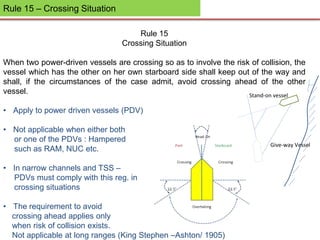

This document outlines the international regulations for preventing collisions at sea, highlighting key rules such as the overtaking rule (Rule 13), head-on situation (Rule 14), and actions by vessels in various scenarios. It details responsibilities for vessels in terms of right-of-way and necessary actions they must take to avoid collisions. Included are interpretations from court cases that illustrate how these rules have been applied in maritime law.

![Rule 15 & 17

(c) The power-driven vessel which takes action in a crossing situation in accordance

with sub paragraph (a)(ii) to avoid collision with another power-driven vessel

shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, not alter course to port for a vessel

on her port side.

(d) This rule does not relieve the give-way vessel of her obligation to keep out of the

way.

• Avoid turning to port to avoid collision

with another power driven vessel

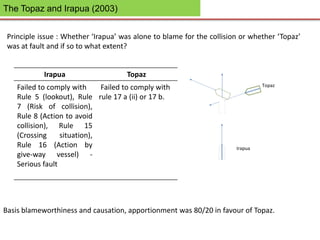

• The Topaz and Irapua [2003] EWHC

320:

Irapua (Give-way)

(From Necochea to Fortaleza)

Topaz (Stand-on)

(From Mohammedia to Ponta Ubu)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maritimelawfinalpresenationrevised1-130929195733-phpapp02/85/Maritime-law-presenation-15-320.jpg)

![Bibliography

• Howard Bennett, Maritime Law, Course Notes 2013.

• Simon Gault, Steven J. Hazelwood, 2003. Marsden on Collisions at Sea.

13th ed. London: Sweet and Maxwell

• A N Cockroft, J N F Lameijer, 2012. A guide to the collision

avoidance rules. 7th ed. London: Butterworth-Heinemann

• IMO 2003. COLREGS. 4th ed: IMO Publication

• The Topaz and Irapua (2003) EWHC 320

• The Ore Chief Lloyd's Law Reports, [1974] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 427

• Haugland v Karamea Lloyd's Law Reports , (1921) 9 Ll.L.Rep. 375

• The Angelic Spirit [ 1994] 2 LI LR 595

• The Maloja II (1993) 1 Lloyd’s Rep 48

• The 'British Engineer", Lloyd's Law Reports, (1944) 78 LL.L.Rep. 31

• Billings Victory (1949) 82 LI.L. Rep. 877

• Baines Hawkins (Moliere) 1893 7 Asp. 364 69

Thank you](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maritimelawfinalpresenationrevised1-130929195733-phpapp02/85/Maritime-law-presenation-18-320.jpg)