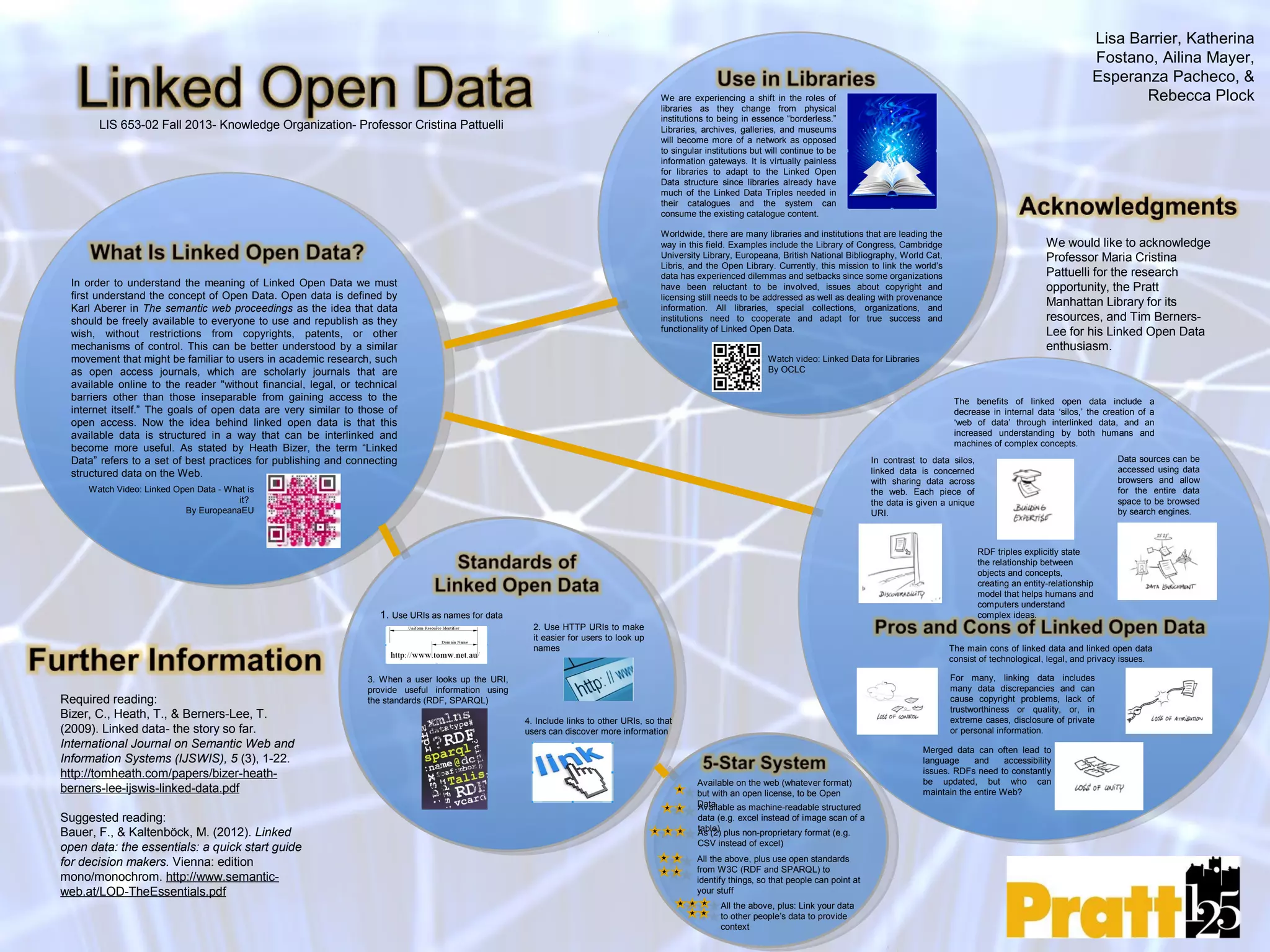

Libraries are shifting from physical institutions to becoming more "borderless" networks as they adapt to linked open data structures. As libraries share data across the web through unique URIs and RDF triples, it creates a "web of data" that helps both humans and machines understand complex concepts. However, linked open data also faces challenges related to data discrepancies, copyright and privacy issues. All libraries and cultural heritage institutions will need to cooperate and adapt their data practices to fully realize the benefits of linked open data.

![LIS 653-02 Knowledge Organization

Claire Dunning

Katherine Hessler

Rachel Smiley

Freya Yost

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr.

Cristina Pattuelli and Bree

Midavaine for their input and

assistance with this project.

REFERENCES

Baca, M. (12/9/2009). Controlled Vocabularies for Art, Architecture, and Material Culture. Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Third Edition. Doi: 10.1081/E-ELIS3-120044074

Bruns, A. (2008). Folksonomies: Produsage and/of knowledge structures. In Blogs, Wikipedia, second life, and beyond: From production to produsage (171-198). Peter Lang: New York.

Furner, J. (09 Dec 2009). Folksonomies. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1081/E-ELIS3-120043238#

Kroski, E. (2007). Folksonomies and user-based technology. In N. Courney (Ed.), Library 2.0 and beyond: Innovative technologies and tomorrow’s user (91-104). Libraries Unlimited: Westport, CT.

Levy, P. (2013). The creative conversation of collective intelligence. In A. Delwiche & J. J. Henderson (Eds.), The participatory cultures handbook (99-108). Routledge: New York.

McDaniel, C. (2012, October 11). Ontology, Taxonomy and Folksonomy. Digital History Rice. Retrieved December 1, 2013, from http://digitalhistory.blogs.rice.edu/2012/10/11/ontology-taxonomy-and-folksonomy

Mathes, A. (n.d.). Folksonomies - Cooperative Classification and Communication Through Shared Metadata. Folksonomies - Cooperative Classification and Communication Through Shared Metadata. Retrieved December 1, 2013, from

http://www.adammathes.com/academic/computer-mediated-communication/folksonomies.html

Pirmann, C. (2012). Tags in the Catalogue: Insights From a Usability Study of LibraryThing for Libraries. Library Trends, 61(1), 234-247.

Porter, J. (2011). Folksonomies in the Library: their impact on user experience and their implications for the work of librarians. The Australian Library Journal, 60(3), 248-255.

Rolla, P. (2009). User Tags versus Subject Headings: Can User-Supplied Data Improve Subject Access to Library Collections? Library Resources and Technical Services, 53(3), 174-184.

Sanderson, B. & Rigby, M. (November 2013). We’ve Reddit, have you?: What librarians can learn from a site full of memes. College and Research Libraries News, 74 (10), 518-521. http://crln.acrl.org/content/74/10/518.full.pdf+html

Terdiman, D. (01 February 2005). Folksonomies tap people power. Wired, 13 (2). Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2005/02/66456?currentPage=all

Trant, J. & Wyman, B. (2006). Investigating social tagging and folksonomy in art museums with steve.museum [PDF]. Retrieved 11/10/13 from http://www.ra.ethz.ch/cdstore/www2006/www.rawsugar.com/www2006/4.pdf

Vander Wal, T. (2007, February 2). Folksonomy. Home. Retrieved December 1, 2013, from http://vanderwal.net/folksonomy.html](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lis653fall2013finalprojectposters-140204201606-phpapp01/85/LIS-653-fall-2013-final-project-posters-3-320.jpg)