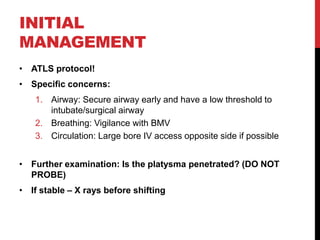

A 35-year-old male presented with a stab wound to the neck. He had a 5-cm neck wound with an expanding hematoma. His vitals showed a blood pressure of 86/46, heart rate of 140, and oxygen saturation of 95%.

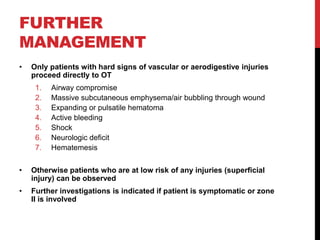

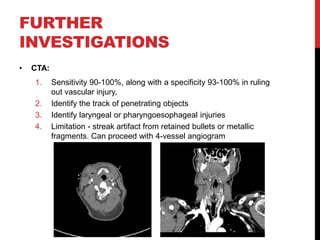

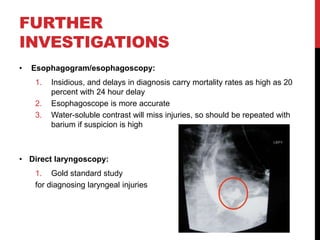

Penetrating neck trauma requires rapid assessment and management to address threats to the airway, breathing, and circulation. Exploration of the neck is usually warranted for injuries in zone II to identify damage to major blood vessels or the aerodigestive tract. Investigation with CT angiography can help identify vascular injuries while esophagoscopy evaluates the esophagus. Surgical exploration may be needed for active bleeding, expanding hematomas, or signs of injuries to the air