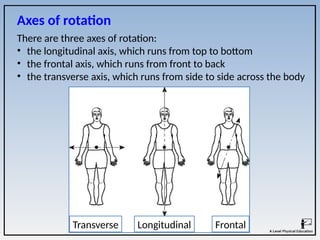

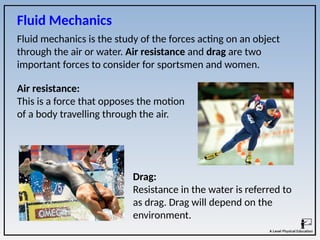

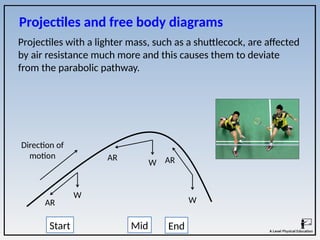

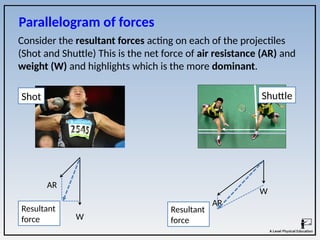

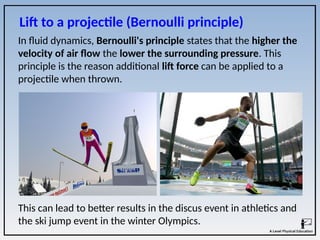

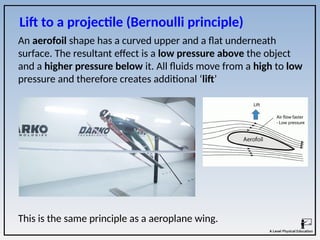

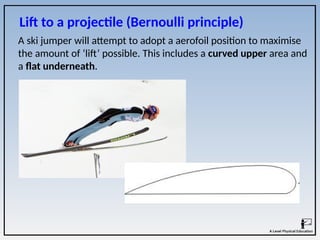

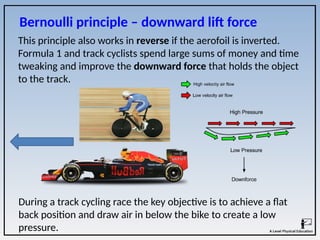

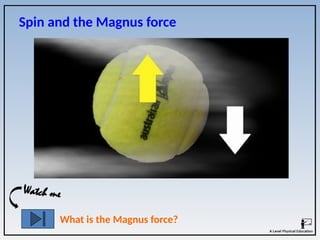

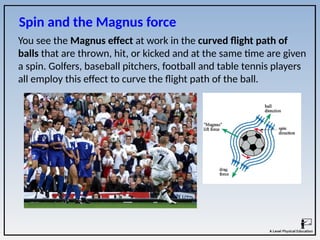

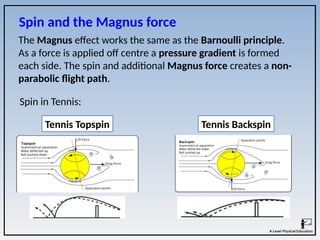

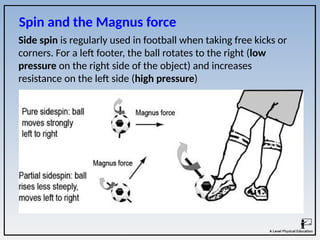

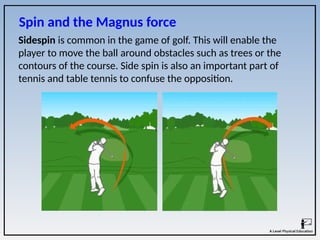

The document covers the principles of linear, angular, and projectile motion in human biomechanics, including key concepts such as distance, velocity, acceleration, moment of inertia, and angular momentum. It explains the factors affecting these motions, including air resistance, the Bernoulli principle, and the Magnus effect, along with their applications in sports. Additionally, it discusses the implications of Newton's laws of motion and provides examples of how these principles can be observed in athletic performance.

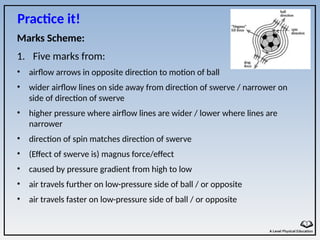

![Exam questions

1. A footballer taking a free kick may apply sidespin to the ball to

make it swerve. Draw and label an airflow diagram of the ball in

flight. Explain how spin causes the flight path of the ball to

deviate. [5]

Practice it!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linear-angular-projectile-motion1-240917110152-b32bdba0/85/Linear-angular-projectile-motion-1-pptx-65-320.jpg)

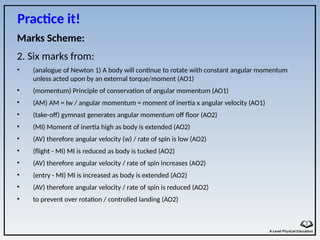

![Exam questions

2. Fig.3 shows a gymnast performing a back somersault. Explain

how angular velocity is controlled by the gymnast during take-off,

flight and landing. [6]

Practice it!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linear-angular-projectile-motion1-240917110152-b32bdba0/85/Linear-angular-projectile-motion-1-pptx-66-320.jpg)

![Exam questions

3. Identify two factors that affect the horizontal distance travelled

by a projectile. [2]

Practice it!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linear-angular-projectile-motion1-240917110152-b32bdba0/85/Linear-angular-projectile-motion-1-pptx-67-320.jpg)