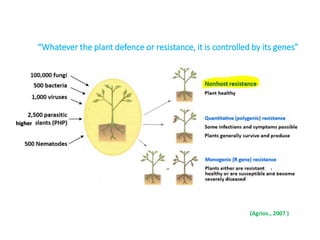

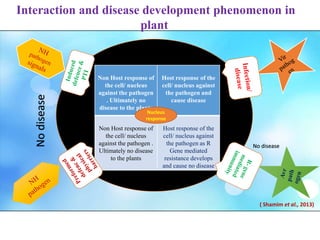

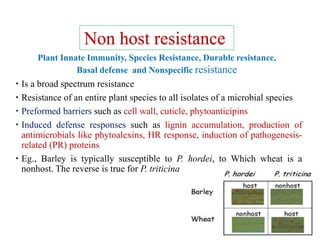

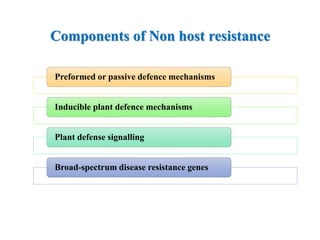

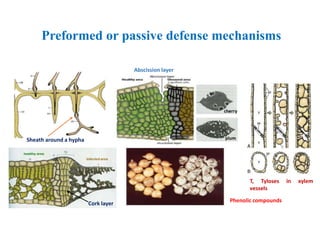

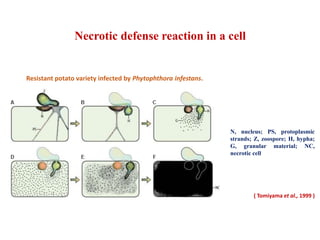

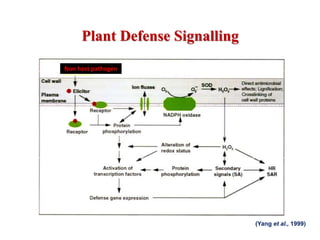

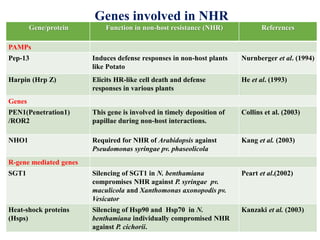

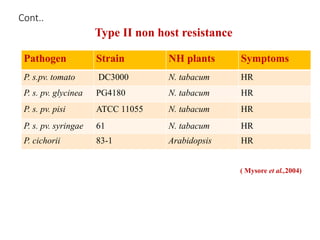

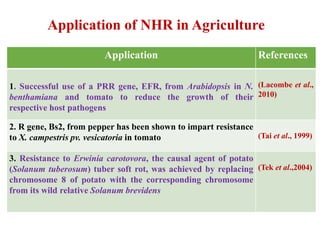

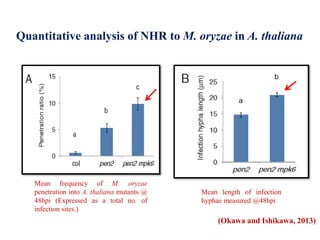

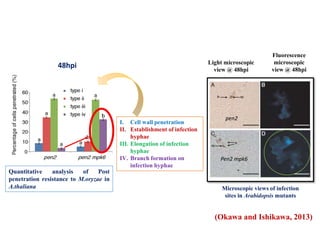

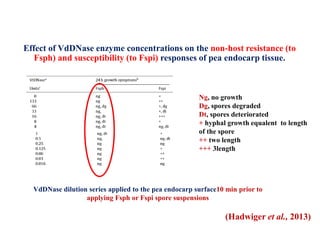

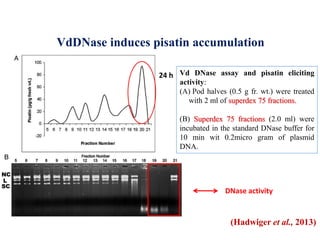

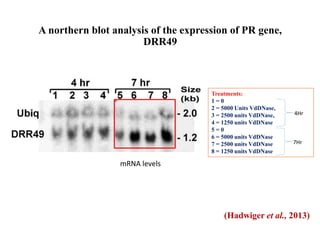

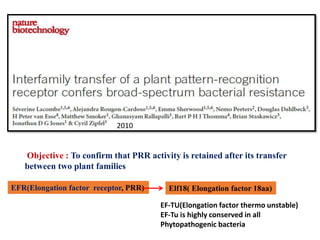

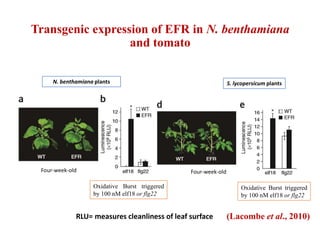

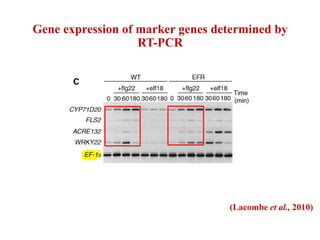

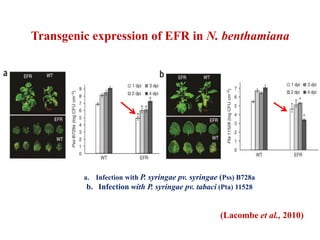

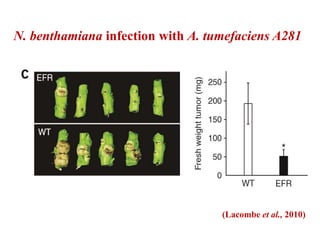

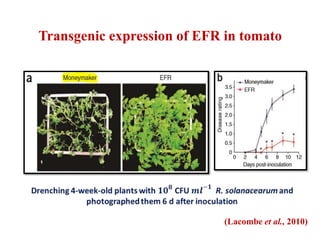

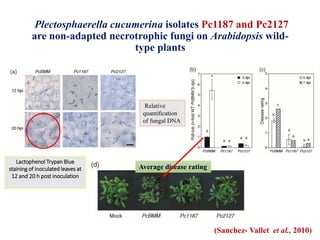

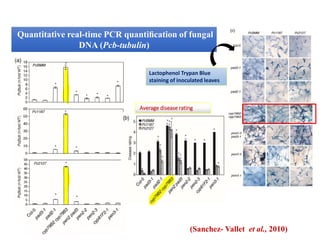

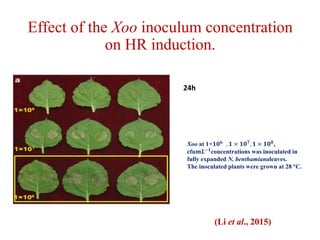

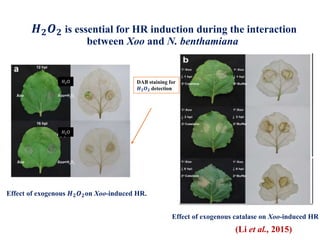

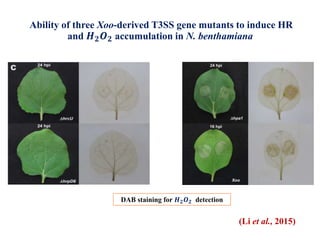

This document discusses non-host resistance in plants. It begins with an introduction and outline. It then discusses the components of non-host resistance, including preformed defenses, inducible defenses, defense signaling, and broad-spectrum resistance genes. It provides examples of different types of non-host resistance and applications in agriculture. The document also summarizes several studies examining the role of specific genes and signaling molecules in non-host resistance through experiments in model plants like Arabidopsis.