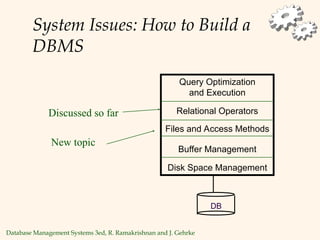

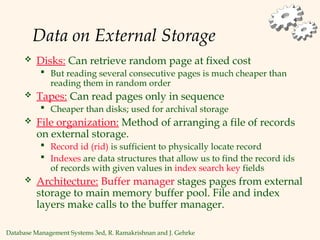

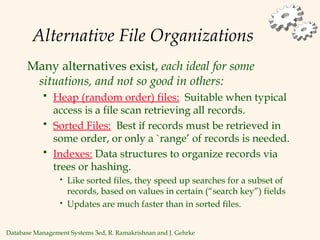

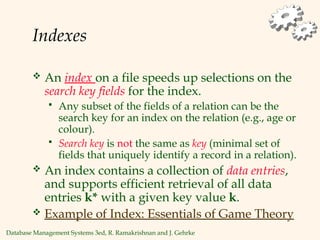

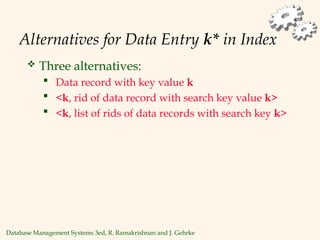

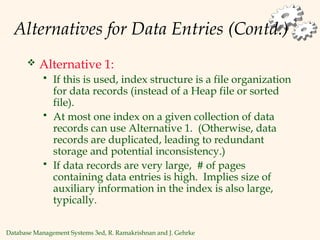

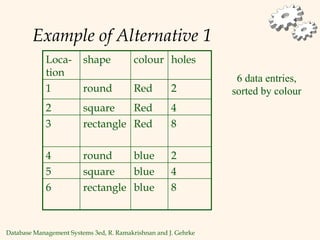

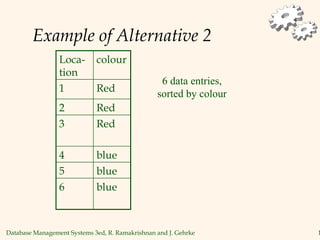

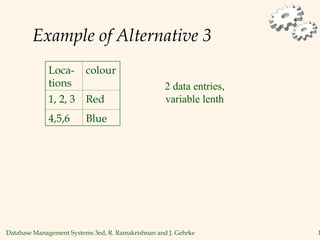

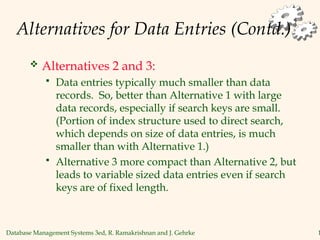

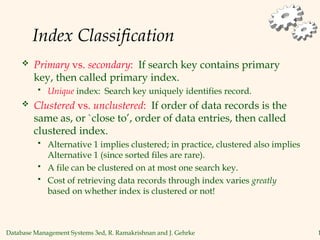

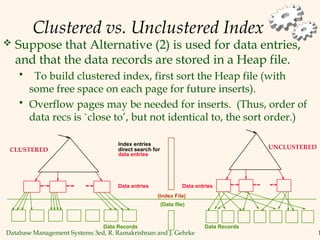

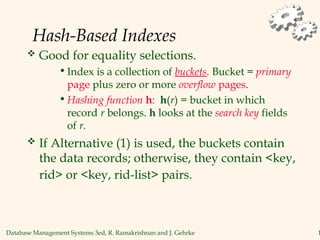

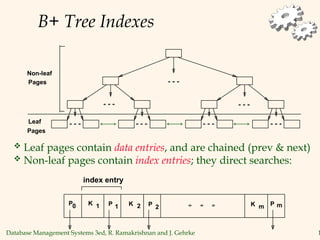

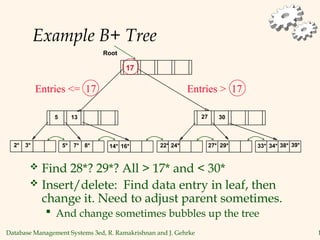

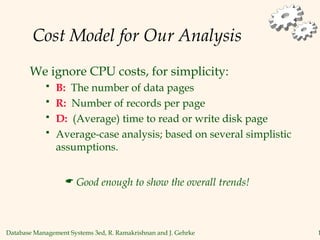

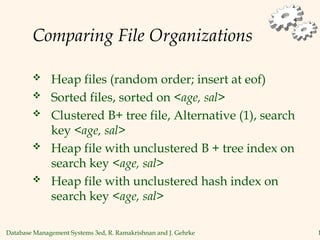

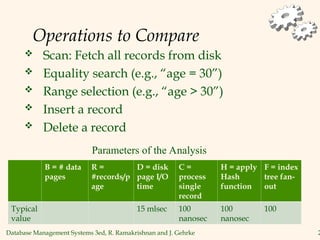

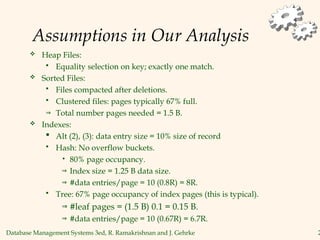

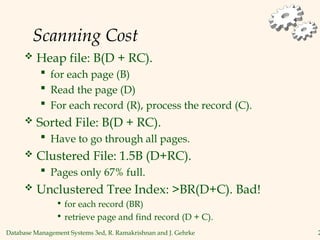

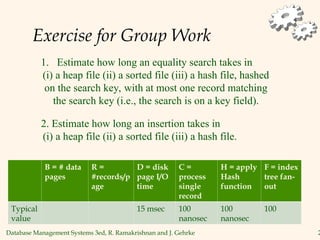

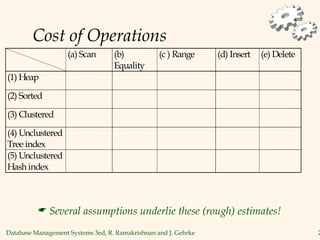

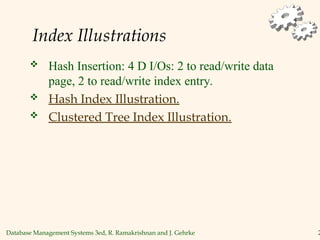

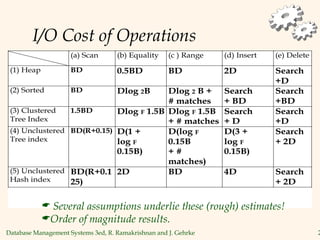

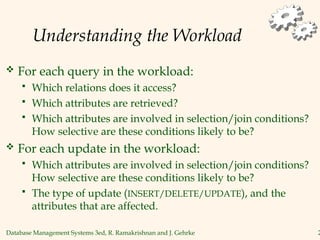

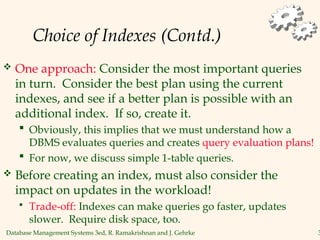

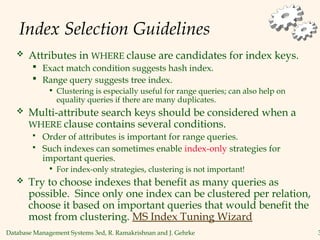

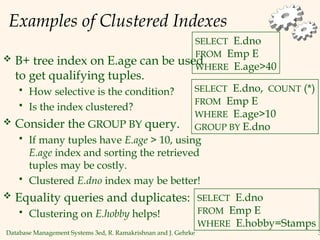

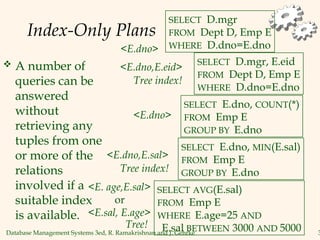

The document discusses database management systems, focusing on storage and indexing methods, including file organization techniques and their efficiencies. It highlights different types of indexes such as primary, secondary, clustered, and unclustered, and emphasizes the importance of choosing appropriate indexing strategies based on query types and workloads. Overall, it outlines the trade-offs in terms of speed and resource consumption involved with various indexing approaches and file organizations.