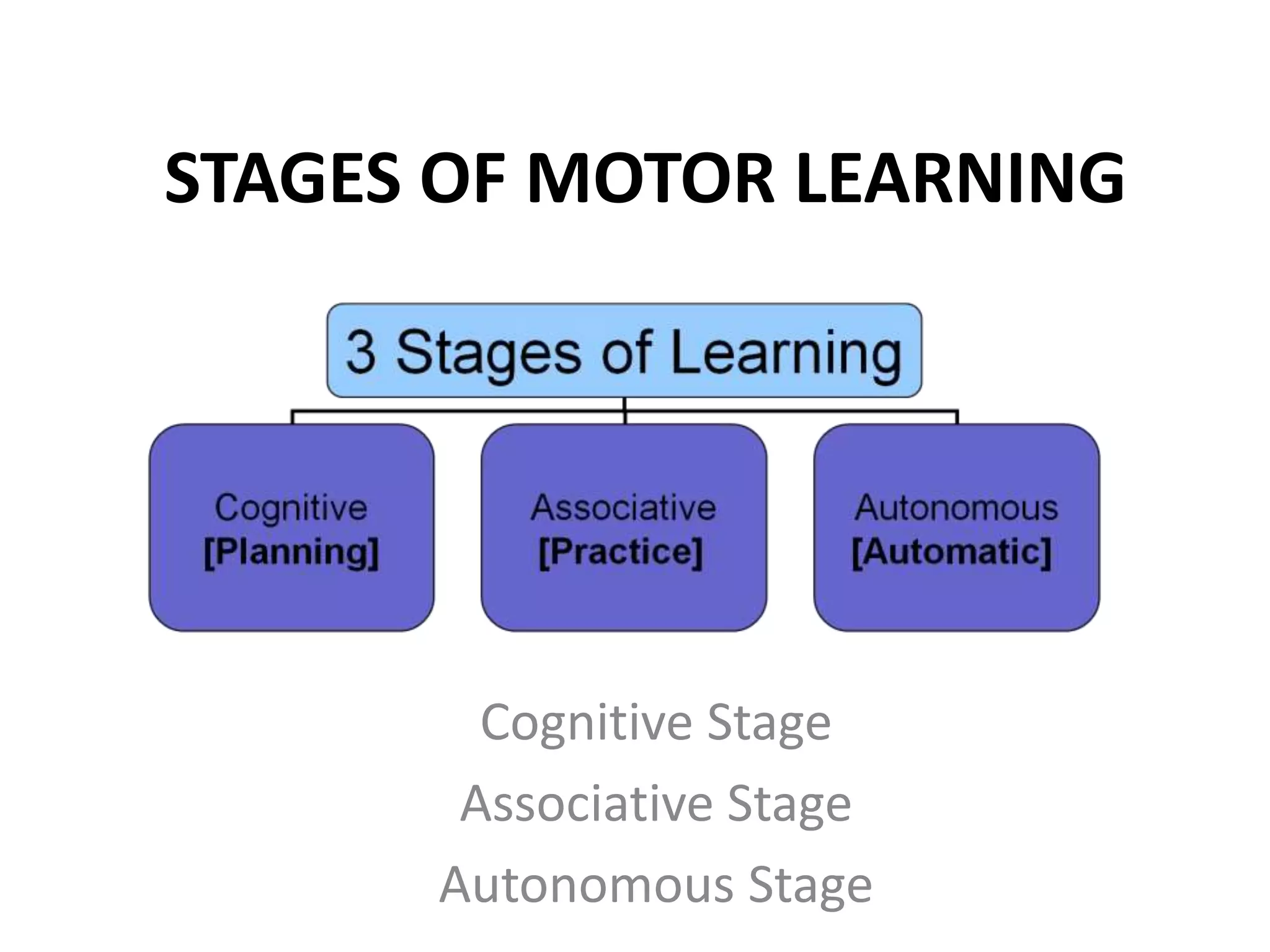

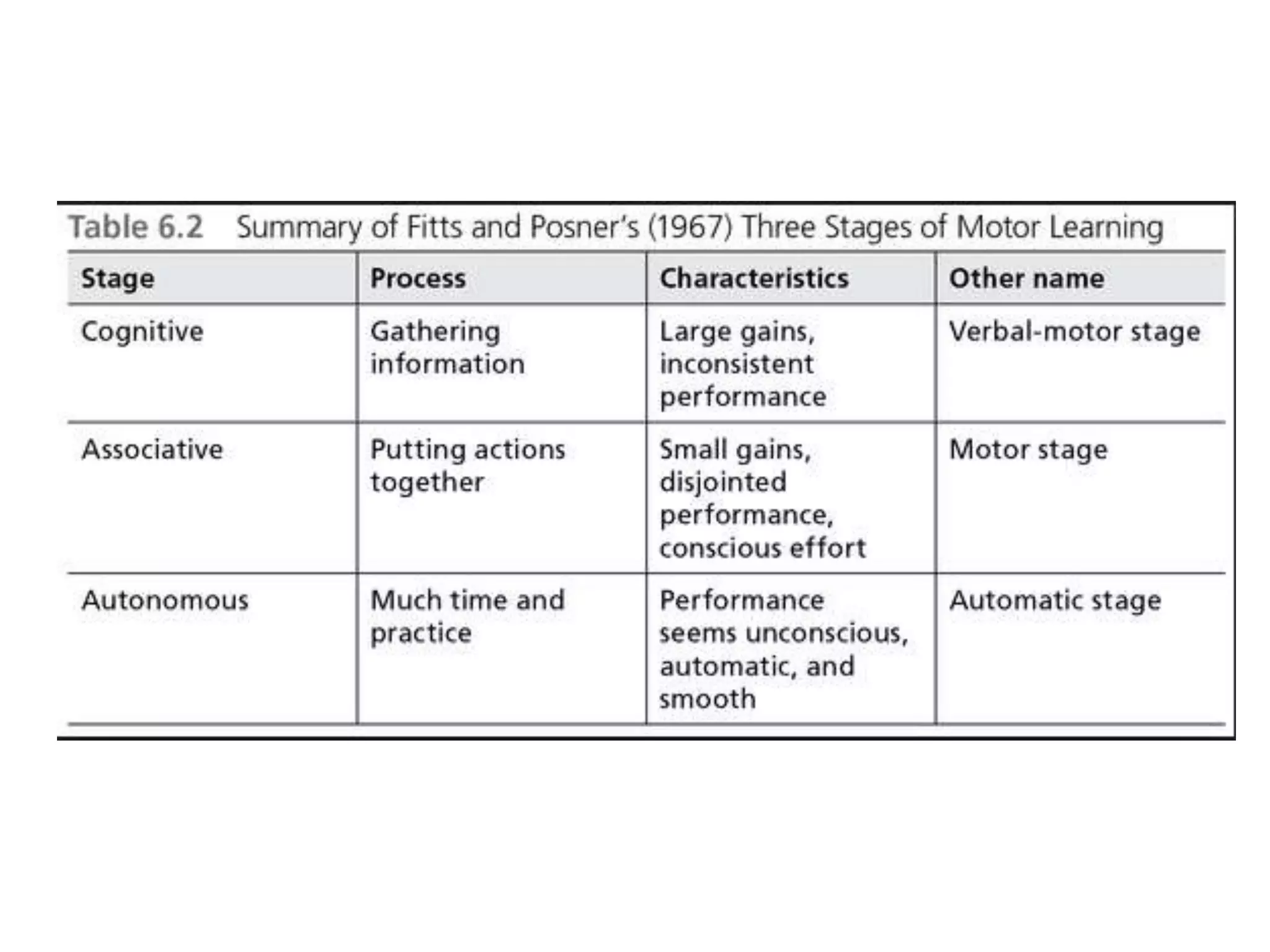

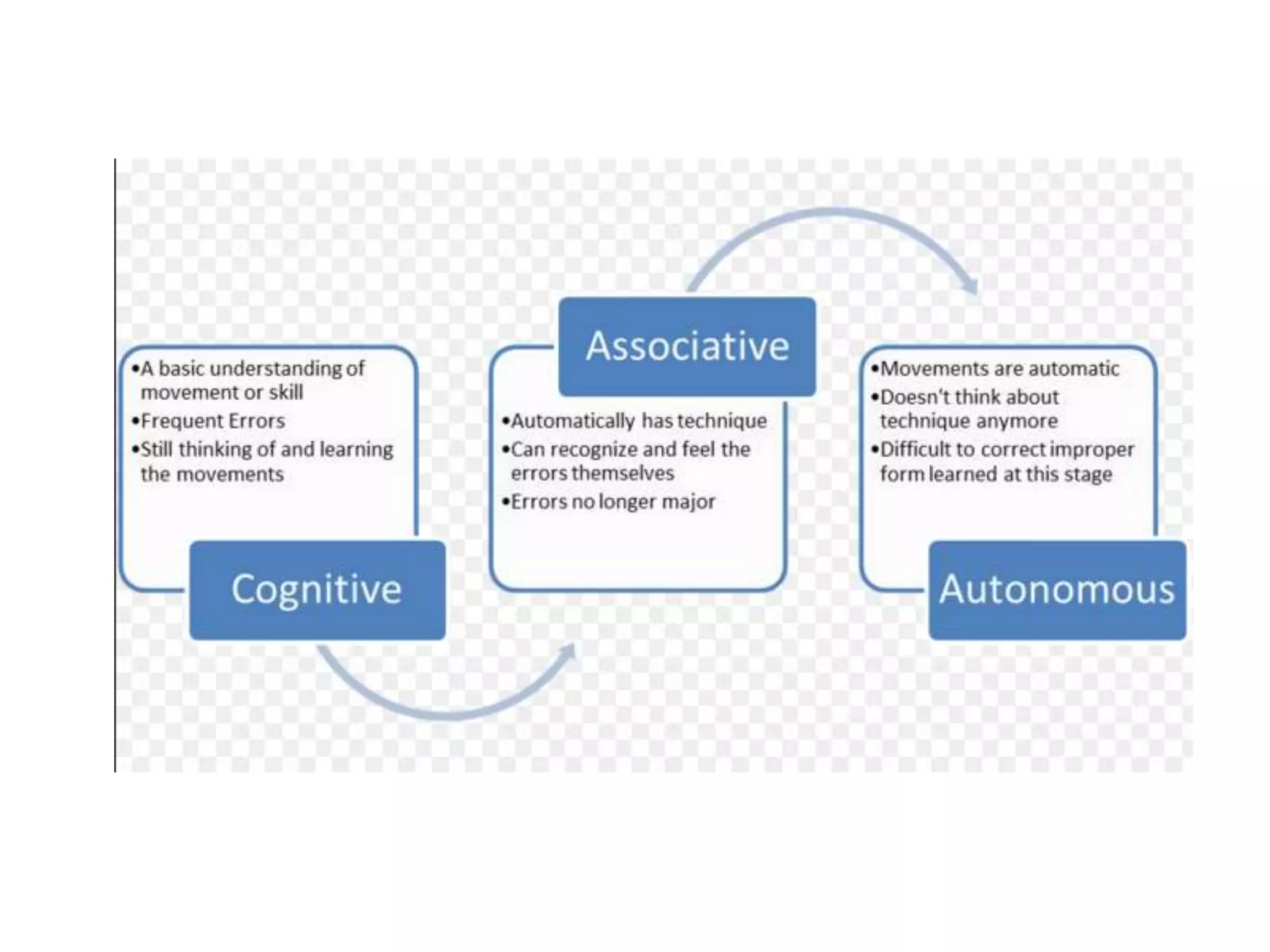

Motor learning involves acquiring and retaining skilled movements through practice. It modifies how sensory information is processed and motor actions are produced. There are three types of motor tasks: discrete tasks with clear beginnings and ends; serial tasks involving sequences of discrete movements; and continuous repetitive tasks without clear starts or stops. Motor learning progresses through cognitive, associative, and autonomous stages. The cognitive stage involves learning what and how to do a task through conscious effort. In the associative stage, movements are fine-tuned and errors decrease through practice. The autonomous stage is when movements become automatic without conscious effort.