This document is a senior design report for an observational tilt-rotor unmanned aerial system called Paparazzi. The report describes the design of the Paparazzi UAS, which combines the capabilities of fixed-wing aircraft and rotorcraft to take off and land vertically while also efficiently cruising long distances. Key aspects of the design include a 40 inch wingspan, 5.5 pound weight, ability to hover for 15 minutes and cruise 4 nautical miles at 40 knots. The report details the conceptual design process, mission profile, weight breakdown, and aerodynamic analysis performed to develop the Paparazzi UAS for applications such as military reconnaissance, search and rescue, and commercial delivery.

![11

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Figure 13. Paparazzi Aircraft Dimensions

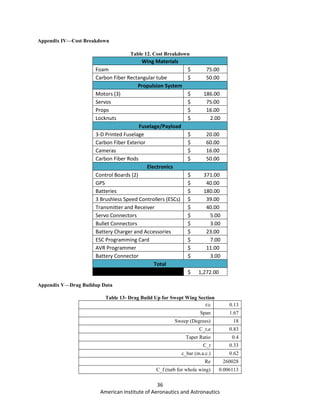

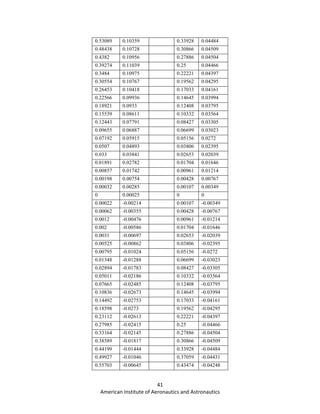

A tool was developed in Excel to estimate the drag of the UAS based on a buildup of the system’s various

components using Shevell’s method. This calculates the entire system drag by summing the drag of each of the

system’s structures, according to the equation:

∑ (2)

Where K is defined as,

[ ( ) ( ) ]

( ) ⁄

√ ⁄

(3)

The skin friction coefficient was calculated using a simplified assumption of entirely turbulent flow. It was

assumed that the flow was tripped to turbulent flow at .01 inches on each component. The summed components of

the plane include the rectangular portion of the wing, the engine nacelles, the fuselage, and the tail. With the given

dimensions specified in Table 3, a Reynolds number was calculated for each surface of the aircraft.

Table 3. Freestream Parameters

Pressure (psf) 2051

Density (lbs./ft2

) 2.32E-03

Velocity (ft/s) 67.5

Viscosity (lb ft-1

s-1

) 3.73E-07

Mach Number (M) 0.06

Speed of Sound (ft/s) 1113

Dynamic Pressure (psf) 5.28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-12-320.jpg)

![13

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

provide enough thrust in horizontal flight to reach the cruise speed. For efficiency in vertical thrust mode a propeller

with large diameter and low pitch is desired as opposed to horizontal thrust where low diameter and higher pitch is

ideal. By analyzing different propeller combinations with our motor in MotoCalc, software commonly used to

predict RC aircraft performance, a propeller that is 12”x8” was selected. This offers the minimum thrust with this

motor needed to reach the cruise speed of 40 knots while having the largest diameter and lowest pitch possible for

the highest efficiency during vertical thrust.

F. Constraint Analysis

An initial constraint analysis tool was developed in Excel with estimated data and then adjusted iteratively as

various design assumptions became more strongly defined. As aircraft and helicopter designs are constrained by

separate parameters, the analysis had to consider the vertical thrust configuration and the forward configuration

constraints separately. Primarily, the limiting values for helicopter takeoff and hovering is power loading and disk

loading. For an aircraft, these values would be power loading and wing loading. While the power loading constraint

is inherently related, each configuration will use a separate throttle setting which will consequently affect the power

required.

The following equation was used to determine the power required for vertical climb at various disk loadings out

of ground effect:

[( √ ) ] [ ] (7)

It should be noted that this equation also applies for hovering flight by setting the climb velocity to zero.

Intuitively, it also becomes apparent that the air vehicle will have enough power to hover if the vehicle has the

power required for climb. Therefore, a climb rate of 120 fpm was assumed to allow the air vehicle to reach an

altitude of 20 feet in 10 seconds. The adjustment for the force of downwash blowing on the vehicle was assumed to

be 3% of the disk loading. Additionally, the figure of merit was assumed to be 0.7 to compensate power losses due

to factors such as airfoil profile drag, nonuniform flow, tip losses, and slipstream effects. The mechanical efficiency

was approximated to be 0.97. Although this analysis considers the power required out of ground effect, the actual

power required during takeoff in ground effect is decreased. However, in an effort to design with conservative

assumptions and allow excess power for maneuvering, ground effect was neglected for power calculations.

Using an assumed weight of 5.50 lbs, the power loading was plotted versus the disk loading. In the figure below,

the area above the curve represents an inoperable region, where there is not sufficient power to takeoff at 120 fpm.

The area below the curve is the design space which meets VTOL power requirements. The design point for climb

was selected to be a power loading of 5.7 lbs/hp at a disk loading of 7.0 lbs/ft2

. With the current engine and propeller

combination, this occurs at an 80% throttle setting, which is the upper limit for our desired maneuvering mission.

With the design point falling beneath the curve, there is a surplus of power available as a margin of safety which

could also be used to accelerate the vehicle upwards at a greater rate if required during takeoff or maneuvering

flight.

Figure 16. Power Loading vs. Disk Loading for the Vertical Thrust Configuration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-14-320.jpg)

![16

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

The optimum figure of merit of the Paparazzi

UAS was assumed to be the minimum optimal value

of 0.7 in order to be conservative and allow extra

room in possible losses or future changes in the

design which might have an effect on the overall

performance of the vehicle. Once the figure of merit

was defined, the power requirements to takeoff and

hover were calculated. The disk loading required to

hover was estimated to be 2.33 psf, and it was

determined that each motor had to produce 0.106 hp

to hover, resulting in a total power required of 0.351

hp. Note that an extra 10% was added to the total

power result in order to account for potential drag

and transmission losses.

Since the power required to hover is a

representation of the minimum amount of power

required to maintain the UAS in a fixed equilibrium

position with the environment, the power required to

climb was estimated by using the conservation of energy relationship.

(16)

[ √( ) ] (17)

Then, to find the total power required to climb to the minimum transition height of 20 feet, it was necessary to

assume a suitable Vc of 180 fpm, and the total power required to takeoff was computed to be 0.42 hp.

H. Stability

The first approach towards determining the stability conditions of the aircraft was followed by making a more

precise estimation of the center of gravity’s location. In order to find the location of the CG, every component

included in the vehicle was considered as a point mass with a defined weight and location; then, the CG equation

yielded,

∑ ∑

(18)

In order to use the equation above, the point mass locations of the wings, fuselage, tail, and spars were found by

calculating the moment of area of the surfaces and dividing by its mass:

(19)

From the equations above, the CG location was calculated to be 4.0 inches from the leading edge. This was set

constant to be at the location of rotation for transition. From the aerodynamic analysis the wing’s aerodynamic

center was found to be located 4.36 inches aft the rectangular section leading edge as computed. A 2D

representation of the location of each point mass, the CG location, and the NP location was developed as a visual

representation.

Figure 18. Power and Disc Loading for Figures of Merit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-17-320.jpg)

![42

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

0.61454 -0.00262 0.5 -0.03978

0.671 0.00085 0.56526 -0.03638

0.72557 0.00378 0.62941 -0.03247

0.77737 0.00601 0.69134 -0.02823

0.82556 0.00742 0.75 -0.02384

0.86933 0.00793 0.80438 -0.01945

0.90792 0.00757 0.85355 -0.01522

0.94063 0.00634 0.89668 -0.01127

0.96666 0.00442 0.93301 -0.0077

0.9853 0.0023 0.96194 -0.00463

0.99635 0.00063 0.98296 -0.00218

1 0 0.99572 -0.00057

1 0

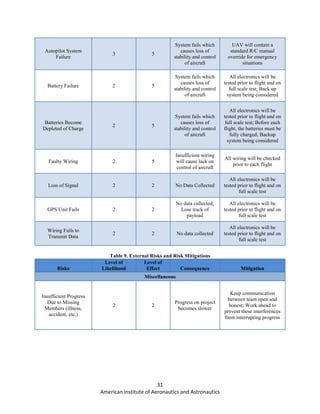

Appendix VIII—Wind Tunnel Data Reduction

%% Wind Tunnel Analysis

%Team Paparazzi

clear

clc

%% Conversion Factors

% < < Distance > >

nm_2_miles = 1.15078; %multiply to convert from nm to miles

miles_2_ft = 5280; %multiply to convert from miles to feet

in_2_ft = 1/12; %multiply to convert from in to ft

% < < Speed > >

kts_2_mph = 1.1508; %multiply to convert from kts to mph

kts_2_fps = 1.6878; %multiply to convert from kts to fps

mph_2_fps = 1.46667; %multiply to convert from mph to fps

% < < Mass > >

oz_2_lbs = 1/16; %multiply to convert from oz to lbs

% < < Temperature > >

fah_2_rank = 460.67; %add to convert from Fahrenheit to Rankine

% < < Pressure > >

inHg_2_psf = 70.7262; %multiply to convert from inches Mercury

to Psf

% < < Time > >

hour_2_sec = 3600; %multiply to convert from hours to seconds

min_2_sec = 60; %multiply to convert from min to seconds

% < < Angles > >

deg_2_rad = pi/180; %multiply to convert from degrees to radians

%% Atmospheric Conditions

Tatm = 76; %Fahrenheit

Tatm = Tatm + fah_2_rank; %Convert to working units

Patm = 29.5; %inches of Mercury

Patm = Patm*inHg_2_psf; %Convert to working units

Rair = 1716; %Air Constant in engineering units

Density = Patm/(Rair*Tatm); %Air Density at Given Conditions

mu = (3.62*10^-

7)*((Tatm/518.7)^1.5)*((518.7+198.72)/(Tatm+198.72));

%air viscocity in engineering units at Patm and Tatm

%-> Got equation from Introduction to Flight 7th ed.

nu = mu/Density;

a_SL = 1116; %Speed of Sound at SL in fps

%% Chosen Testing Variables

Vvec = [0 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 60 92]; %Wind Tunnel Speeds in

mph

Vvec = Vvec*mph_2_fps; %Convert to working units

q_s = 0.5*Density*Vvec.^2; %Uncorrected Dynamic Pressure

Vector

%% Wind Tunnel Test Section Geometry

H = 28; %Test Section Height in inches

H = H*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

B = 40; %Test Section Width in inches

B = B*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

Lts = 54; %Test Section Length in inches

Lts = Lts*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

Acs = H*B; %Test Section Cross-sectional (Frontal) Area

Ats = H*Lts; %Test Section Area

Strut_D = 1.5; %Strut Diameter in inches <<NOT UPDATED>>

Strut_D = Strut_D*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

Strut_L = 15; %Strut Length in inches <<NOT UPDATED>>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-43-320.jpg)

![43

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Strut_L = Strut_L*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

Astrut = Strut_D*Strut_L; %THis is the Area in contact with free

stream

%% Paparazzi Aircraft Wind Tunnel Model Geometry

% < < Wing > >

bw = 20; %Wing Span in inches

bw = bw*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

cbar_w = 4.25; %Wing MAC in inches

cbar_w = cbar_w*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

Sw = bw*cbar_w; %Wing Area

ARw = (bw^2)/Sw; %Wing Aspect Ratio

Vol_w = 31.29; %Wing Volume in inches cube

Vol_w = Vol_w*(in_2_ft^3); %Convert to working units

X_CG = 2; %CG location from wing LE in inches

X_CG = X_CG*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

tw = 0.1305*cbar_w; %Wing Thickness

Rew = (Vvec*cbar_w)/nu; %Wing Reynolds Number Vector

% < < Tail > >

bt = 10.63; %Tail Span in inches

bt = bt*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

cbar_t = 3.25; %Tail MAC in inches

cbar_t = cbar_t*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

St = bt*cbar_t; %Tail Area

ARt = (bt^2)/St; %Tail Aspect Ratio

lt = 7.5; %Distance from CG to Tail Aerodynamic Center (@ c/4)

in inches

lt = lt*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

V_H = (lt*St)/(cbar_w*Sw); %Tail Volume Coefficient

Ret = (Vvec*cbar_t)/nu; %Tail Reynolds Number Vector

% < < Fuselage > >

Vol_f = 7.4668; %Fuselage Volume in inches cube

Vol_f = Vol_f*(in_2_ft^3); %Convert to working units

X_balance_CG = 0.94; %X-Distance between Balance and

Aircraft CG in inches

X_balance_CG = X_balance_CG*in_2_ft; %Convert to working

units

Z_balance_CG = 0.50; %Z-Distance between Balance and Aircraft

CG in inches

Z_balance_CG = Z_balance_CG*in_2_ft; %Convert to working

units

D_f = 1.5; %Fuselage Diameter in inches

D_f = D_f*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

L_f = 6.875; %Fuselage Length in inches

L_f = L_f*in_2_ft; %Convert to working units

%% Figure Parameters

% < < Figure 6.23 > >

% Read from ARw and Taper Ratio = 1

bv_b = 0.86; %Get

% < < Figure 6.29 > >

bv = bv_b*bw;

be = (bw + bv)*0.5;

K = be/B;

be_B = be/B; %Read and Taper Ratio = 1

Delta = 0.146; %Get

% < < Figure 6.52 > >

lt_B = lt/B; %Read and Taper Ratio = 1

Tau2 = 0.35; %Get

% < < Figure 6.13 > >

tw_cbarw = tw/cbar_w; %Read (Airfoil not in the chart,

approximated)

Df_Lf = D_f/L_f; %Read

K1 = 0.997; %Get

K3 = 0.95; %Get

% < < Figure 6.14 > >

b2_B = 2*bw/B; %Read

B_H = B/H; %Read

Tau1 = 0.9125; %Get

%% Constant Correction Coefficients

Esbw = (K1*Tau1*Vol_w)/(Acs^(3/2));

EsbB = (K3*Tau1*Vol_f)/(Acs^(3/2));

Esbt = Esbw+EsbB;

Estrut_windshield = 0.25*(Acs/Ats);

DCmcg_Ddelta = -0.0626*V_H; %Assuming

%% Wind Tunnel Test

%% No Wind with Model Data

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('no_wind.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-44-320.jpg)

![44

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_no_wind = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_no_wind = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_no_wind = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_no_wind = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Side_no_wind = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_no_wind = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment Vector

in lbs*ft

Yaw_no_wind = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%% No Model with Wind at 92 mph Data

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data]= importfile('no_model_92mph.dat', 2);

alpha_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_no_model_92mph = Data(1:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%To correct Cruise conditions besides 92 mph, we need to

nondimensionalize the Data

%Divide Loads by 0.5*Density*V^2*Sstruts

%Divide Moments by 0.5*Density*V^2*Sstruts*Dstrut

CLs_no_model =

Lift_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut);

CDs_no_model =

Drag_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut);

CSFs_no_model =

Side_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut);

CMs_no_model =

Pitch_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut*Stru

t_D);

CLRs_no_model =

Roll_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut*Strut

_D);

CNs_no_model =

Yaw_no_model_92mph/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end)^2)*Astrut*Strut

_D);

%% Cruise Analysis:

%% < < Speed = 30 mph > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('cruise_30mph.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Side_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_cruise_30mph = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_cruise_30mph_corr = Lift_cruise_30mph - Lift_no_wind;

Drag_cruise_30mph_corr = Drag_cruise_30mph - Drag_no_wind;

Pitch_cruise_30mph_corr = Pitch_cruise_30mph - Pitch_no_wind;

Side_cruise_30mph_corr = Side_cruise_30mph - Side_no_wind;

Roll_cruise_30mph_corr = Roll_cruise_30mph - Roll_no_wind;

Yaw_cruise_30mph_corr = Yaw_cruise_30mph - Yaw_no_wind;

%Now, Since V is not 92 mph, we nondimensionalize Lift and

Drag

%To correct for no model in Lift and Drag to find other correction

factors

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Lift_cruise_30mph_corr/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(5)^2)*Sw);

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Drag_cruise_30mph_corr/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(5)^2)*Sw);

%Now we correct for no model error

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr = CLs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr = CDs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CDs_no_model;

%Now we compute CL squared to find K and CD0

CLs_cruise_30mph_CG_sq = CLs_cruise_30mph_corr.^2;

%{

%We plot to have a sense of the results (Should be a straigth line)

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_30mph_CG_sq,CDs_cruise_30mph_corr)

%}

%We do a linear fit to compute the slope and the CD intercept

(CD0)

CL_sq_CD_30mph_Eq =

polyfit(CLs_cruise_30mph_CG_sq,CDs_cruise_30mph_corr,1);

%Compute K

K_cruise_30mph = CL_sq_CD_30mph_Eq(1);

%Compute e

e_osw_cruise_30mph = 1/(K_cruise_30mph*ARw*pi);

%Compute CD0

CD0_cruise_30mph = CL_sq_CD_30mph_Eq(2);

%Find Missing correction factors

Ewbt_cruise_30mph = (Sw/(4*Acs))*CD0_cruise_30mph;

Etot_cruise_30mph = Esbt + Ewbt_cruise_30mph +

Estrut_windshield;

%Compute Corrected dynamic pressure

q_corr_cruise_30mph = q_s(5)*(1+Etot_cruise_30mph)^2;

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Lift_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Drag_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-45-320.jpg)

![45

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Side_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Pitch_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Roll_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_cruise_30mph_corr =

Yaw_cruise_30mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr = CLs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr = CDs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr = CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_cruise_30mph_corr = CMs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr = CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_cruise_30mph_corr = CNs_cruise_30mph_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_cruise_30mph =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_cruise_30mph_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_cruise_30mph_corr = alpha_cruise_30mph +

Delta_alpha_cruise_30mph;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_cruise_30mph =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_cruise_30mph_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_cruise_30mph =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance +- Loads*distance

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = CLs_cruise_30mph_corr;

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = CDs_cruise_30mph_corr +

Delta_Cd_cruise_30mph;

CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr;

CMs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = (CMs_cruise_30mph_corr +...

CLs_cruise_30mph_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_cruise_30mph_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_cruise_30mph;

CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr -...

CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG = CNs_cruise_30mph_corr +...

CSFs_cruise_30mph_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%{

%Plot Results for further Study

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_30mph_corr,CLs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG)

title('Lift Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 30mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_L')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG,CDs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG)

title('Drag Polar at 30mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_D')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG,CMs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG)

title('Moment Coefficient vs. Lift Coefficient at 30mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_m about CG')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_30mph_corr,CLRs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG)

title('Rolling Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 30mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_Lroll')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_30mph_corr,CNs_cruise_30mph_corr_CG)

title('Yawing Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 30mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_N')

%}

%% < < Speed = 60 mph > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('cruise_60mph.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Side_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_cruise_60mph = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_cruise_60mph_corr = Lift_cruise_60mph - Lift_no_wind;

Drag_cruise_60mph_corr = Drag_cruise_60mph - Drag_no_wind;

Pitch_cruise_60mph_corr = Pitch_cruise_60mph - Pitch_no_wind;

Side_cruise_60mph_corr = Side_cruise_60mph - Side_no_wind;

Roll_cruise_60mph_corr = Roll_cruise_60mph - Roll_no_wind;

Yaw_cruise_60mph_corr = Yaw_cruise_60mph - Yaw_no_wind;

%Now, Since V is not 92 mph, we nondimensionalize Lift and

Drag

%To correct for no model in Lift and Drag to find other correction

factors

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Lift_cruise_60mph_corr/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end-1)^2)*Sw);

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Drag_cruise_60mph_corr/(0.5*Density*(Vvec(end-1)^2)*Sw);

%Now we correct for no model error

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr = CLs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr = CDs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CDs_no_model;

%Now we compute CL squared to find K and CD0

CLs_cruise_60mph_CG_sq = CLs_cruise_60mph_corr.^2;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-46-320.jpg)

![46

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

%{

%We plot to have a sense of the results (Should be a straigth line)

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_60mph_CG_sq,CDs_cruise_60mph_corr)

%}

%We do a linear fit to compute the slope and the CD intercept

(CD0)

CL_sq_CD_60mph_Eq =

polyfit(CLs_cruise_60mph_CG_sq,CDs_cruise_60mph_corr,1);

%Compute K

K_cruise_60mph = CL_sq_CD_60mph_Eq(1);

%Compute e

e_osw_cruise_60mph = 1/(K_cruise_60mph*ARw*pi);

%Compute CD0

CD0_cruise_60mph = CL_sq_CD_60mph_Eq(2);

%Find Missing correction factors

Ewbt_cruise_60mph = (Sw/(4*Acs))*CD0_cruise_60mph;

Etot_cruise_60mph = Esbt + Ewbt_cruise_60mph +

Estrut_windshield;

%Compute Corrected dynamic pressure

q_corr_cruise_60mph = q_s(end-1)*(1+Etot_cruise_60mph)^2;

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Lift_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw);

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Drag_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw);

CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Side_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw);

CMs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Pitch_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Roll_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_cruise_60mph_corr =

Yaw_cruise_60mph_corr/(q_corr_cruise_60mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr = CLs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr = CDs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr = CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_cruise_60mph_corr = CMs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr = CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_cruise_60mph_corr = CNs_cruise_60mph_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_cruise_60mph =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_cruise_60mph_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_cruise_60mph_corr = alpha_cruise_60mph +

Delta_alpha_cruise_60mph;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_cruise_60mph =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_cruise_60mph_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_cruise_60mph =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = CLs_cruise_60mph_corr;

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = CDs_cruise_60mph_corr +

Delta_Cd_cruise_60mph;

CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr;

CMs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = (CMs_cruise_60mph_corr +...

CLs_cruise_60mph_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_cruise_60mph_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_cruise_60mph;

CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr -...

CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG = CNs_cruise_60mph_corr +...

CSFs_cruise_60mph_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%{

%Plot Results for further Study

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_60mph_corr,CLs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG)

title('Lift Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 60mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_L')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG,CDs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG)

title('Drag Polar at 60mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_D')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG,CMs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG)

title('Moment Coefficient vs. Lift Coefficient at 60mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_m')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_60mph_corr,CLRs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG)

title('Rolling Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 60mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_Lroll')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_60mph_corr,CNs_cruise_60mph_corr_CG)

title('Yawing Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 60mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_N')

%}

%% < < Speed = 92 mph (Design Speed) > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('cruise_92mph.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_cruise_92mph = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_cruise_92mph = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_cruise_92mph = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_cruise_92mph = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-47-320.jpg)

![48

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

%{%}

%Plot Results for further Study

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CLs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'Line

Width',2)

hold on

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CL_alpha_cruise_92mph_Eq,'--

k','Linewidth',2)

title('Lift Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 92mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_L')

legend('Wind Tunnel Result','Linear Fit','location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,CDs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'L

ineWidth',2)

title('Drag Polar at 92mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_D')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CMs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'b','L

ineWidth',2)

hold on

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CM_cruise_92mph_alpha_Eq,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_m')

legend('Wind Tunnel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(CLs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,CMs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'

b','LineWidth',2)

hold on

plot(CLs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,CM_cruise_92mph_CL_Eq,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Moment Coefficient vs. Lift Coefficient at 92mph')

xlabel('C_L')

ylabel('C_m')

legend('Wind Tunnel Result','LinearFit','location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CLRs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'Lin

eWidth',2)

title('Rolling Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 92mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_Lroll')

figure

plot(alpha_cruise_92mph_corr,CNs_cruise_92mph_corr_CG,'Line

Width',2)

title('Yawing Moment Coefficient vs. Angle of Attack at 92mph')

xlabel('Angle of Attack (Degrees)')

ylabel('C_N')

%% Zero Reference for Stability Analysis

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('zero_reference_control.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in

Deg.

Lift_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in

lbs.

Pitch_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector

in lbs

Roll_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_zero_reference_control = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_zero_reference_control_corr = Lift_zero_reference_control -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_zero_reference_control_corr = Drag_zero_reference_control

- Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_zero_reference_control_corr = Pitch_zero_reference_control

- Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_zero_reference_control_corr = Side_zero_reference_control -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_zero_reference_control_corr = Roll_zero_reference_control -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_zero_reference_control_corr = Yaw_zero_reference_control

- Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Lift_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Drag_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Side_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Pitch_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cba

r_w);

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Roll_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar

_w);

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr =

Yaw_zero_reference_control_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cba

r_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr - CLs_no_model;

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr - CDs_no_model;

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr - CSFs_no_model;

CMs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CMs_zero_reference_control_corr - CMs_no_model;

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr - CLRs_no_model;

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr =

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr - CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_zero_reference_control =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_zero_reference_control_

corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_zero_reference_control_corr =

alpha_zero_reference_control +

Delta_alpha_zero_reference_control;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_zero_reference_control =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_zero_reference_control_corr.^2);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-49-320.jpg)

![49

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_zero_reference_control =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr;

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr +

Delta_Cd_zero_reference_control;

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr;

CMs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

(CMs_zero_reference_control_corr +...

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_zero_reference_control_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_zero_reference_control;

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr -...

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG =

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr +...

CSFs_zero_reference_control_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%% Roll Body Stability Analysis

%% < < Left Wing 11 Degrees Down > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('roll_left_wing_11deg_down.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_roll_11deg_down = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_roll_11deg_down_corr = Lift_roll_11deg_down -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_roll_11deg_down_corr = Drag_roll_11deg_down -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_roll_11deg_down_corr = Pitch_roll_11deg_down -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_roll_11deg_down_corr = Side_roll_11deg_down -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_roll_11deg_down_corr = Roll_roll_11deg_down -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_roll_11deg_down_corr = Yaw_roll_11deg_down -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Lift_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Drag_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Side_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Pitch_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Roll_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr =

Yaw_roll_11deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CMs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr = CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_roll_11deg_down =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_roll_11deg_down_corr = alpha_roll_11deg_down +

Delta_alpha_roll_11deg_down;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_roll_11deg_down =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_11deg_down =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr;

CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr +

Delta_Cd_roll_11deg_down;

CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr;

CMs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = (CMs_roll_11deg_down_corr

+...

CLs_roll_11deg_down_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_roll_11deg_down_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_11deg_down;

CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr

-...

CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG = CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr

+...

CSFs_roll_11deg_down_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%% < < Left Wing 8 Degrees Up > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('roll_left_wing_8deg_up.dat', 2);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-50-320.jpg)

![50

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Side_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_roll_8deg_up = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_roll_8deg_up_corr = Lift_roll_8deg_up - Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_roll_8deg_up_corr = Drag_roll_8deg_up -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_roll_8deg_up_corr = Pitch_roll_8deg_up -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_roll_8deg_up_corr = Side_roll_8deg_up - Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_roll_8deg_up_corr = Roll_roll_8deg_up - Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_roll_8deg_up_corr = Yaw_roll_8deg_up - Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Lift_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Drag_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Side_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Pitch_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Roll_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr =

Yaw_roll_8deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CMs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr = CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_roll_8deg_up =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_roll_8deg_up_corr = alpha_roll_8deg_up +

Delta_alpha_roll_8deg_up;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_roll_8deg_up =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_8deg_up =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr;

CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr +

Delta_Cd_roll_8deg_up;

CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr;

CMs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = (CMs_roll_8deg_up_corr +...

CLs_roll_8deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_roll_8deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_8deg_up;

CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr -...

CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG = CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr +...

CSFs_roll_8deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%% < < Left Wing 16 Degrees Up > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('roll_left_wing_16deg_up.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Side_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_roll_16deg_up = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_roll_16deg_up_corr = Lift_roll_16deg_up - Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_roll_16deg_up_corr = Drag_roll_16deg_up -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_roll_16deg_up_corr = Pitch_roll_16deg_up -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_roll_16deg_up_corr = Side_roll_16deg_up -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_roll_16deg_up_corr = Roll_roll_16deg_up -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_roll_16deg_up_corr = Yaw_roll_16deg_up -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Lift_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Drag_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Side_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Pitch_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Roll_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr =

Yaw_roll_16deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-51-320.jpg)

![51

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CMs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr = CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_roll_16deg_up =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_roll_16deg_up_corr = alpha_roll_16deg_up +

Delta_alpha_roll_16deg_up;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_roll_16deg_up =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_16deg_up =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr;

CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr +

Delta_Cd_roll_16deg_up;

CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr;

CMs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = (CMs_roll_16deg_up_corr +...

CLs_roll_16deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_roll_16deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_roll_16deg_up;

CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr -...

CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG = CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr +...

CSFs_roll_16deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CLRs_wing_incidence = [CLRs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG...

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CLRs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG...

CLRs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG];

CNs_wing_incidence = [CNs_roll_11deg_down_corr_CG...

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CNs_roll_8deg_up_corr_CG...

CNs_roll_16deg_up_corr_CG];

Wing_incidence_angles = [-11 0 8 16];

CLR_Wing_incidence_fit =

polyfit(Wing_incidence_angles,CLRs_wing_incidence,1);

CN_Wing_incidecne_fit =

polyfit(Wing_incidence_angles,CNs_wing_incidence,1);

CLRs_Equation_incidence =

polyval(CLR_Wing_incidence_fit,Wing_incidence_angles);

CNs_Equation_incidence =

polyval(CN_Wing_incidecne_fit,Wing_incidence_angles);

%Compute Stability Derivative

DCLroll_Di = CLR_Wing_incidence_fit(1); %1/deg

DCN_Di = CN_Wing_incidecne_fit(1); %SHould be negative, it is

positive probably due to decrease in Drag as AoA increases!!

%{%}

figure

plot(Wing_incidence_angles,CLRs_wing_incidence,'b','LineWidth'

,2)

hold on

plot(Wing_incidence_angles,CLRs_Equation_incidence,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Rolling Moment Coefficient vs. Wing Incidence Angle')

xlabel('Wing Incidence Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_Lroll')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(Wing_incidence_angles,CNs_wing_incidence,'b','LineWidth',

2)

hold on

plot(Wing_incidence_angles,CNs_Equation_incidence,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Yawing Moment Coefficient vs. Wing Incidence Angle')

xlabel('Wing Incidence Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_N')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

%% Yaw Body Stability Analysis

% < < Sideslip = 8 Deg. Counterclockwise > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('yaw_8deg_counterclockwise.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in

lbs

Roll_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_yaw_8deg_counter = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Lift_yaw_8deg_counter -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Drag_yaw_8deg_counter -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Pitch_yaw_8deg_counter -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Side_yaw_8deg_counter -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Roll_yaw_8deg_counter -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = Yaw_yaw_8deg_counter -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Lift_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-52-320.jpg)

![52

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Drag_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Side_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Pitch_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w

);

CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Roll_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w)

;

CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr =

Yaw_yaw_8deg_counter_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w

);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CMs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_yaw_8deg_counter =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr

;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_yaw_8deg_counter_corr = alpha_yaw_8deg_counter +

Delta_alpha_yaw_8deg_counter;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_yaw_8deg_counter =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_yaw_8deg_counter =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG =

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr;

CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG = CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr

+ Delta_Cd_yaw_8deg_counter;

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG =

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr;

CMs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG =

(CMs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr +...

CLs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_yaw_8deg_counter;

CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG =

CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr -...

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG = CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr

+...

CSFs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

% < < Sideslip = 9 Deg. clockwise > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('yaw_9deg_clockwise.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in

lbs

Roll_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_yaw_9deg_colockw = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Lift_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Drag_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Pitch_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Side_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Roll_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = Yaw_yaw_9deg_colockw -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Lift_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Drag_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Side_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Pitch_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_

w);

CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Roll_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w

);

CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr =

Yaw_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_

w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr

- CSFs_no_model;

CMs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CMs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr

- CLRs_no_model;

CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-53-320.jpg)

![53

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Delta_alpha_yaw_9deg_colockw =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_cor

r;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr = alpha_yaw_9deg_colockw +

Delta_alpha_yaw_9deg_colockw;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_yaw_9deg_colockw =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_yaw_9deg_colockw =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr;

CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr + Delta_Cd_yaw_9deg_colockw;

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr;

CMs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

(CMs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr +...

CLs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_yaw_9deg_colockw;

CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr -...

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG =

CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr +...

CSFs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_beta_sweep = [CNs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG...

CNs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CNs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG];

CLRs_beta_sweep = [CLRs_yaw_8deg_counter_corr_CG...

CLRs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CLRs_yaw_9deg_colockw_corr_CG];

beta_angles = [-8 0 9];

CN_beta_fit = polyfit(beta_angles,CNs_beta_sweep,1);

CLR_beta_fit = polyfit(beta_angles,CLRs_beta_sweep,1);

CLRs_Equation_beta = polyval(CLR_beta_fit,beta_angles);

CNs_Equation_beta = polyval(CN_beta_fit,beta_angles);

%Compute Stability Derivative

DCLroll_DBeta = CLR_beta_fit(1); %1/deg

DCN_DBeta = CN_beta_fit(1);

%{%}

figure

plot(beta_angles,CLRs_beta_sweep,'b','LineWidth',2)

hold on

plot(beta_angles,CLRs_Equation_beta,'--k','LineWidth',2)

title('Rolling Moment Coefficient vs. Sideslip Angle')

xlabel('Sideslip Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_Lroll')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(beta_angles,CNs_beta_sweep,'b','LineWidth',2)

hold on

plot(beta_angles,CNs_Equation_beta,'--k','LineWidth',2)

title('Yawing Moment Coefficient vs. Sideslip Angle')

xlabel('Sideslip Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_N')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

%% Pitch Body Stability Analysis

%% < < Tail 5 Degrees Down > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('pitch_5deg_down.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_pitch_5deg_down = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Lift_pitch_5deg_down -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Drag_pitch_5deg_down -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Pitch_pitch_5deg_down -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Side_pitch_5deg_down -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Roll_pitch_5deg_down -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_pitch_5deg_down_corr = Yaw_pitch_5deg_down -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Lift_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Drag_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Side_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Pitch_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w)

;

CLRs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Roll_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_pitch_5deg_down_corr =

Yaw_pitch_5deg_down_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CSFs_no_model;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-54-320.jpg)

![54

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CLRs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_pitch_5deg_down_corr = CNs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_pitch_5deg_down =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_pitch_5deg_down_corr = alpha_pitch_5deg_down +

Delta_alpha_pitch_5deg_down;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_pitch_5deg_down =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_pitch_5deg_down =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG = CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr;

CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG = CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr +

Delta_Cd_pitch_5deg_down;

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG =

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr;

CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG = (CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr

+...

CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)-...

CDs_pitch_5deg_down_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_pitch_5deg_down;

CLRs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG =

CLRs_pitch_5deg_down_corr -...

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG = CNs_pitch_5deg_down_corr

+...

CSFs_pitch_5deg_down_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

%% < < Tail 10 Degrees Up > >

%Import .dat File into Matlab

[Data,SizeData] = importfile('pitch_10deg_up.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_pitch_10deg_up = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

%First, we correct for no wind effect

Lift_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Lift_pitch_10deg_up -

Lift_no_wind(4);

Drag_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Drag_pitch_10deg_up -

Drag_no_wind(4);

Pitch_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Pitch_pitch_10deg_up -

Pitch_no_wind(4);

Side_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Side_pitch_10deg_up -

Side_no_wind(4);

Roll_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Roll_pitch_10deg_up -

Roll_no_wind(4);

Yaw_pitch_10deg_up_corr = Yaw_pitch_10deg_up -

Yaw_no_wind(4);

%Use Corrected dynamic pressure to compute all coefficients

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Lift_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Drag_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Side_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw);

CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Pitch_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CLRs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Roll_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

CNs_pitch_10deg_up_corr =

Yaw_pitch_10deg_up_corr/(q_corr_cruise_30mph*Sw*cbar_w);

%Now we correct all coefficients for no model error

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CLs_no_model;

CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CDs_no_model;

CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CSFs_no_model;

CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CMs_no_model;

CLRs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CLRs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CLRs_no_model;

CNs_pitch_10deg_up_corr = CNs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

CNs_no_model;

%Compute AoA correction Vector

Delta_alpha_pitch_10deg_up =

Delta*(1+Tau2)*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr;

%Corrected AoA

alpha_pitch_10deg_up_corr = alpha_pitch_10deg_up +

Delta_alpha_pitch_10deg_up;

%Drag Wall Correction

Delta_Cd_pitch_10deg_up =

Delta*(Sw/Acs)*(CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr.^2);

%Tail Moment Coefficient Correction Vector

Delta_Cm_CG_pitch_10deg_up =

DCmcg_Ddelta*(Sw/Acs)*(180/pi)*Delta*Tau2*...

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr;

%Now we translate the Loads and moments from Balance Center

to CG

%Loads_CG = Loads_Balance

%Moments_CG = Moment_Balance

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr;

CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr +

Delta_Cd_pitch_10deg_up;

CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr;

CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = (CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -...

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w)+...

CDs_pitch_10deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w)) -

Delta_Cm_CG_pitch_10deg_up;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-55-320.jpg)

![55

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CLRs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = CLRs_pitch_10deg_up_corr -

...

CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr*(Z_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CNs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG = CNs_pitch_10deg_up_corr +...

CSFs_pitch_10deg_up_corr*(X_balance_CG/cbar_w);

CLs_Tail_incidence_sweep = [CLs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG...

CLs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CLs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG];

CMs_Tail_incidence_sweep =

[CMs_pitch_5deg_down_corr_CG...

CMs_zero_reference_control_corr_CG...

CMs_pitch_10deg_up_corr_CG];

Tail_incidence_angles = [-5 0 10];

CM_tail_incidence_fit =

polyfit(Tail_incidence_angles,CMs_Tail_incidence_sweep,1);

CL_tail_incidence_fit =

polyfit(Tail_incidence_angles,CLs_Tail_incidence_sweep,1);

CLs_Equation_tail_incidence =

polyval(CL_tail_incidence_fit,Tail_incidence_angles);

CMs_Equation_tail_incidence =

polyval(CM_tail_incidence_fit,Tail_incidence_angles);

%Compute Stability Derivative

DCL_DTi = CL_tail_incidence_fit(1); %1/deg

DCM_DTi = CM_tail_incidence_fit(1); %1/deg

%{%}

figure

plot(Tail_incidence_angles,CLs_Tail_incidence_sweep,'b','LineWi

dth',2)

hold on

plot(Tail_incidence_angles,CLs_Equation_tail_incidence,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Lift Coefficient vs. Tail Incidence Angle')

xlabel('Tail Incidence Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_L')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

figure

plot(Tail_incidence_angles,CMs_Tail_incidence_sweep,'b','LineW

idth',2)

hold on

plot(Tail_incidence_angles,CMs_Equation_tail_incidence,'--

k','LineWidth',2)

title('Pitching Moment Coefficient vs. Sideslip Angle')

xlabel('Tail Incidence Angle (Deg.)')

ylabel('C_m')

legend('Wind Tunel Result','Linear Fit','Location','SouthEast')

%% Transition Analysis Data

% < < Wings 30 Degrees Up > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] =

importfile('transition_wing_30deg_up_0_20_30_35_40_45mph.dat

', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_transition_30deg = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

% < < Wings 60 Degrees Up > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] =

importfile('transition_wing_60deg_up_0_20_25_30_35.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_transition_60deg = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

% < < Wings 90 Degrees Up > >

%import .dat file to matlab

[Data,SizeData] =

importfile('transition_wing_90deg_up_0_15_20_25_30.dat', 2);

%Substract First Row which to substract Zero offset error

for i = 2:1:SizeData(1)

Data(i,:) = Data(i,:) - Data(1,:);

end

alpha_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,1); %AoA vector in Deg.

Lift_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,2); %Lift Vector in lbs.

Drag_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,3); %Drag Vector in lbs.

Pitch_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,4)*in_2_ft; %Pitching

Moment Vector in lbs*ft

Side_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,5); %Sideforce Vector in lbs

Roll_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,6)*in_2_ft; %Rolling Moment

Vector in lbs*ft

Yaw_transition_90deg = Data(2:end,7)*in_2_ft; %Yawing

Moment Vector in lbs*ft](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-56-320.jpg)

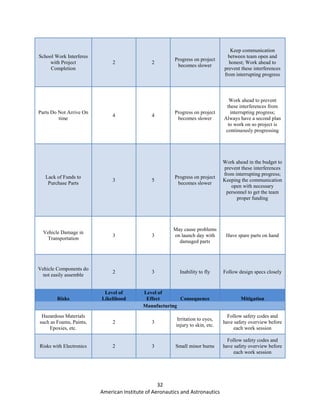

![61

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Appendix IX—Control Design

Longitundal

%Senior Design - Paparazzi

%Dynamic Stability and Feedback Control

clear

close all

%% Longitudinal State Space

%X(1) = udot

%X(2) = alphadot

%X(3) = thetadot (pitch)

%X(4) = qdot

%X(5) = hdot

% A = [ Xu/m Xw/m 0 -g...

% Zu/(m-Zwdot) Zw/(m-Zwdot) (Zq+m*U0)/(m-

Zwdot) 0...

% (Mu+Zu*Gamma)/Iyy (Mw+Zw*Gamma)/Iyy

((Mq+(Zq+m*U0))*Gamma)/Iyy 0...

% 0 0 1 0]

%B = [

%% Conversion Factors

y = 0.0107x - 0.4115

y = 0.0281x - 0.4924

y = 0.0457x - 0.4233

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0 5 10 15 20 25

Cm

Speed (kts)

30 Deg.

60 Deg.

90 Deg.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-62-320.jpg)

![62

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

% < < Distance > >

nm_2_miles = 1.15078; %multiply to convert from nm to miles

miles_2_ft = 5280; %multiply to convert from miles to feet

in_2_ft = 1/12; %multiply to convert from in to ft

% < < Speed > >

kts_2_mph = 1.1508; %multiply to convert from kts to mph

kts_2_fps = 1.6878; %multiply to convert from kts to fps

mph_2_fps = 1.46667; %multiply to convert from mph to fps

% < < Mass > >

oz_2_lbs = 1/16; %multiply to convert from oz to lbs

% < < Temperature > >

fah_2_rank = 460.67; %add to convert from Fahrenheit to Rankine

% < < Pressure > >

inHg_2_psf = 70.7262; %multiply to convert from inches Mercury

to Psf

% < < Time > >

hour_2_sec = 3600; %multiply to convert from hours to seconds

min_2_sec = 60; %multiply to convert from min to seconds

% < < Angles > >

deg_2_rad = pi/180; %multiply to convert from degrees to radians

%% Given Constant Atmospheric Data

P_SL = 2116.2; %psf

T_SL = 518.69; %Deg. Rankine

Rho_SL = 0.002377; %slugs/ft3

Gamma_Air = 1.4; %Constant

R_Air = 1716; %Air Constant

mu_Air = 3.7424*10^-7; %Air Constant

delta_STL = 0.9822;

theta_STL_STD = 0.997;

theta_STL_Cold = 0.784;

theta_STL_Hot = 1.0812;

delta_500_STL = 0.9692;

theta_500_STL_STD = 0.994;

theta_500_STL_Cold = 0.7972;

theta_500_STL_Hot = 1.0774;

sigma_500_STL = 0.975;

mu_500_STL = 3.72497*10^-7;

Tatm = T_SL*theta_STL_STD; %Rank

Rair = 1716;

g = 32.2; %gravity constant in ft/sec2

rho = 0.002377*sigma_500_STL; %Density at trim level

mu = (3.62*10^-

7)*((Tatm/518.7)^1.5)*((518.7+198.72)/(Tatm+198.72));

%air viscocity in engineering units at Patm and Tatm

%-> Got equation from Introduction to Flight 7th ed.

nu = mu/rho;

a_SL = 1116; %Speed of Sound at SL in fps

%% Vehicle Geometry

lH = 16.45; %inches

lH = lH*in_2_ft; %ft

cbar_w = 8.5; %in

cbar_w = cbar_w*in_2_ft;

cbar_H = 6.5;

cbar_H = cbar_H*in_2_ft;

alpha0H = 0;

bw = 40;

bw = bw*in_2_ft;

bH = 22;

bH = bH*in_2_ft;

Sw = bw*cbar_w; %Wing Planform Area

SH = bH*cbar_H;

ARw = (bw^2)/Sw;

ARH = (bH^2)/SH;

ht = lH/cbar_w;

hcg = (4*in_2_ft)/cbar_w;

VH = (SH*lH)/(Sw*cbar_w);

etaH = .9; %assumed due to propeller

influence

dTh = 0;

XdTh = 13.5;

XdTh = XdTh*in_2_ft;

M = 5.5/g; %mass of the vehicle

Imat = [4.214*10^6 1.4502*10^3 -2.5678*10^4;... %in

lbs*in^2

1.4502*10^3 4.215*10^6 3.563*10^4;...

-2.5678*10^4 3.563*10^4 2.5144*10^5];

Imat = Imat*(in_2_ft^2)/g; %in slugs*ft^2

Iyy = Imat(2,2); %slugs*ft^2

CD0 = 0.02385; %From Drag build-up Excel File

%% Trim Conditions

U0 = 40; %Trim Speed in fps

U0 = U0*kts_2_fps;

qinf = 0.5*rho*U0^2; %dynamic pressure at trim

qSM = qinf*Sw/M; %Constant in control derivatives

qSCIyy = qinf*Sw*cbar_w/Iyy;

CL0 = g/qSM; %Lift Coefficient at trim

ew = 4.61*(1-0.045*ARw^0.68)-3.1;

ewH = 4.61*(1-0.045*ARH^0.68)-3.1;

CDt = CD0 + (1/(pi*ARw*ew))*CL0^2;

TH_tot = CDt*qinf*Sw;

TH_mot = TH_tot/3;

alpha0 = 0;

Theta_T = 0;

Cm0 = 0.025;

iH = 1.94*deg_2_rad;

%% Stability Derivatives

CTh = TH_mot/(qinf*Sw);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b6d5ca9f-0cd8-4fef-be65-ca3bfedf9c4c-151130202313-lva1-app6891/85/Paparrazzi_Final-1-63-320.jpg)

![63

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

CD_alpha_fun = [0.04584 0.23491]; %1/rad

CD_alpha = polyval(CD_alpha_fun,alpha0);

CD_alphadot = 0.04584;

CLw_alpha = 4.58;

CLH_alpha = 4.12;

CLih = CLH_alpha*(etaH)*(SH/Sw);% + CTh; %Since we

are including (d/dih)(CTh*sin(ih)) which was approx as slope ih.

Cmih = -CLH_alpha*ht*etaH*(SH/Sw);

Cm_alphadot = -32.97; %From wind tunnel

analysis matlab

dE_dalpha = (2*CLw_alpha)/(pi*ARw);

CLH0 = CLH_alpha*(((1-dE_dalpha)*alpha0)+iH-alpha0H);

CDih = (2*CLH_alpha*CLH0*etaH*(SH/Sw))/(pi*ARH*ewH);

Cm_alpha = -0.2406; %1/rad

%Cm_alpha = -0.59;

%% Control Derivatives

Xu_Xpu = qSM*(-1*(((2/U0)*CD0)));

%Xalphadot = -qSM*CD_alphadot;

Xalphadot = 0;

Xalpha = qSM*(CL0-CD_alpha);

Xq = 0;

Xdih = -qSM*CDih;

XdT = qSCIyy*cos(Theta_T)/M;

Zu_Zpu = qSM*(-1*((2/U0)*CL0));

Zalpha = qSM*(CD0-CLw_alpha);

Zq = -VH*CLw_alpha;

Zalphadot = Zq*dE_dalpha;

Zih = -qSM*CLih;

ZdT = -sin(Theta_T)/M;

Mu_Mpu = qSCIyy*((2/U0)*Cm0);

Mq = Zq*hcg;

Malphadot = qSCIyy*Cm_alphadot;

Malpha_Mpalpha = -3.8657; %From Wind Tunnel

analysis 1/rad

Mih = .5*qinf*Sw*Cmih;

MdT = (dTh*cos(Theta_T) - XdTh*sin(Theta_T))/Iyy;

%% State Space

a11 = Xu_Xpu+((Xalphadot*(Zu_Zpu))/(U0-Zalphadot));

a12 = Xalpha+((Xalphadot*Zalpha)/(U0-Zalphadot));

a13 = -g;

a14 = Xq+(Xalphadot*((U0+Zq)/(U0-Zalphadot)));

a15 = 0;

a21 = ((Zu_Zpu)/(U0-Zalphadot));

a22 = Zalpha/(U0-Zalphadot);

a23 = 0;

a24 = ((U0+Zq)/(U0-Zalphadot));

a25 = 0;

a31 = 0;

a32 = 0;

a33 = 0;

a34 = 1;

a35 = 0;

a41 = Mu_Mpu + ((Malphadot*Zu_Zpu)/(U0-Zalphadot));