The document is a seminar presentation on nano-priming, a technique involving the application of nanoparticles to improve seed germination and plant growth in medicinal and aromatic plants. It covers the history, various priming methods, and details the effects of biologically synthesized nanoparticles on seed germination, seedling growth, and physiological changes in plants. Several case studies are included, illustrating the successful application of nano-priming with different nanoparticles across various plant species.

![Table 1. Influence of nano-priming plant growth and metabolism

Effect on plant physiology Changes in chemical

constituents

Molecular changes in

plant

Growth & biomass,

Photosynthesis [Chlorophyll]

Photosynthetic quantum efficiency,

Gas exchange traits,

Carotenoids,

Cellular electron exchange,

Soluble proteins,

Relative water content,

Antioxidant enzymes [POX, SOD,

CAT & APX]

Gibberellic acid

IAA

ABA:GA

α-amylase

Soluble sugar

Aquaporins

Lipids

DNA content

DNA repair

Cell wall extension (NtLRX1)

Cell division (CycB)

Aquaporin (PIP1, PIP2, NIP1, TIP3

& TIP4)

Phynylalanine ammonia lysase

(PAL1)

Anthocyanin synthase 1 (ANS1) and

Anthocyanin pigment 1 (PAP1)

11/48

Nile et al., 2022](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nano-priming-anemergingtechnologyinmedicinalandaromaticplants-240904113955-fa825d3f/75/Nano-priming-An-Emerging-technology-in-Medicinal-and-Aromatic-Plants-pptx-11-2048.jpg)

![Material and Methods

• Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles

• Seeds (Coated and uncoated) were imbibed in each concentration of chitosan

nanoparticles (CsNPs) (0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/ ml) for 4, 8 and 12 h

• Germination bioassay – Petri dish assay

• Growth experiment – In plastic pots

• Growth Parameters – Germination percentage, Gemination velocity, Speed

of germination, Germination energy, Germination index, Mean germination

time and Seedling vigour index

• Determination of plant biomass and water content

• Determination of phytochemicals [Alkaloid] – GC-MS

• Antioxidant activity

Allam et al., 2024 33/48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nano-priming-anemergingtechnologyinmedicinalandaromaticplants-240904113955-fa825d3f/75/Nano-priming-An-Emerging-technology-in-Medicinal-and-Aromatic-Plants-pptx-33-2048.jpg)

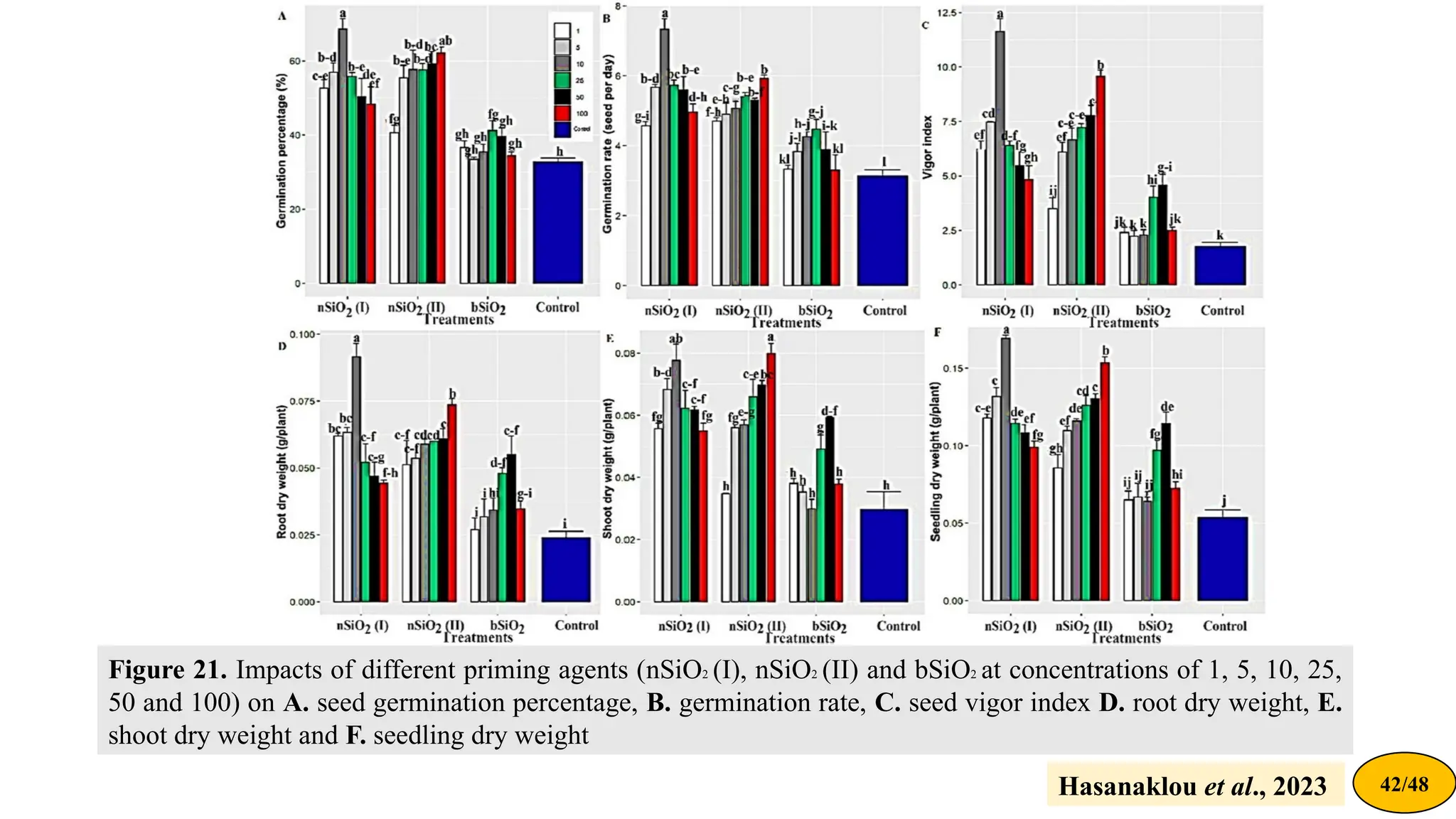

![Material and methods

• Synthesis of nanoparticles (nSiO2 (I) and nSiO2 (II) showed

the silica NPs synthesized at 85 °C and 25 °C, respectively)

• Seed treatment with different concentrations (0, 1, 5, 10, 25,

50, and 100 ppm) of nSiO2 (I), nSiO2 (II), and commercial

bulk SiO2 (bSiO2)

• Germination percentage, germination rate & seed vigour

• Starch and sucrose determination

• Antioxidant enzymes activity [CAT & POX]

Hasanaklou et al., 2023 41/48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nano-priming-anemergingtechnologyinmedicinalandaromaticplants-240904113955-fa825d3f/75/Nano-priming-An-Emerging-technology-in-Medicinal-and-Aromatic-Plants-pptx-41-2048.jpg)