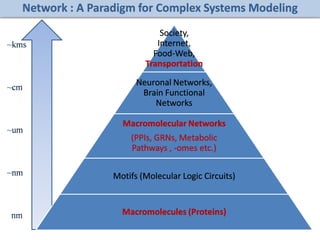

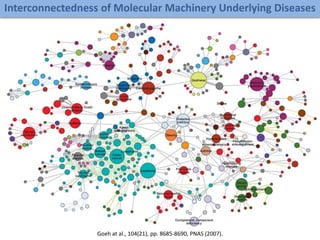

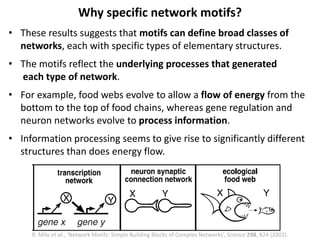

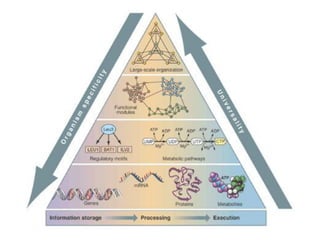

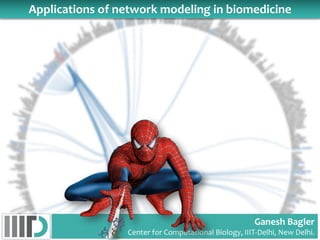

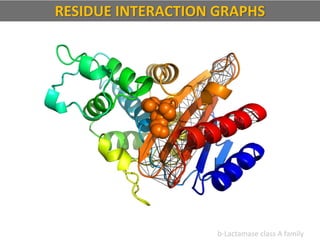

The document discusses network biology as a framework for modeling complex biological systems, emphasizing the importance of understanding biological entities as interconnected networks. It highlights various applications such as protein structure prediction, gene identification, and disease modeling through graph theory and network models. Additionally, it explores concepts like small-world networks, scale-free networks, and network motifs, along with their implications for biomedical research and the importance of integrative models in biology.

![Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]

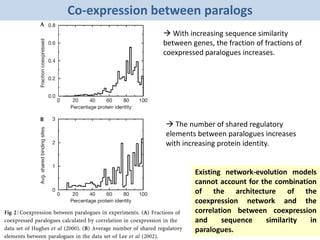

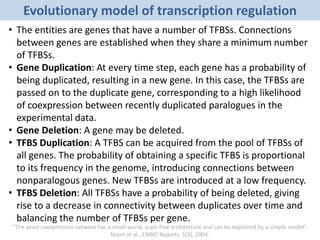

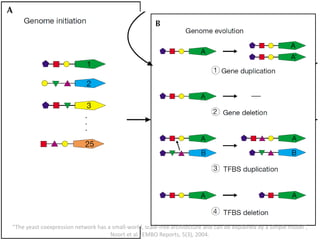

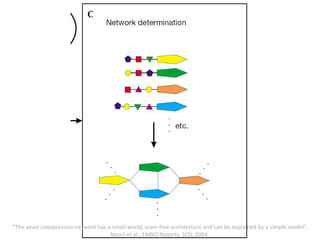

Vinay Randhawa and Ganesh Bagler*, OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology, 16 (10) , 2012.

V Randhawa, P Sharma, S Bhushan and G Bagler*, OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology, 17(6), 302-317 (2013).

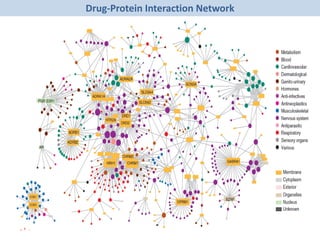

A rational approach towards ‘complex diseases’.

Data: KEGG, OMIM, PubMed, protein interactomes, gene regulations, expression data.

Network Models of Complex Diseases

Molecular interactomes of diseases phenotypes: Modeling and control

Why

What

How

model

Interactomes,

Expression data

control

targets, drugs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-27-320.jpg)

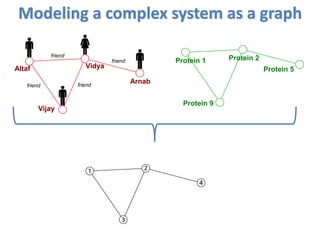

![Modeling a complex system as a graph

Undirected Network Directed Network

[DEFN] Degree: Number of nodes connected to a given node.

A

B

C

D

E

F G

A

B

C

D

E

F G

k_A=2; k_B=3 k_A_in=1; k_A_out=1;

k_B_in=3; k_B_in=1;

Weighted and Un-weighted Networks](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-37-320.jpg)

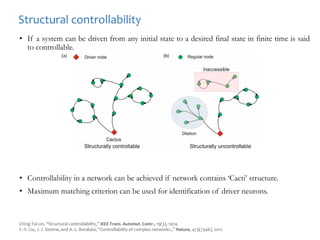

![Identification of Generic Cancer Genes: Cancer Genes Network (CGN)

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]

• A protein interactome of interactions among cancer genes: Cancer Genes Network (CGN).

• Databases: CancerGenes Database, Human Protein Reference Database, KEGG-PIC.

• Central genes were identified using ‘degree’, ‘betweenness’ and ‘stress’ metrics.

11602 interactions

among 2665

cancer proteins](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-78-320.jpg)

![Cancer Genes Network : Generic and Specific Cancer Genes

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]

11602 interactions

among 2665

cancer proteins](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-79-320.jpg)

![● % Overlap of Central Genes in

‘Cancer Genes Network’ with

‘KEGG Pathways-in-Cancer’

Random Samplings

Negative Controls

The hubs and bottlenecks of ‘Cancer Genes Network’ represent

genes that are involved in generic cancer mechanisms.

Genes Central to ‘Cancer Genes Network’ match with KEGG-PIC

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-80-320.jpg)

![Hub Genes Random Samplings

1,2,3: Degree, Betweenness, Stress

4,5: Neighborhood connectivity,

Topological coefficient

6,7 (data not shown): Clustering coeff.,

Average shortest path length

Around 50% of a total 2665 cancer

genes of CGN, were ‘essential (1315)’.

Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI)

Phenotype Data.

Hubs of Cancer Genes Network (CGN) are ‘Biologically Essential’

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-81-320.jpg)

![Strategy for Identification of Targets Specific to Secondary Bone Cancer

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-82-320.jpg)

![(A) (B)

(C)

Subsets comprising

targets specific to

‘Secondary Bone

Cancer’

Identification of Targets Specific to Secondary Bone Cancer

Shikha Vashisht and Ganesh Bagler*, 7(11): e49401, PLoS ONE (2012). arXiv:1112.1510v2 [q-bio.MN]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-83-320.jpg)

![Folding

Time

kF [sec-1]ln (kF)

7.389 s0.1353-2

1 s1.000

0.1353 s7.392

18.32 ms54.604

2.479 ms403.436

33.55 ms2,981.008

0.4540 s22,026.0010

6.144 s16275.4712

RATE OF FOLDING—FOLDING TIME

Bagler and Sinha, Bioinformatics (2007)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/networksinbiosystemsdibrugarhgbagler-180107033126/85/Network-Biology-A-paradigm-for-modeling-biological-complex-systems-98-320.jpg)