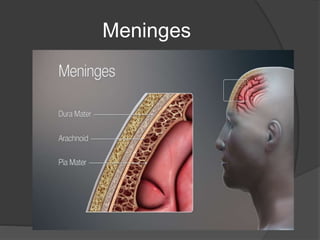

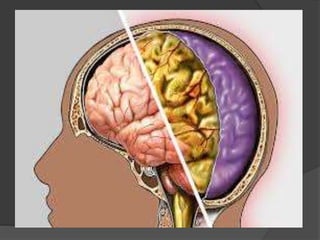

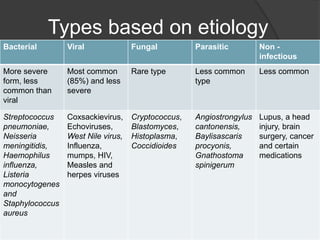

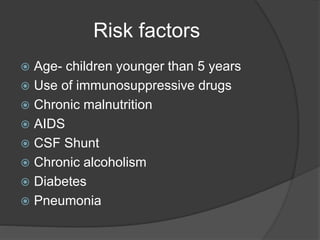

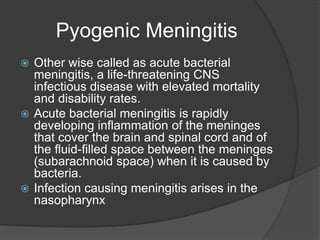

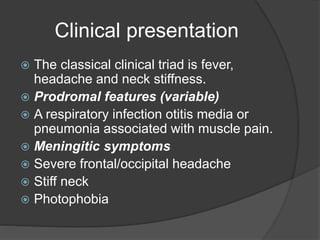

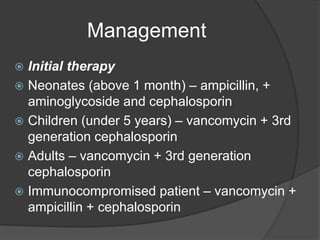

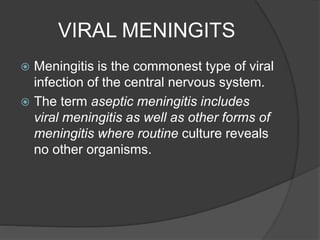

Meningitis is a serious public health issue caused by various pathogens, with bacterial meningitis having the highest impact, particularly in children under five. It is characterized by inflammation of the protective layers around the brain and spinal cord, leading to severe complications and high mortality rates, especially in less developed countries. Treatment involves antibiotics and supportive care, with vaccines available for prevention against specific types of meningitis.