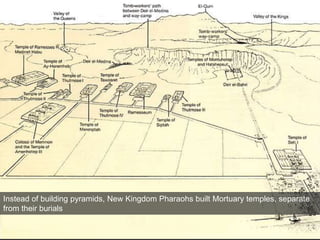

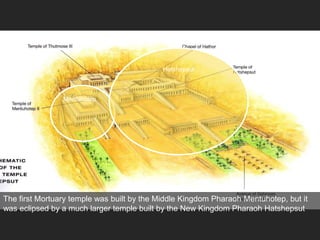

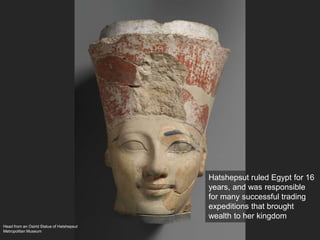

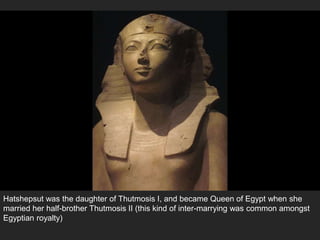

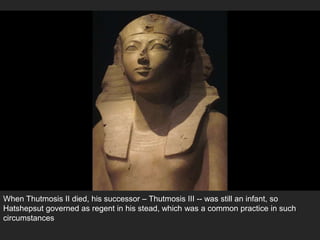

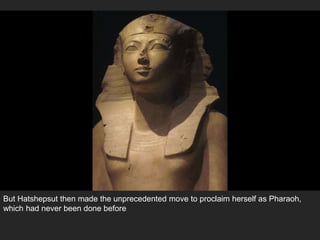

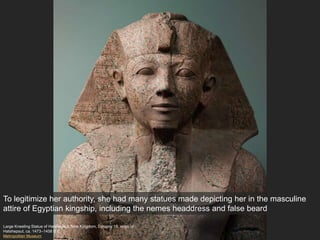

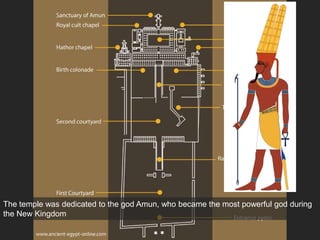

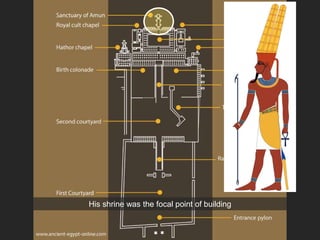

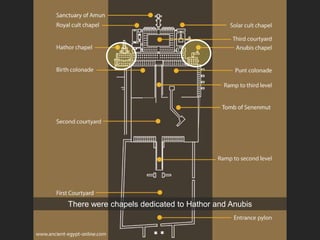

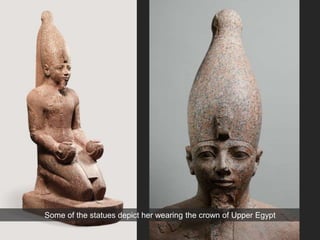

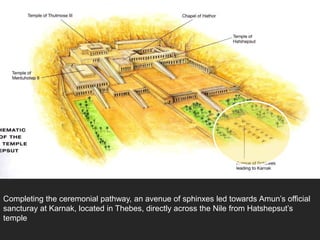

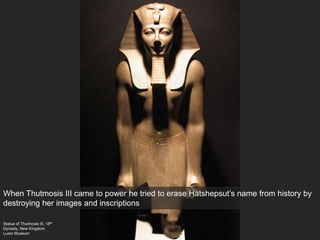

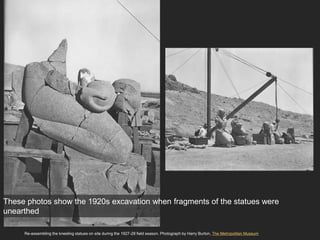

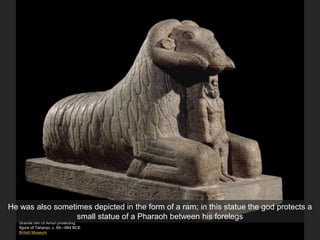

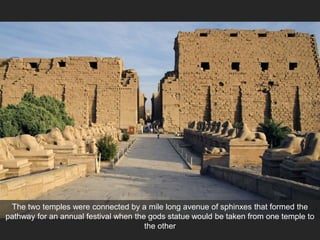

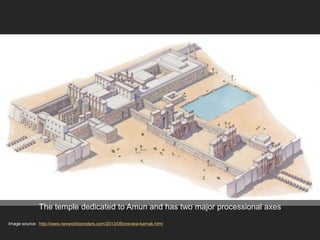

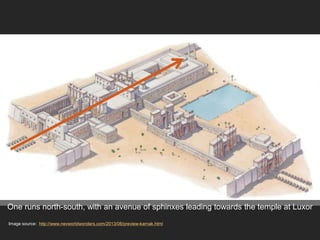

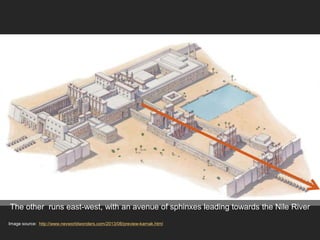

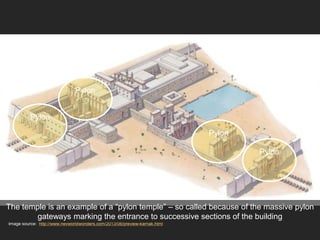

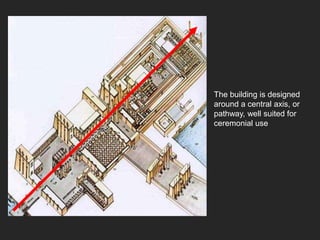

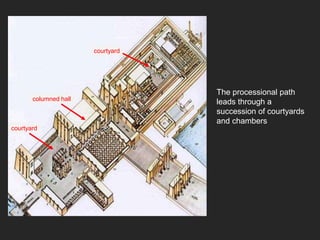

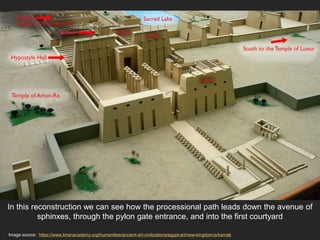

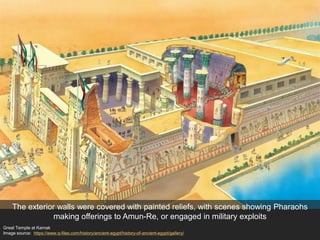

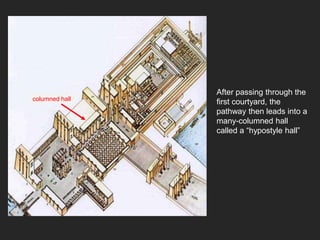

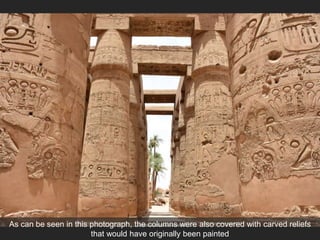

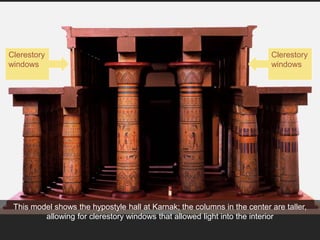

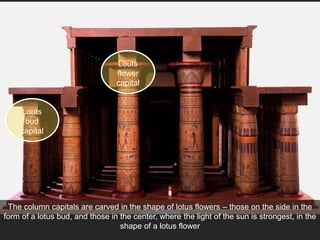

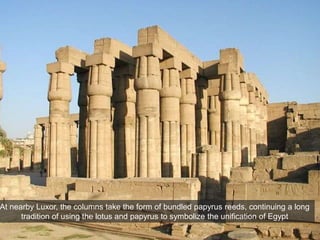

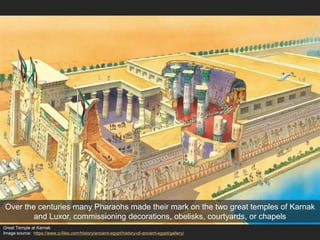

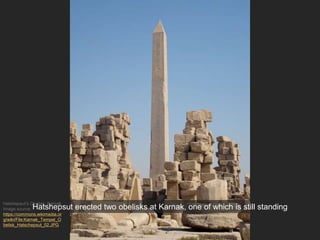

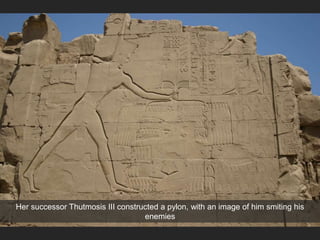

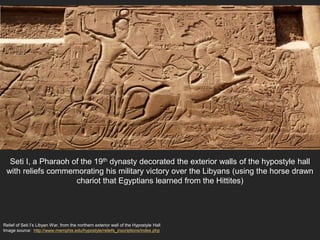

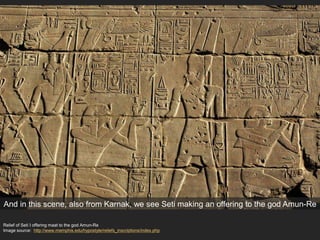

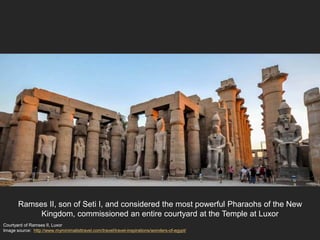

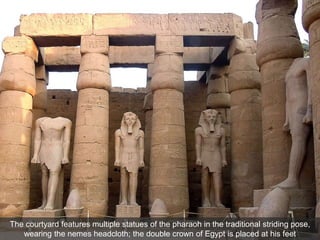

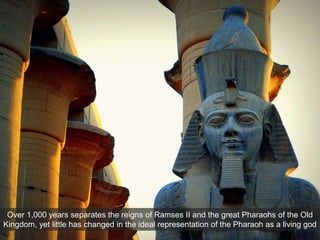

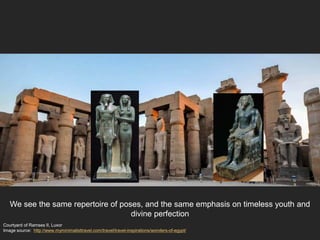

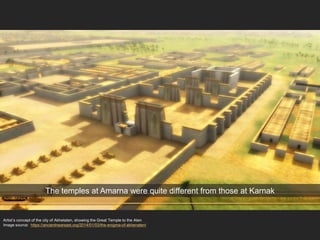

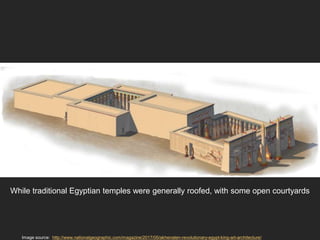

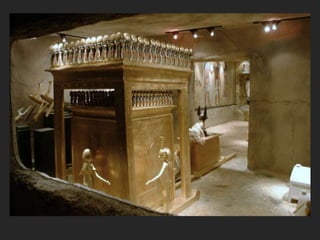

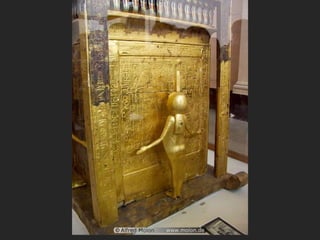

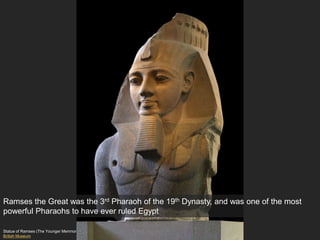

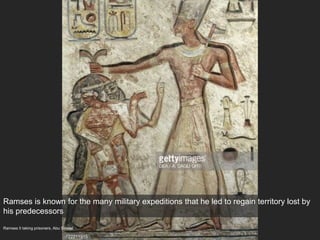

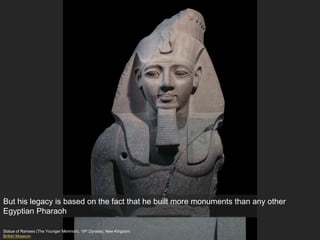

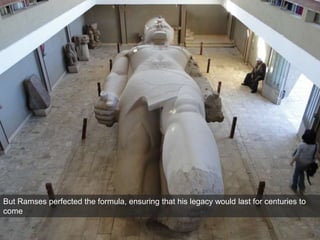

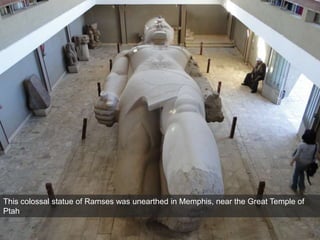

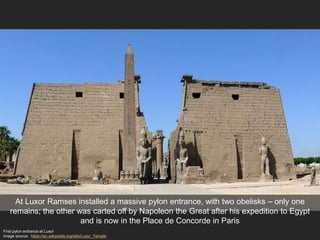

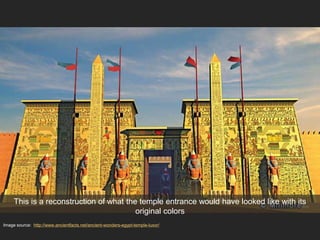

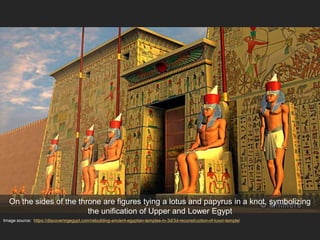

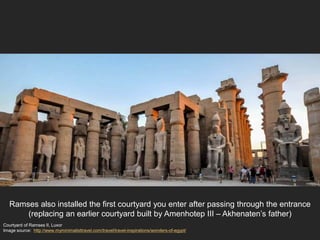

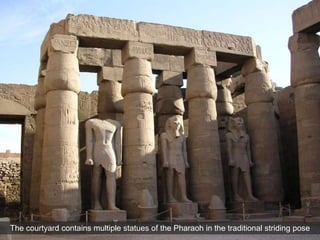

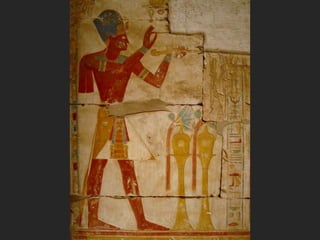

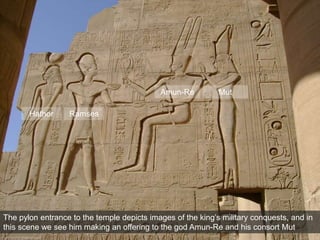

The document provides information about temples in New Kingdom Egypt. It describes how the god Amun-Re became the most powerful deity and his main sanctuaries were located at the Karnak and Luxor temple complexes in Thebes. The Karnak temple complex, one of the largest religious sites in the world, consisted of large courtyards and hypostyle halls connected by processional pathways. Over centuries, pharaohs like Hatshepsut, Thutmoses III, Seti I, and Ramses II added structures, decorations, and monuments to honor Amun-Re at the Karnak and Luxor temple sites.