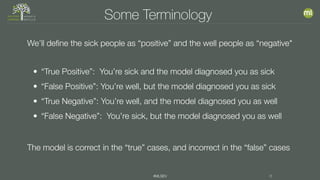

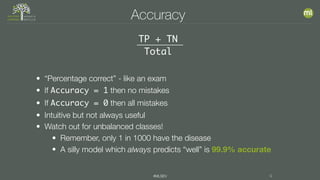

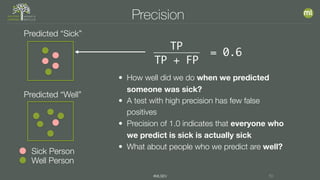

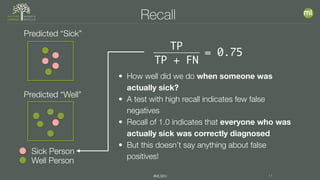

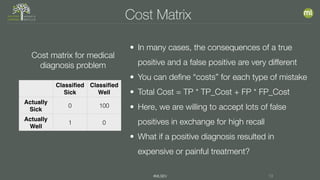

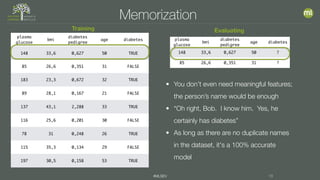

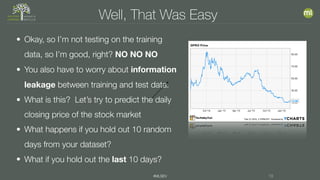

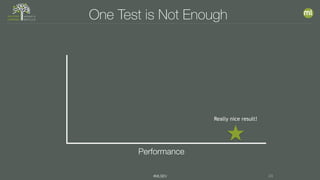

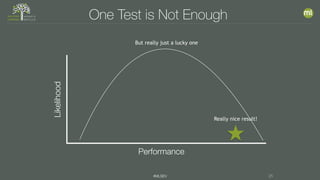

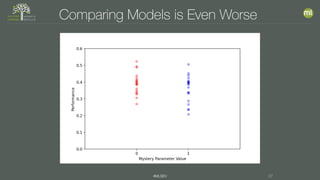

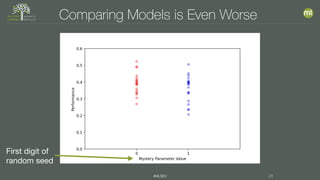

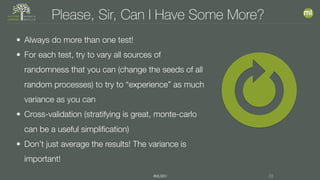

The document discusses the importance of proper model evaluation in machine learning, emphasizing the necessity of using appropriate metrics and ensuring that the testing data is distinct from training data to avoid information leakage. It elaborates on concepts such as accuracy, precision, recall, and trade-offs between these metrics, stressing the significance of holding out data for realistic testing. Additionally, it highlights the need for multiple tests to account for randomness in data and model performance to ensure reliability and validity in results.