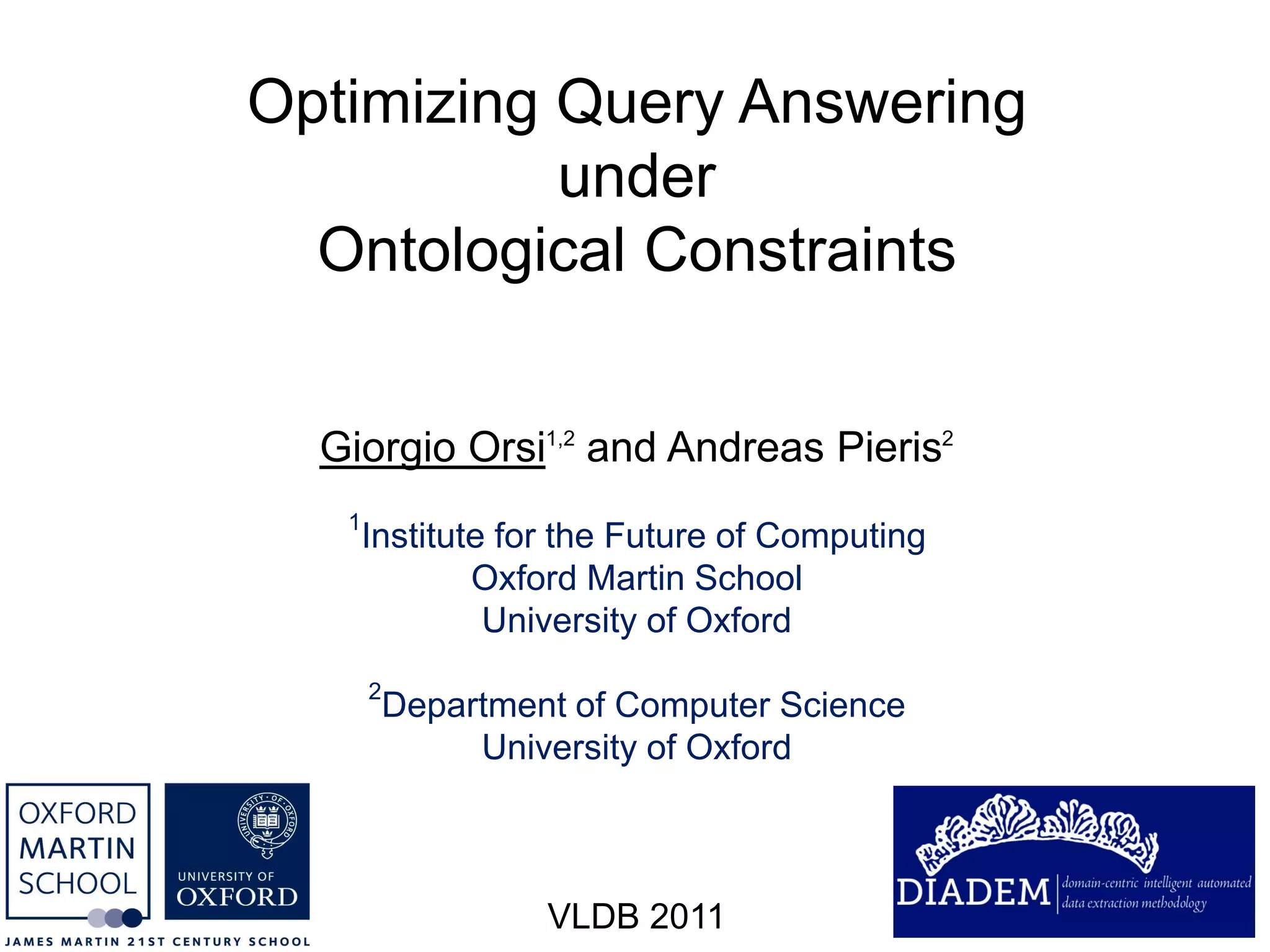

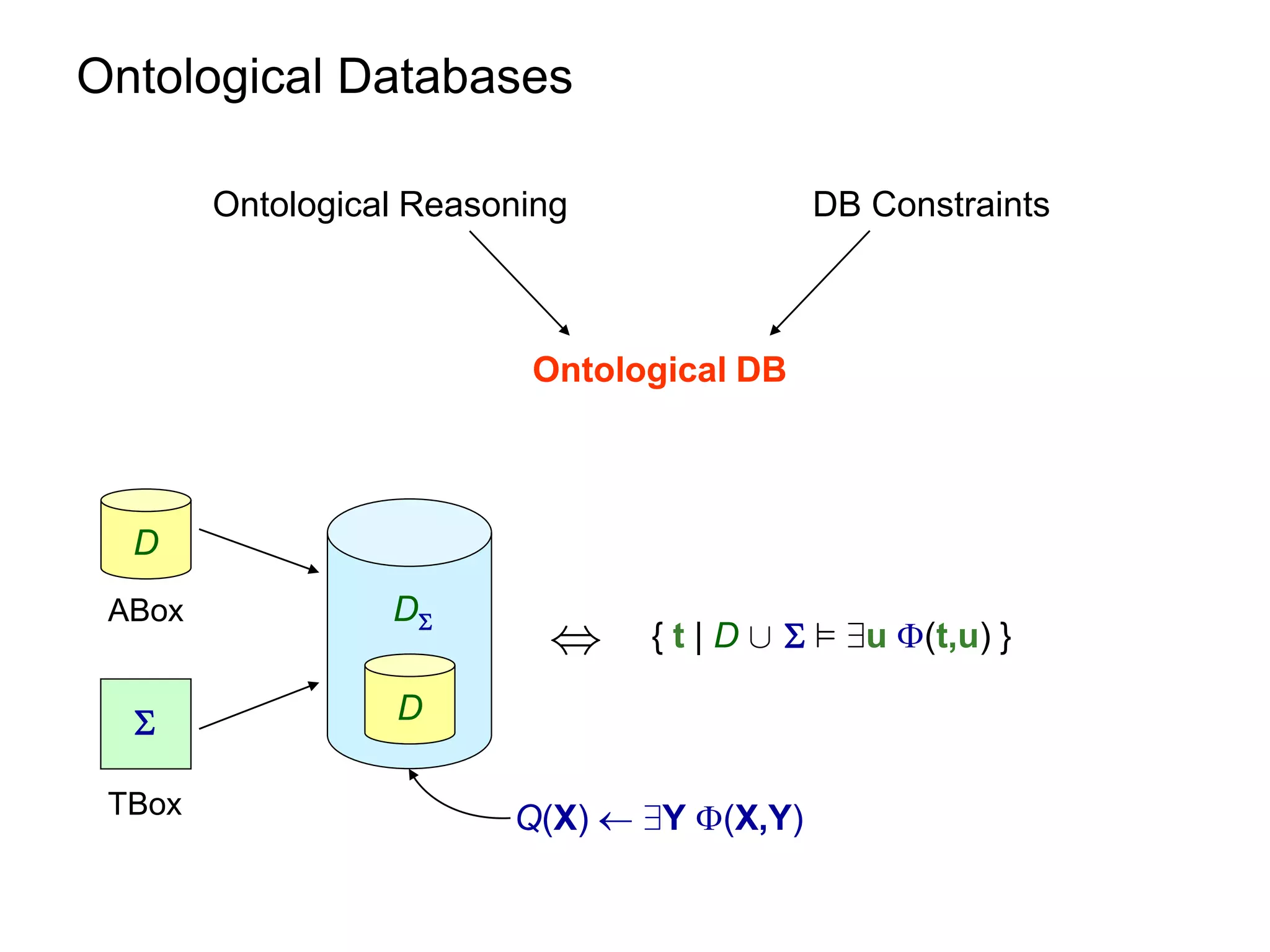

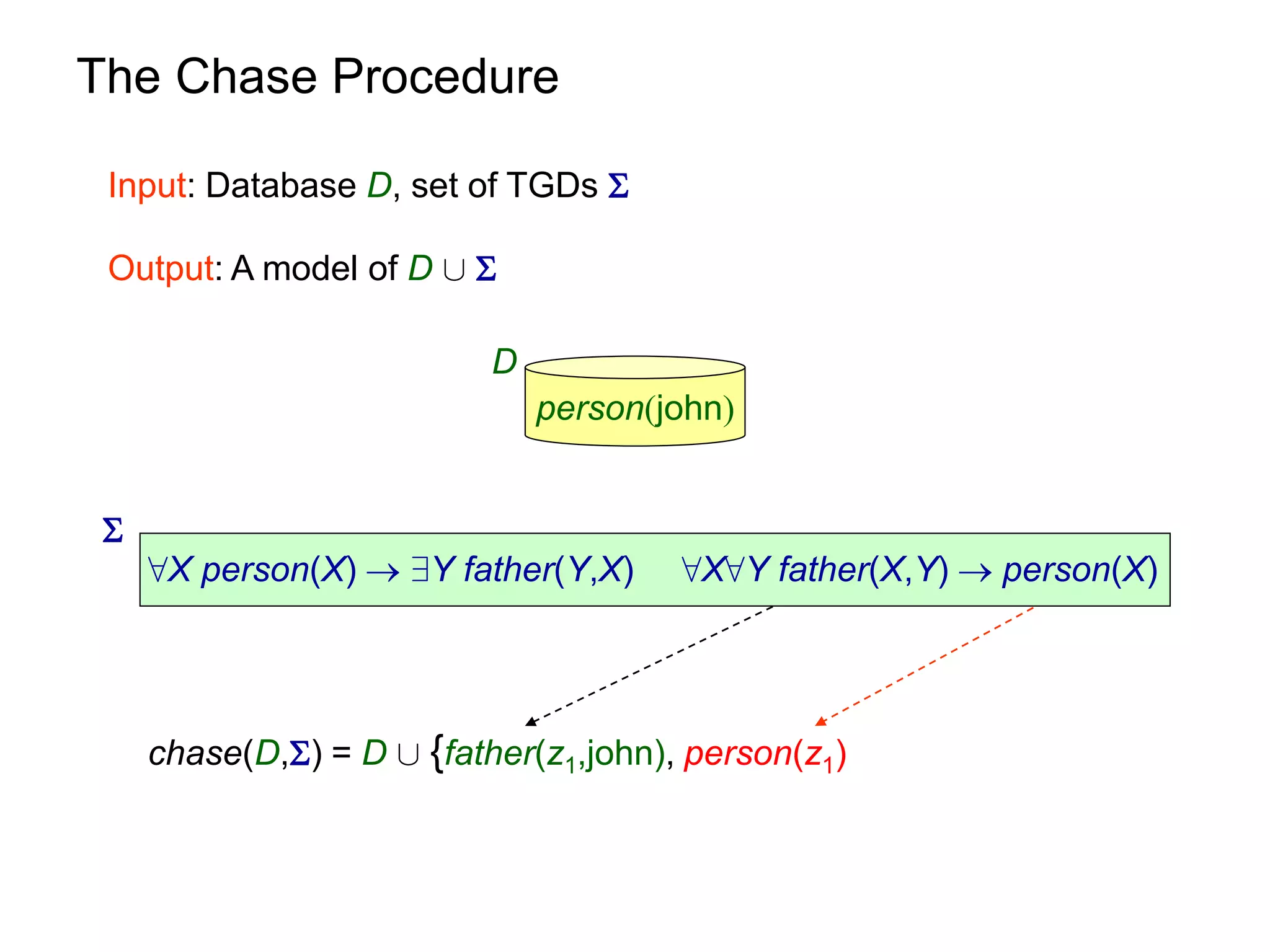

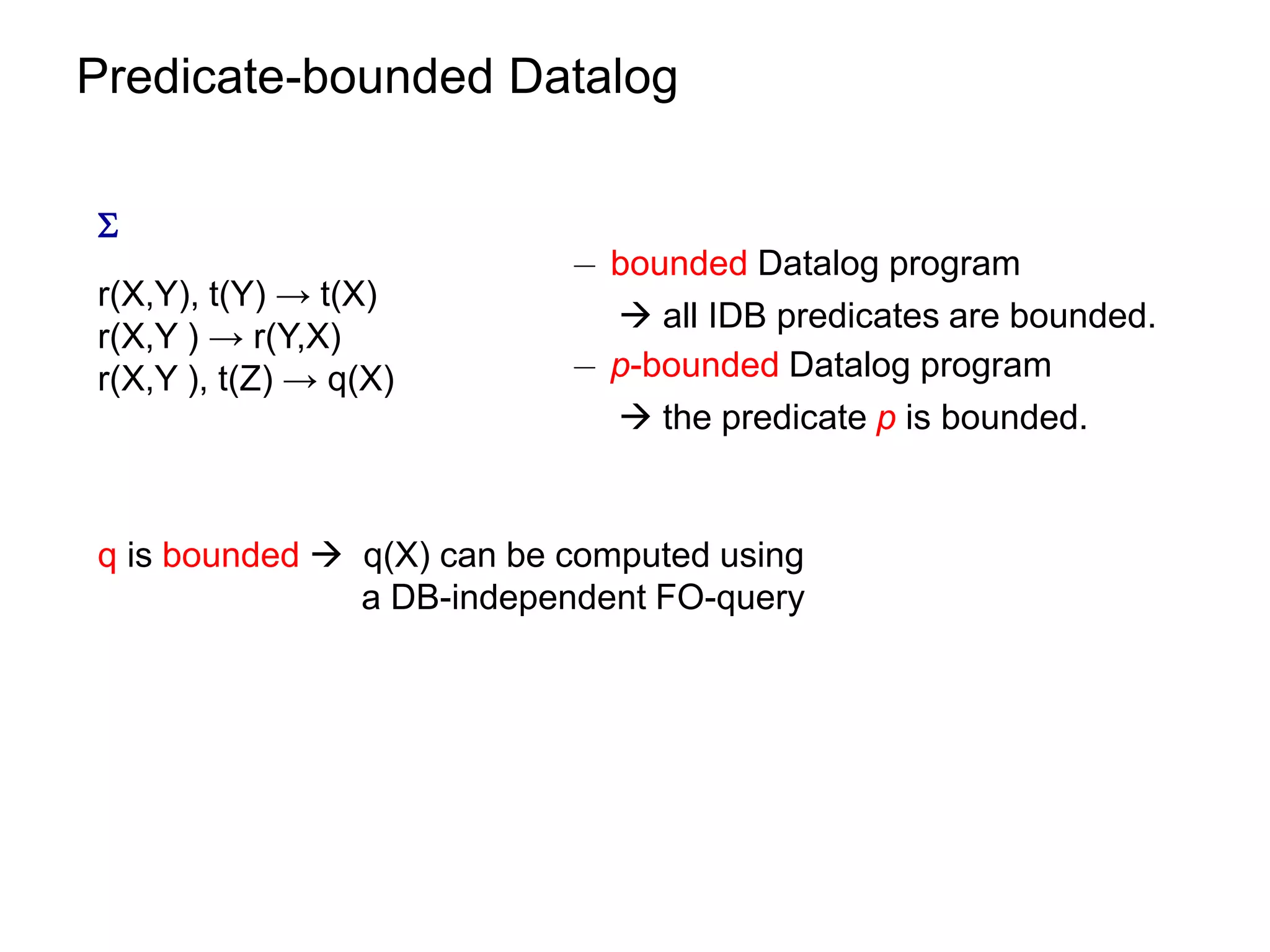

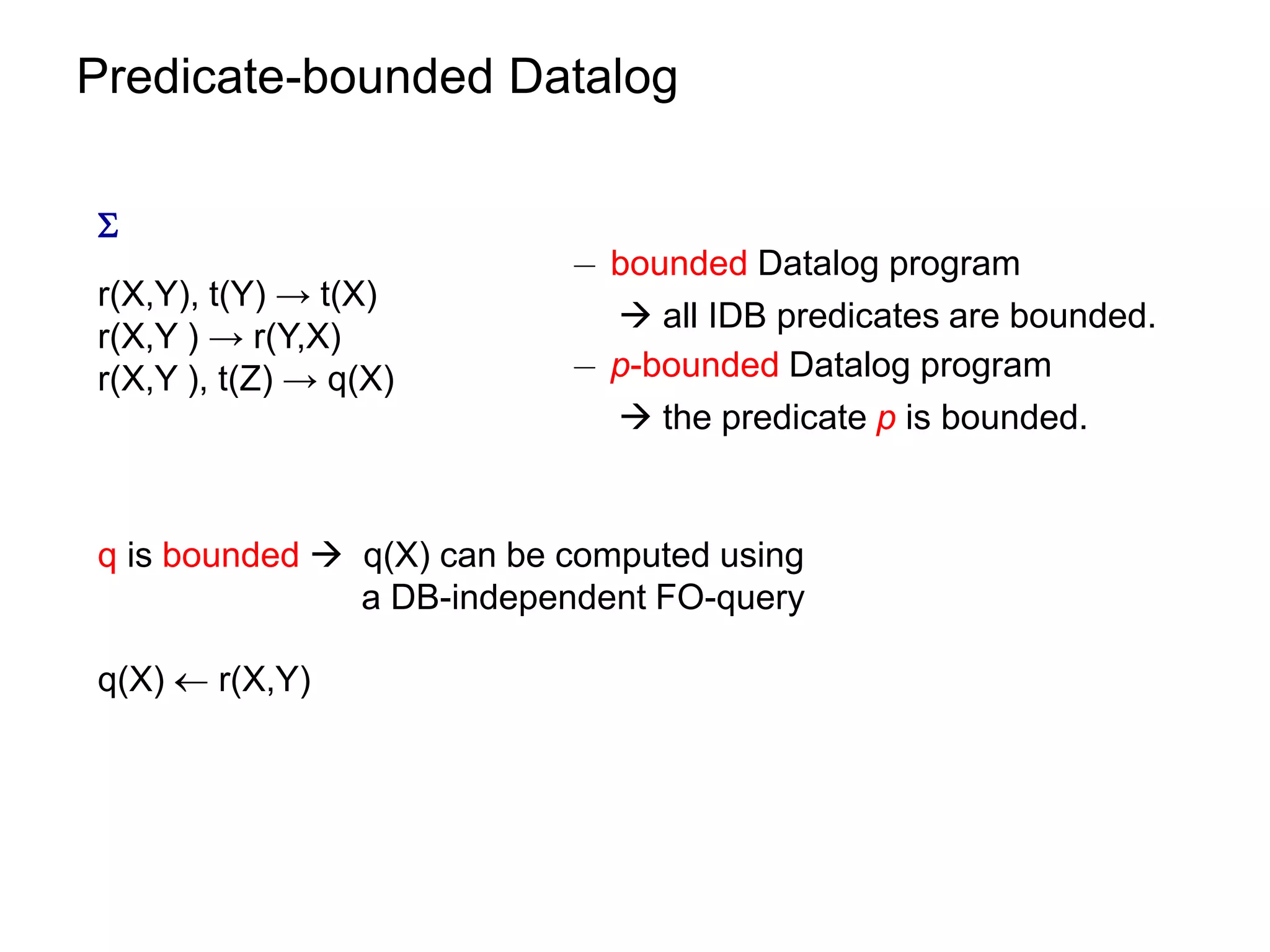

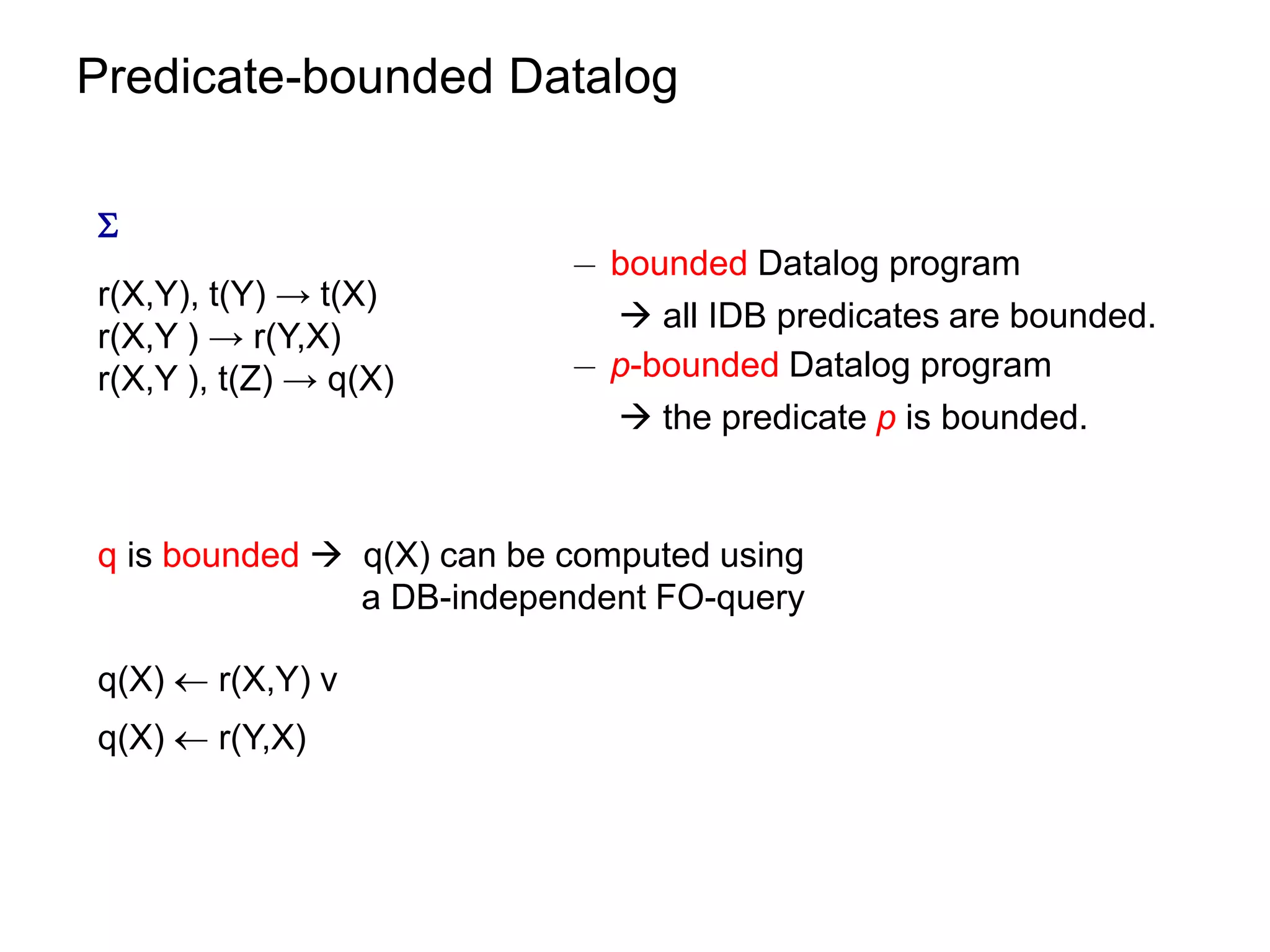

This document summarizes research on optimizing query answering under ontological constraints. Specifically, it discusses:

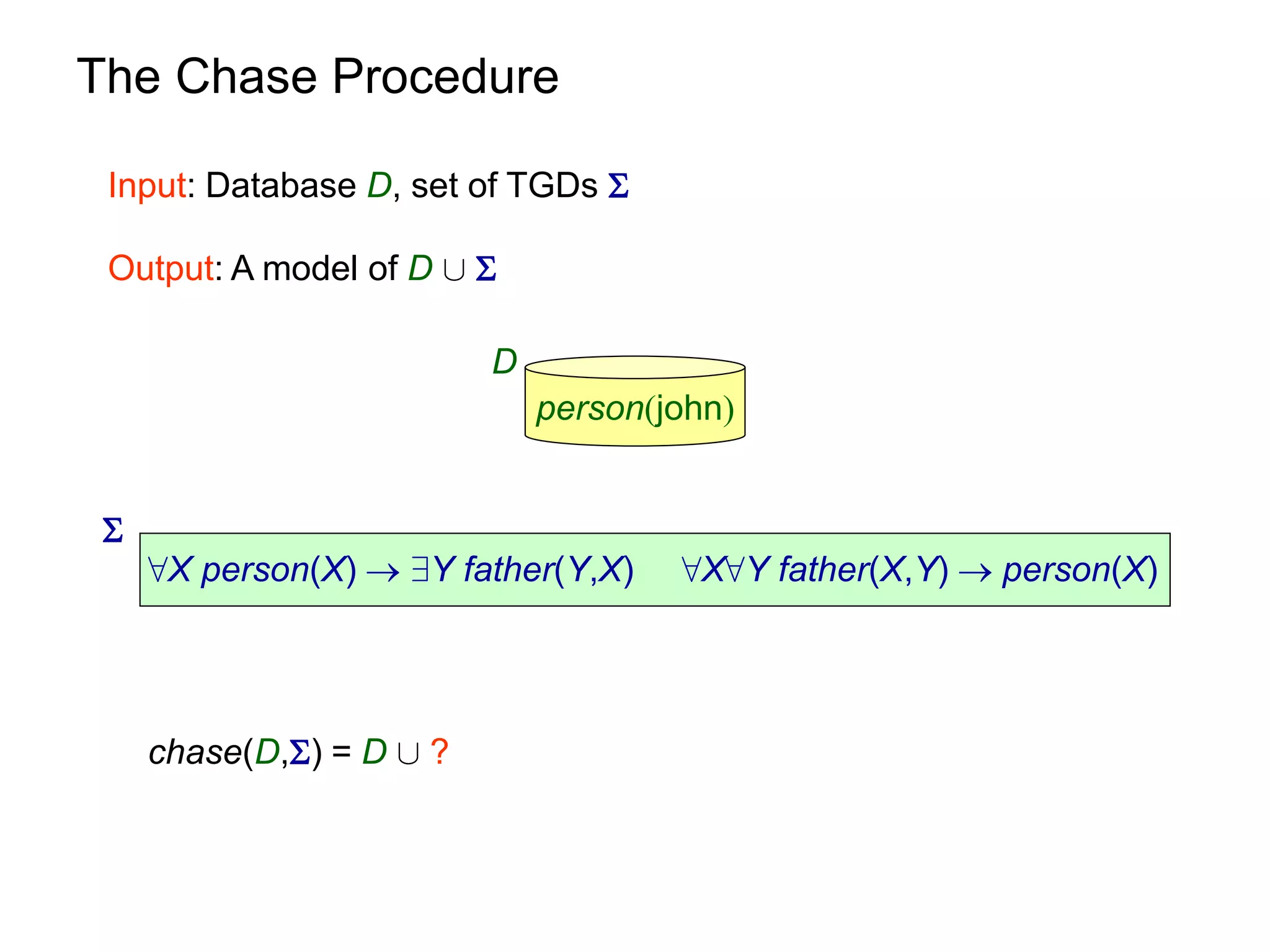

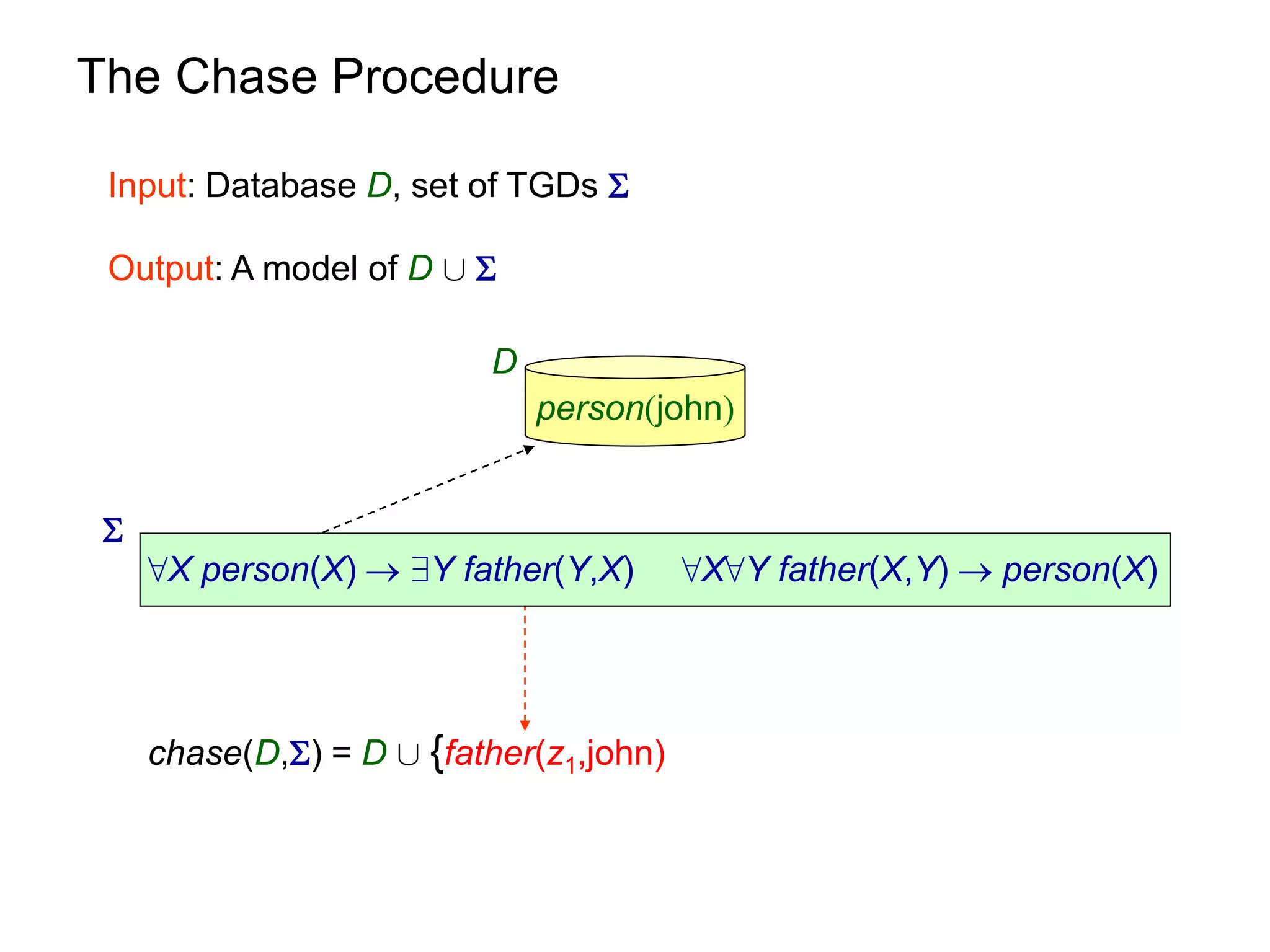

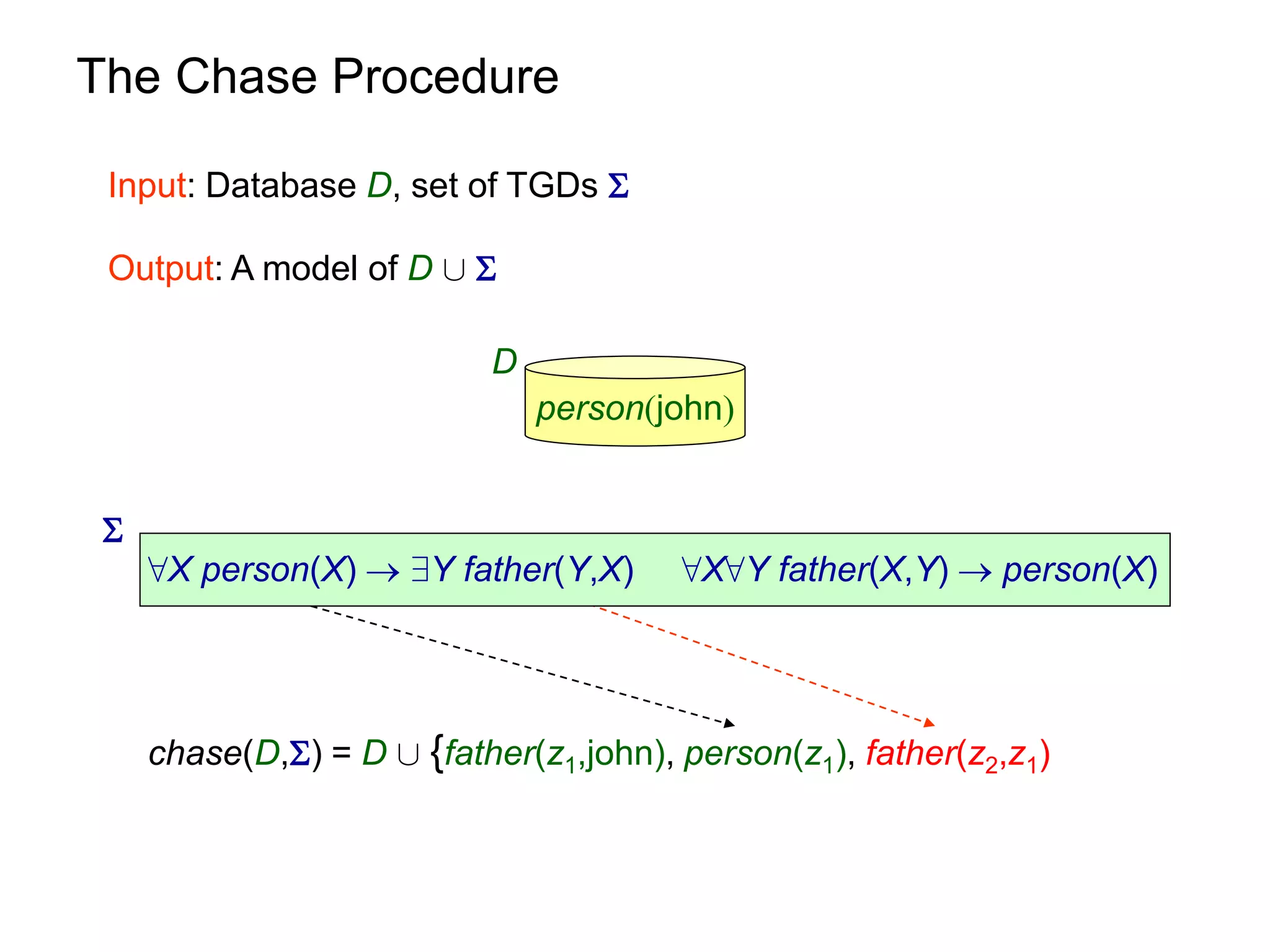

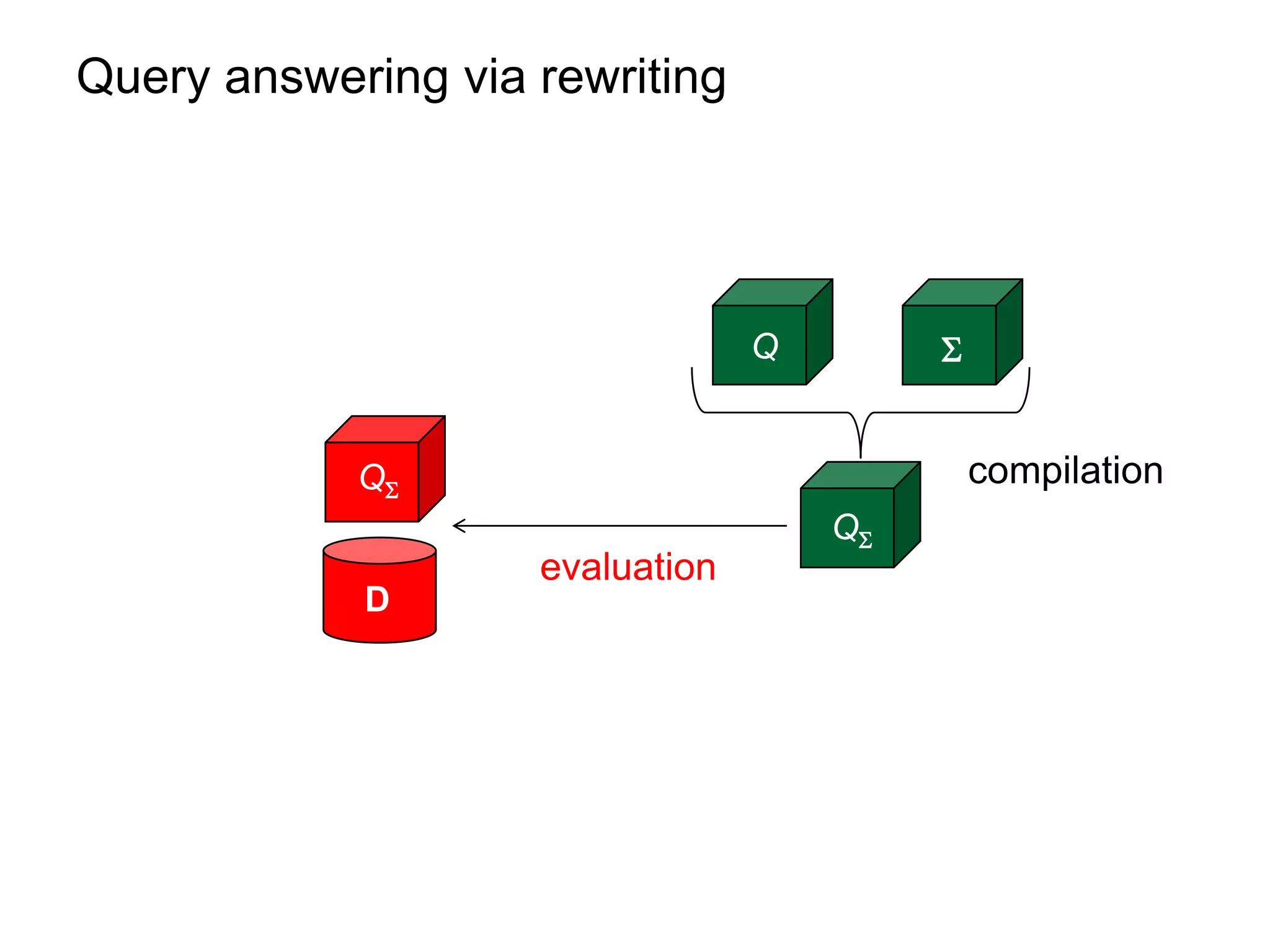

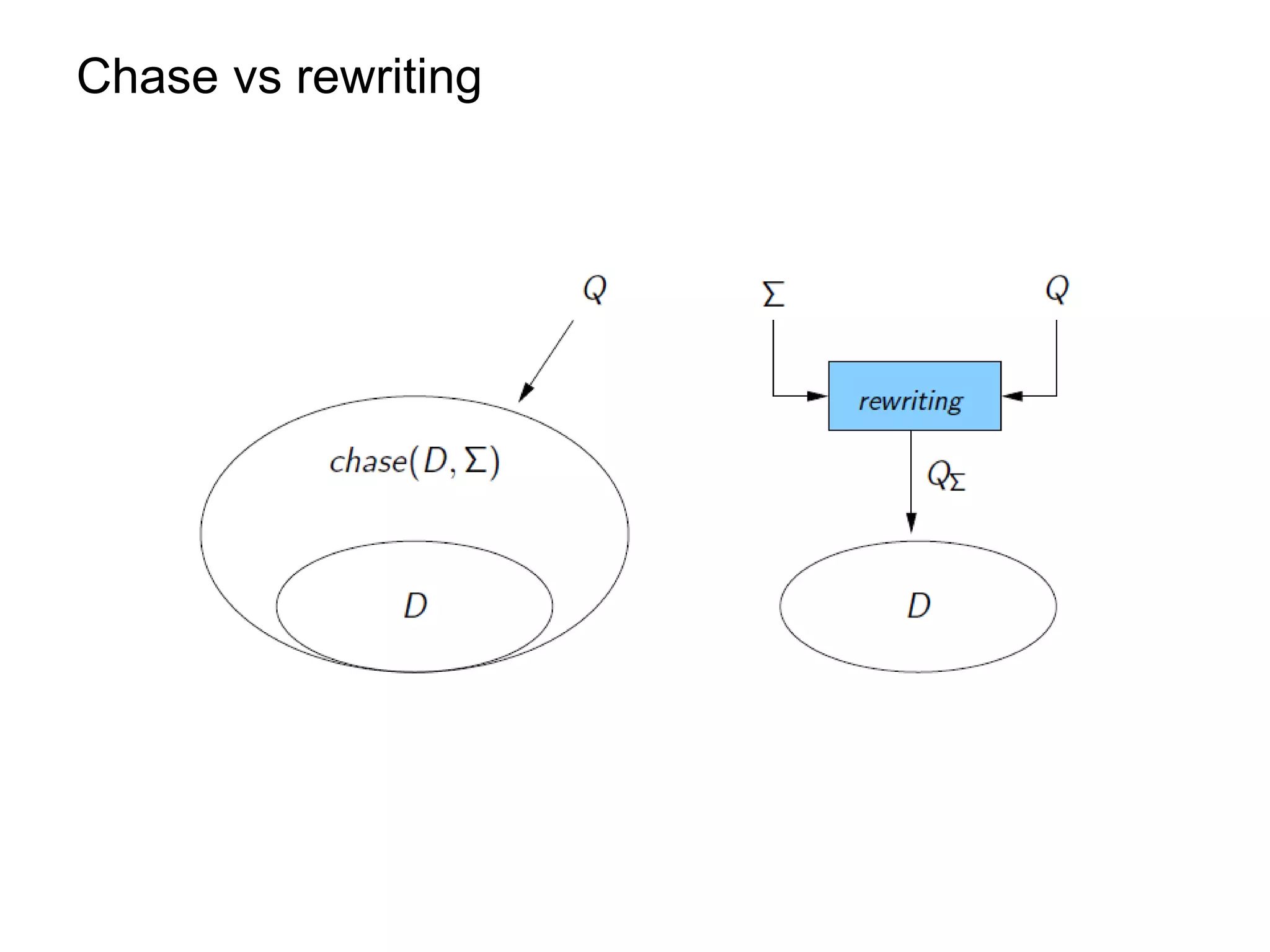

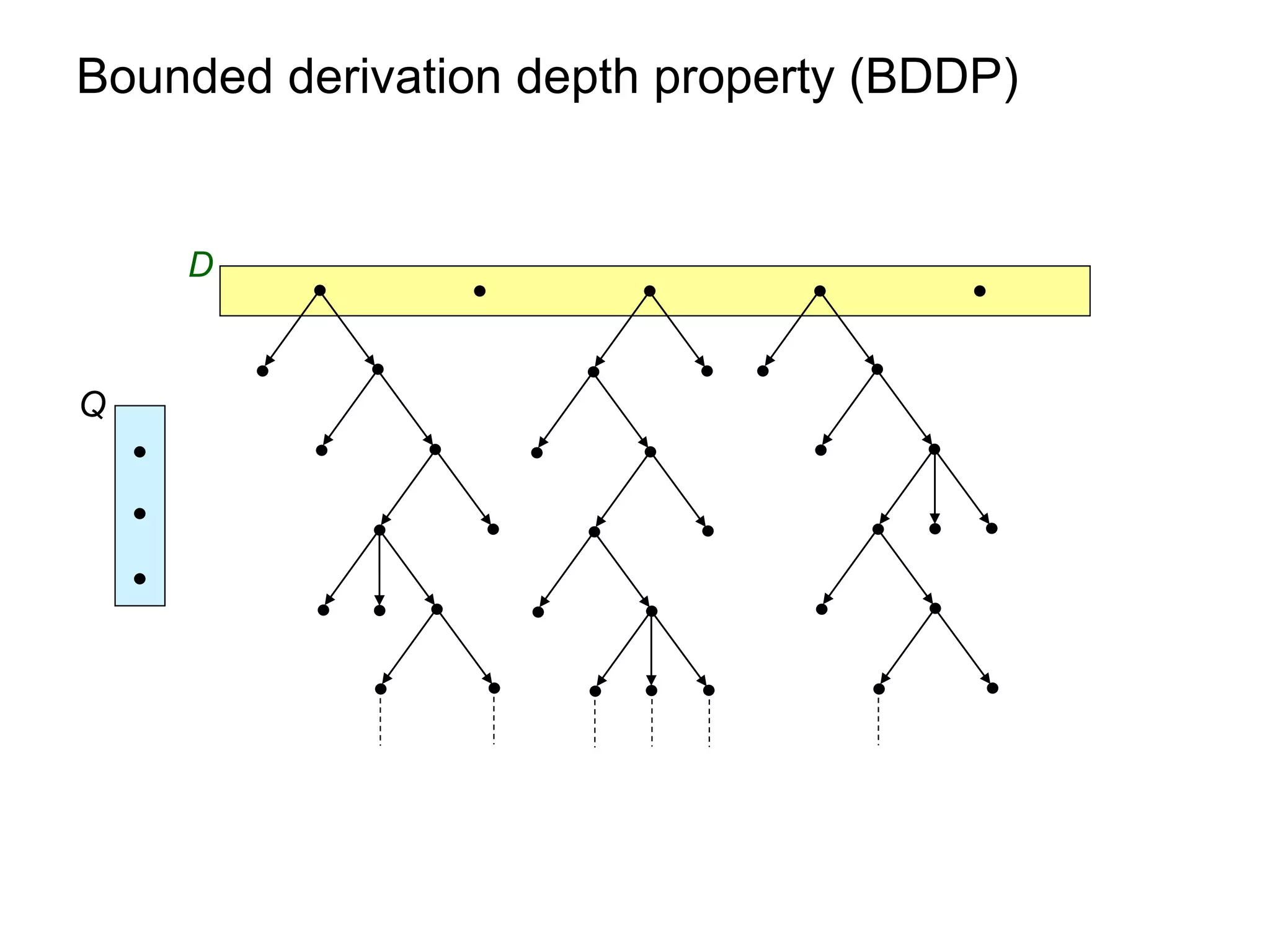

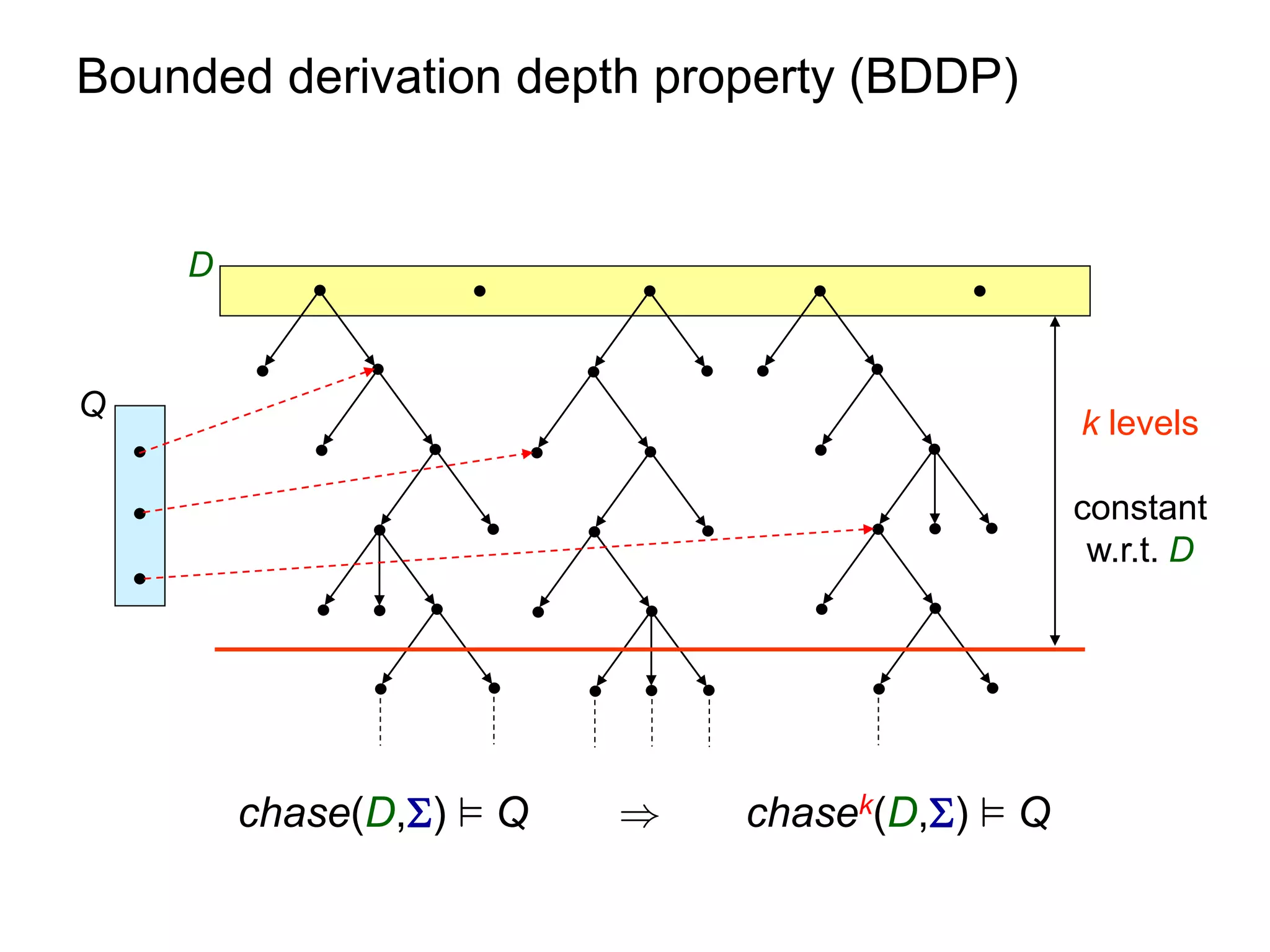

1) Using the chase procedure to compute a model of the database extended with the ontological constraints, and then evaluating queries over this model.

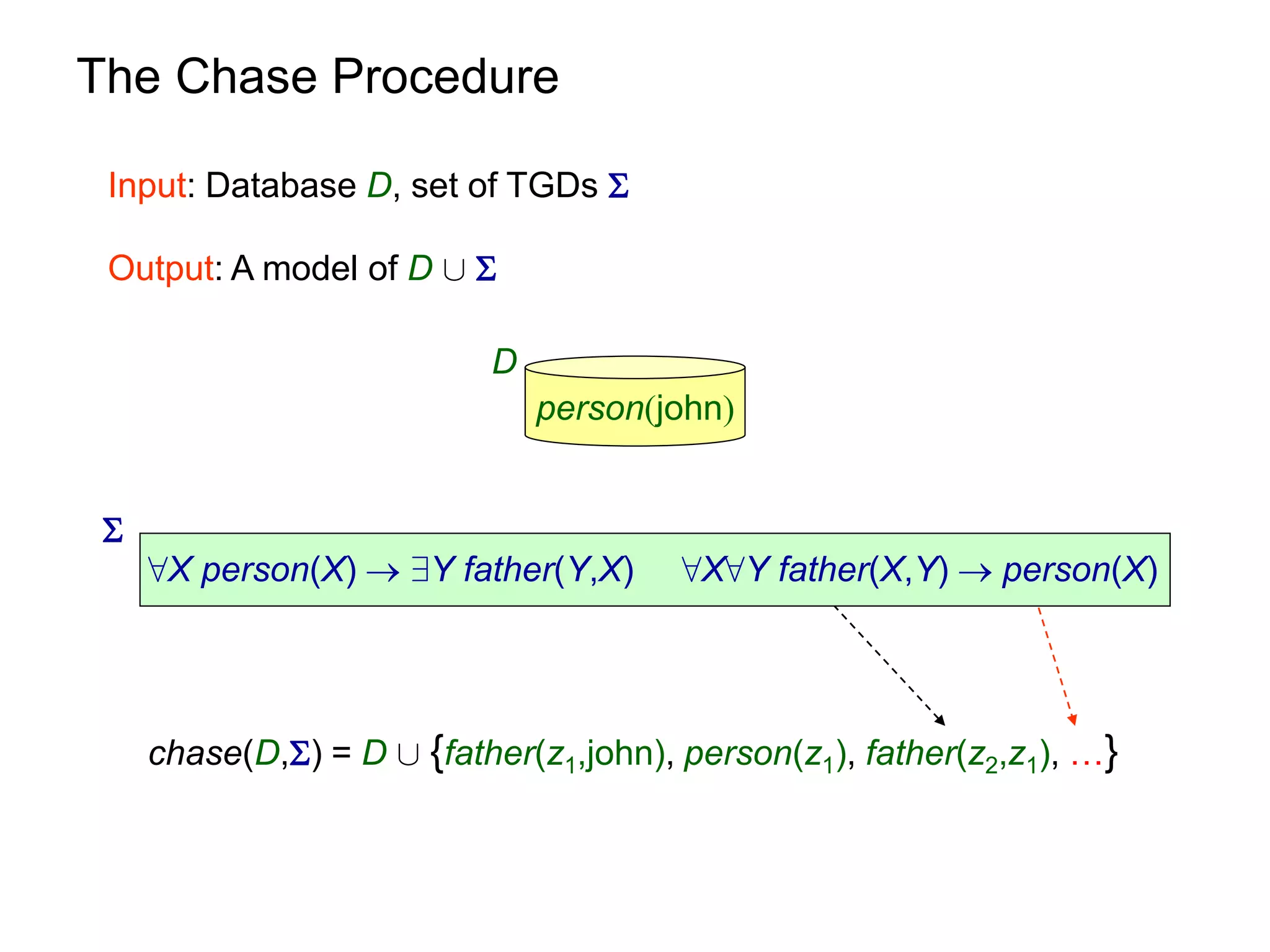

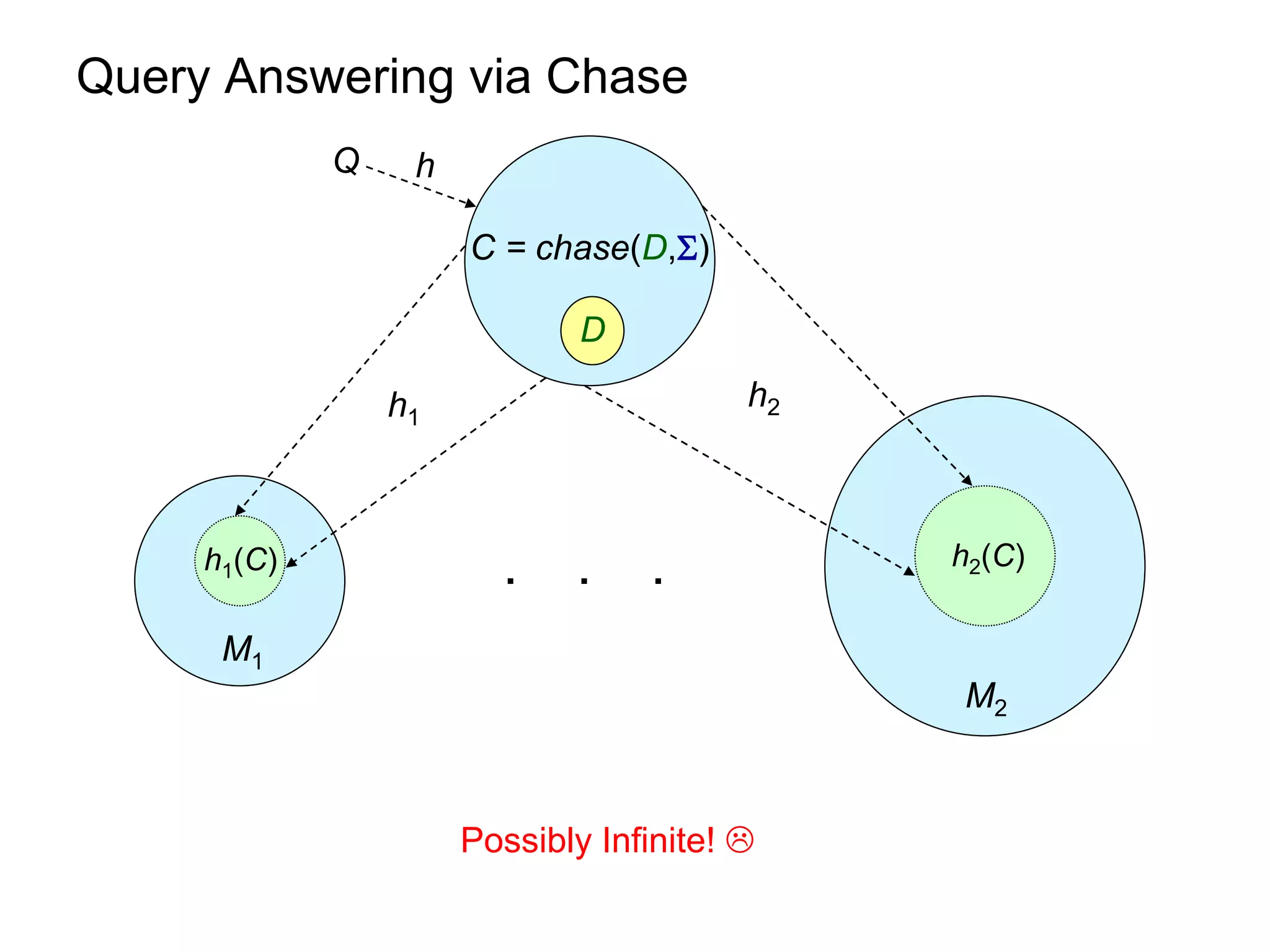

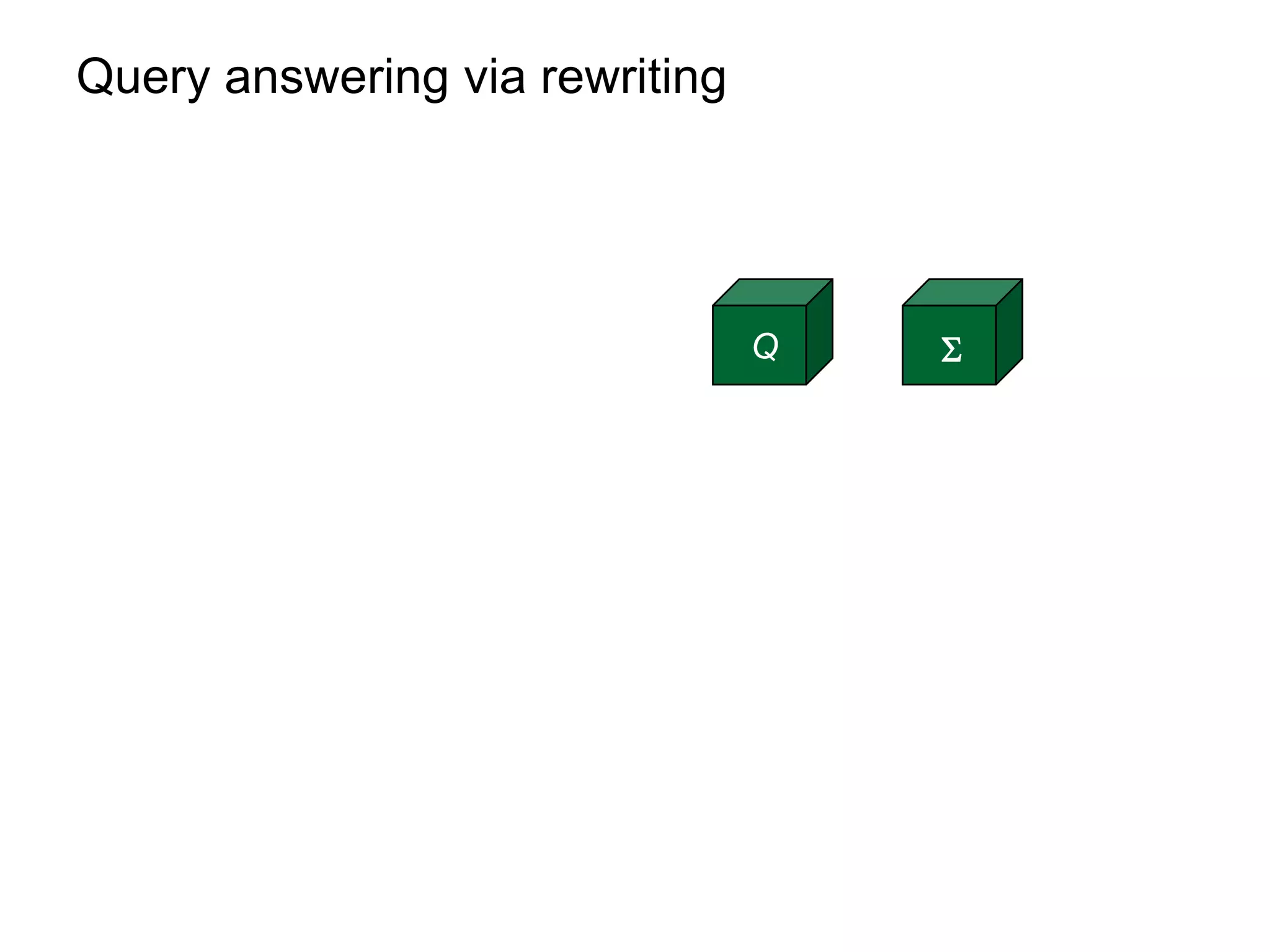

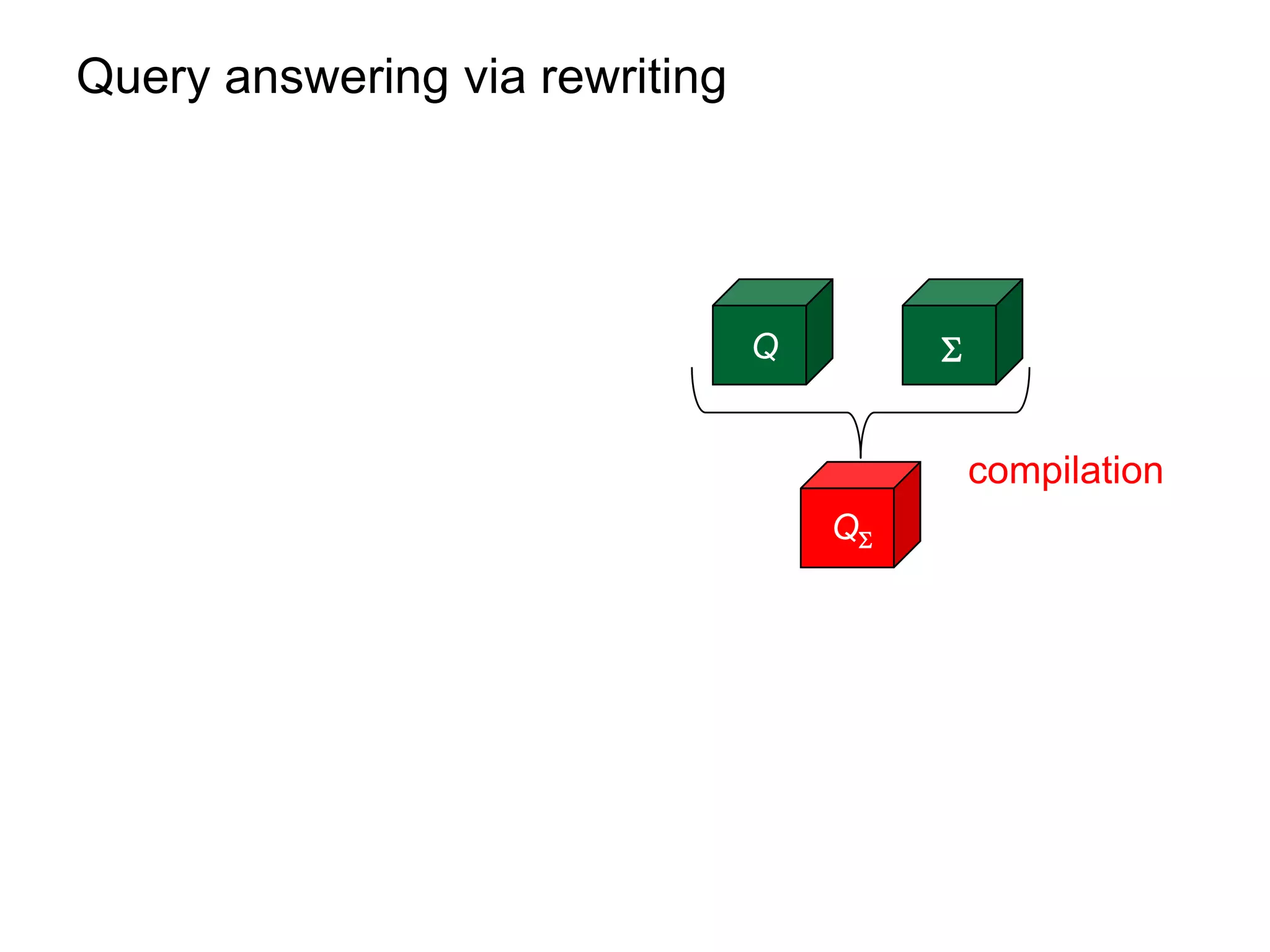

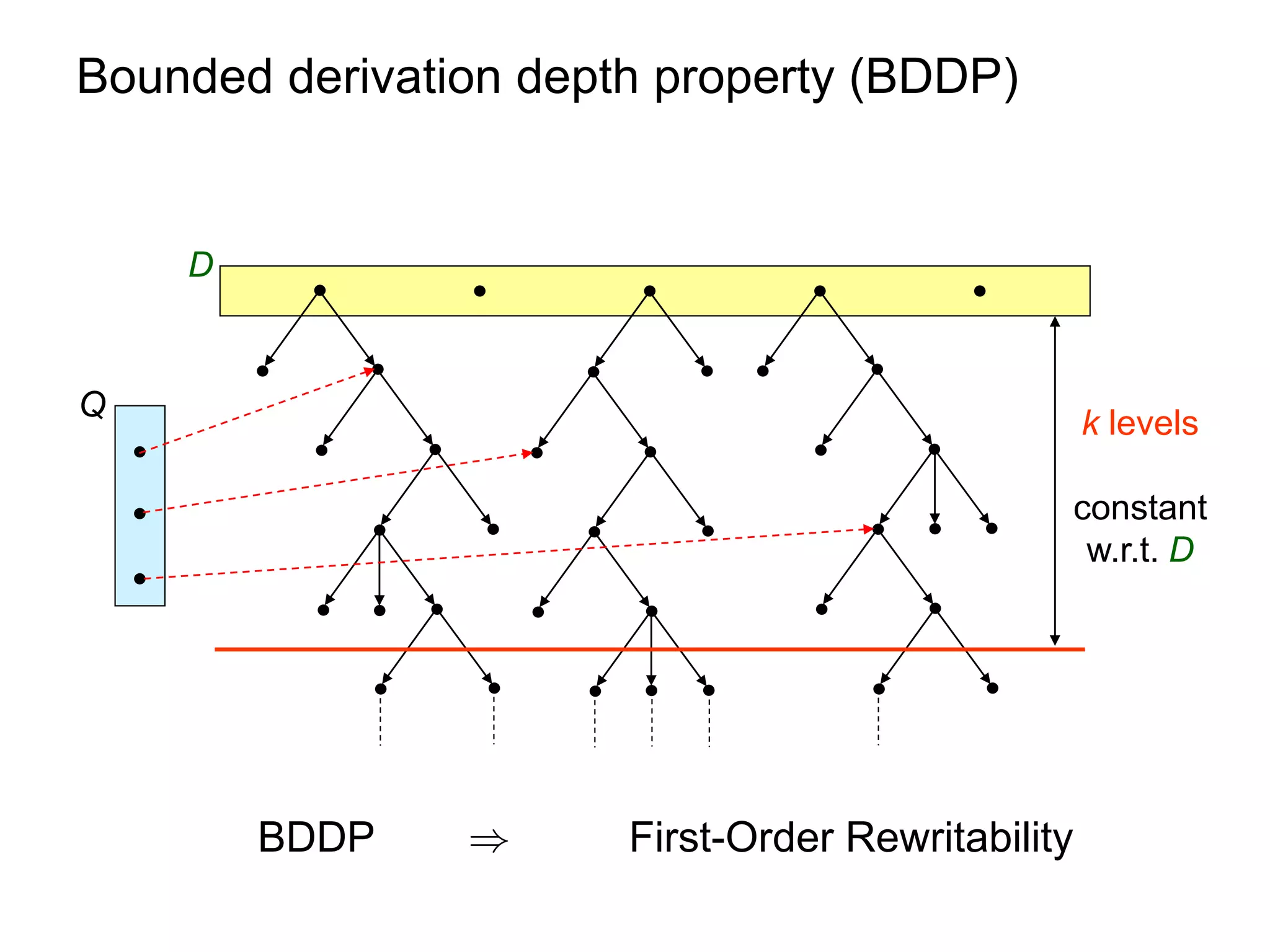

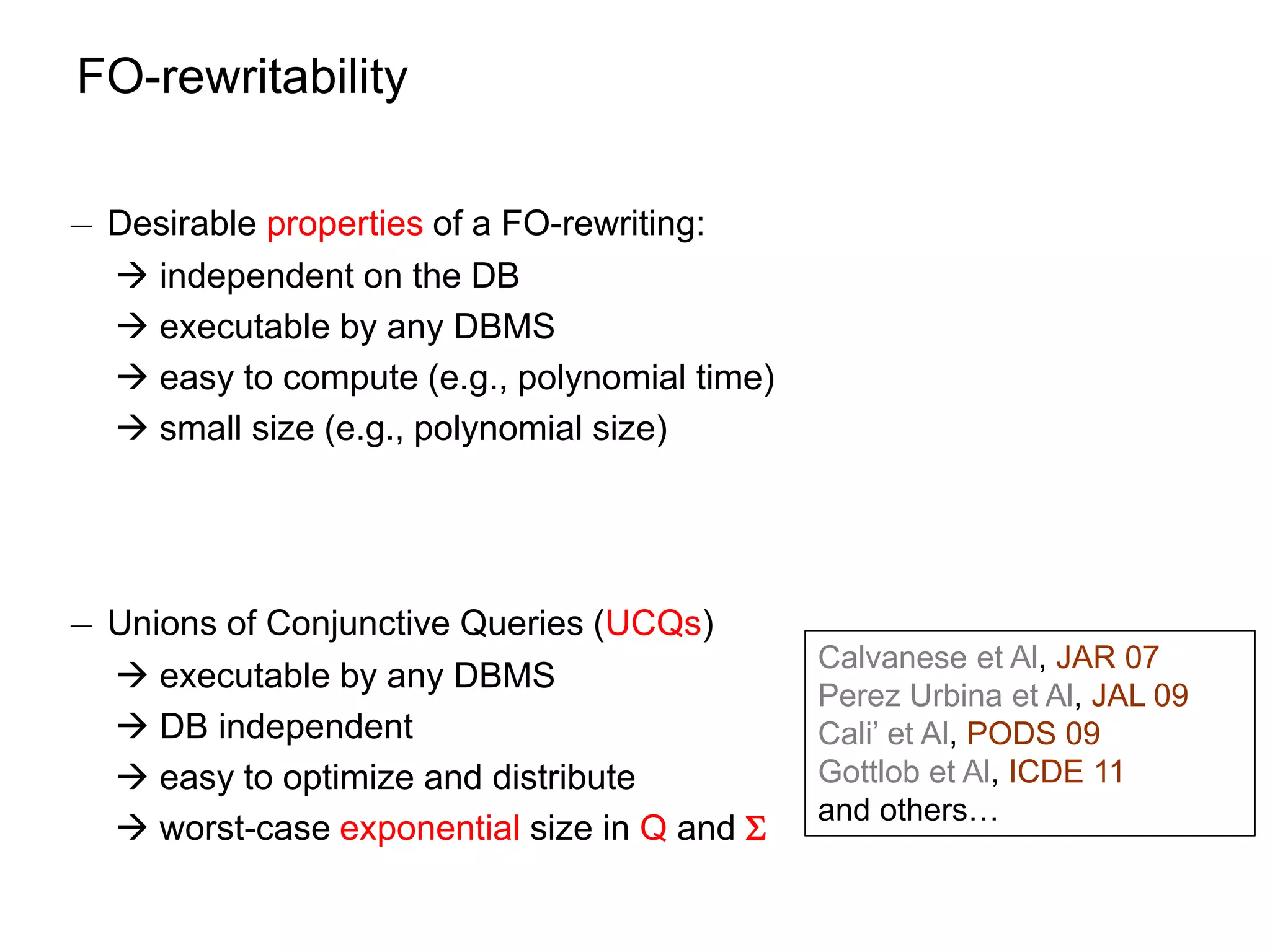

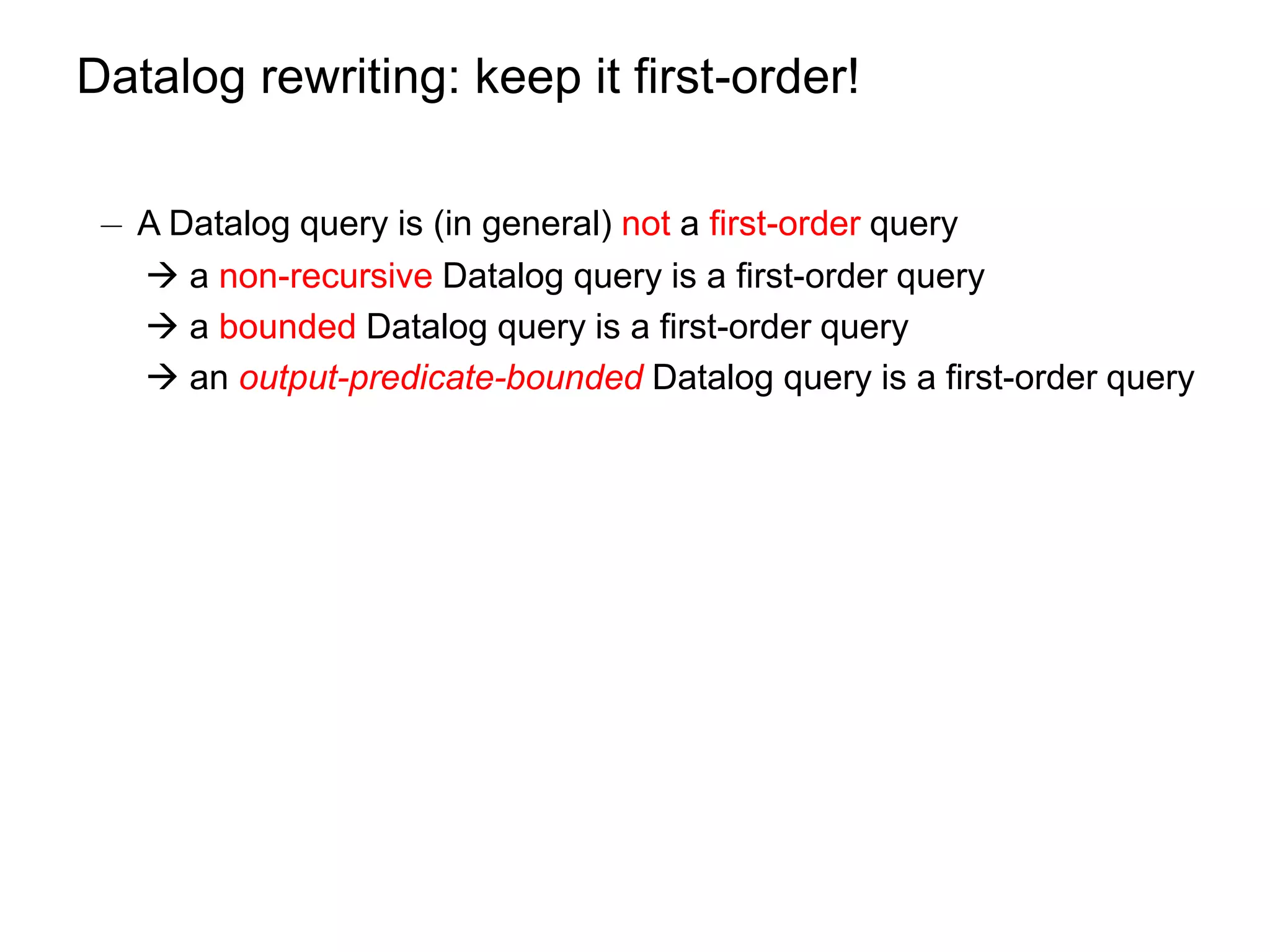

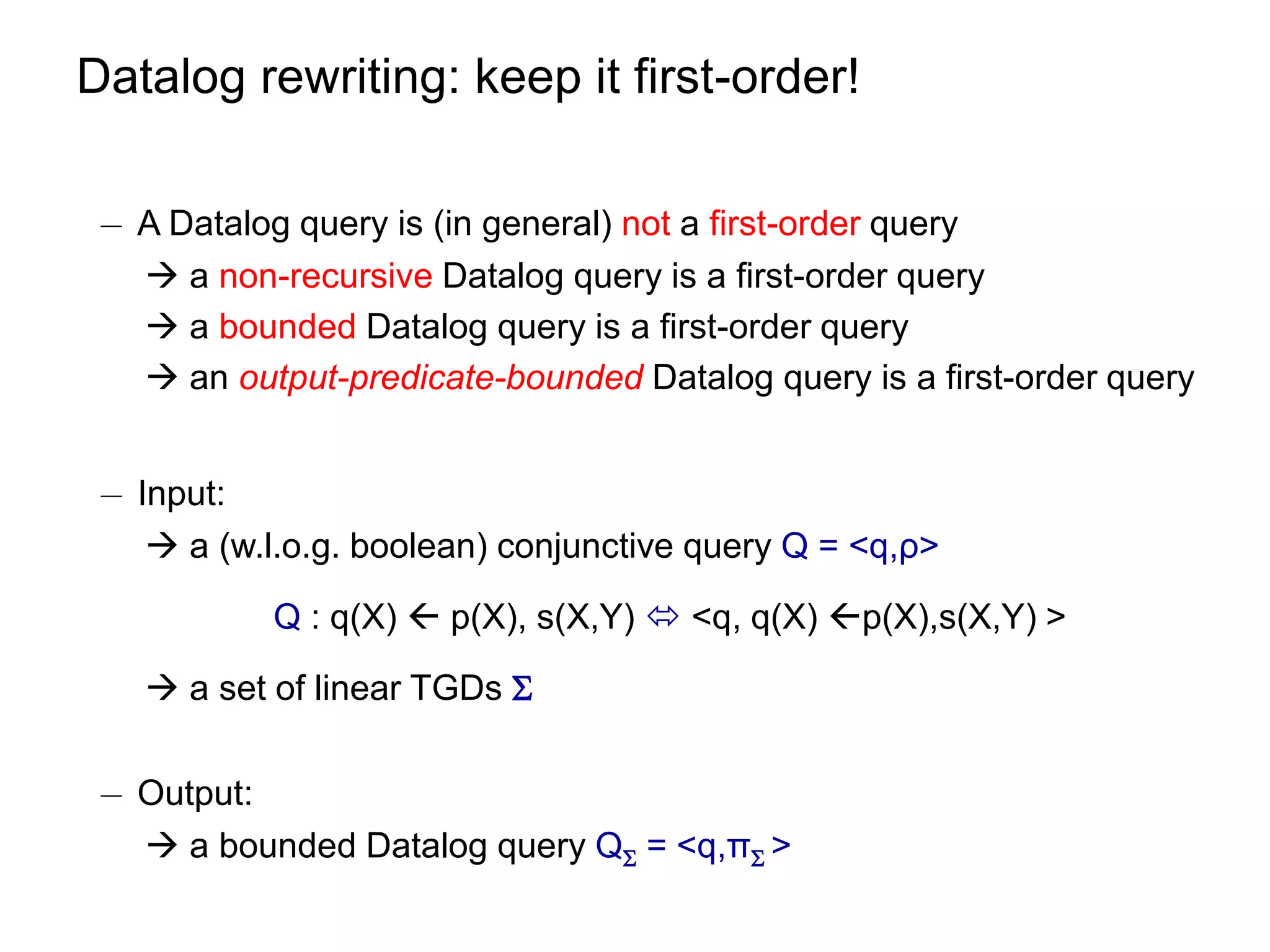

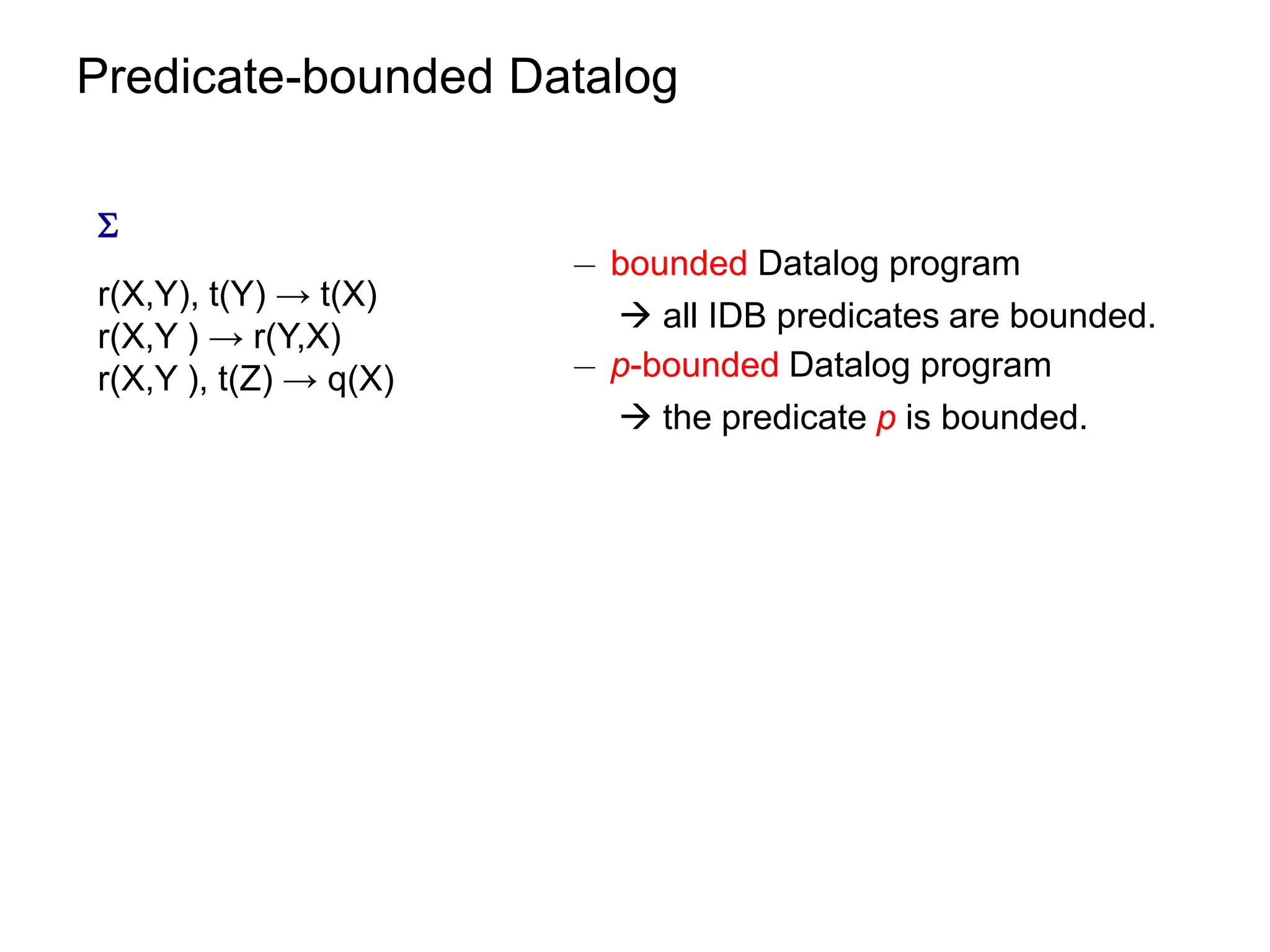

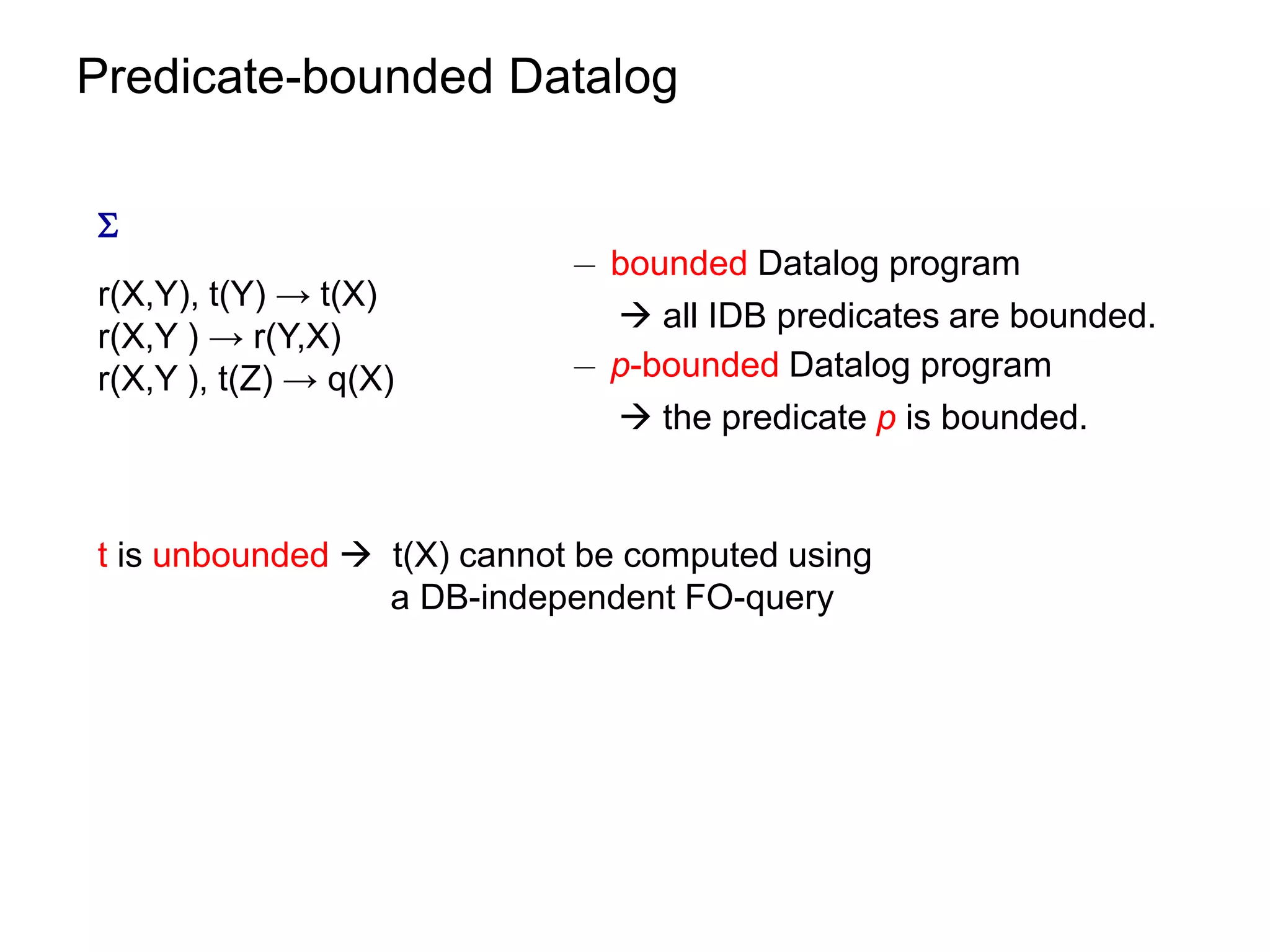

2) Rewriting queries using the ontological constraints into first-order rewritings that can be evaluated directly over the database.

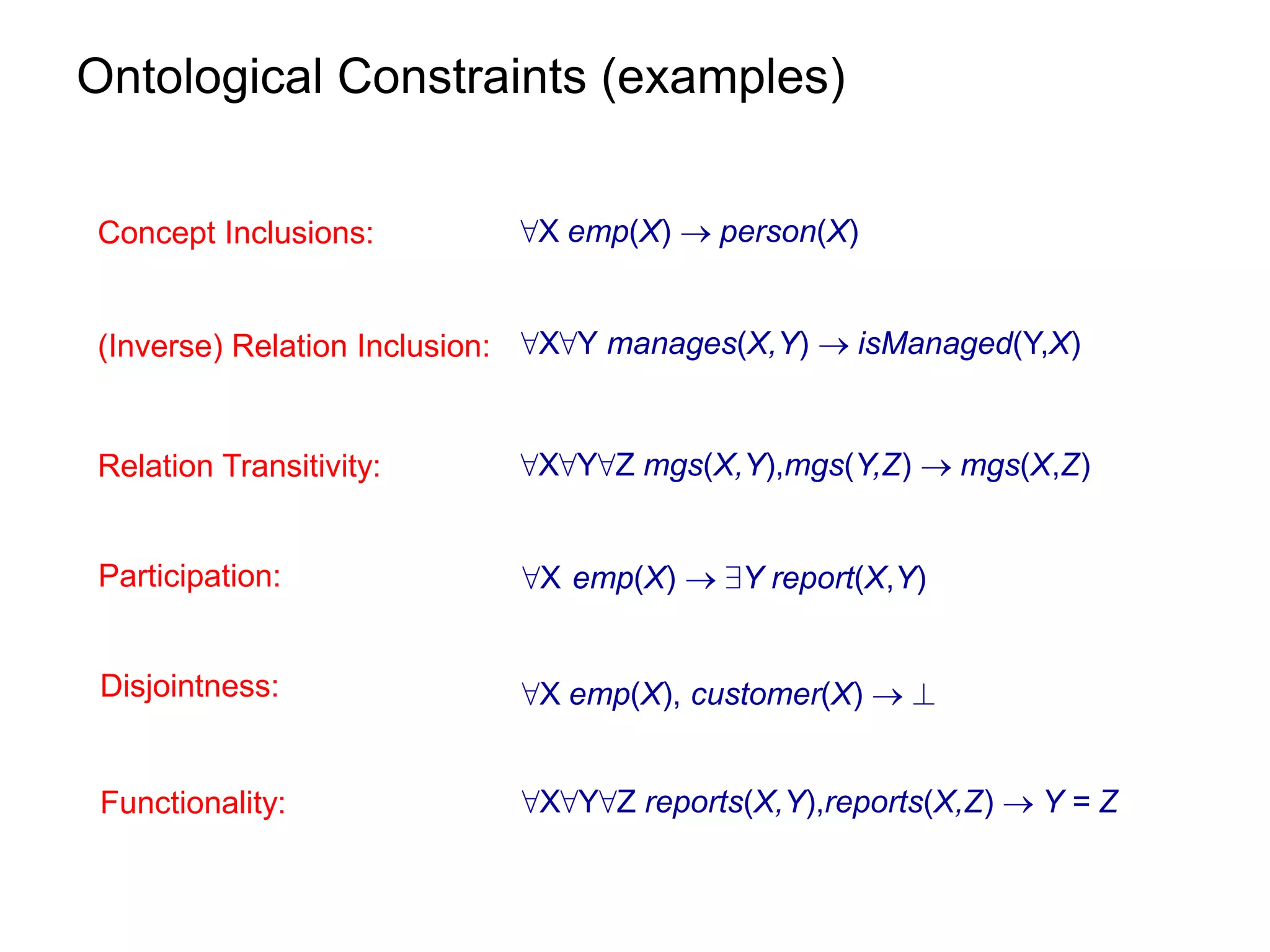

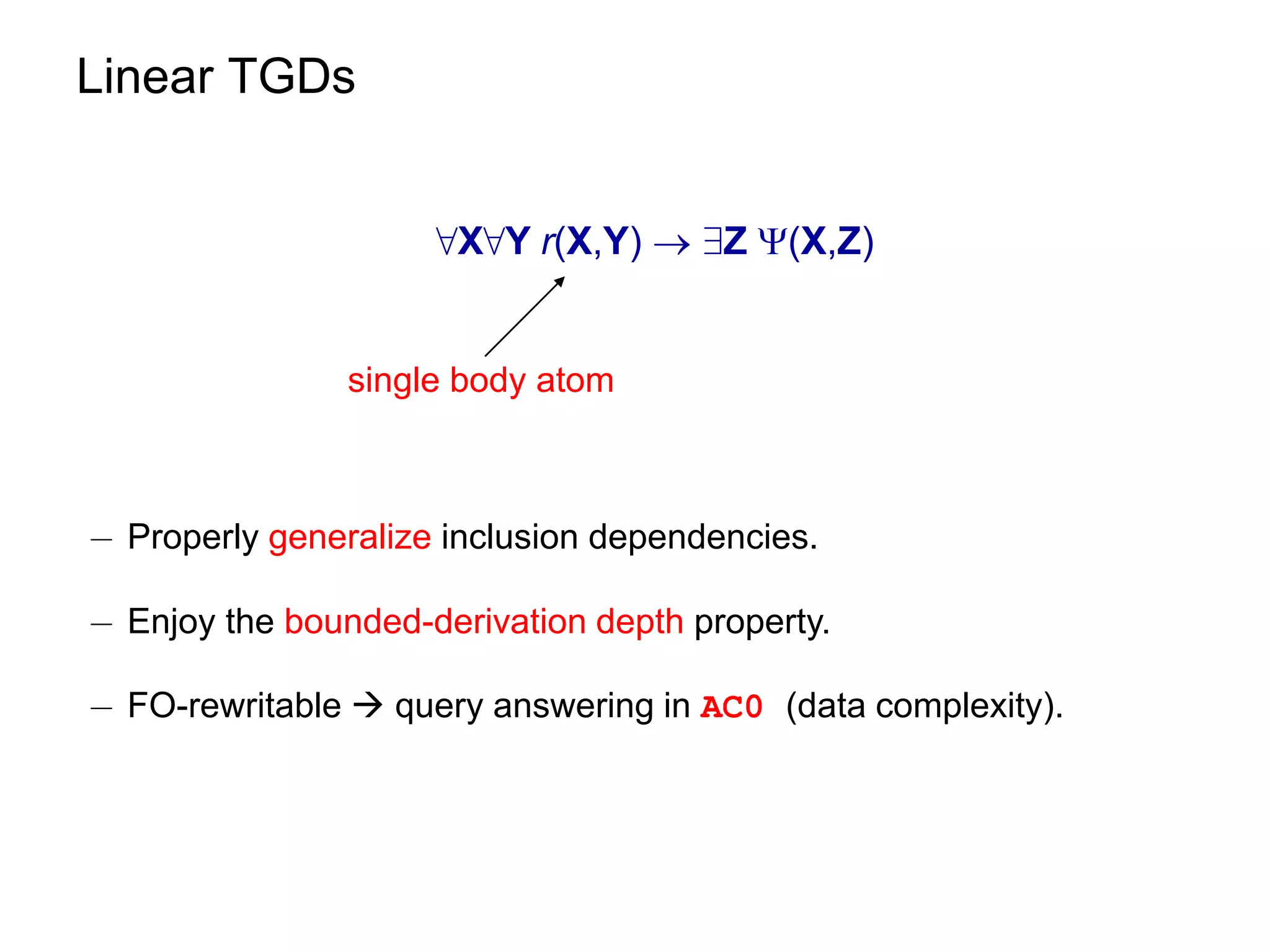

3) Properties of ontological constraints, like linear tuple-generating dependencies, that ensure the chase terminates and queries can be rewritten as first-order queries, allowing for efficient query evaluation.

![Datalog§ [Cali’ et Al, PODS 09]

¡ Datalog variant allowing in the head:

- 9-variables ! TGDs 8X8Y (X,Y) 9Z (X,Z)

- Equality atoms ! EGDs 8X (X) Xi=Xj Datalog+

- Constant false (?) ! NCs 8X (X) ?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-7-2048.jpg)

![Datalog§ [Cali’ et Al, PODS 09]

¡ Datalog variant allowing in the head:

- 9-variables ! TGDs 8X8Y (X,Y) 9Z (X,Z)

- Equality atoms ! EGDs 8X (X) Xi=Xj Datalog+

- Constant false (?) ! NCs 8X (X) ?

¡ But, query answering under Datalog+ is undecidable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-8-2048.jpg)

![Datalog§ [Cali’ et Al, PODS 09]

¡ Datalog variant allowing in the head:

- 9-variables ! TGDs 8X8Y (X,Y) 9Z (X,Z)

- Equality atoms ! EGDs 8X (X) Xi=Xj Datalog+

- Constant false (?) ! NCs 8X (X) ?

¡ But, query answering under Datalog+ is undecidable

¡ Datalog+ is syntactically restricted ! Datalog§](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-9-2048.jpg)

![Datalog§ [Cali’ et Al, PODS 09]

¡ Datalog variant allowing in the head:

- 9-variables ! TGDs 8X8Y (X,Y) 9Z (X,Z)

- Equality atoms ! EGDs 8X (X) Xi=Xj Datalog+

- Constant false (?) ! NCs 8X (X) ?

¡ But, query answering under Datalog+ is undecidable

¡ Datalog+ is syntactically restricted ! Datalog§

¡ TGDs more expressive than inclusion dependencies

8D8P8A runs(D,P),area(P,A) 9E employee(E,D,A)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-10-2048.jpg)

![Query Answering via Chase

Q h

C = chase(D,)

D

h1 h2

h2(C)

h1(C) . . .

M1

M2

D[²Q , chase(D,) ² Q

[see, e.g., Deutsch, Nash & Remmel, PODS 08]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-16-2048.jpg)

![FO-rewritability: Example [Gottlob et Al., ICDE 11]

promoter(X) Y promotesTo(X,Y)

promotesTo(X,Y) customer(Y)

Q q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

Q

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B) (original query)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-26-2048.jpg)

![FO-rewritability: Example [Gottlob et Al., ICDE 11]

promoter(X) Y promotesTo(X,Y)

promotesTo(X,Y) customer(Y)

Q q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

Q

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B) {Y=B}

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(V0,B) ( V0 is fresh )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-27-2048.jpg)

![FO-rewritability: Example [Gottlob et Al., ICDE 11]

promoter(X) Y promotesTo(X,Y)

promotesTo(X,Y) customer(Y)

Q q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

Q

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

factorization

q promotesTo(A,B), promotesTo(V0,B) ans(A) promotesTo(A,B)

{ A = V0 }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-28-2048.jpg)

![FO-rewritability: Example [Gottlob et Al., ICDE 11]

promoter(X) Y promotesTo(X,Y)

promotesTo(X,Y) customer(Y)

Q q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

Q

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

q promotesTo(A,B) {X = A, Y = B}

q promoter(A)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-29-2048.jpg)

![FO-rewritability: Example [Gottlob et Al., ICDE 11]

promoter(X) Y promotesTo(X,Y)

promotesTo(X,Y) customer(Y)

Q q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

Q

q promotesTo(A,B), customer(B)

q promotesTo(A,B) UCQ rewriting

(first-order)

q promoter(A)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-30-2048.jpg)

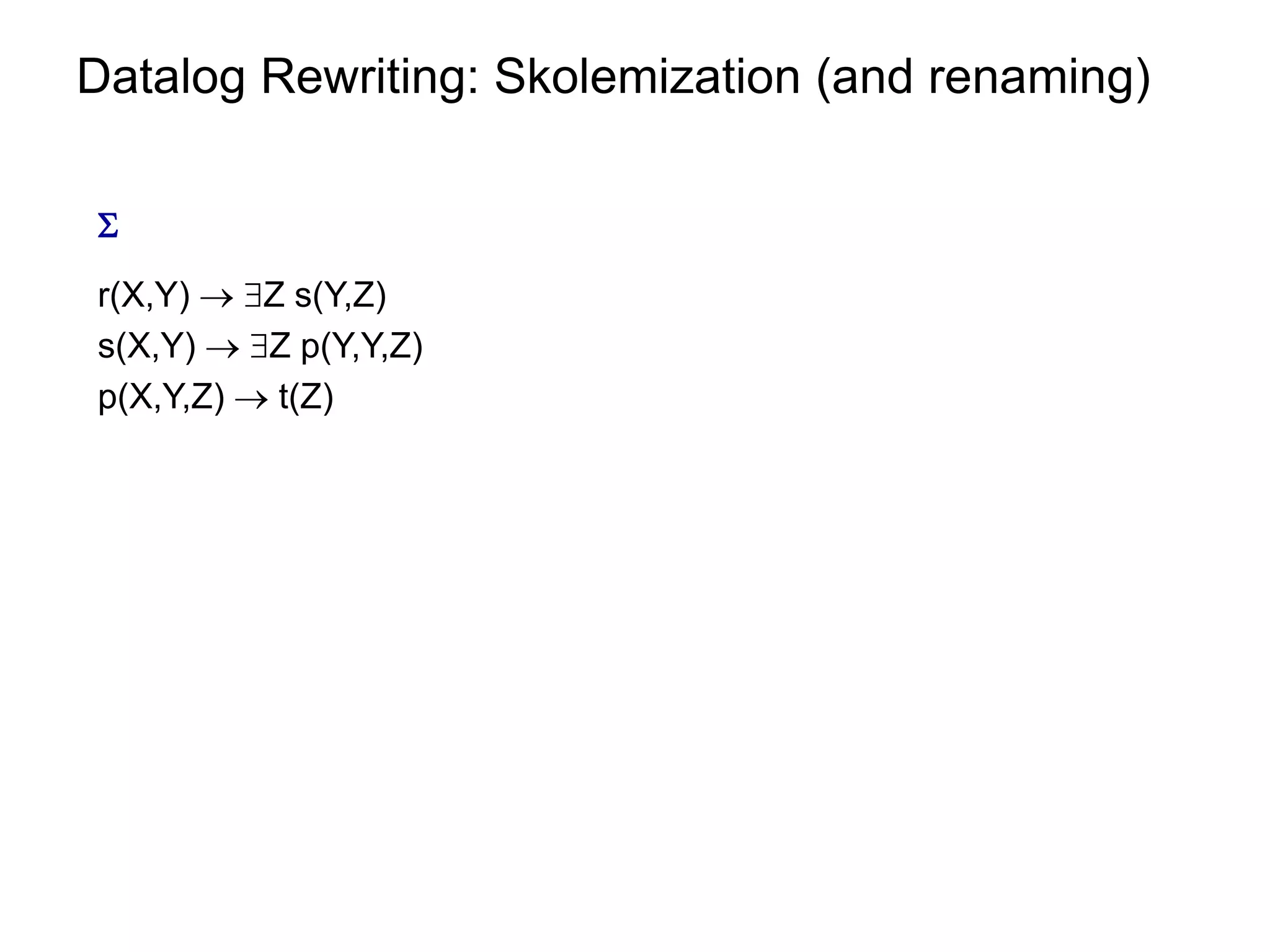

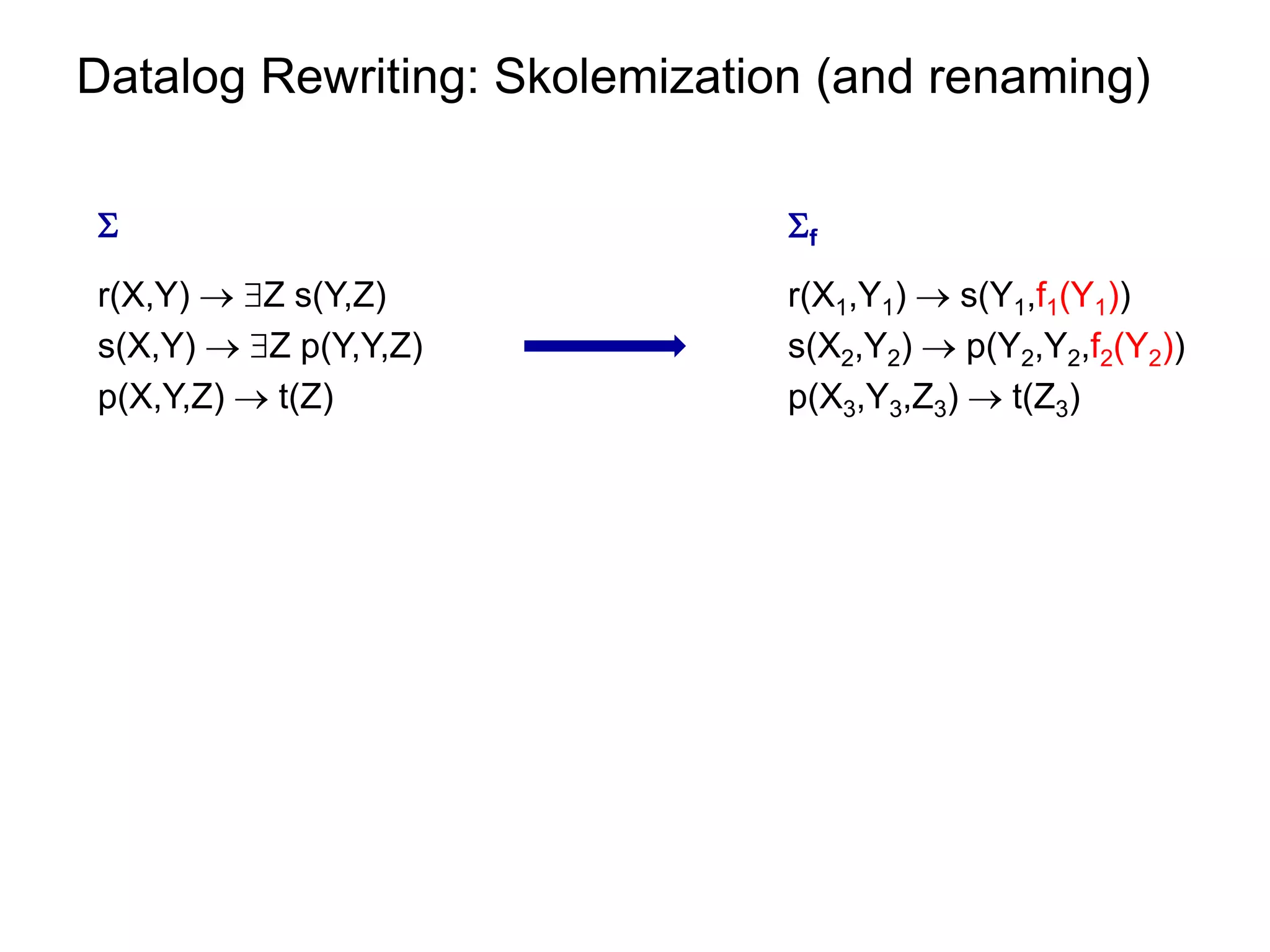

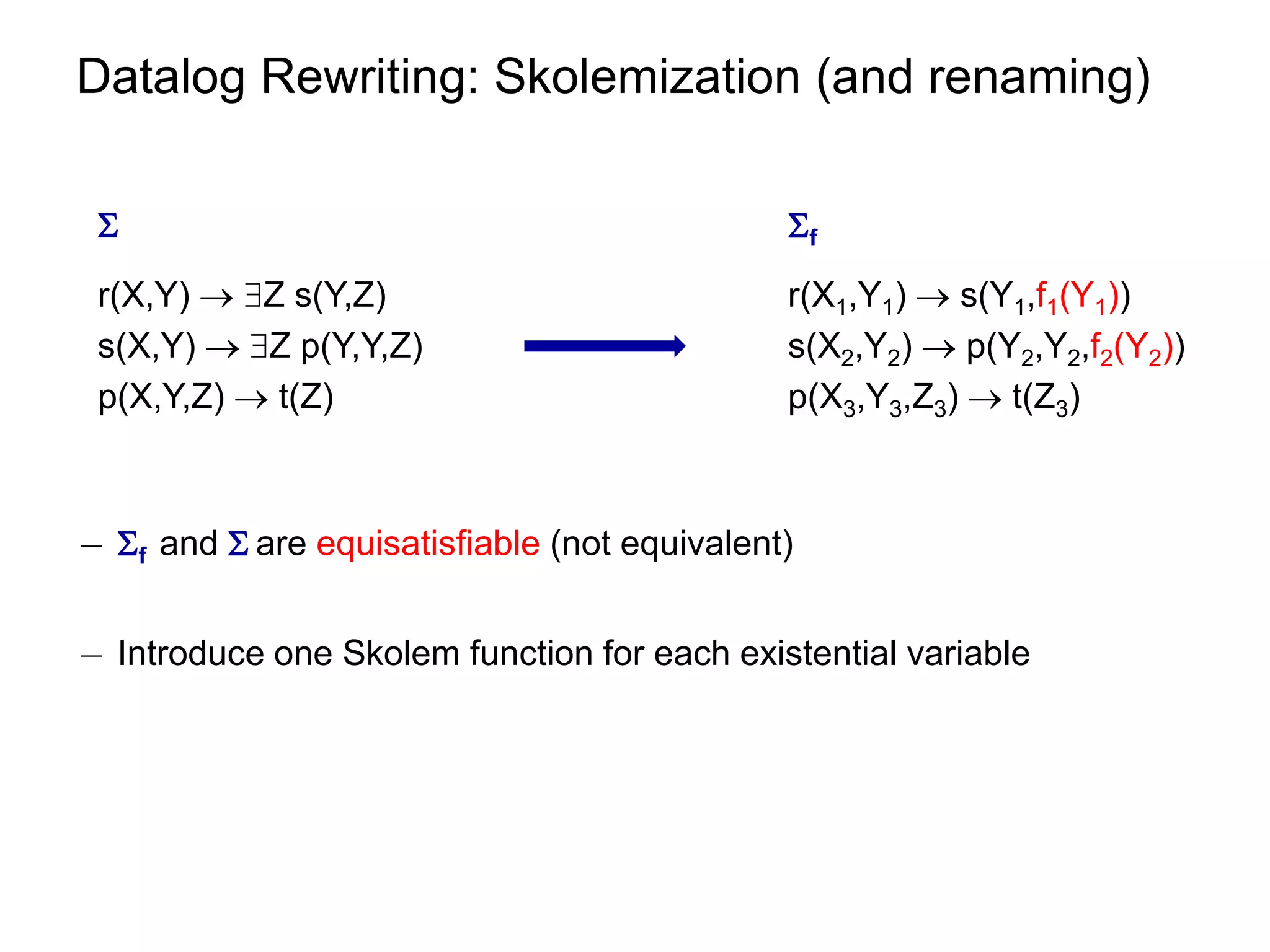

![Datalog Rewriting: Rule Saturation

¡ Apply resolution inference rule to rules in f

at least one of the rules contains Skolem terms

f [f]

δ1 : r (X1,Y1) s(Y1,f1(Y1)) …

δ2 : s(X2,Y2) p(Y2,Y2,f2(Y2)) r(X1,Y1) p(f1(Y1) ,f1(Y1), f2(f1(Y1)))

δ3 : p(X3,Y3,Z3) t(Z3) …](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-53-2048.jpg)

![Datalog Rewriting: Properties of Rule Saturation

¡ [f] mimics the chase derivations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-54-2048.jpg)

![Datalog Rewriting: Properties of Rule Saturation

¡ [f] mimics the chase derivations.

δ1 : r (X1,Y1) s(Y1,f1(Y1))

δ2 : s(X2,Y2) p(Y2,Y2,f2(Y2))

δ3 : p(X3,Y3,Z3) t(Z3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-55-2048.jpg)

![Datalog Rewriting: Properties of Rule Saturation

¡ [f] mimics the chase derivations.

δ1 : r (X1,Y1) s(Y1,f1(Y1))

δ2 : s(X2,Y2) p(Y2,Y2,f2(Y2))

δ3 : p(X3,Y3,Z3) t(Z3)

¡ [f] depends only on .

¡ [f] is possibly infinite

linear TGDs have BDDP: suffices to construct it up to k steps [f]k.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-56-2048.jpg)

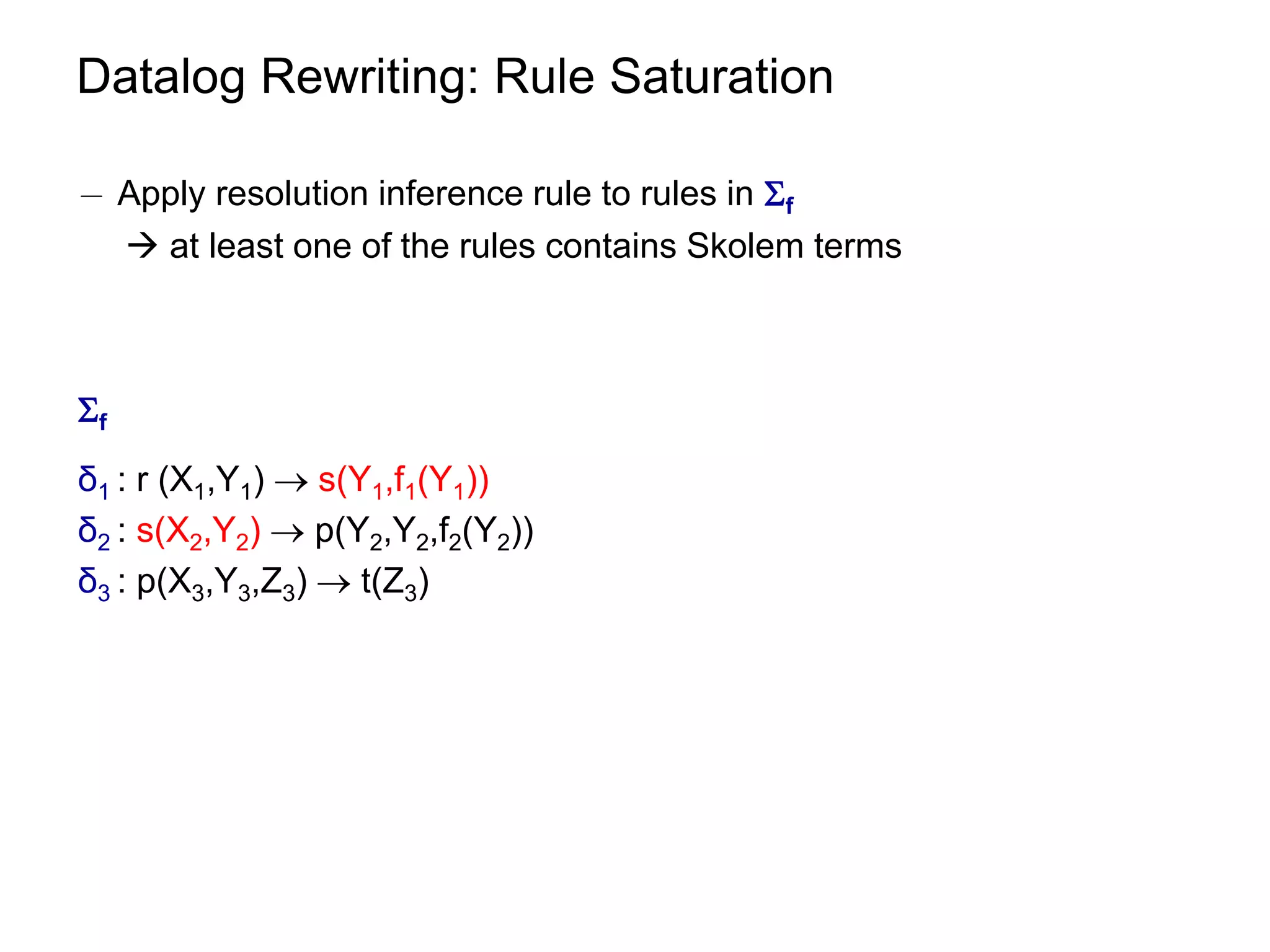

![Datalog Rewriting: Query Saturation

¡ resolve [f] with the query Q.

use only rules with Skolem terms.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-57-2048.jpg)

![Datalog Rewriting: Query Saturation

¡ resolve [f] with the query Q.

use only rules with Skolem terms.

[f] … Q

Q s(A,B), p(B,B,C)

δ1 : r (X1,Y1) s(Y1,f1(Y1))

δ2 : s(X2,Y2) p(Y2,Y2,f2(Y2))

δ3 : p(X3,Y3,Z3) t(Z3)

…

[δ12]] : r (X1,Y1) p(f1(Y1) ,f1(Y1), f2(f1(Y1)))

…

…

[Q,f] Q r(X1,Y1), p(f1(Y1), f1(Y1),C)

…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-58-2048.jpg)

![Datalog Rewriting: Query Saturation

¡ bypasses chase derivations with function symbols

Q

Q s(A,B), p(B,B,C)

[f] …

δ1 : r (X1,Y1) s(Y1,f1(Y1))

δ2 : s(X2,Y2) p(Y2,Y2,f2(Y2))

δ3 : p(X3,Y3,Z3) t(Z3)

…

[δ12]] : r (X1,Y1) p(f1(Y1) ,f1(Y1), f2(f1(Y1)))

…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-59-2048.jpg)

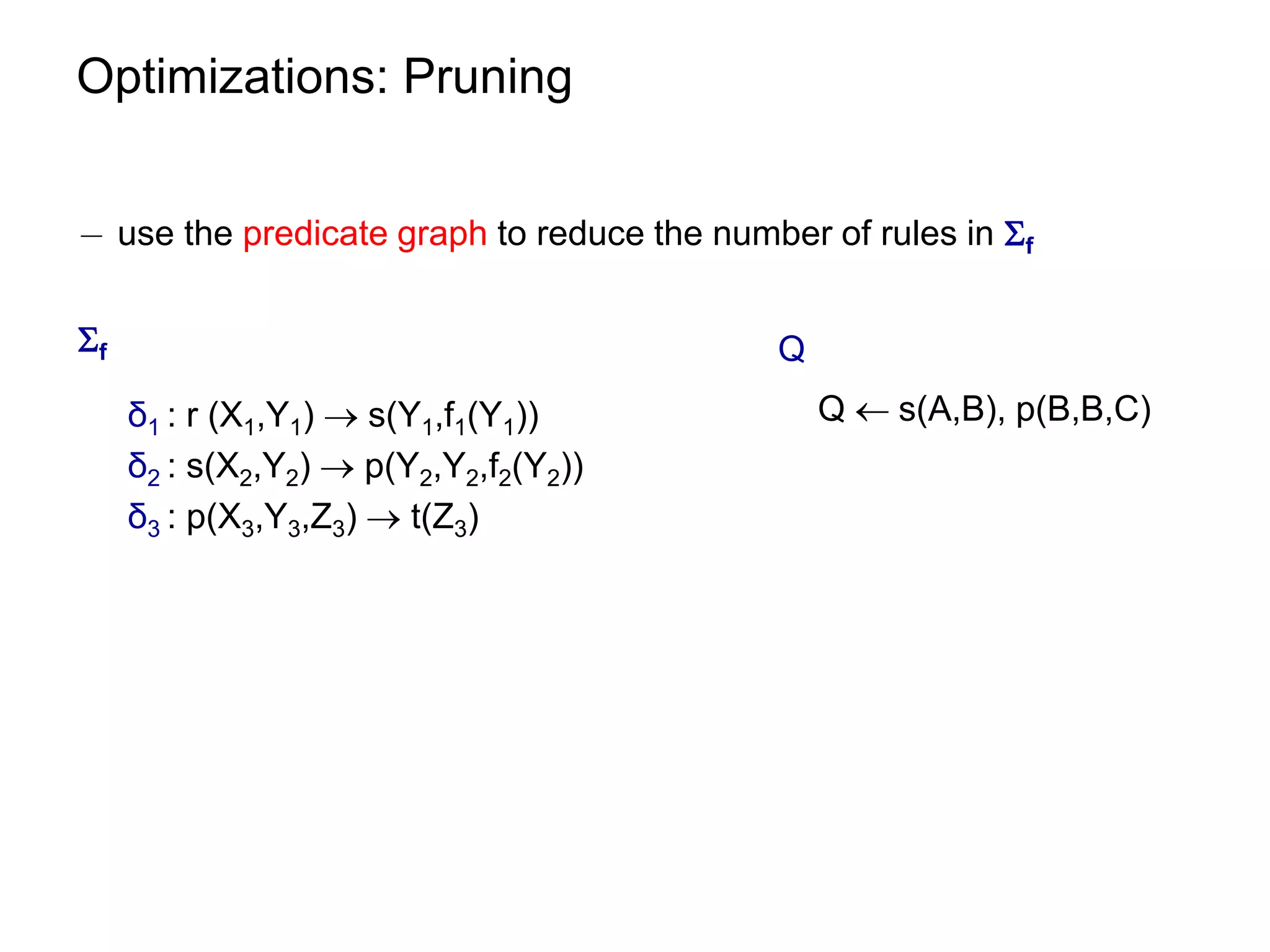

![Datalog Rewriting: Finalization

¡ keep only the function-free rules from [f] [ [Q,f]

¡ derivations producing certain answers are captured by function-

symbol-free rules.

¡ (optional) add auxiliary rules to make the rewriting a proper Datalog

query i.e., clear distinction IDB/EDB.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-60-2048.jpg)

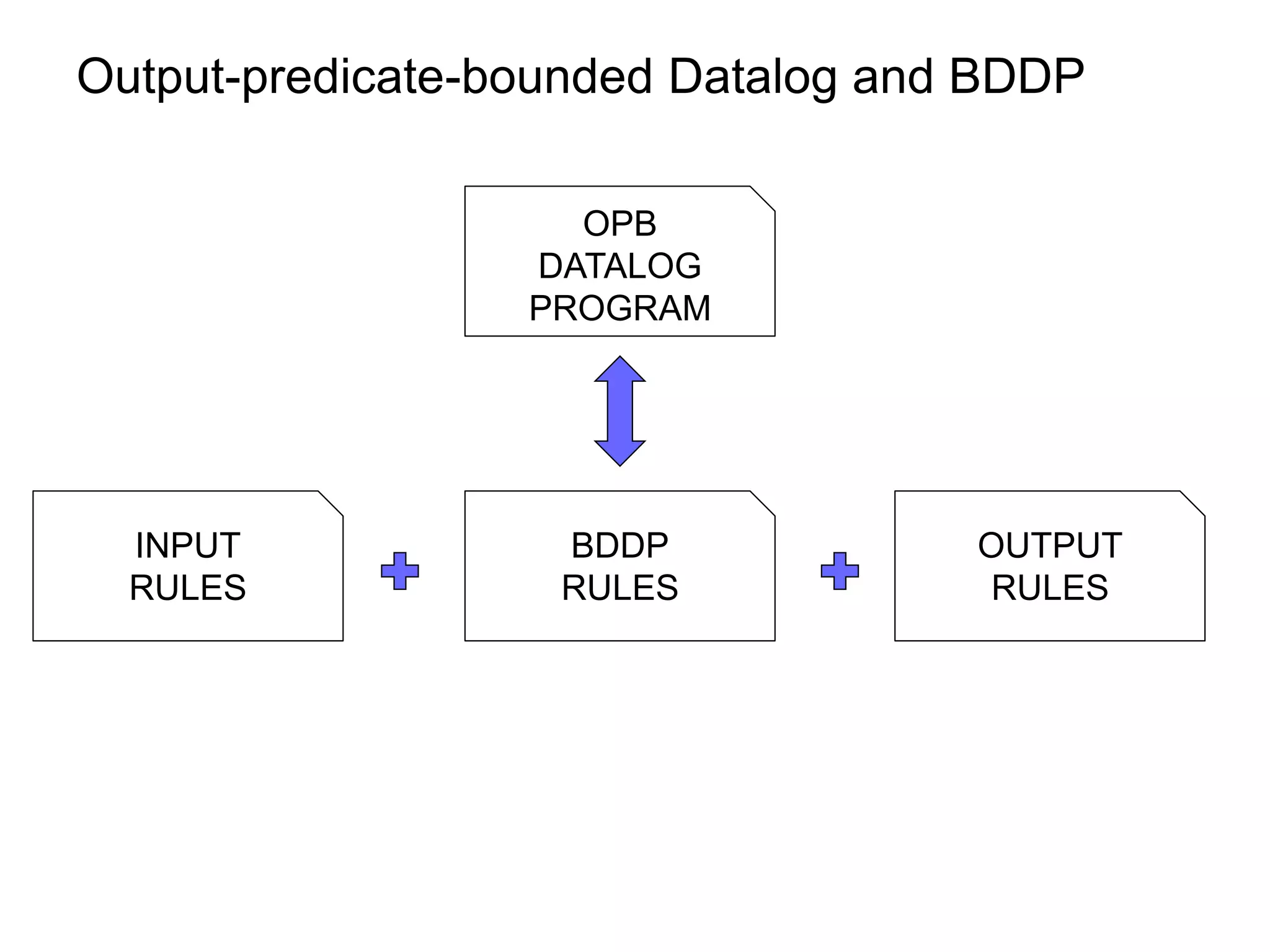

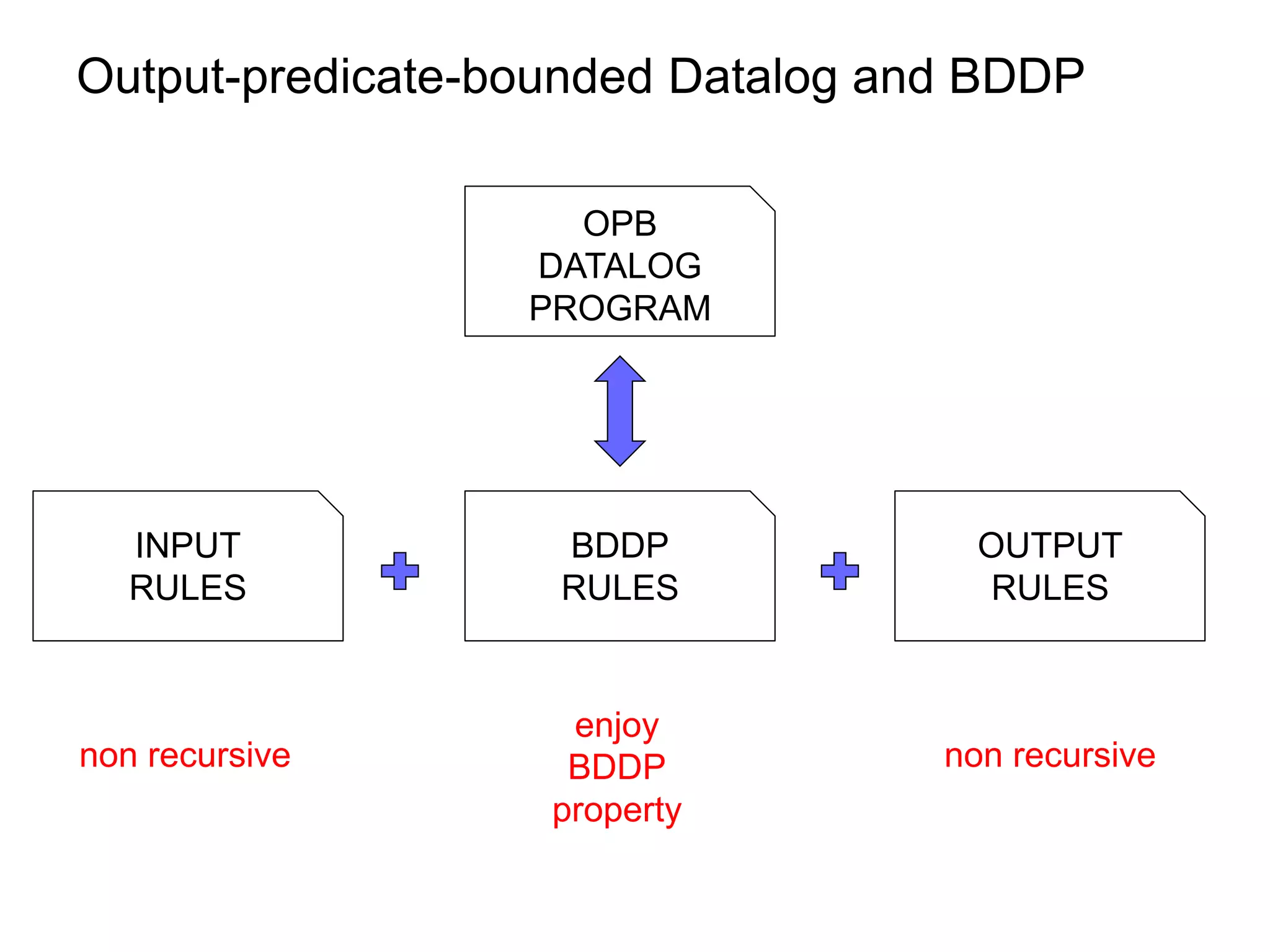

![OPB-Datalog and BDDP revisited

OPB

DATALOG

PROGRAM

INPUT BDDP OUTPUT

RULES RULES RULES

aux ff([f]) ff([Q,f])

enjoy

non recursive BDDP non recursive

property](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-61-2048.jpg)

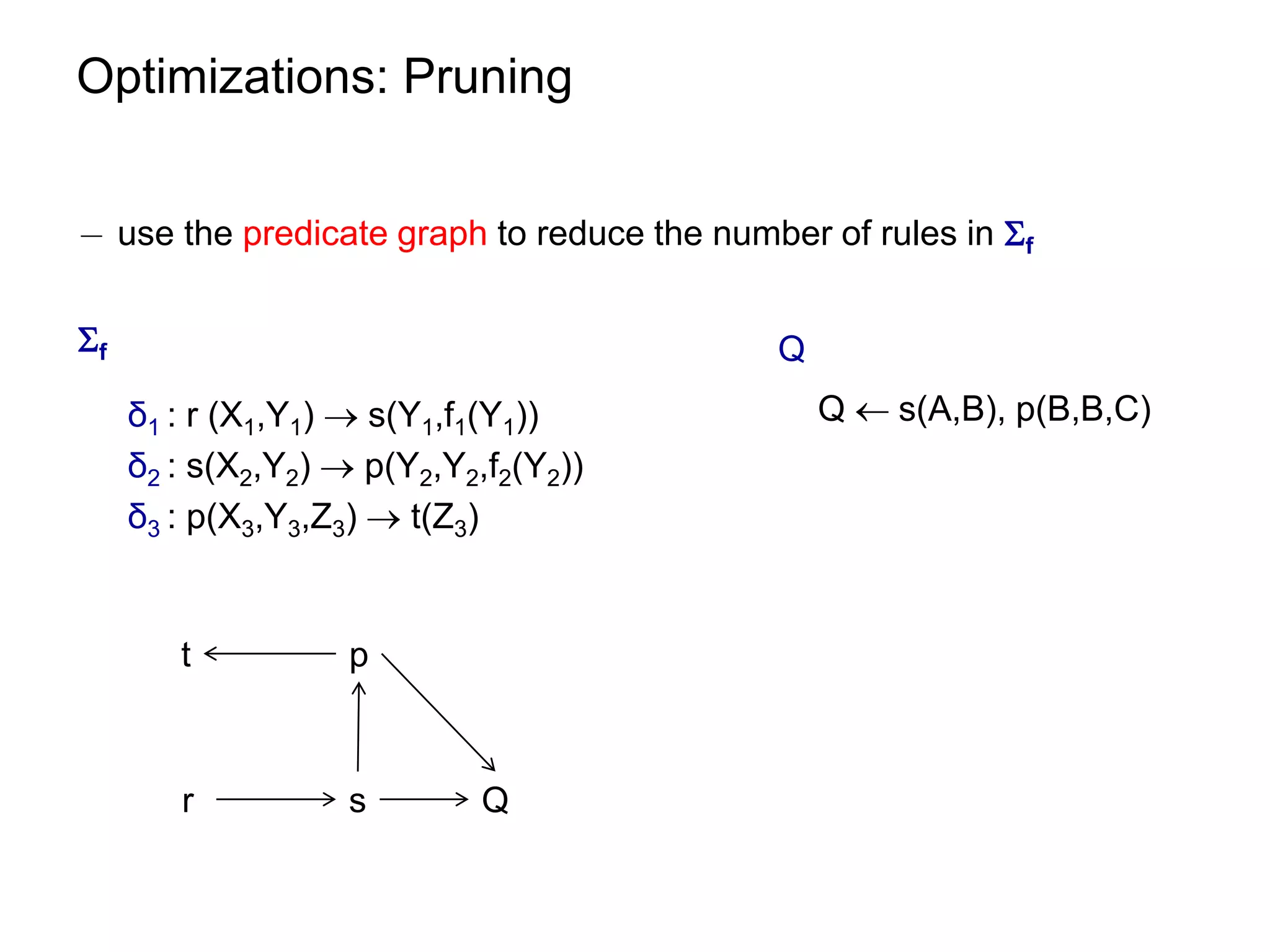

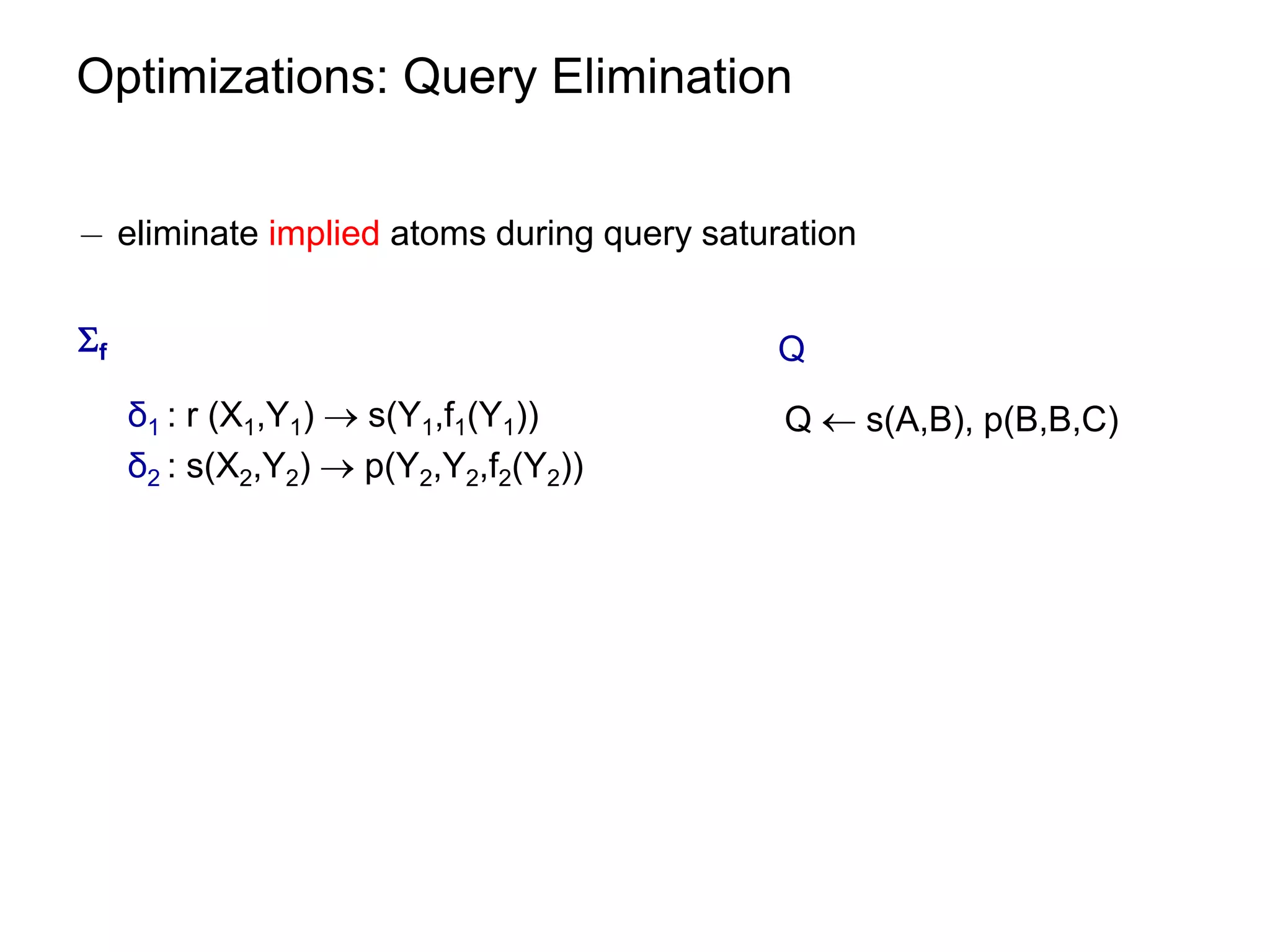

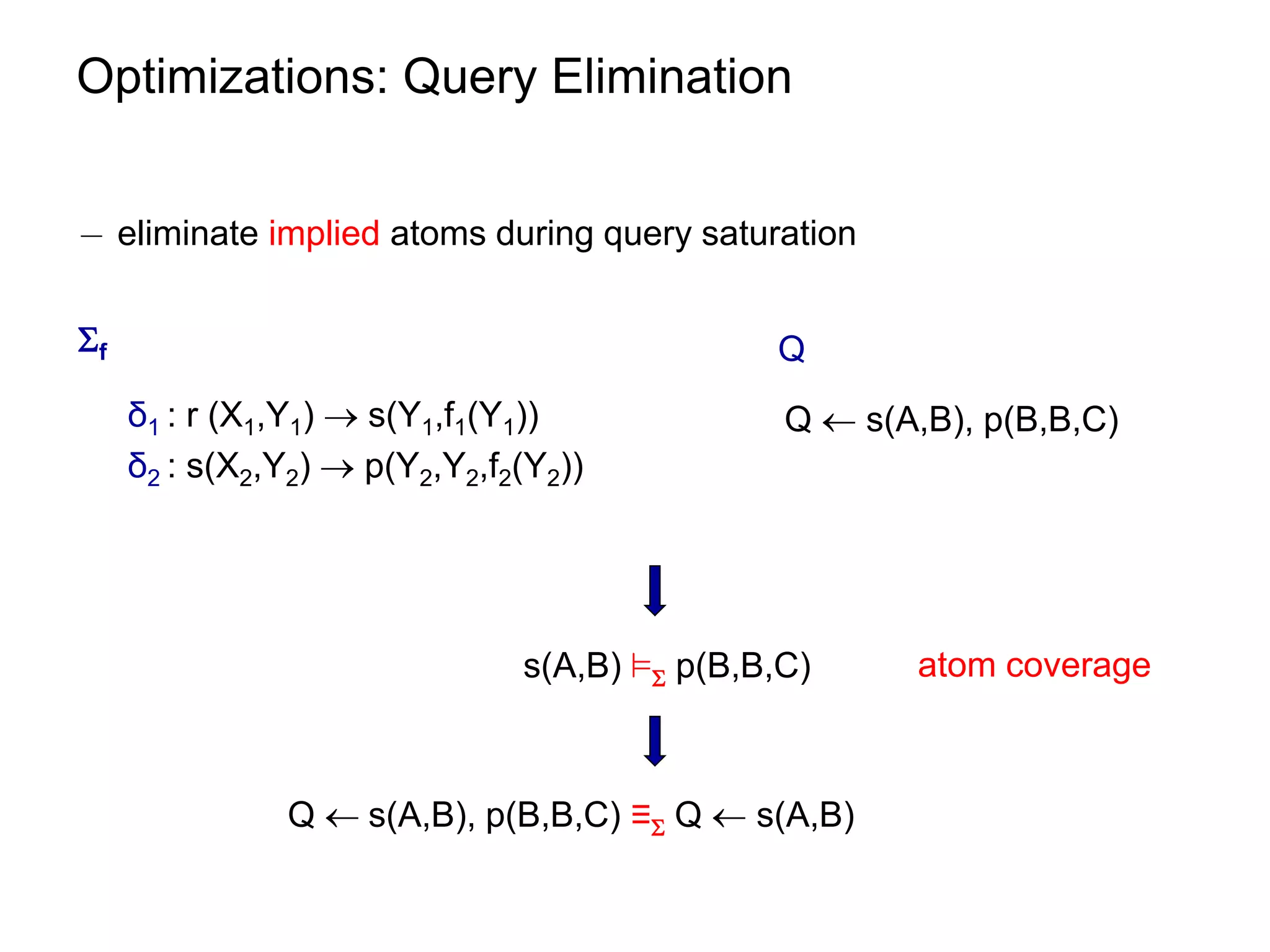

![Optimizations: Query Elimination

¡ atom coverage under linear TGDs can be checked in polynomial time

see paper.

¡ unique elimination strategy (w.r.t. the number of eliminated atoms)

see paper.

¡ given m = |body(ρ)| and n = ||

worst-case size of [f] [ [Q,f] is O((n∙m)m)

worst-case size of Q = <q,π > is O(n+m)m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-69-2048.jpg)

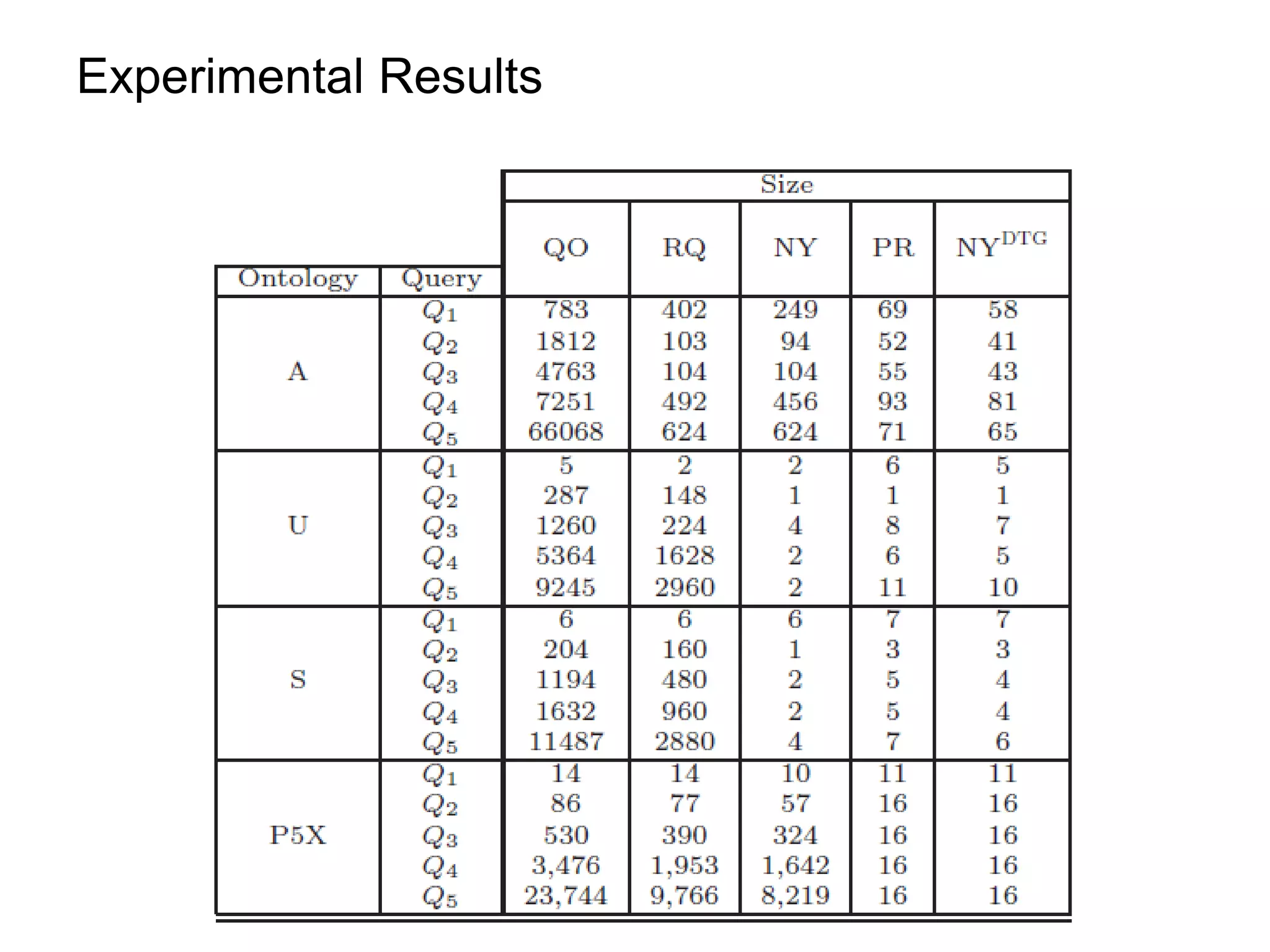

![Discussion

¡ Datalog rewriting is substantially more compact than UCQ rewriting.

¡ Does Datalog improve the end-to-end performance?

¡ Extend the procedure to larger classes of TGDs

guarded TGDs [Cali’ et Al, PODS 09] non FO-rewritable

sticky-join TGDs [Cali’ et Al, VLDB 10]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/orsivldb11-13154779239988-phpapp01-110908053319-phpapp01/75/Orsi-Vldb11-71-2048.jpg)