all you can afford?

What Is the Price Elasticity of Supply?

Sellers, like consumers, are sensitive to price changes. However, the determi-

nants of the price elasticity of supply are substantially different from the deter-

minants of the price elasticity of demand. The price elasticity of supply is a

measure of the responsiveness of the quantity supplied to a change in price.

In this section, we examine how much sellers respond to price changes.

For instance, if the market price of gasoline increases, how will oil companies

respond? The answer depends on the elasticity of supply. Oil must be refined

into gasoline. If it is difficult for oil companies to increase their output of

gasoline significantly, even if the price increases a lot, the quantity of gasoline

supplied will not increase much. In this case, we say that the price elasticity

of supply is inelastic, or unresponsive. However, if the price increase is small

The price elasticity of supply

is a measure of the respon-

siveness of the quantity

supplied to a change in

price.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-188-2048.jpg)

![138 / CHAPTER 4 Elasticity

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

The Price Elasticity of Supply

Question: Suppose that the price of a barrel of oil increases

from $60 to $100. The new output is 2 million barrels a day,

and the old output is 1.8 million barrels. What is the price

elasticity of supply?

Answer: The price elasticity of supply using the

midpoint method is

ED =

(Q2 - Q1) , [(Q1 + Q2) , 2]

(P2 - P1) , [(P1 + P2) , 2]

Plugging in the values from the example yields

ES =

(2.0M - 1.8M) , [(1.8M + 2.0M) , 2]

($100 - $60) , [($60 + $100) , 2]

Simplifying yields

ES =

0.2M , 1.9M

$40 , $80

Therefore, ES = 0.20.

Recall from our discussion of the law of supply that there is a direct

relationship between the price and the quantity supplied. Since ES in this case

is positive, we see that output rises as price rises. However, the magnitude

of the output increase is quite small—this is reflected in the coefficient 0.20.

Because oil companies cannot easily change their production process, they

have a limited ability to respond quickly to rising prices. That inability is

reflected in a coefficient that is relatively close to zero. A zero coefficient

would mean that suppliers could not change their output at all. Here suppliers

are able to respond, but only in a limited capacity.

Oil companies have us

over a barrel.

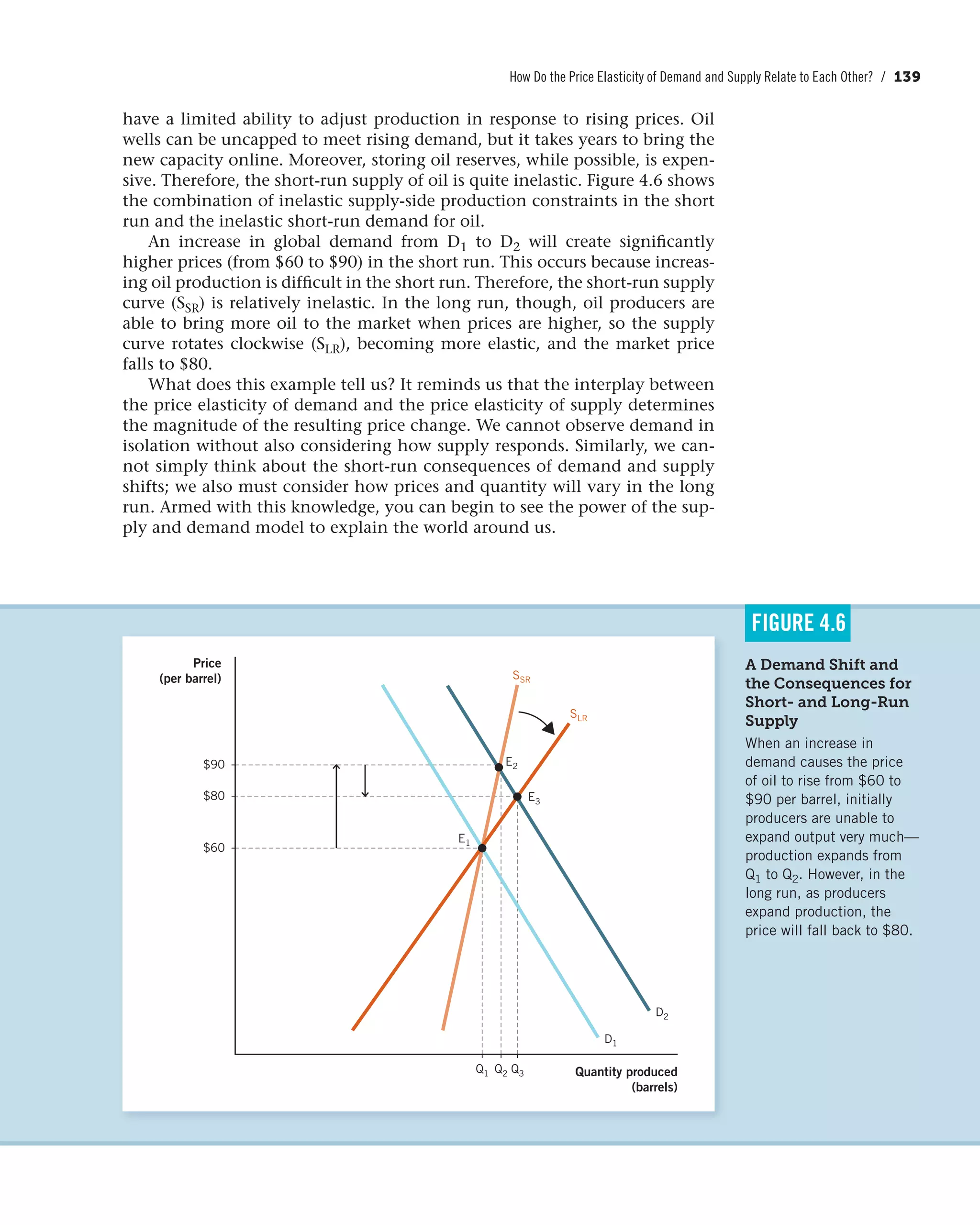

How Do the Price Elasticity of Demand

and Supply Relate to Each Other?

The interplay between the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of

demand allows us to explain more fully how the economy operates. With an

understanding of elasticity at our disposal, we can make a much richer and

deeper analysis of the world around us. For instance, suppose that we are con-

cerned about what will happen to the price of oil as economic development

spurs additional demand in China and India. An examination of the deter-

minants of the price elasticity of supply quickly confirms that oil producers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-192-2048.jpg)

![Conclusion / 145

SOLVED PROBLEMS

1. To answer this question, we need to consider

the price elasticity of demand. The tax is

only on gray T-shirts. This means that T-shirt

customers who buy other colors can avoid the

tax entirely—which means that the demand

for gray T-shirts is relatively elastic. Since not

many gray T-shirts will be sold, the govern-

ment will generate a small increase in rev-

enues from the tax.

9. In this question a worker gets a 25% raise, so

we can use this information in the denomina-

tor when determining the income elasticity

of demand. We are not given the percentage

change for the meals out, so we need to plug

in how often the worker ate out before (once

a week) and the amount he eats out after the

raise (twice a week).

Plugging into EI gives us

EI =

(2 - 1) , [(1 + 2) , 2]

0.25

Simplifying yields

EI =

1 , 1.5

0.25

Therefore, EI = 2.67.

The income elasticity of demand for eating out

is positive for normal goods. Therefore, eating

out is a normal good. This result should con-

firm your intuition.

Let’s see what happens with frozen lasagna once

the worker gets the 25% raise. Now he cuts back

on the number of lasagna dinners from once a

week to once every other week.

Plugging into EI gives us

EI =

(0.5 - 1) , [(1 + 0.5) , 2]

0.25

Simplifying yields

EI =

-0.5 , 0.75

0.25

Therefore, EI = -2.67. The income elasticity of

demand for having frozen lasagna is negative.

Therefore, frozen lasagna is an inferior good.

This result should confirm your intuition.

Solved Problems / 145](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-199-2048.jpg)

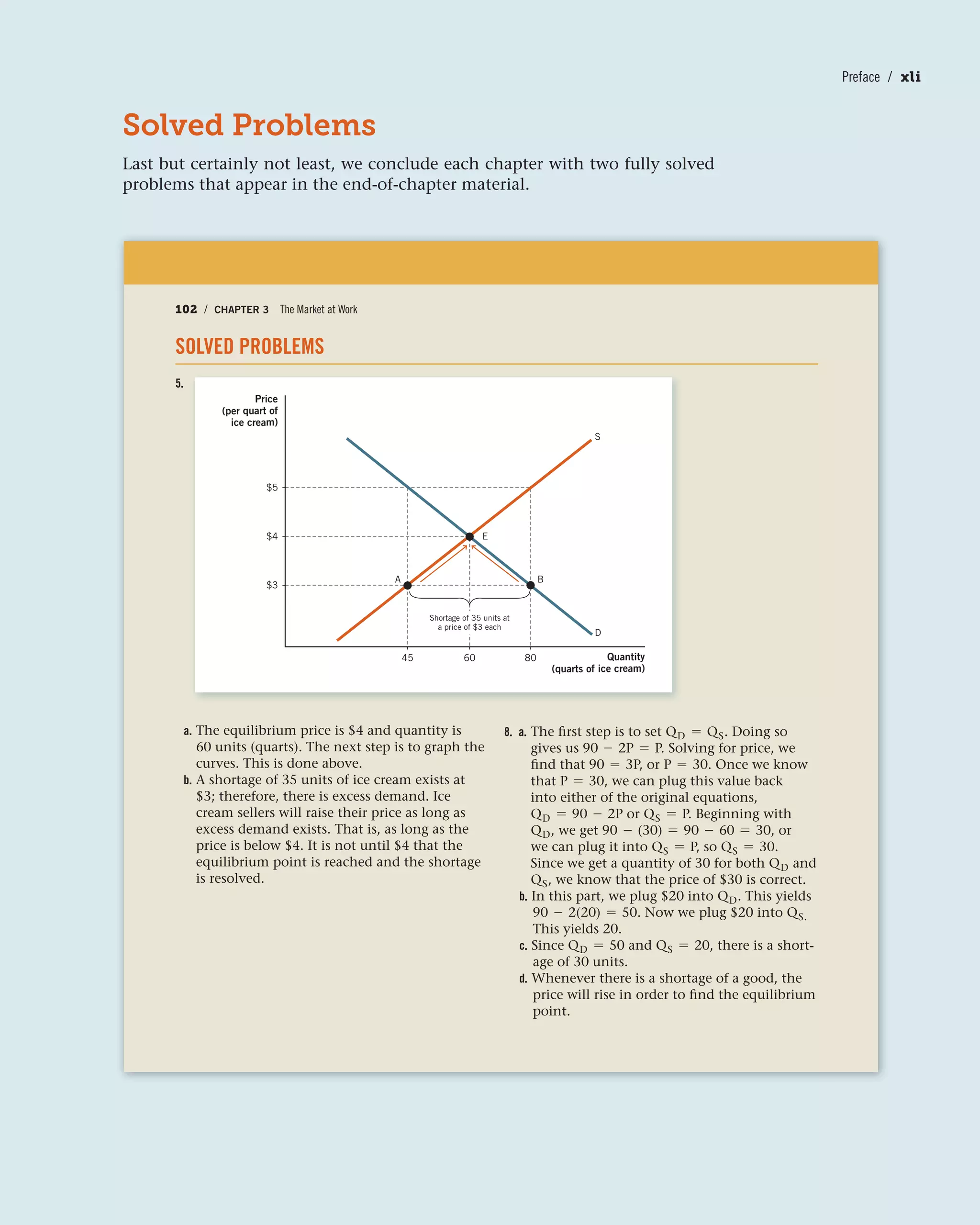

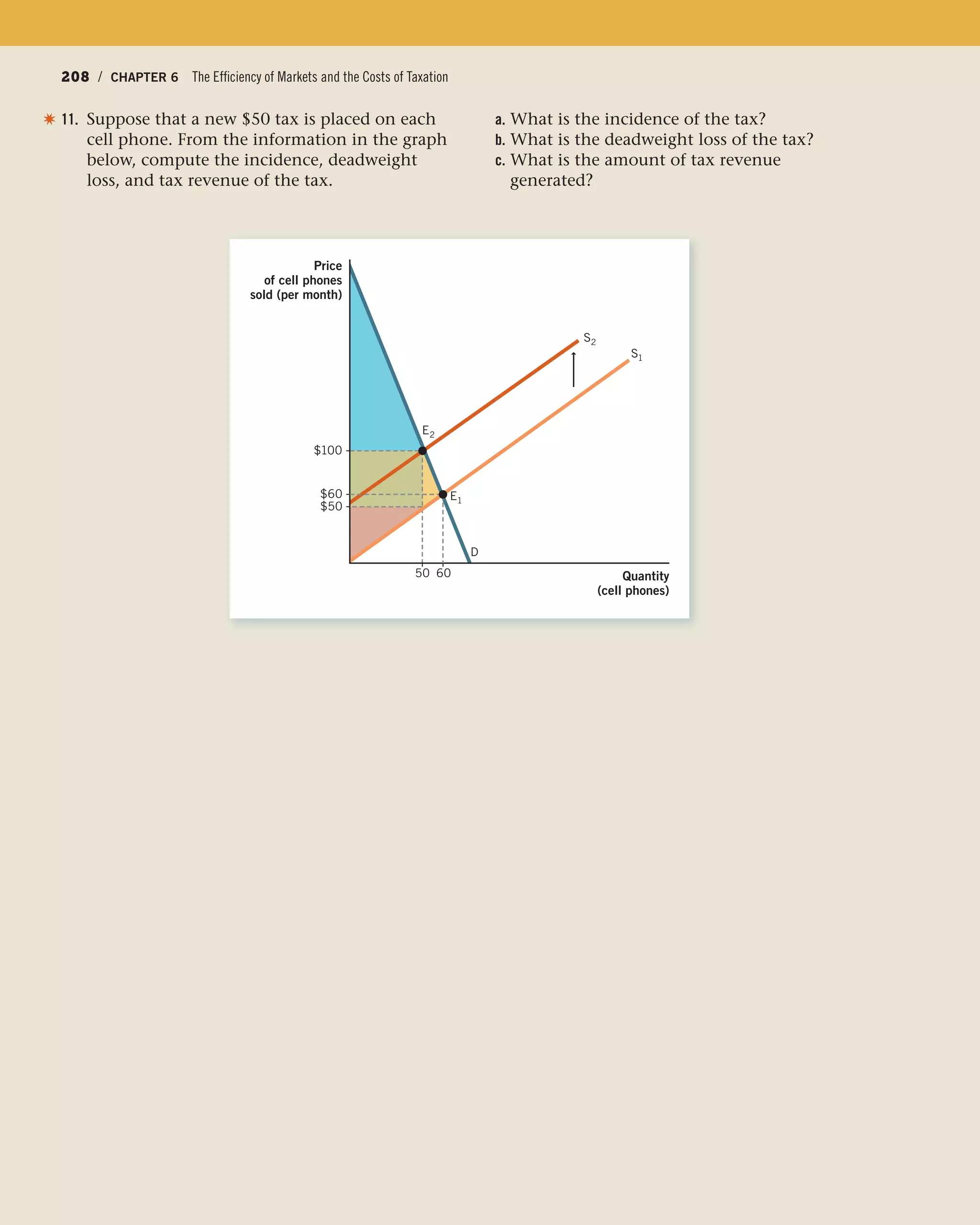

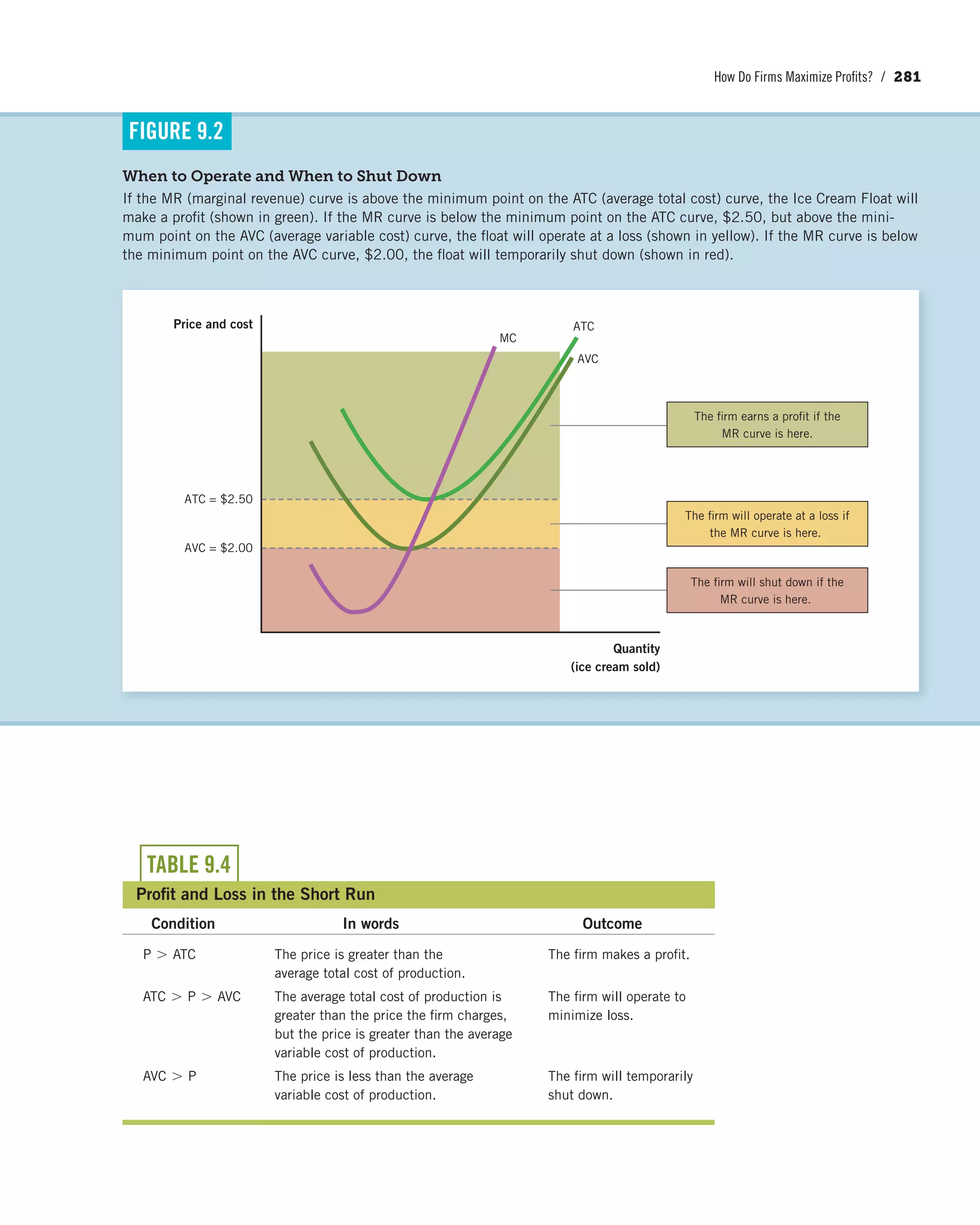

![Conclusion / 207

8. The cost of many electronic devices has fallen

appreciably since they were first introduced.

For instance, computers, cell phones, micro-

waves, and calculators not only provide more

functions but do so at a lower cost. Illustrate

the impact of lower production costs on the

supply curve. What happens to the size of the

consumer and producer surplus? If consumer

demand for cell phones is relatively elastic,

who is likely to benefit the most from the

lower production costs?

9. Suppose that the demand for a concert, QD,

is represented by the following equation,

where P is the price of concert tickets and

Q is the number of tickets sold:

QD = 2500 - 20P

The supply of tickets, QS, is represented by the

equation:

QS = -500 + 80P

a. Find the equilibrium price and quantity of

tickets sold. (Hint: Set QD = QS and solve

for the price, P, and then plug the result

back into either of the original equations to

find QE.)

b. Carefully graph your result in part a.

c. Calculate the consumer surplus at the equi-

librium price and quantity. (Hint: Since the

area of consumer surplus is a triangle, you

will need to use the formula for the area of

a triangle [1

2 * base * height] to solve the

problem.)

10. In this chapter, we have focused on the effect

of taxes on social welfare. However, govern-

ments also subsidize goods, or make them

cheaper to buy or sell. How would a $2,000

subsidy on the purchase of a new hybrid

vehicle impact the consumer surplus and

producer surplus in the hybrid market?

Use a supply and demand diagram to illustrate

your answer. Does the subsidy create dead-

weight loss?

Quantity

Price S2

C

D

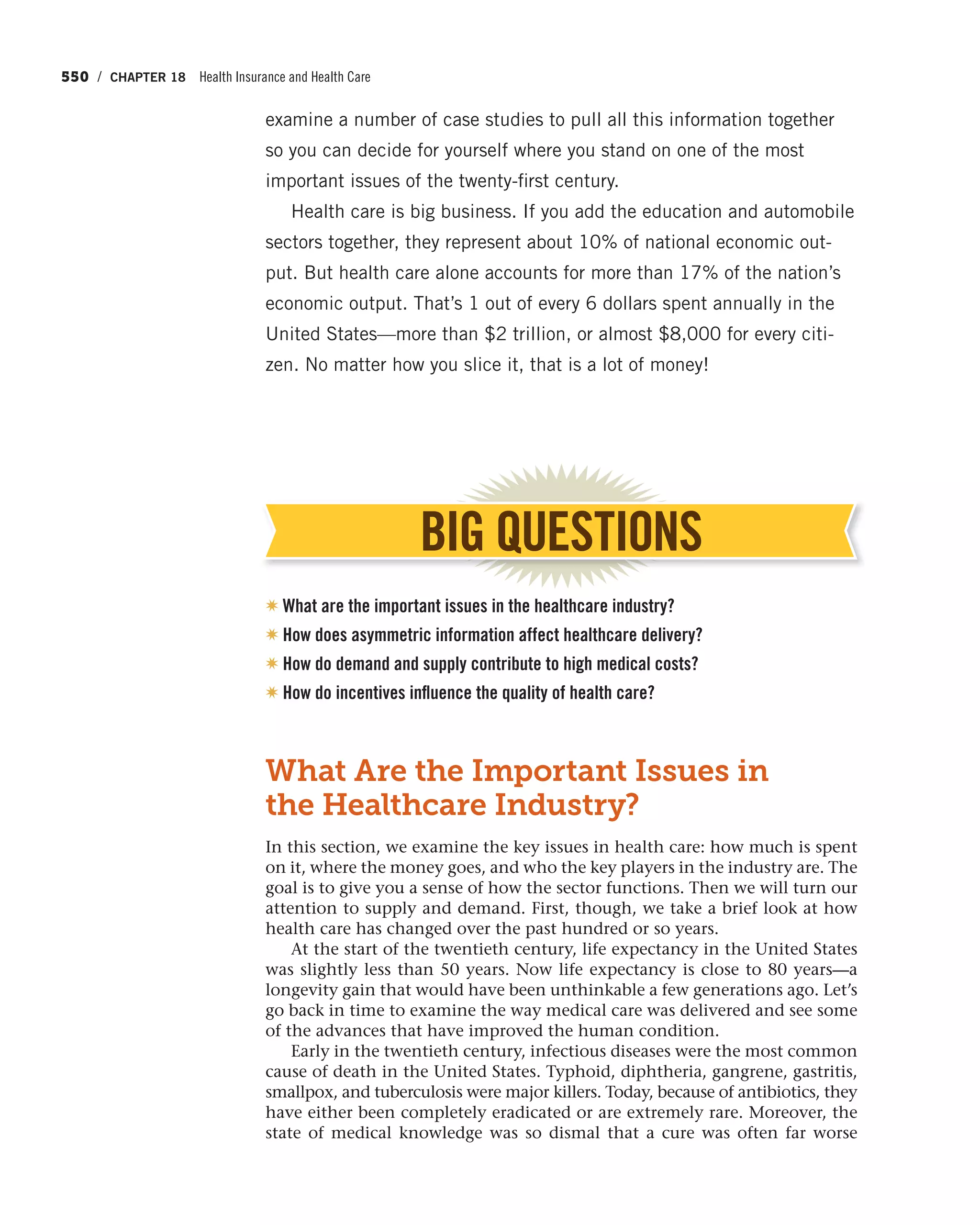

F

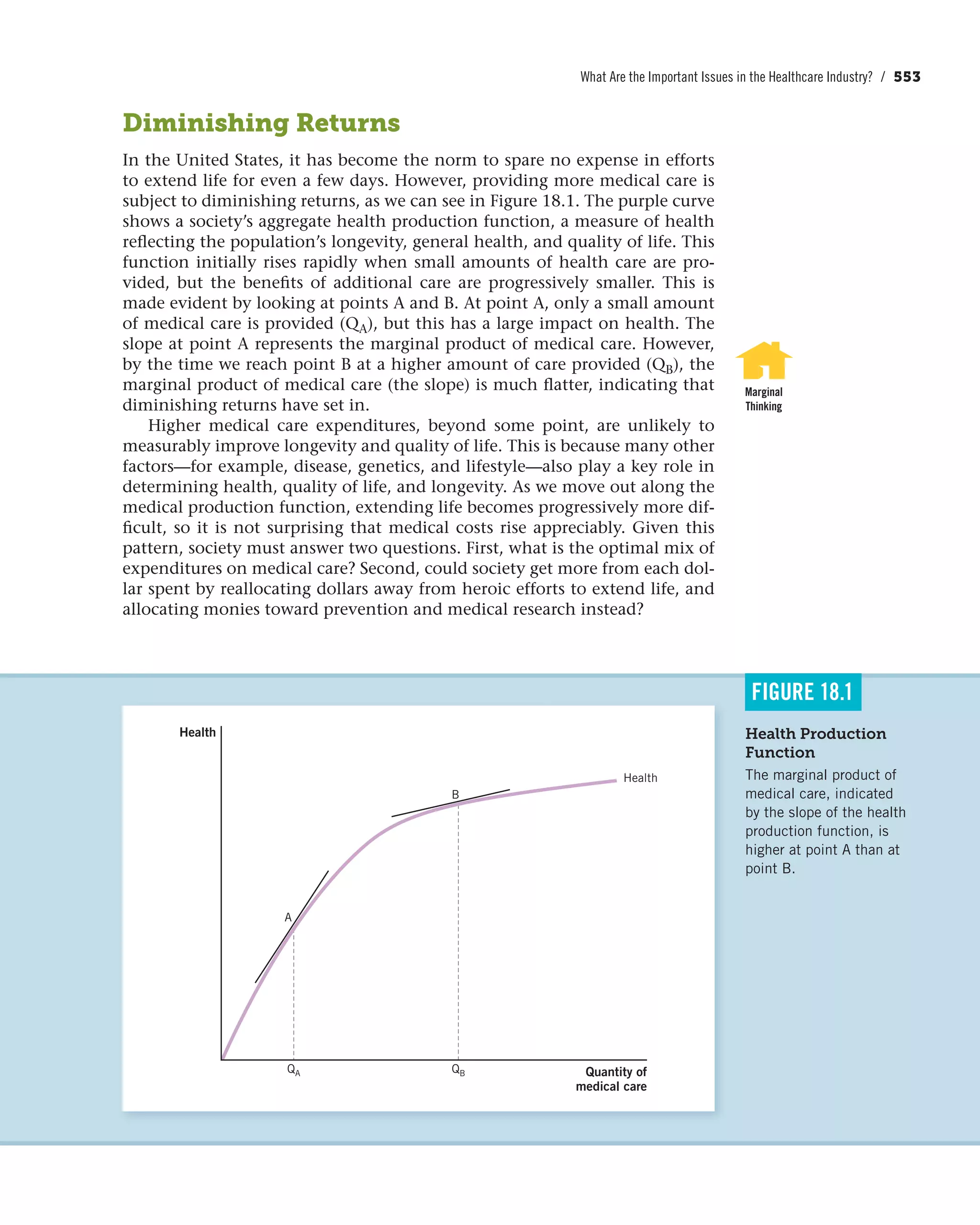

B

A

E

D

S1

Amount

of the tax

Tax

Study Problems / 207](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-261-2048.jpg)

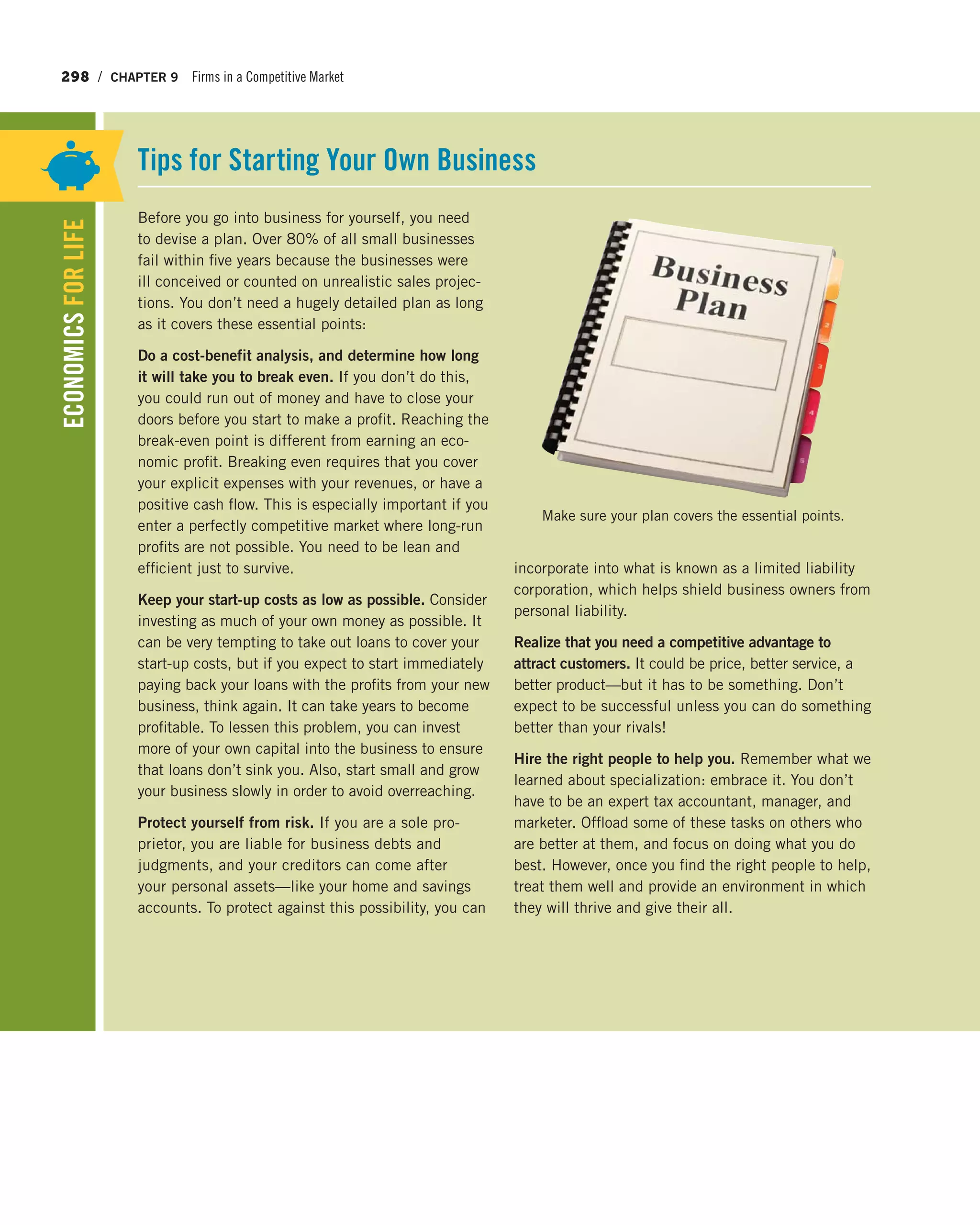

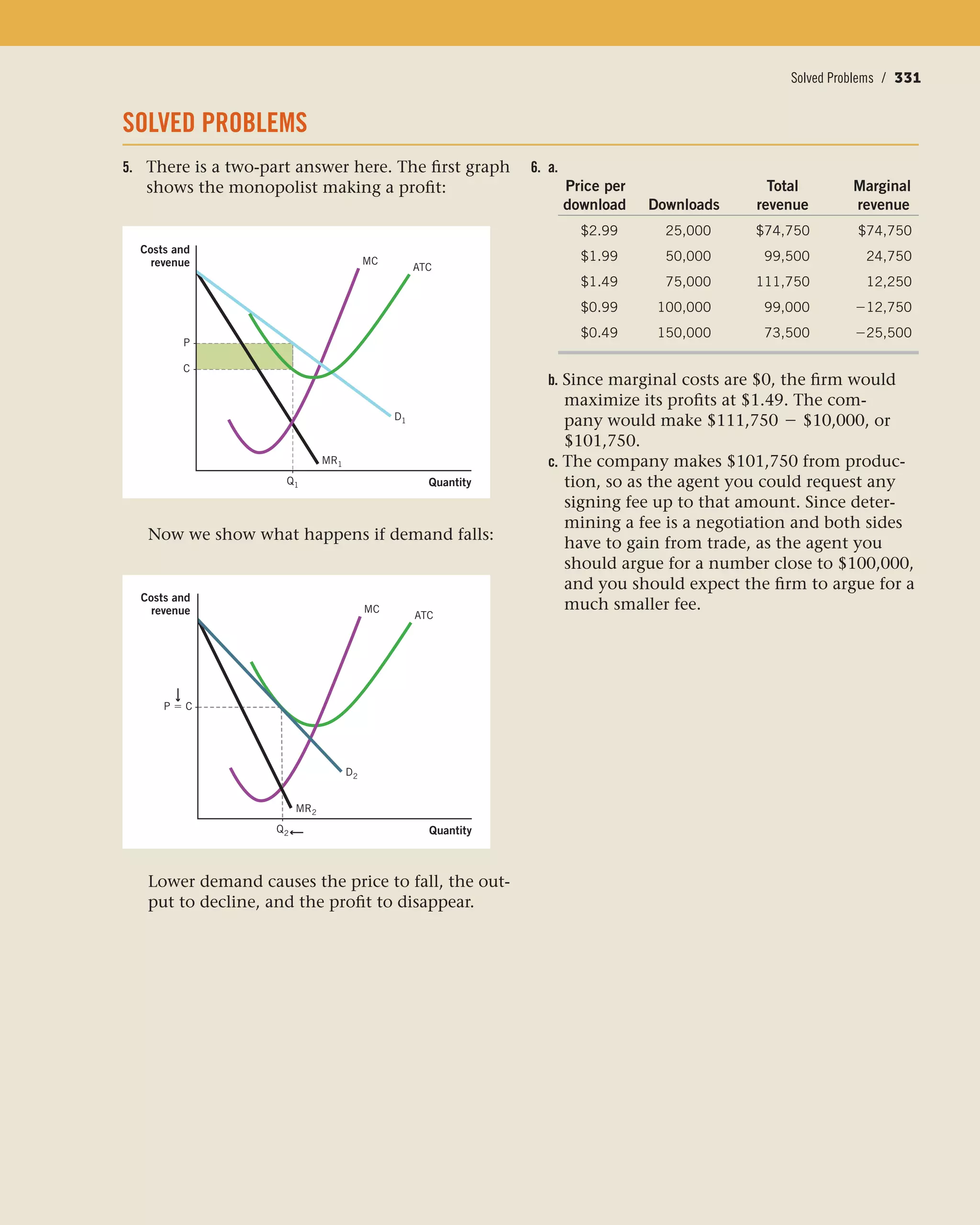

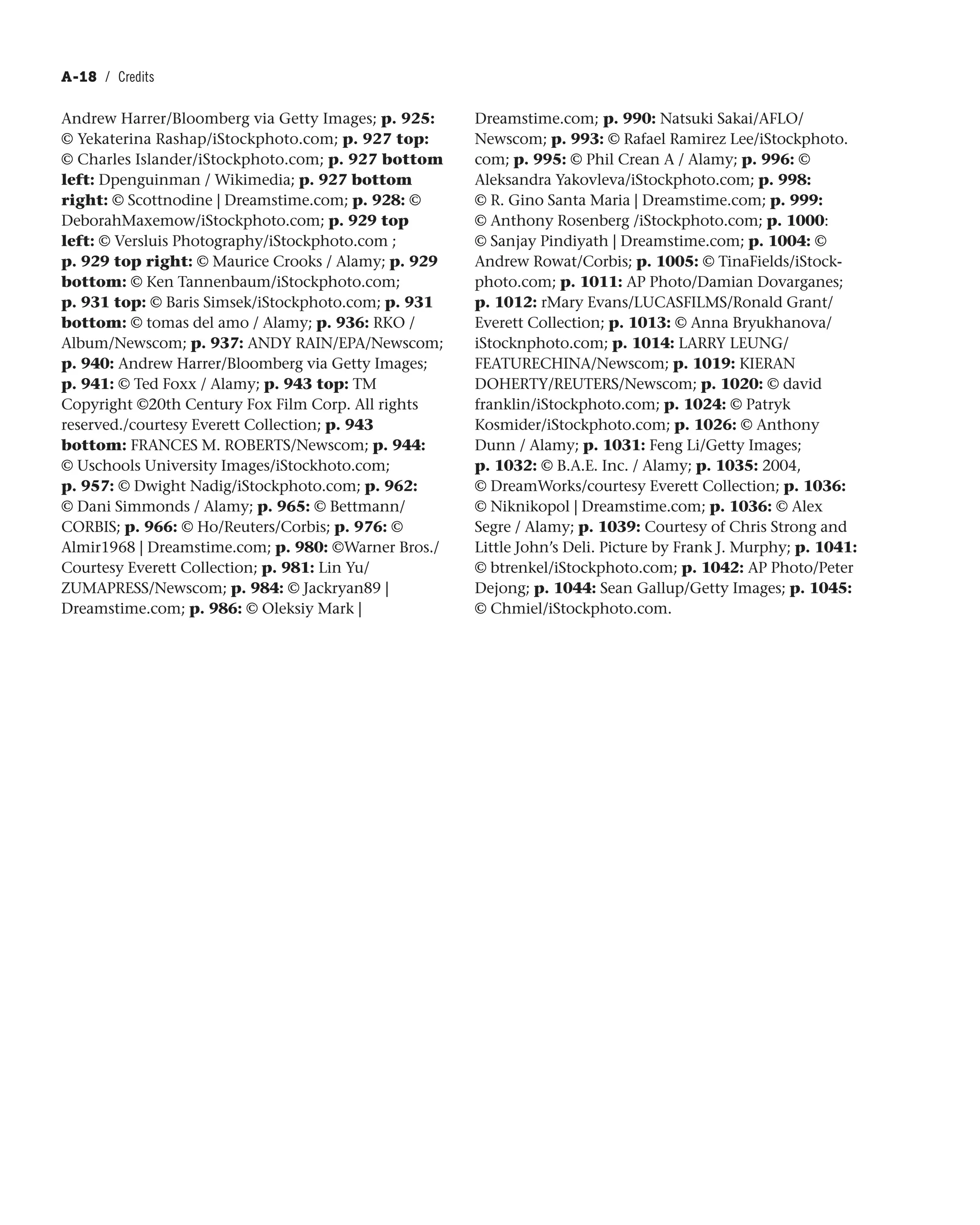

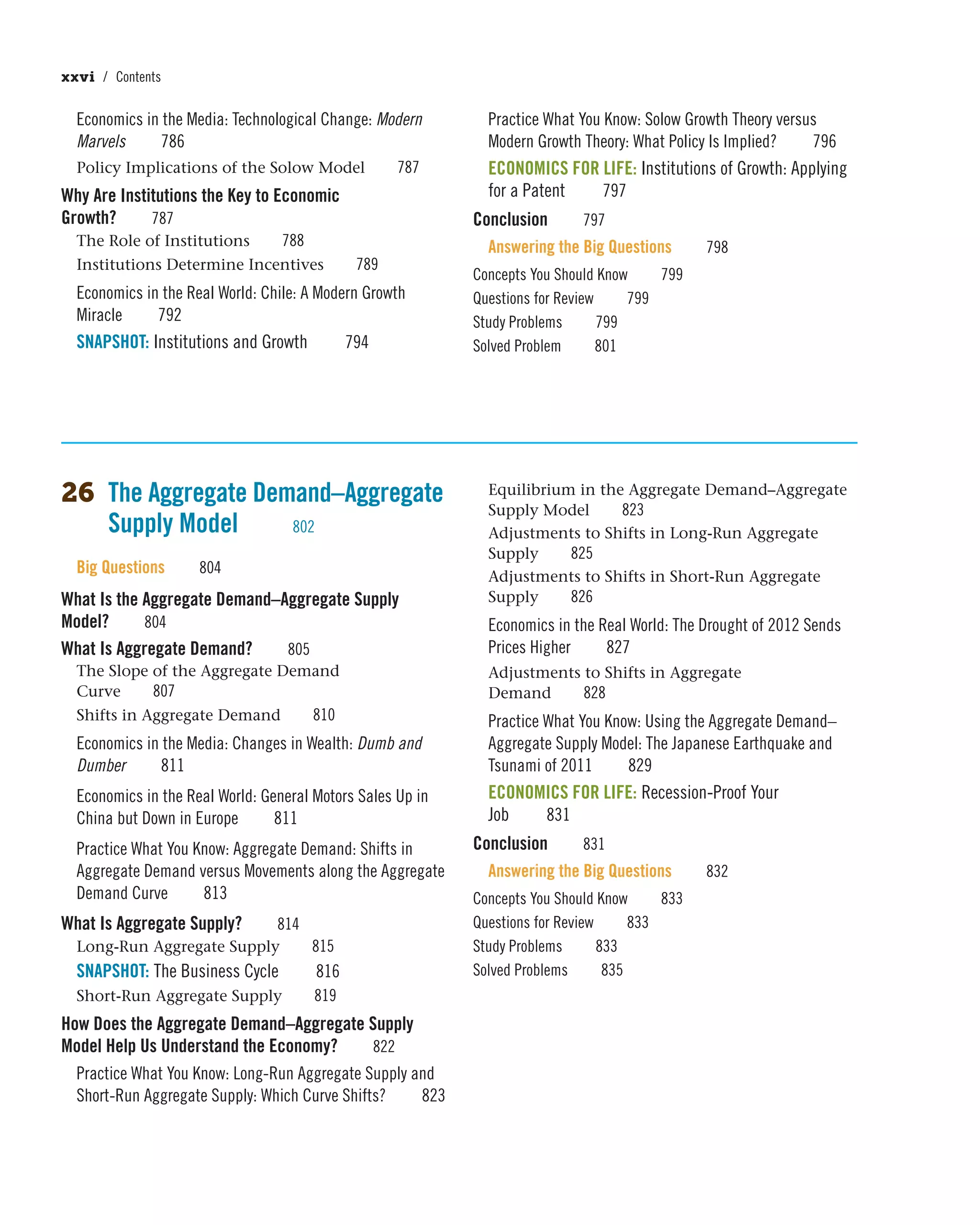

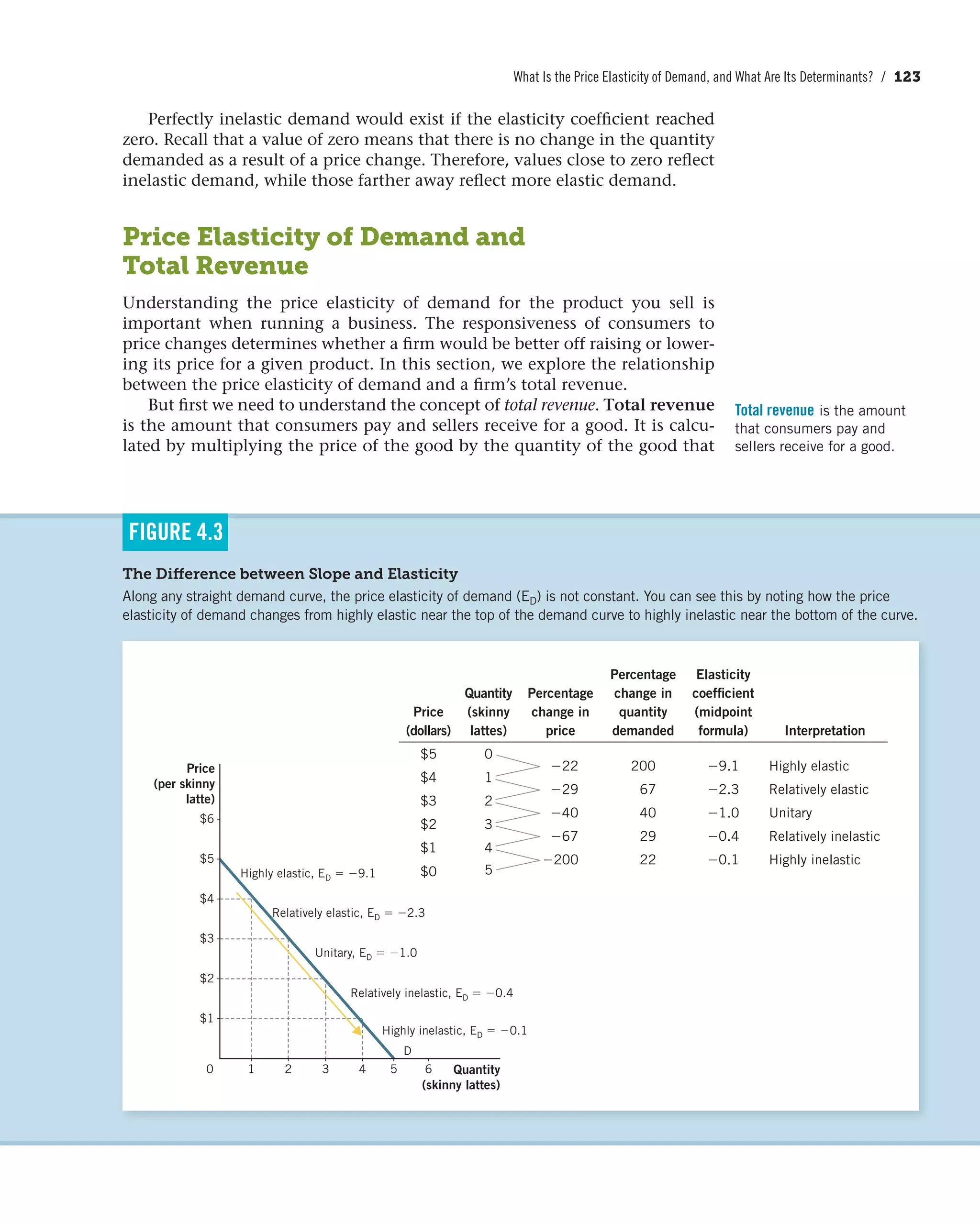

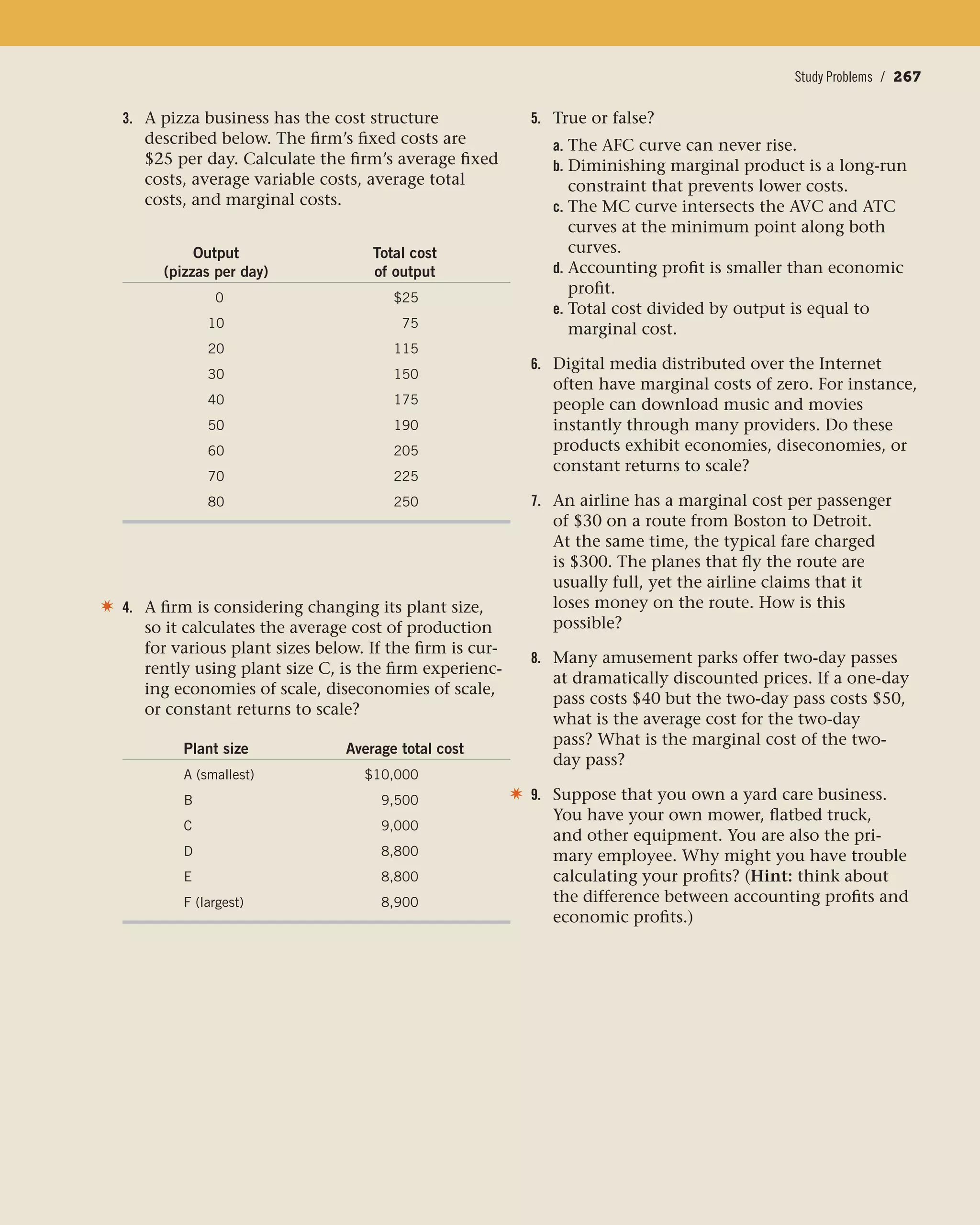

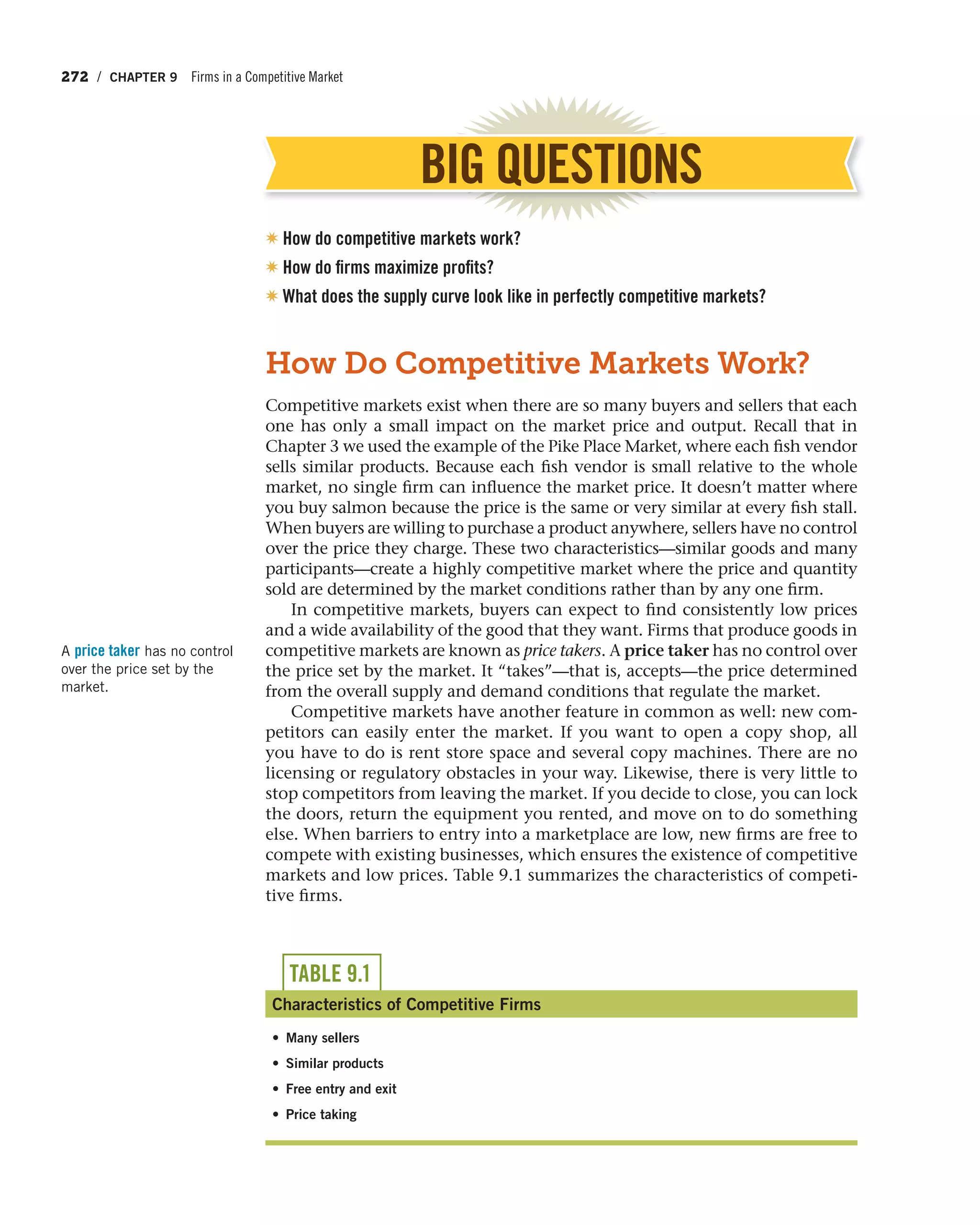

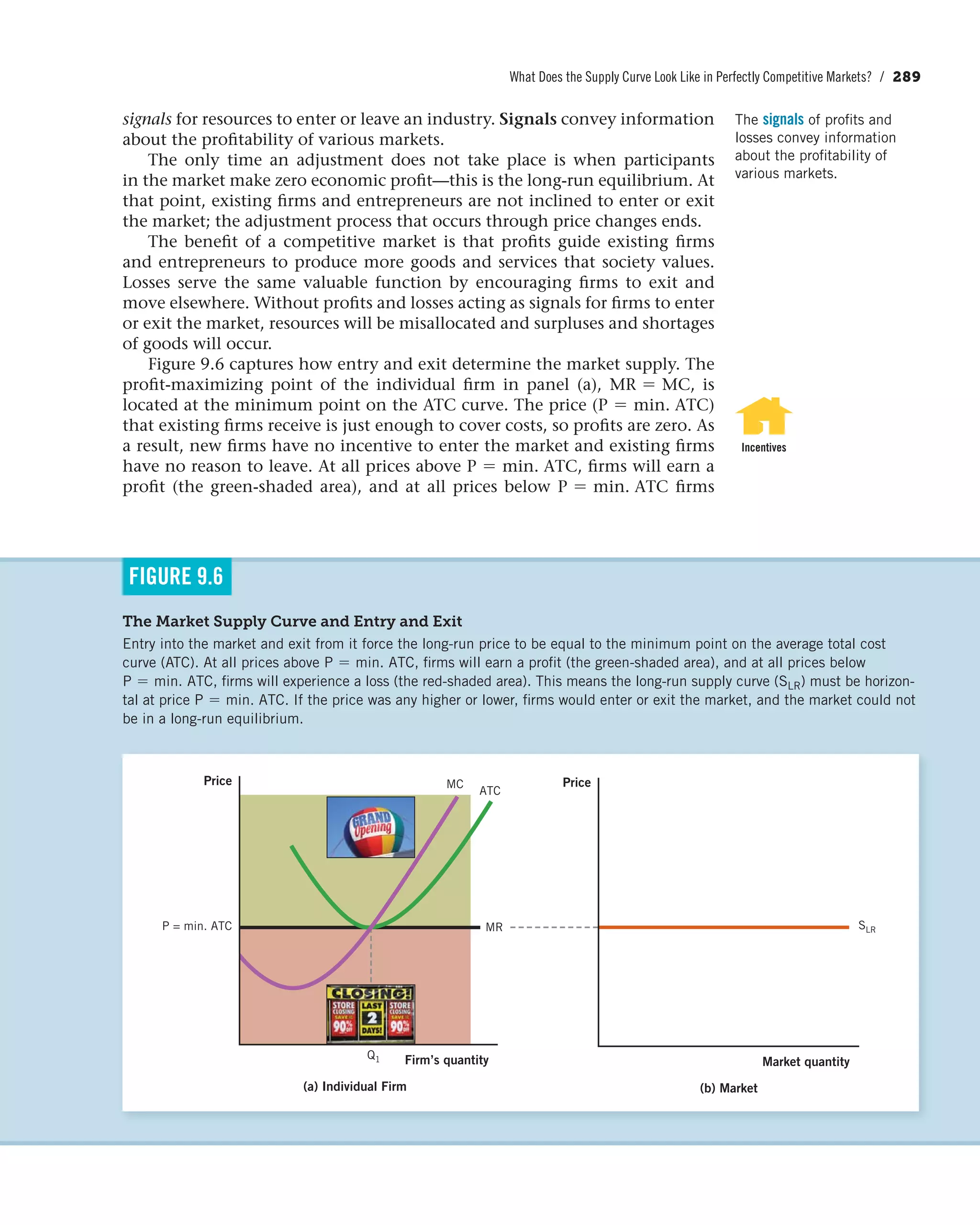

![How Do Firms Maximize Profits? / 279

Once we know the profit-maximizing quantity, we can determine the average

cost of producing Q units. From Q, we move up along the dashed line until

it intersects with the ATC curve. From that point, we move horizontally until

we come to the y axis. This tells us the average cost of making 8 units. Since

the total cost in Table 9.3 is $70 when 8 driveways are plowed, dividing 70 by

8 gives us $8.75 for the average total cost. We can calculate Mr. Plow’s profit

rectangle from Figure 9.1 as follows:

Profit = (Price - ATC[along the dashed line at quantity Q]) * Q

This gives us (10-8.75) * 8 = $10, which is the profit we see in Table 9.3,

column 4, in red numbers. Since the MR is the price, and since the price is

higher than the average total cost, the firm makes the profit visually repre-

sented in the green rectangle.

The Firm in the Short Run

Deciding how much to produce in order to maximize profits is the goal of

every business. However, there are times when it is not possible to make a

profit. When revenue is insufficient to cover cost, the firm suffers a loss—at

which point it must decide whether to operate or temporarily shut down.

Successful businesses make this decision all the time. For example, retail

Profit Maximization

Mr. Plow uses the profit-

maximizing rule to locate

the point at which marginal

revenue equals marginal

cost, or MR = MC. This

determines the ideal out-

put level, Q. The firm takes

the price from the market;

this is shown as the

horizontal MR curve where

price = $10.00. Since

the price charged is higher

than the average total cost

curve along the dashed

line at quantity Q, the

firm makes the economic

profit shown in the green

rectangle.

FIGURE 9.1

P = $10.00

Q = 8

ATC = $8.75

Price

and Cost

Quantity

(driveways plowed)

MC

Profit

Maximum profit

occurs here, where

MR = MC

ATC

MR

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-333-2048.jpg)

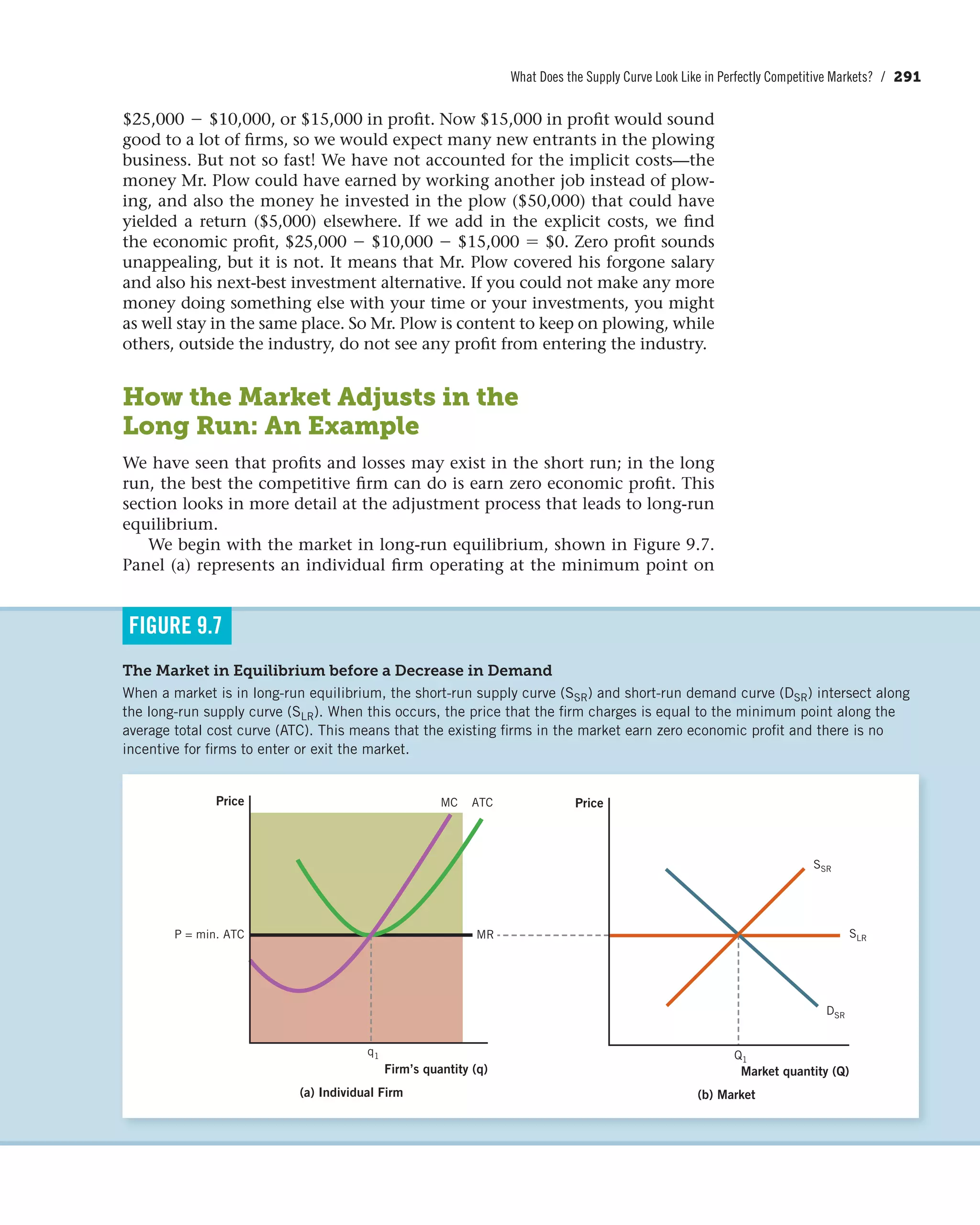

![What Does the Supply Curve Look Like in Perfectly Competitive Markets? / 293

I Love Lucy

I Love Lucy was the most watched television

comedy of the 1950s. The show featured two

couples who are best friends, the Ricardos and the

Mertzes, who find themselves in the most unlikely

situations.

One particular episode finds Ricky Ricardo disil-

lusioned with show business. After some conversa-

tion, Ricky and Fred Mertz decide to go into business

together and start a diner. Fred and Ethel Mertz have

the experience to run the diner, and Ricky plans to

use his name and star power to help get the word out

about the restaurant, which they name A Little Bit of

Cuba.

If you have seen any of the I Love Lucy series,

you already know that the business venture is des-

tined to fail. Sure enough, the Mertzes get tired of

doing all of the hard work—cooking and serving the

customers—while Ricky and Lucy Ricardo meet and

greet the guests. Things quickly deteriorate, and the

two couples decide to part ways. The only problem

is that they are both part owners, and neither can

afford to buy out the other. So they decide to split

the diner in half right down the middle!

The result is absurd and hilarious. On one side,

guests go to A Little Bit of Cuba. On the other side,

the Mertzes set up Big Hunk of America. Since both

restaurants use the same facilities and sell the same

food, the only way they can differentiate themselves

is by lowering their prices. This leads to a hamburger

price war to attract customers:

Ethel: “Three!”

Lucy: “Two!”

Ethel: “One-cent hamburgers.”

Fred: “Ethel, are you out of your mind?” [Even

in the 1950s, a penny was not enough

to cover the marginal cost of making a

hamburger.]

Ethel: “Well, I thought this could get ’em.”

Fred: “One-cent hamburgers?”

After the exchange, Lucy whispers in a

customer’s ear and gives him a dollar. He then

proceeds to Big Hunk of America and says,

“I’d like 100 hamburgers!”

Fred Mertz replies, “We’re all out of

hamburgers.”

How do the falling prices described here

affect the ability of the firms in this market to

make a profit?

The exchange is a useful way of visualizing how

perfectly competitive markets work. Competition forces

the price down, but the process of entry and exit takes

time and is messy. The Ricardos and Mertzes can’t

make a living selling one-cent hamburgers—one cent

is below their marginal cost—so one of the couples

will end up exiting. At that point, the remaining

couple would be able to charge more. If they end up

making a profit, that profit will encourage entrepre-

neurs to enter the business. As the supply of ham-

burgers expands, the price that can be charged will

be driven back down. Since we live in an economi-

cally dynamic world, prices are always moving toward

the long-run equilibrium.

Entry and Exit

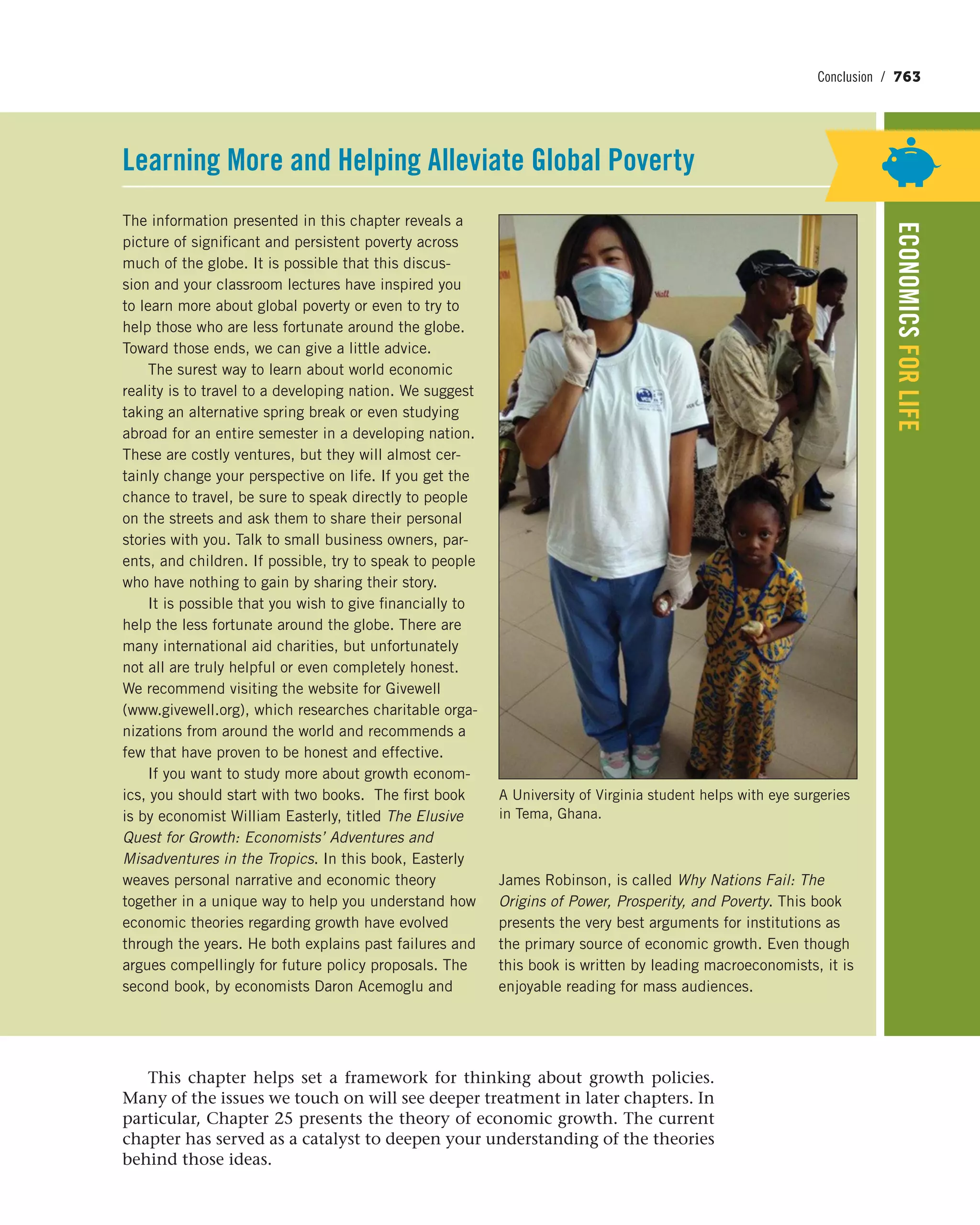

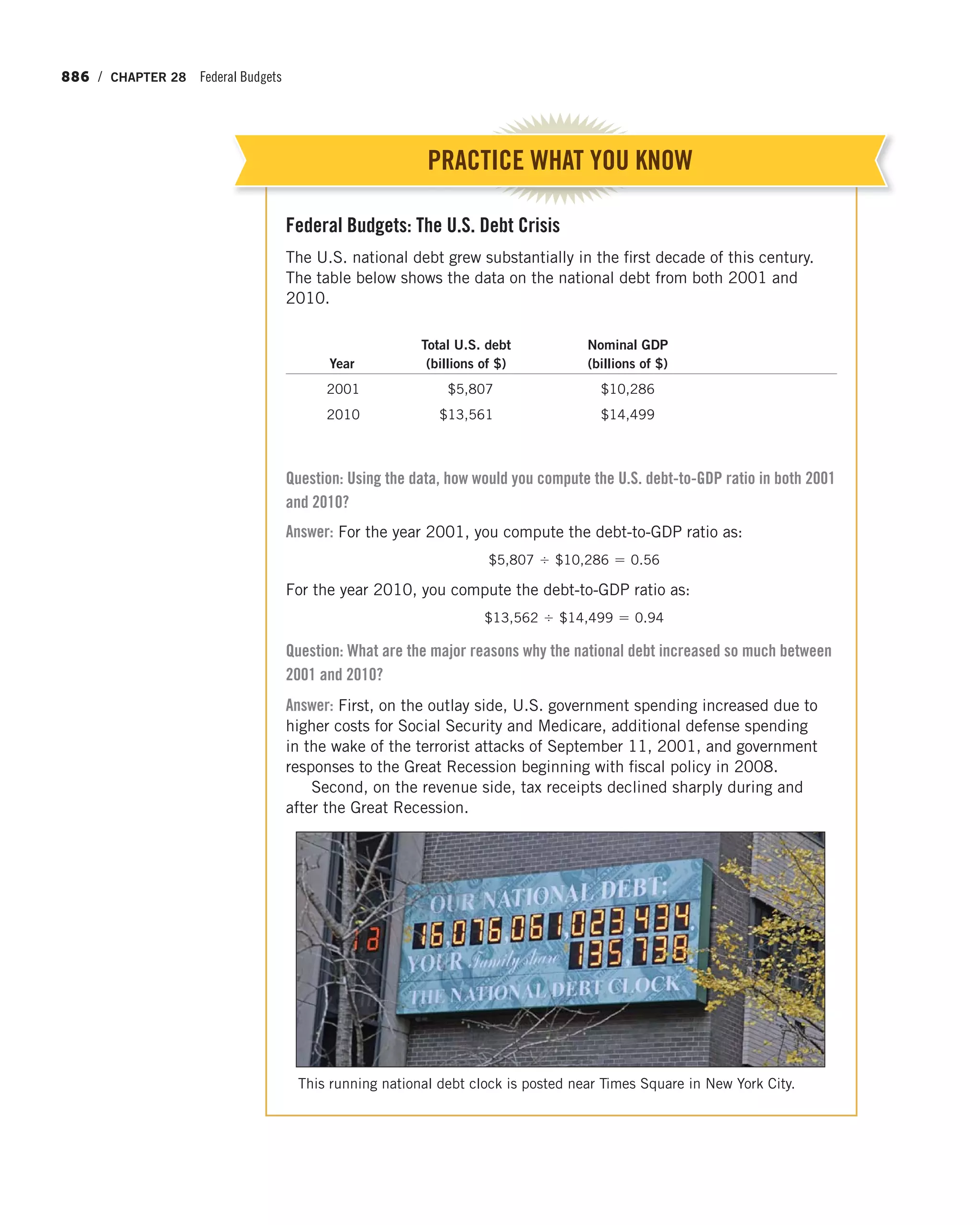

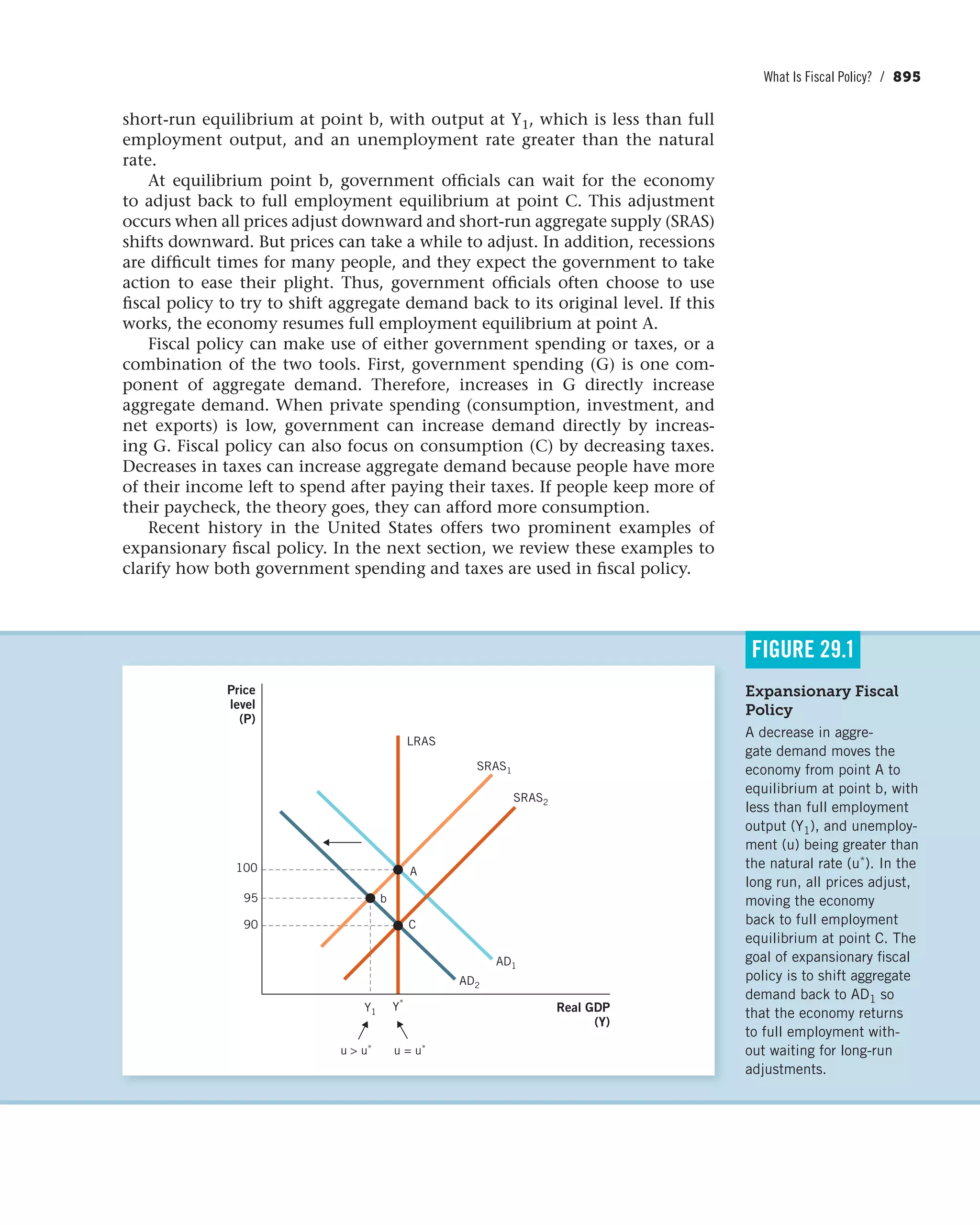

ECONOMICSINTHEMEDIA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principlesofeconomics-150728171823-lva1-app6892/75/Principles-of-economics-347-2048.jpg)