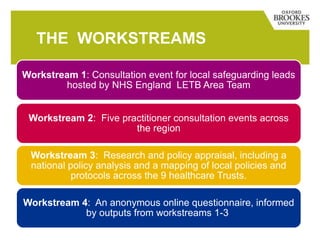

The document presents a regional audit exploring the knowledge and training needs of healthcare staff regarding child sexual exploitation (CSE) across nine NHS provider trusts and community healthcare settings. Key findings reveal significant gaps in understanding CSE, with many healthcare professionals inadequately trained and lacking access to necessary guidance. Recommendations include enhancing training on CSE prevention and implementing simplified communication pathways for accessing relevant protocols.