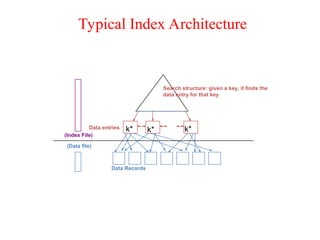

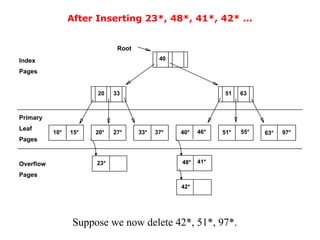

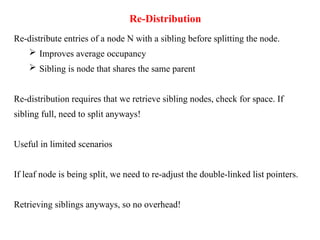

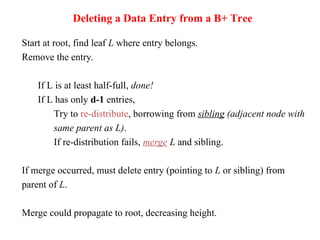

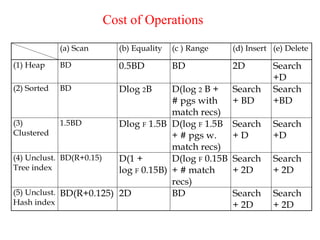

The document discusses file organization and indexing methods in database management systems, covering various indexing techniques including clustered and unclustered indexes, tree-based indexing, and hash-based indexing. It details data structures such as B+ trees and ISAM, explaining how they facilitate efficient data retrieval and management through structured record identification and access methods. Additionally, it compares different file organizational techniques and their impact on performance during operations like scanning, searching, inserting, and deleting records.

![Assignment - 6

1. List the physical storage media available on the computers that you use

routinely. Give the speed with which data can be accessed on each

mediaum.

2. Explain the distinction between closed and open hashing. Discuss the

relative merits of each technique in database applications.

3. Compare the Heap file organization and Sequential file organization. [16]

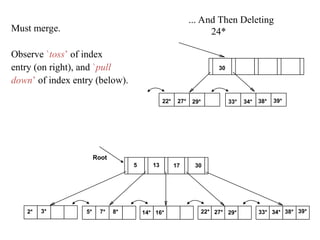

4. What are the intuitions for tree indexes? and Explain about ISAM.

5. What are the causes of bucket overflow in a hash file organization? What

can be done to reduce the occurrence of bucket overflows?

6. Suppose that we are using extendable hashing on a file that contains

records with the following search-key values: 2,3,5,7,11,17,19,23,29,31

Show the extendable hash structure for this file if the hash function is

h(x) = x mod 8 and buckets can hold three records.

7. Explain about the B+tree file organization in detail..

8. When is it preferable to use a dense index rather than a sparse index?

Explain your answer.

9. Since indices speed query processing, why might they not be kept on

several search keys? List as many reasons as possible.

10. Write briefly about Primary and secondary Indexes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dbms-unit-vi-250204083716-99370509/85/Database-Management-Systems-full-lecture-51-320.jpg)