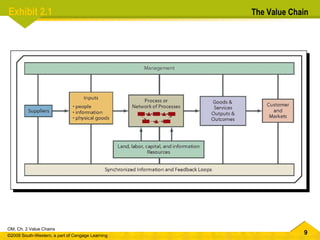

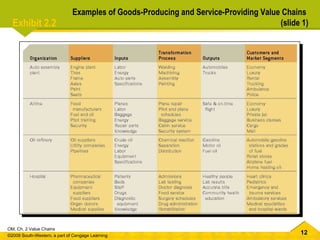

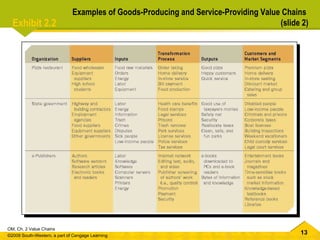

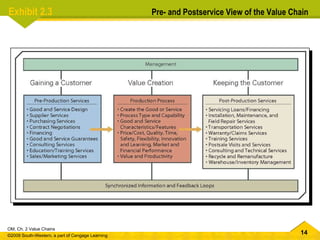

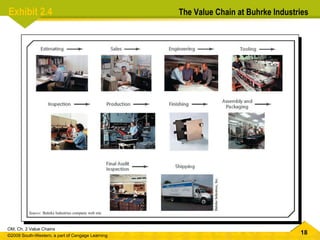

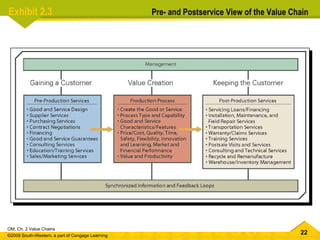

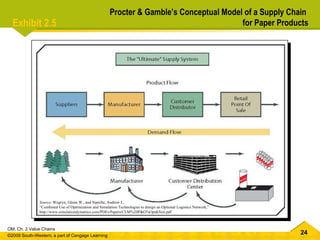

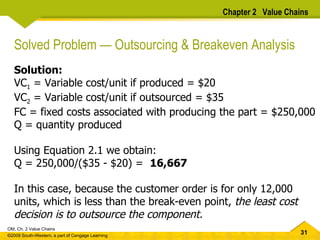

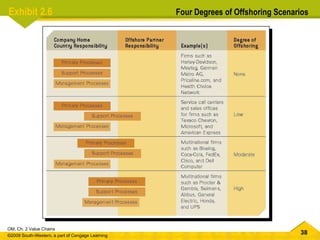

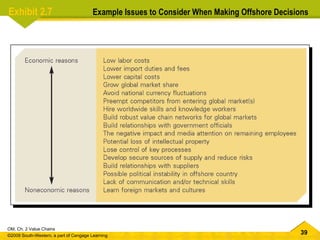

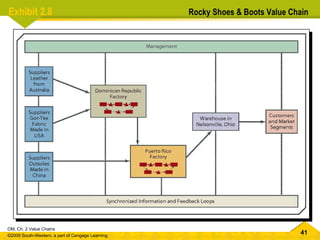

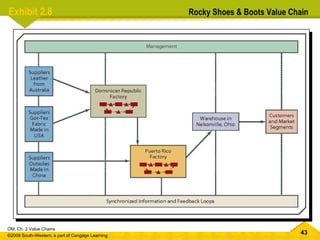

The document discusses value chains and supply chains. It defines key terms like value, value chain, supply chain, offshoring, and globalization. It also provides examples of companies' value chains, including Procter & Gamble, Buhrke Industries, Nestle, and Rocky Shoes & Boots. Managing global value chains is more complex due to issues like risk, transportation, purchasing, and legal/regulatory differences between countries.