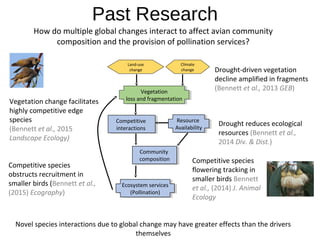

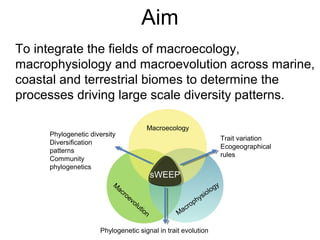

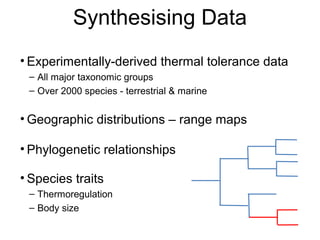

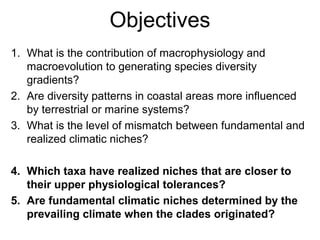

This document discusses research on how multiple global changes interact to affect avian community composition and pollination services. It summarizes past research that found vegetation decline from drought was amplified in fragmented areas, drought reduced ecological resources, and vegetation change facilitated competitive edge species. The aim of the synthesized worldwide ecology, evolution and physiology project is to integrate macroecology, macrophysiology and macroevolution across biomes to determine the processes driving large-scale diversity patterns. Some preliminary findings are that species' temperature tolerance relates to the prevailing climate when their order originated, and there is strong phylogenetic structure in temperature tolerance.

![• Species temperature tolerance is related to the

prevailing climate when their order originated

– Stronger for exothermic species

• Strong phylogenetic structure in species

temperature tolerance

Findings so fair

"Bali Barat mangroves" byRonfromNieuwegein/ SouthMoretonOxfordshire, Netherlands / UK - flickr: Taman Nasional Bali Barat (West Bali National Park). Licensedunder Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike2.0via WikimediaCommons -

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bali_Barat_mangroves.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Bali_Barat_mangroves.jpg

Christian Fischer [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia CommonsBy Stef Maruch (kelp-forest.jpg) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/postdocbennett2016-160429074452/85/Postdoc-bennett-2016-7-320.jpg)