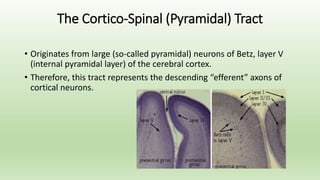

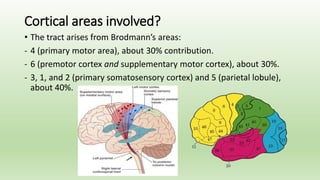

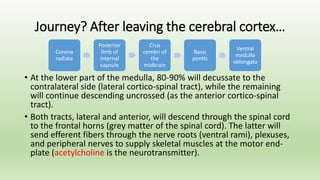

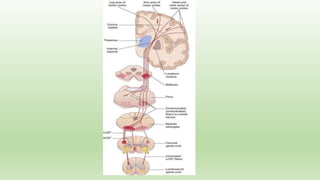

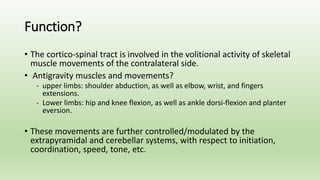

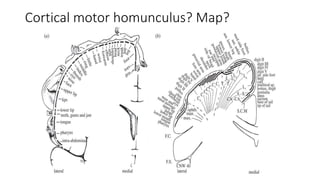

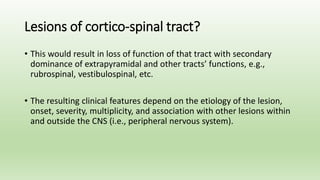

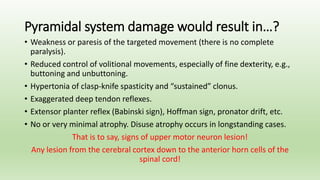

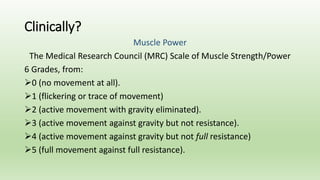

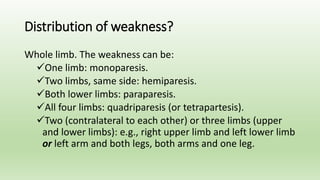

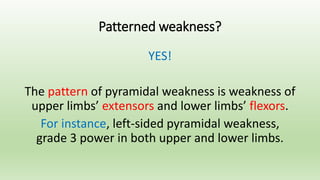

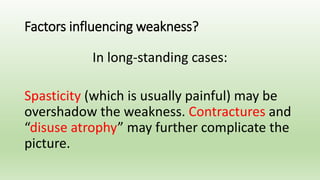

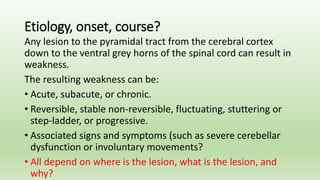

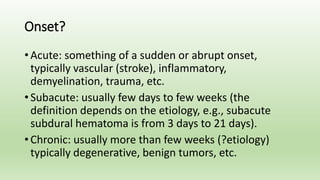

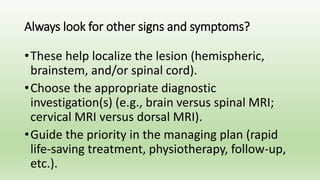

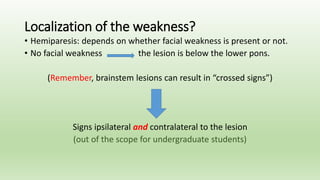

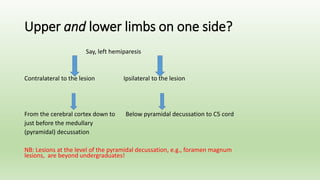

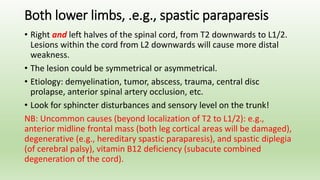

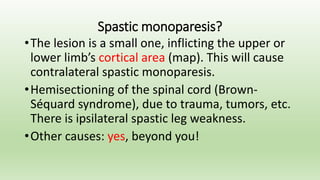

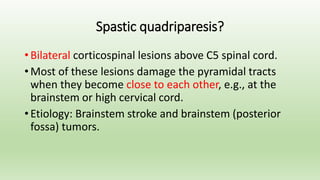

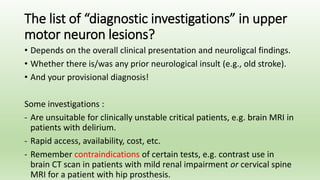

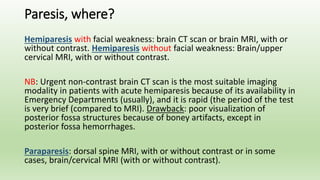

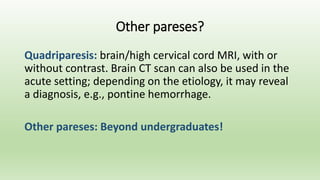

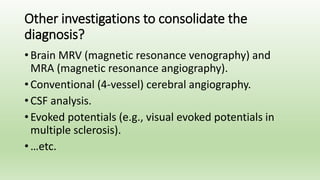

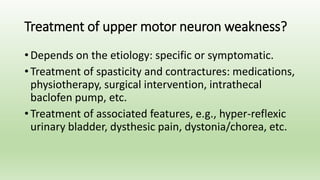

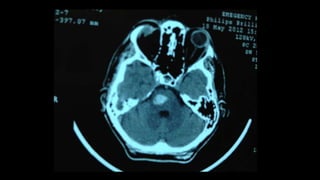

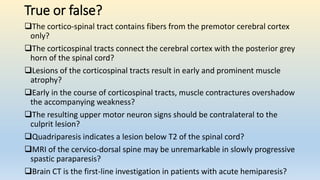

The document discusses upper motor neuron lesions, specifically focusing on the cortico-spinal tract's anatomy, function, and the resulting clinical features of lesions. It highlights how weaknesses in limb movements manifest and the various patterns of weakness based on the location of the lesions, along with diagnostic approaches and treatment options. Additionally, it covers the muscle strength grading scale and different types of paresis, as well as the significance of understanding lesion localization for effective diagnosis and management.