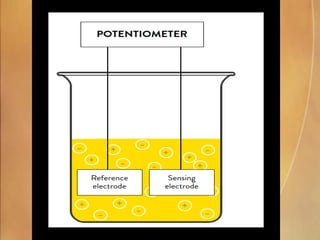

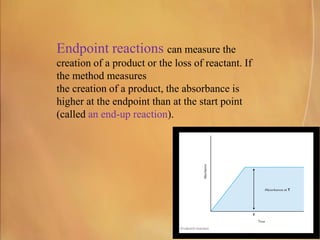

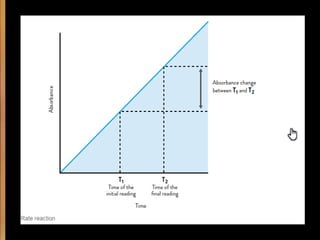

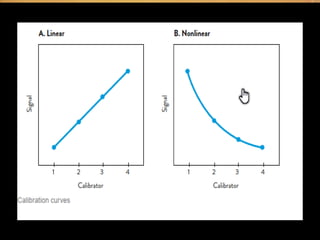

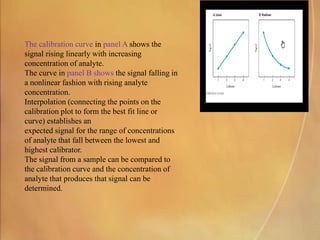

Potentiometry involves measuring electrical potential between electrodes to determine ion concentrations, with the Nernst equation describing the relationship between voltage change and ion activity. Endpoint and rate reactions are discussed as methods for quantifying analytes, with calibration being essential to relate analytical signals to concentrations. Challenges in calibration include determining the analytical measurement range, which can affect the reliability of results in clinical assays.