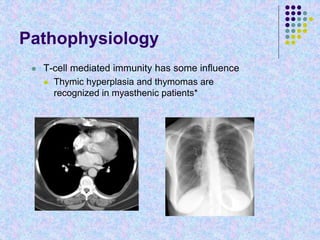

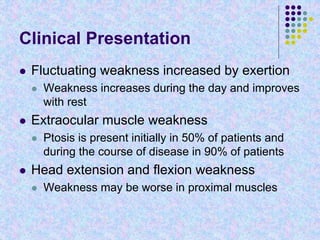

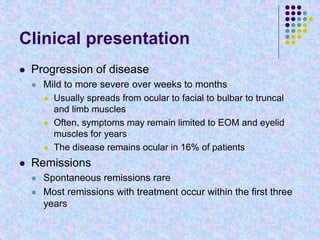

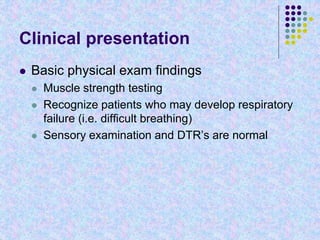

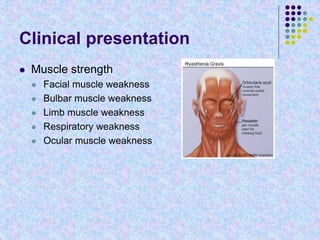

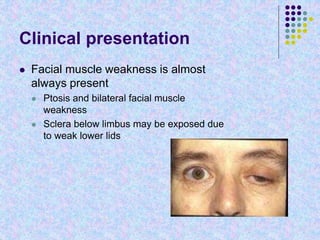

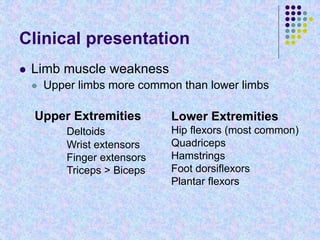

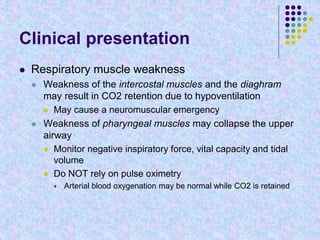

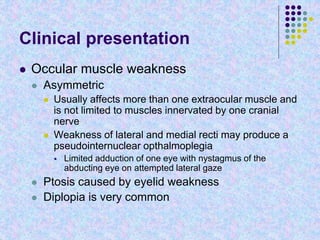

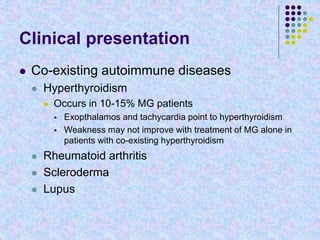

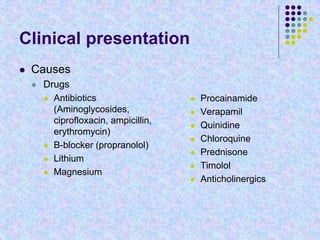

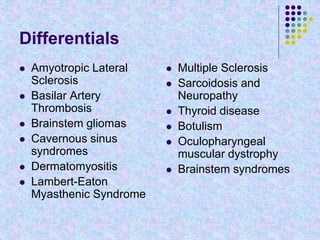

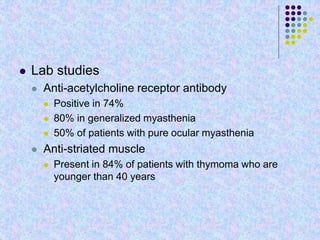

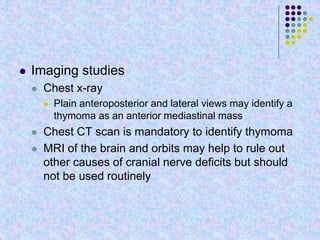

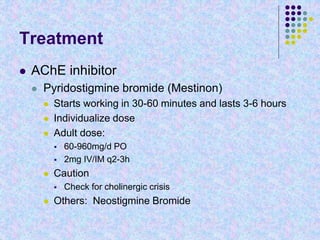

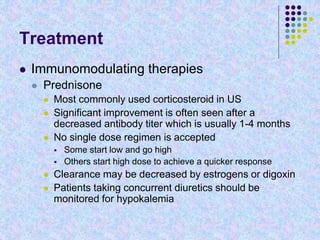

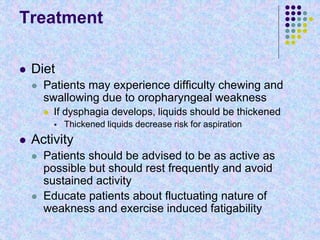

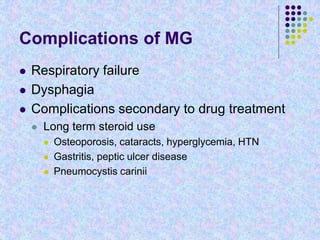

Myasthenia Gravis is an autoimmune disorder characterized by weakness in skeletal muscles that worsens with exertion and improves with rest. Antibodies are directed against acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction, reducing their numbers and impairing signal transmission. Clinical presentation includes weakness of ocular, facial, bulbar, and limb muscles. Diagnosis involves testing for acetylcholine receptor antibodies, repetitive nerve stimulation, and response to edrophonium. Treatment focuses on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, immunosuppression, and thymectomy in some cases.