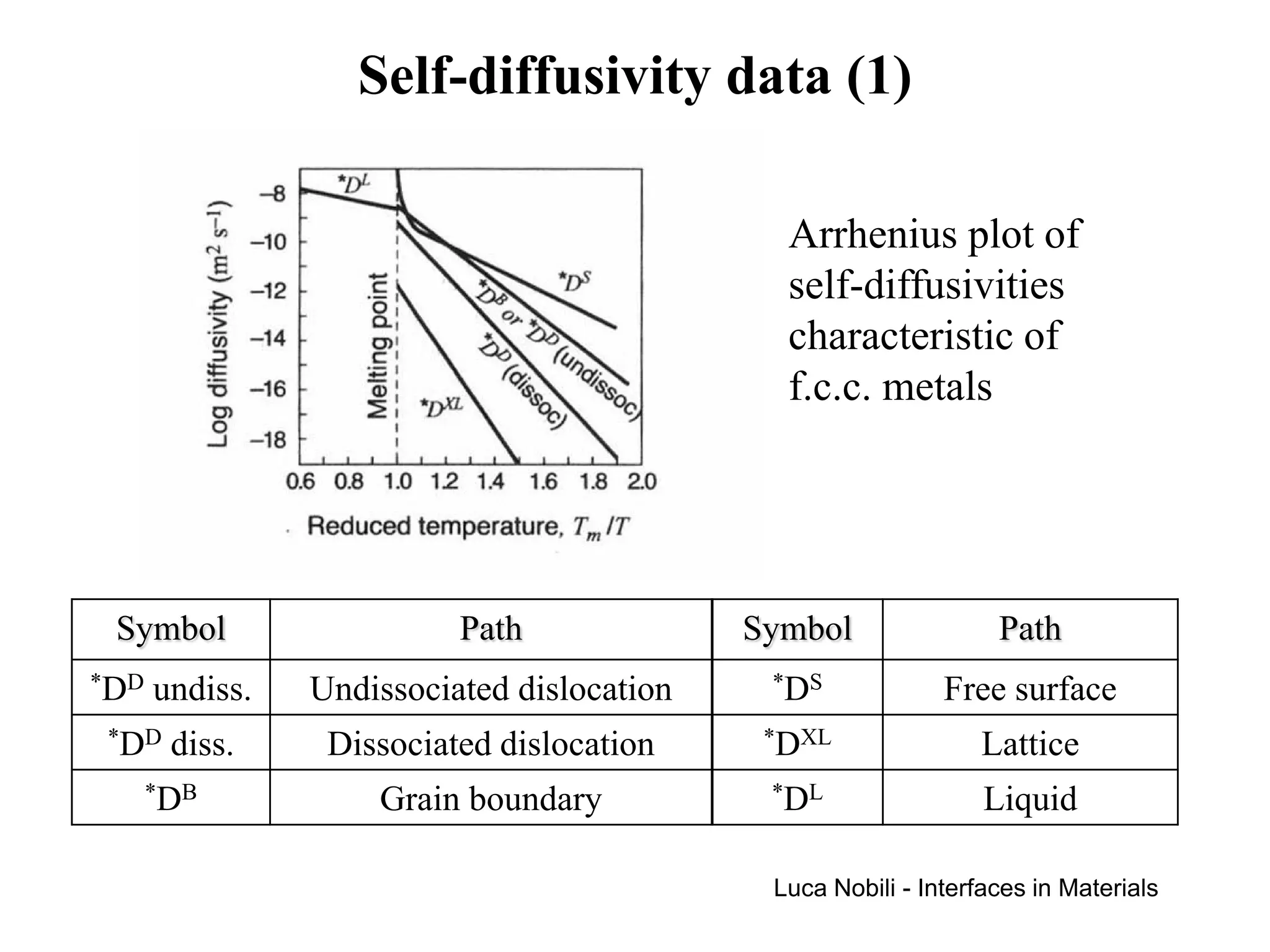

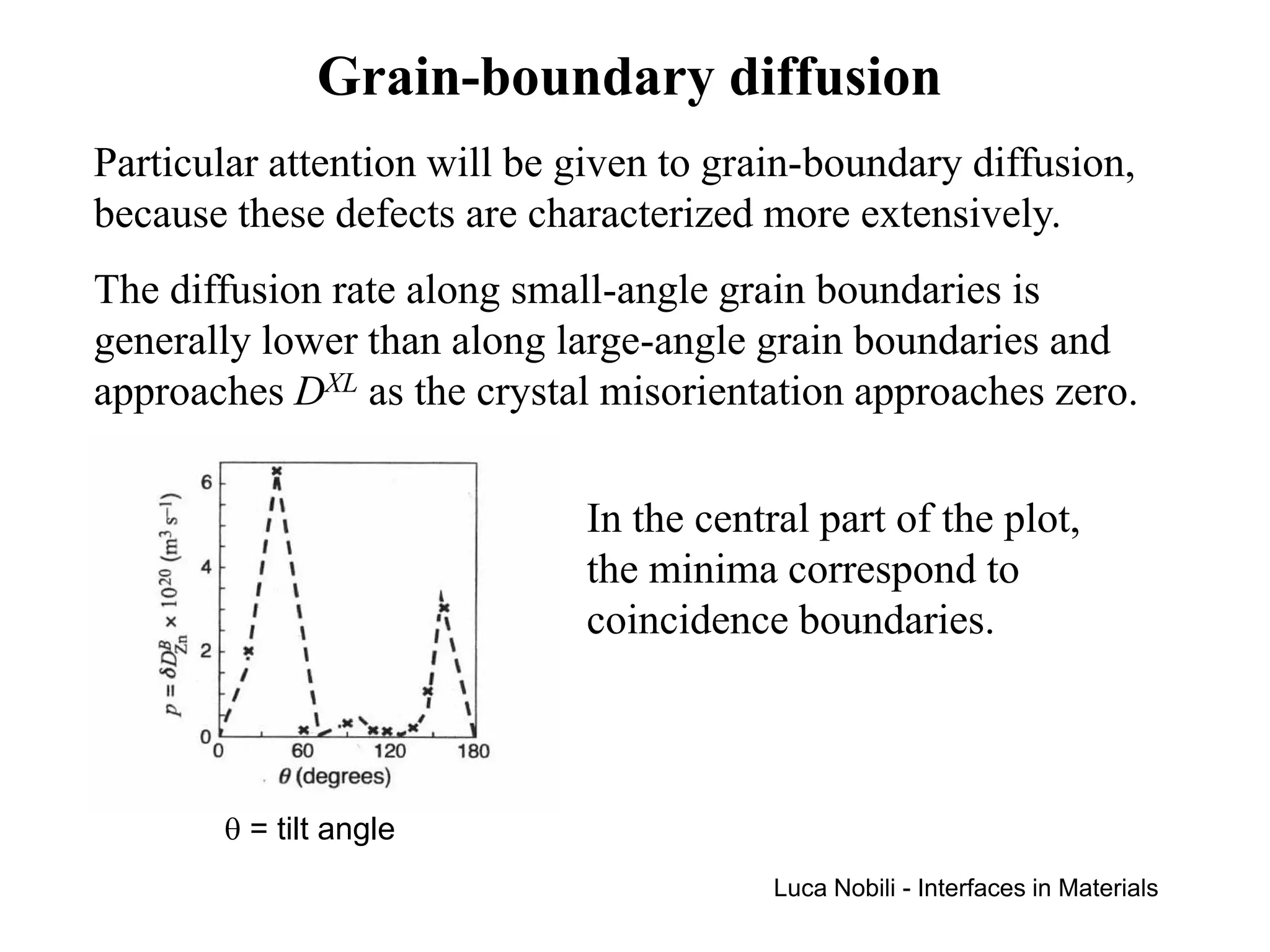

Diffusion rates can be orders of magnitude faster along interfaces like grain boundaries and dislocations compared to bulk crystals. This is due to faster diffusion occurring in a thin slab near the interface that contains disordered material. Diffusion in solids with interfaces can be modeled by replacing interfaces with thin slabs possessing much higher diffusivities. Self-diffusion data follows the trend that diffusion is fastest at free surfaces and slowest in the bulk lattice.

![Diffusion with moving interfaces (1)

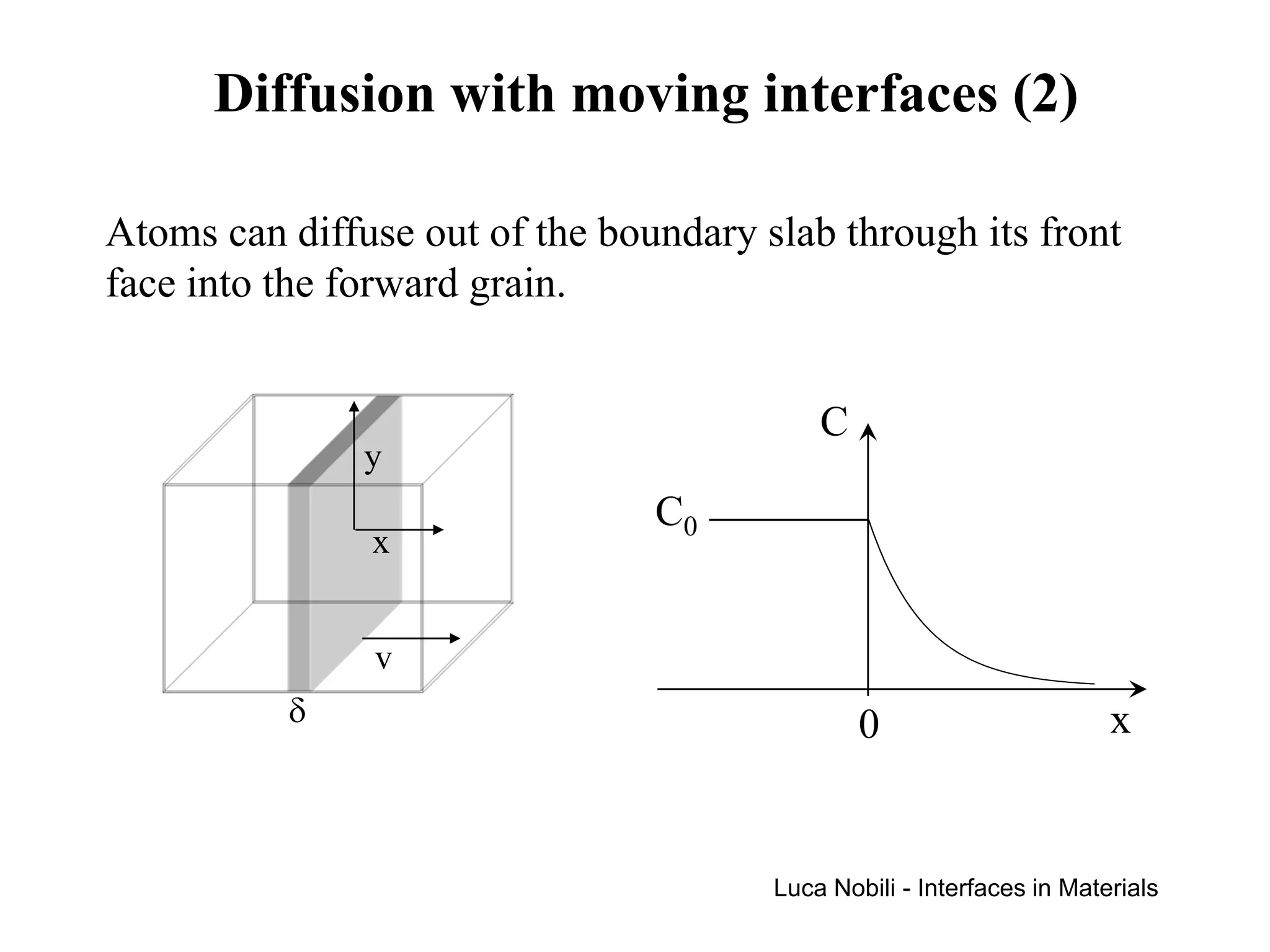

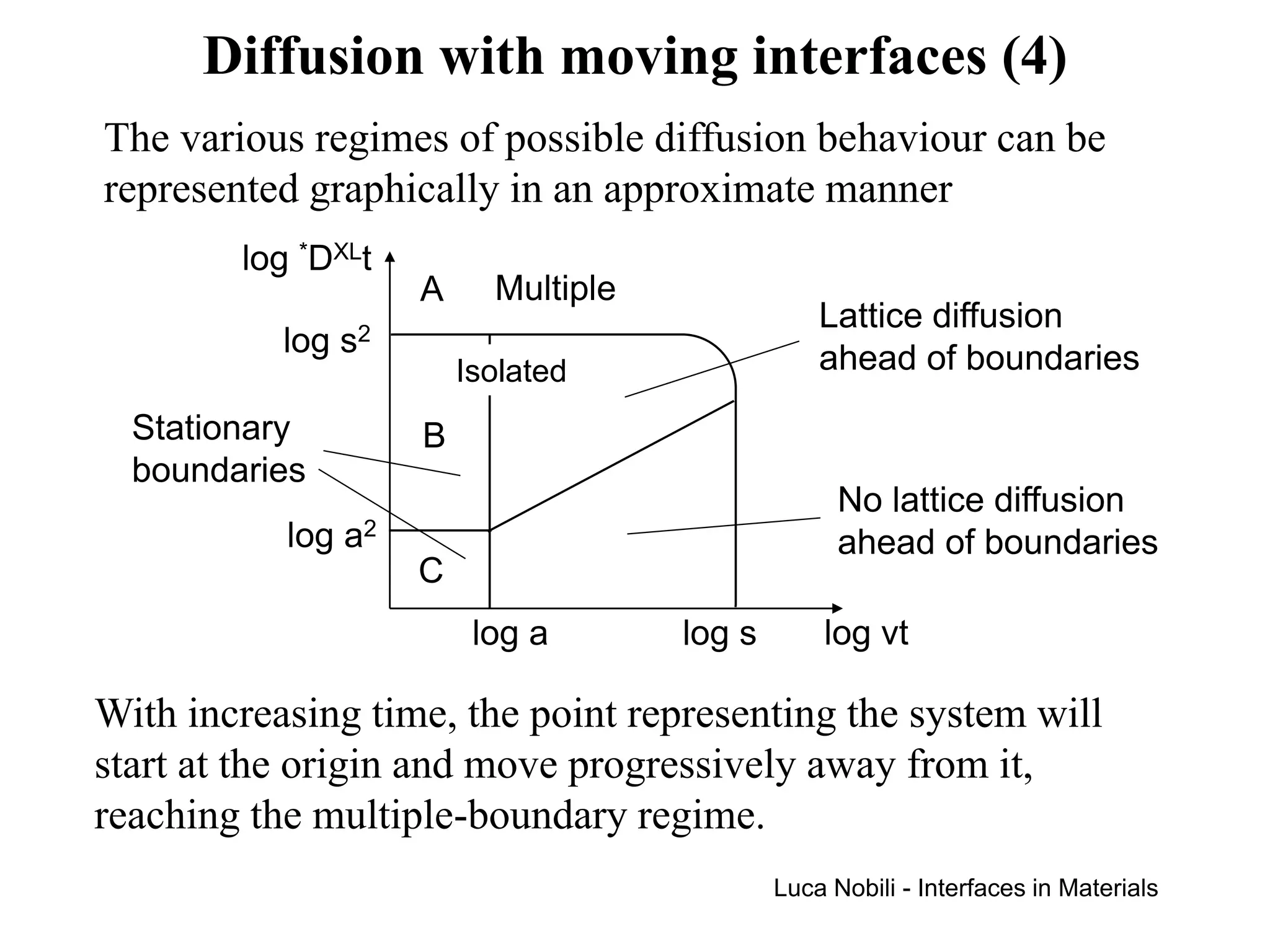

If v is the average boundary velocity, the boundaries will be

essentially stationary when v·t < a.

When the condition [(*DXLt)1/2 + v⋅t] > s is satisfied, the

multiple-boundary diffusion regime will exist.

When the condition [(*DXLt)1/2 + v⋅t] < s is satisfied, the

isolated-boundary diffusion regime will exist.

The isolated-boundary regime is subdivided into two regimes,

depending on whether the lattice diffusion is fast enough so that

the atoms are able to diffuse into the grains ahead of the

advancing boundaries.

Luca Nobili - Interfaces in Materials](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pdiffusion2-120311210421-phpapp02/75/P-diffusion_2-13-2048.jpg)

![Grain boundary self-diffusivity (1)

The effect of solute segregation on the grain boundary self-

diffusivity may be expressed by:

*

D B =*D B (0)[1 + (bl − α ⋅ β b ) ⋅ nl ]

*DB(0) grain boundary diffusivity in pure solvent

bl coefficient which relates lattice diffusivity and solvent fraction

βb enrichment ratio

nl atomic fraction of solute in the lattice

α coefficient depending on the size of the solvent (asv) and solute

(asu) atoms and the width of the grain boundary (δ = m⋅asv);

α = 2asv (m ⋅ asu )

2 2

Luca Nobili - Interfaces in Materials](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pdiffusion2-120311210421-phpapp02/75/P-diffusion_2-17-2048.jpg)