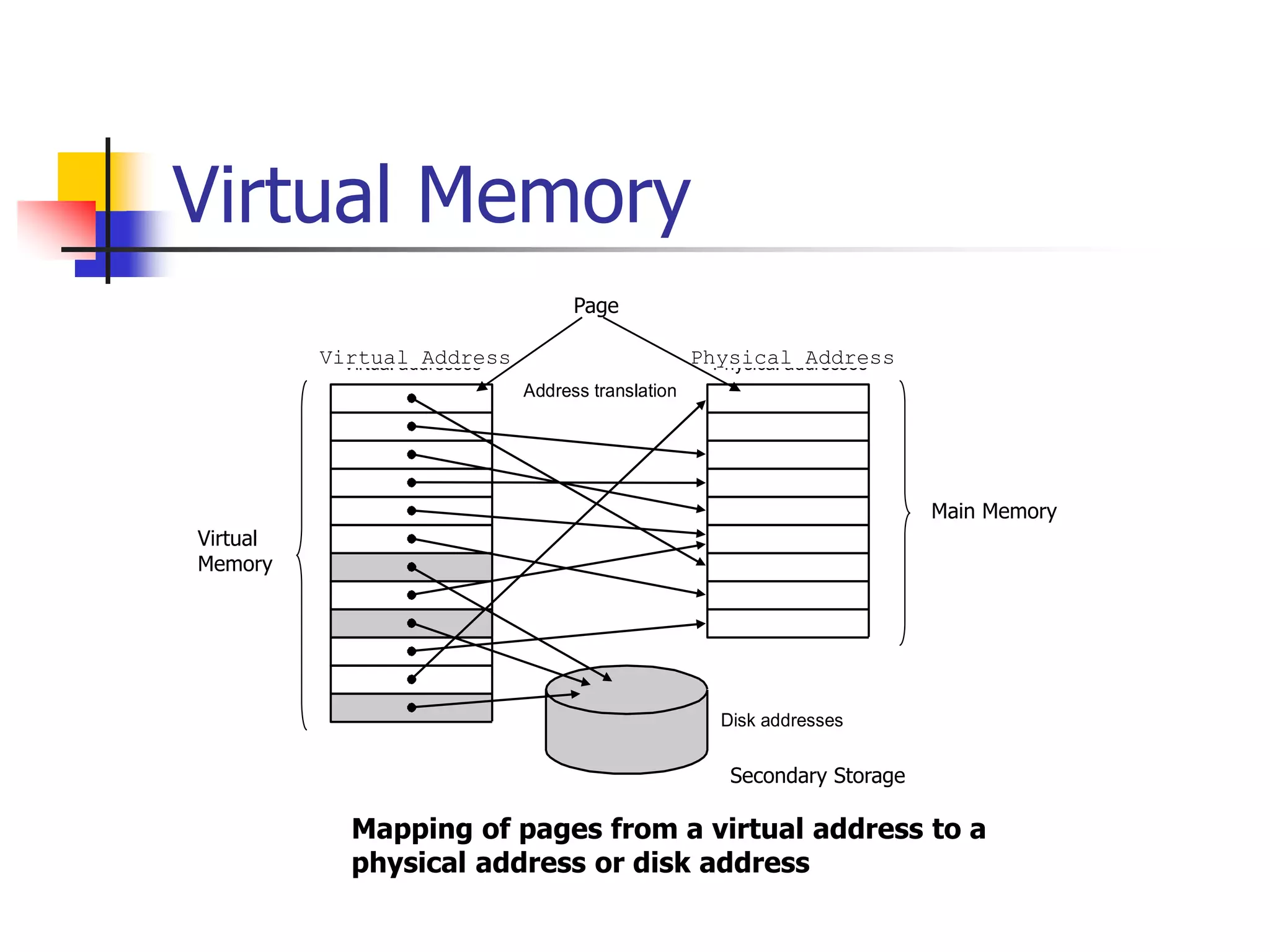

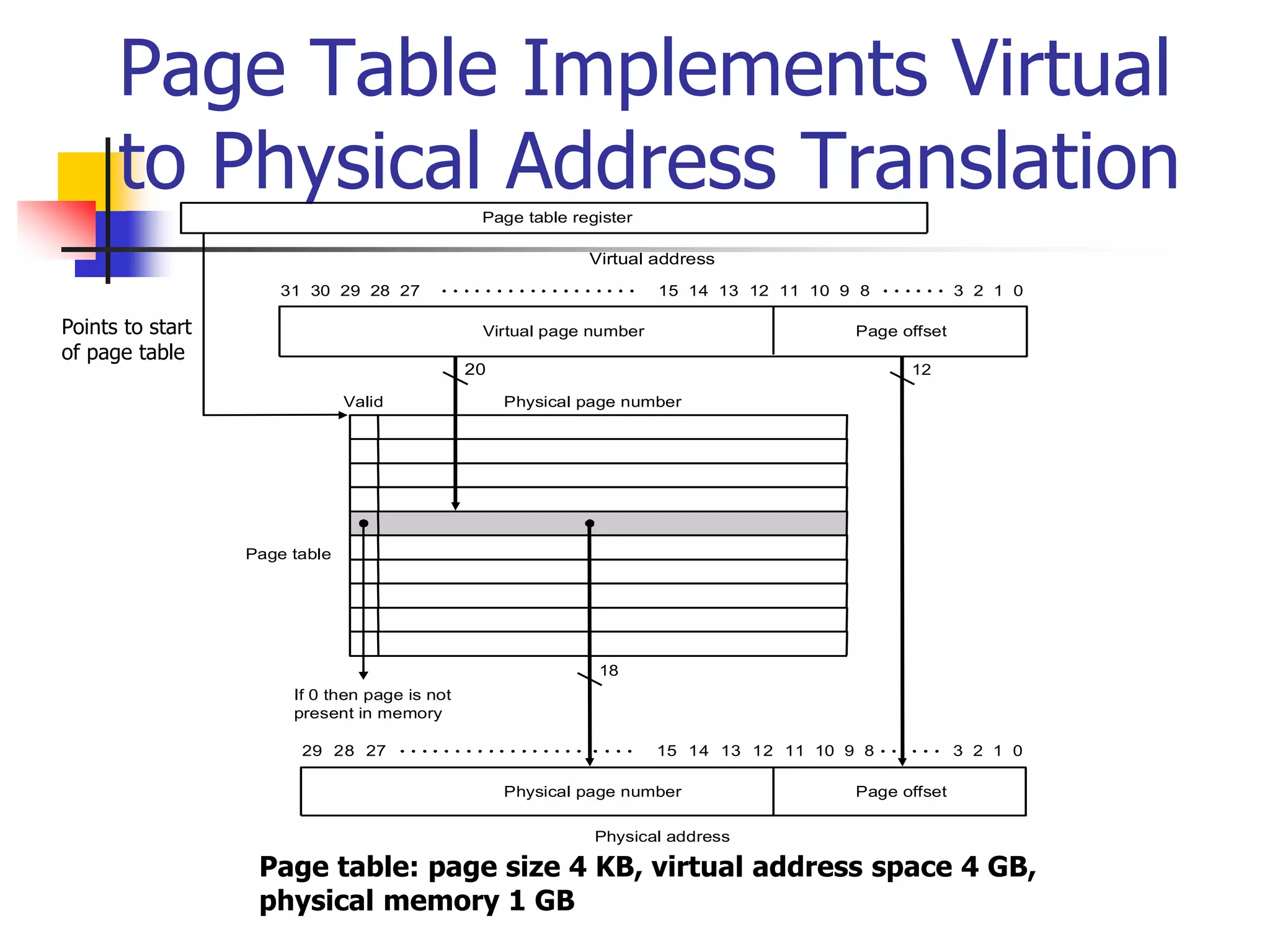

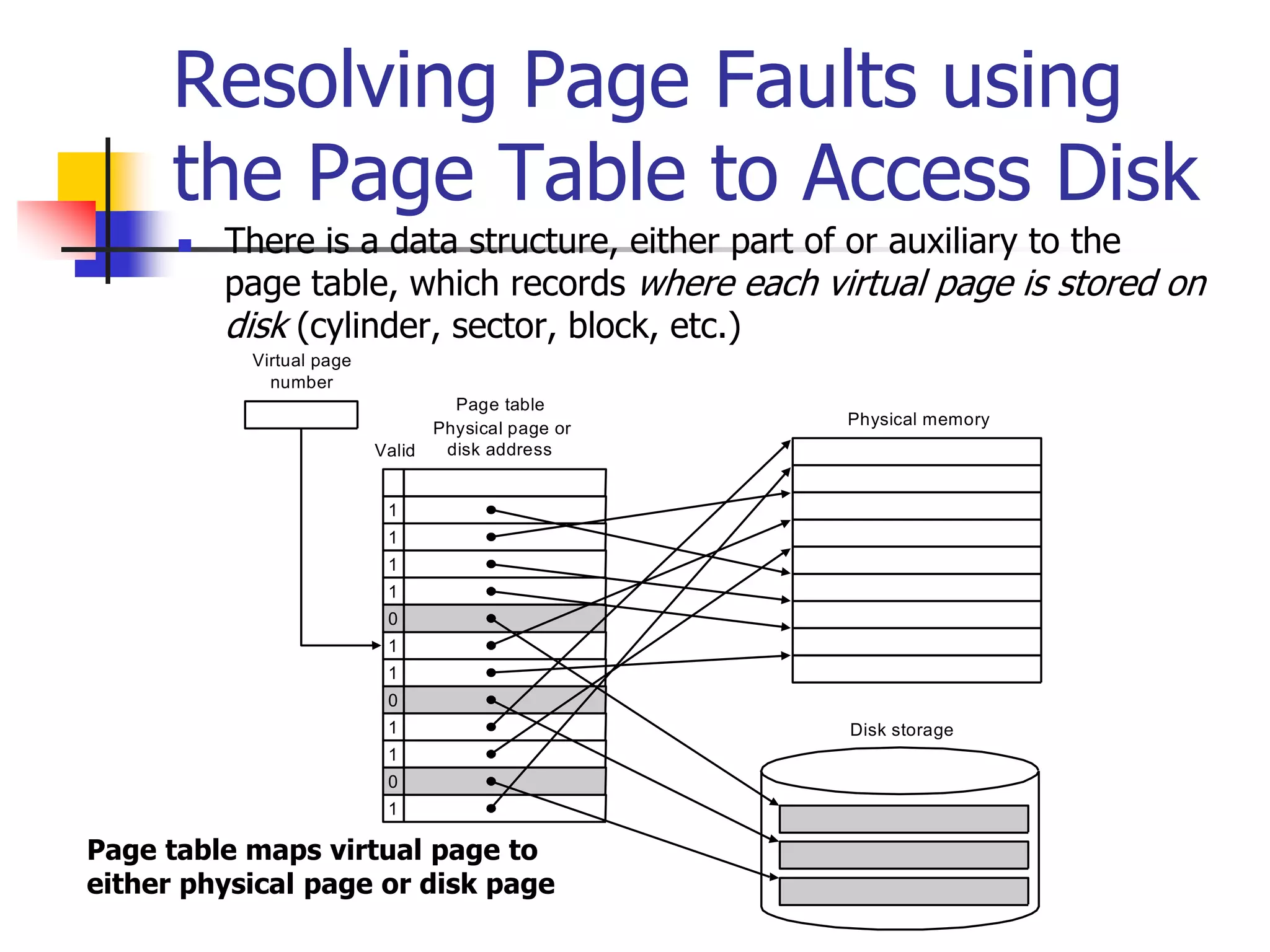

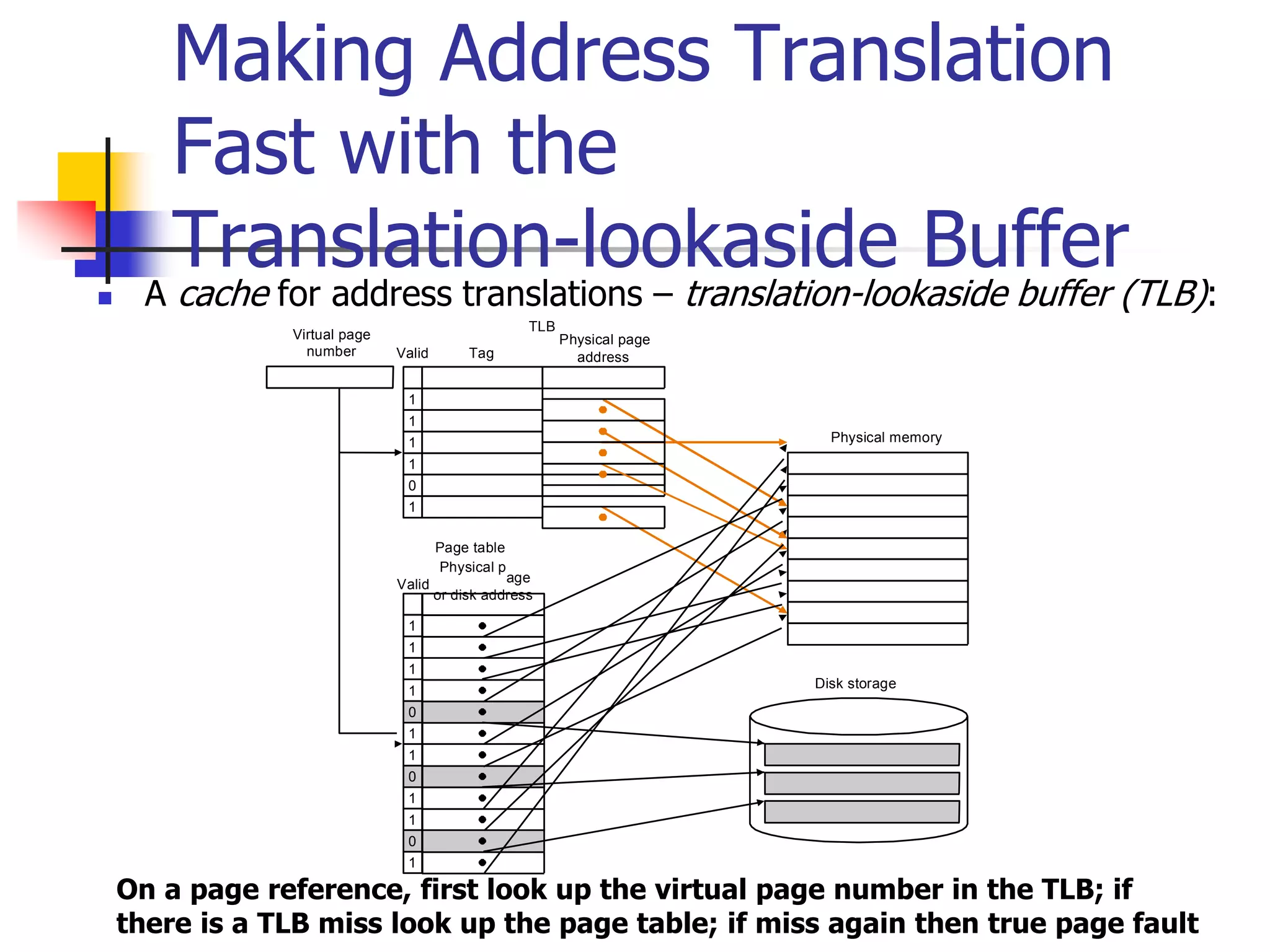

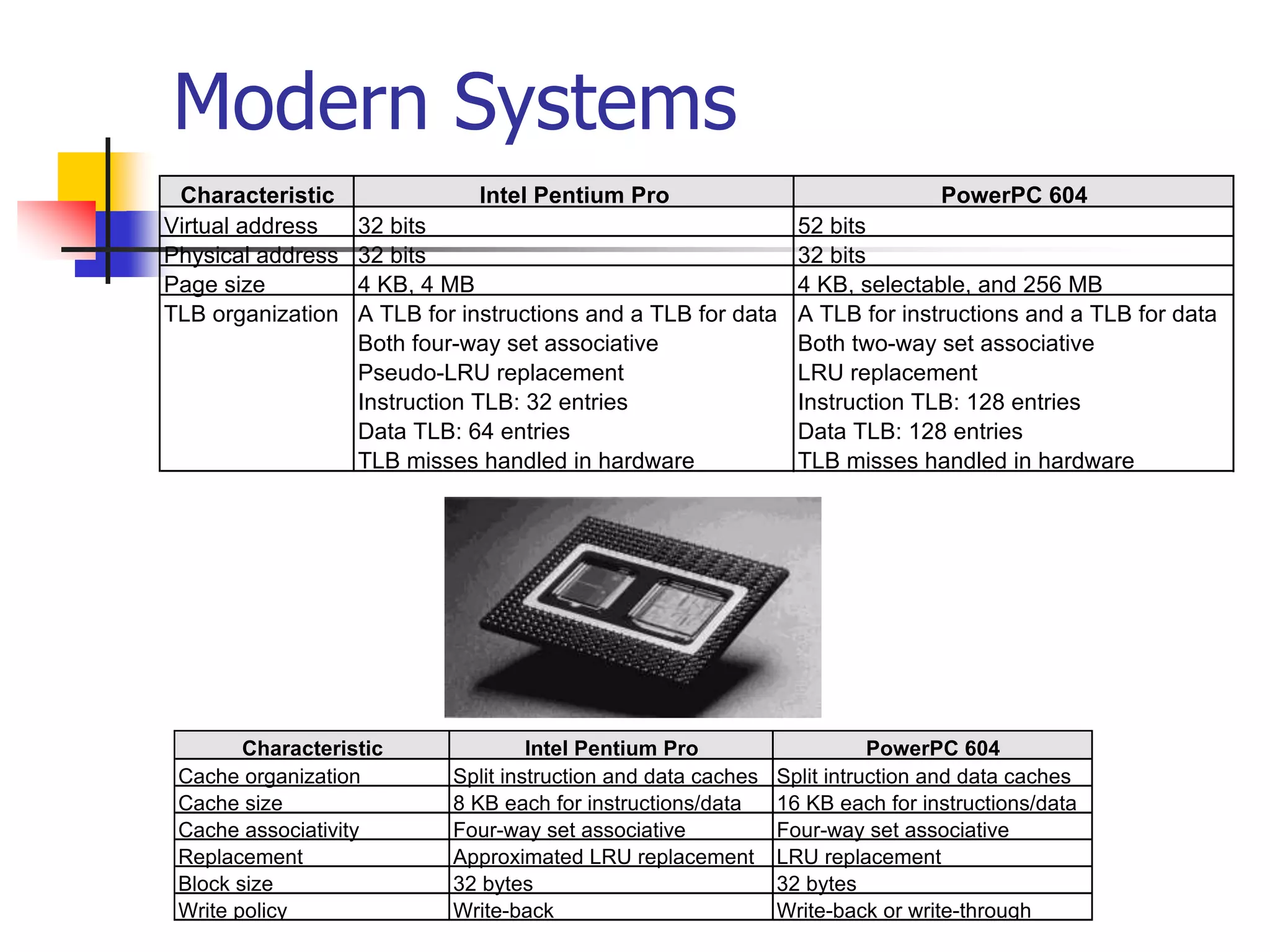

Virtual memory allows a program to access a larger virtual address space than physical memory by mapping virtual addresses to physical addresses or disk addresses. It uses a page table to translate virtual page numbers to physical page numbers in memory or disk addresses. When a page is accessed that is not in memory, a page fault occurs and the page is fetched from disk, which has a high latency. Modern systems use techniques like translation lookaside buffers and caching to speed up virtual memory translation.