The document provides an overview of modern petroleum refining processes, highlighting the evolution of the industry and the importance of technological advancements. It discusses various aspects of crude oil, including classifications based on location, density, and sulfur content, as well as characteristics like viscosity and pour point. Additionally, the document emphasizes the significance of petroleum in global energy consumption and its role in chemical production, underlining its critical importance to modern civilization.

+ as well as other oligomeric species. Furthermore, the solubility of

ferrous hydroxide and the composition of its soluble components depends on pH. In

general, solubility in the solvent phase can be given only for a specific solute which is

thermodynamically stable, and the value of the solubility will include all the species

in the solution (in the example above, all the iron-containing complexes).

Factors affecting solubility.

Solubility is defined for specific phases. For example, the solubility of aragonite and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-13-320.jpg)

![18

1.11.1 Types of aromatic compounds

The overwhelming majority of aromatic compounds are compounds of carbon, but

they need not be hydrocarbons.

a. Heterocyclics

In heterocyclic aromatics (heteroaromats), one or more of the atoms in the aromatic

ring is of an element other than carbon. This can lessen the ring's aromaticity, and thus

(as in the case of furan) increase its reactivity. Other examples include pyridine,

pyrazine, imidazole, pyrazole, oxazole, thiophene, and their benzannulated analogs

(benzimidazole, for example).

b. Polycyclics

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are molecules containing two or more simple

aromatic rings fused together by sharing two neighboring carbon atoms. Examples are

naphthalene, anthracene and phenanthrene.

Substituted aromatics Many chemical compounds are aromatic rings with other things

attached. Examples include trinitrotoluene (TNT), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin),

paracetamol, and the nucleotides of DNA.

c. Atypical aromatic compounds

Aromaticity is found in ions as well: the cyclopropenyl cation (2e system), the

cyclopentadienyl anion (6e system), the tropylium ion (6e) and the cyclooctatetraene

dianion (10e). Aromatic properties have been attributed to non-benzenoid compounds

such as tropone. Aromatic properties are tested to the limit in a class of compounds

called cyclophanes.

A special case of aromaticity is found in homoaromaticity where conjugation is

interrupted by a single sp³ hybridized carbon atom.

When carbon in benzene is replaced by other elements in borabenzene, silabenzene,

germanabenzene, stannabenzene, phosphorine or pyrylium salts the aromaticity is still

retained. Aromaticity also occurs in compounds that are not carbon-based at all.

Inorganic 6 membered ring compounds analogous to benzene have been synthesized.

Silicazine (Si6H6) and borazine (B3N3H6) are structurally analogous to benzene, with

the carbon atoms replaced by another element or elements. In borazine, the boron and

nitrogen atoms alternate around the ring.

Metal aromaticity is believed to exist in certain metal clusters of aluminium. Möbius

aromaticity occurs when a cyclic system of molecular orbitals, formed from pπ atomic

orbitals and populated in a closed shell by 4n (n is an integer) electrons, is given a

single half-twist to correspond to a Möbius strip. Because the twist can be left-handed

or right-handed, the resulting Möbius aromatics are dissymmetric or chiral. Up to now

there is no doubtless proof that a Möbius aromatic molecule was synthesized.

Aromatics with two half-twists corresponding to the paradromic topologies, first

suggested by Johann Listing, have been proposed by Rzepa in 2005. In carbo-benzene

the ring bonds are extended with alkyne and allene groups [1]

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-18-320.jpg)

![21

aroma. Some are carcinogenic.

These different molecules are separated by fractional distillation at an oil refinery to

produce gasoline, jet fuel, kerosene, and other hydrocarbons. For example, 2,2,4-

trimethylpentane (isooctane), widely used in gasoline, has a chemical formula of

C8H18 and it reacts with oxygen exothermically:

a. The number of various molecules in an oil sample can be determined in

laboratory. The molecules are typically extracted in a solvent, then separated

in a gas chromatograph, and finally determined with a suitable detector, such

as a flame ionization detector or a mass spectrometer.

b. Incomplete combustion of petroleum or gasoline results in production of toxic

byproducts. Too little oxygen results in carbon monoxide. Due to the high

temperatures and high pressures involved, exhaust gases from gasoline

combustion in car engines usually include nitrogen oxides which are

responsible for creation of photochemical smog.

1.13 Heat of combustion

At a constant volume the heat of combustion of a petroleum product can be

approximated as follows:

Qv = 12,400 − 2,100g2

………………………….(4)

where [Qv] is measured in cal/gram and [g] is the specific gravity at 60°F.

1.13.1 Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of petroleum-based liquids can be modeled as follows:

where K is measured in BTU. hr-1

ft-2

, t is measured in °F and g is the specific gravity

at 60°F.

1.13.2 Spreading

Oil that spreads and moves, when lighter than water, forming slicks that spread on the

surface, on streams, rivers and ponds in percentages that are influenced by gravity,

surface tension, viscosity, point of fluidity, winds and currents.

The temperature is another crucial variable to control spreading due to the

dependency that viscosity has on temperature. One should note that crude oils vary

widely in composition and their behavior on the ocean also varies. Even viscous crude

oils can spread quickly in thin layers. The action of the currents and wind spreads and

breaks the slicks into mobile portions of oil that will have the largest amounts (thicker)

near their leading edges.

Both wind and current affect the movement of the portions in the water. The effect of

the currents is 100% in rivers, while that of the wind is around 3% of the wind speed.

The effect of the wind is little felt in rivers, contrary to what happens in a pond where

the wind is the predominant element in oil displacement.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-21-320.jpg)

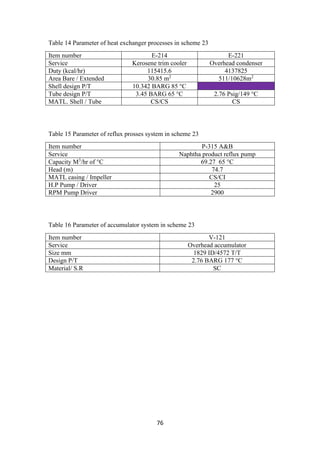

![26

upstream the emulsifying devices to improve the contact between the salt in the crude

oil and the wash water injected in the line.

The oil/water mixture is homogenously emulsified in the emulsifying device. The

emulsifying device (as a valve) is used to emulsify the dilution water injected

upstream in the oil. The emulsification is important for contact between the salty

production water contained in the oil and the wash water. Then the emulsion enters

the Desalters where it separates into two phases by electrostatic coalescence.

The electrostatic coalescence is induced by the polarization effect resulting from an

external electric source. Polarization of water droplets pulls them out from oil-water

emulsion phase. Salt being dissolved in these water droplets, is also separated along

the way. The produced water is discharged to the water treatment system (effluent

water). It can also be used as wash water for mud washing process during operation.

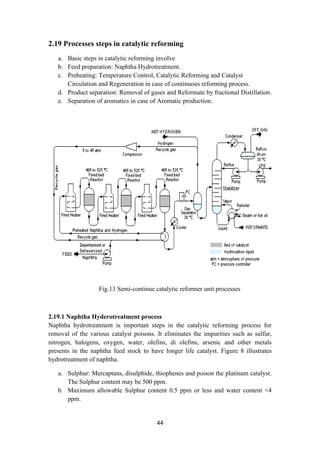

2.4 Crude distillation unit

The unit comprising of an atmospheric distillation column, side strippers, heat

exchanger network, feed de-salter and furnace as main process technologies enables

the separation of the crude into its various products. Usually, five products are

generated from the CDU namely gas + naphtha, kerosene, light gas oil, heavy gas oil

and atmospheric residue (figure 3). In some refinery configurations, terminologies

such as gasoline, jet fuel and diesel are used to represent the CDU products which are

usually fractions emanating as portions of naphtha, kerosene and gas oil. Amongst the

crude distillation products, naphtha, kerosene has higher product values than gas oil

and residue. On the other hand, modern refineries tend to produce lighter components

from the heavy products. Therefore, reactive transformations (chemical processes) are

inevitable to convert the heavy intermediate refinery streams into lighter streams.

Operating Conditions: The temperature at the entrance of the furnace where the crude

enters is 200 – 280°C. It is then further heated to about 330 – 370°C inside the

furnace. The pressure maintained is about 1 bar gauge [2]

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-26-320.jpg)

![31

the reflux drum. Some of this liquid is recycled back to the top of the column and this

is called the reflux.

Reflux refers to the portion of the overhead liquid product from a distillation column

or fractionator that is returned to the upper part of the column as shown in the

schematic diagram of a typical industrial distillation column. Inside the column, the

down flowing reflux liquid provides cooling and condensation of the up flowing

vapors thereby increasing the efficiency of the distillation column.

The more reflux provided for a given number of theoretical plates, the better is the

column's separation of lower boiling materials from higher boiling materials.

Conversely, for a given desired separation, the more reflux is provided, the fewer

theoretical plates are required. The condensed liquid that is removed from the system

is known as the distillate or top product.

Thus, there are internal flows of vapors and liquid within the column as well as

external flows of feeds and product streams, into and out of the column.

2.7 Vacuum distillation unit (VDU)

2.7.1 Process overview

Refineries today are facing new challenges in order to meet the requirements with

respect to environment, health and safety of the plant personnel and the quality of the

finished products.

With increasing crude oil prices, refineries are processing heavier, lower quality

crudes that set new challenges to further develop the processes and maximize the

yield of valuable distillates in an energy efficient way. Plant run-time targets are

increasing which sets more challenges for equipment reliability and process control.

Hydrocarbons should not be heated to too high temperature due to cracking reactions

that take place above about 400 °C. Coke deposits on piping and equipment increase

maintenance costs and reduce process unit run-time. Therefore, crude distillation

bottom (residue) is further processed in a vacuum column to recover additional

distillates, light and heavy vacuum gasoil as feedstock to cracking units or lube-oil

processing [3]

.

2.7.2 Three types of vacuum towers are used

1. Dry (no steam).

2. Wet without stripping.

3. Wet with stripping.

Distillation is carried out with absolute pressures in the tower flash zone area of 25 to

40 mmHg. To improve vaporization, the effective pressure is lowered even further by

the addition of steam to the furnace inlet and at the bottom of the vacuum tower. The

amount of stripping steam used is a function of the boiling range of the feed and the

fraction vaporized as well as furnace outlet temperatures (380 – 420°C).) Vacuum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-31-320.jpg)

![34

this process, light ends from the reformer gas are stripped to enhance the purity of

hydrogen to about 92 % (figure 8). Conceptually, hydrotreating is regarded as a

combination of chemical and physical processes [4-6]

.

2.11 Operating conditions

The operating condition of a hydrotreater varies with the type of feed. For Naphtha

feed, the temperature may be kept at around 280-425°C and the pressure be

maintained at 200 – 800 psig.

Fig.8 Hydro-desulfurization unit process

S

2

H + H

-

R

2

SH + H

-

R

H2S + NaOH NaSH + H2O

2.11.1 Corrosion

The presence of mercaptan sulfur may cause corrosion in the fuel pipes and the engine

cylinder and produce sulfur dioxide during combustion. In the past, Merox (a catalytic

mercaptan oxidation method) treatment was done to convert corrosive mercaptans to

non-corrosive disulfide, but this did not remove the sulfur originally present in the

fuel. However, it did give rise to the formation of sulfur dioxide during combustion.

Since emission of sulfur dioxide is prohibited by environmental protection laws,

nowadays mercaptans and other sulfur compounds are mostly removed.

by a catalytic hydrodesulfurization unit in a refinery. The corrosive effects of other

organic compounds along with traces of sulfur-bearing compounds and additives must

be tested in the laboratory. The copper corrosion test similar to that described in the

testing of LPG is also carried out in the laboratory at standard temperature (50°C) for

3 h.

Catalyst

Heat](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-34-320.jpg)

![36

The Merox reactor is a vertical vessel containing a bed of charcoal that have been

impregnated with the cobalt – base catalyst. The charcoal may be impregnated with

the catalyst in situ, or they may be purchased from market as pre-impregnated with

the catalyst. An alkaline environment is provided by caustic being pumped into

reactor on an intermittent, as needed basis.

The jet fuel or kerosene feedstock from the top of the caustic prewash vessel is

injected with compressed air and enters the top of the Merox reactor vessel along with

any injected caustic. The mercaptan oxidation reaction takes place as the feedstock

percolates downward over the catalyst. The reactor effluent flows through a caustic

settler vessel where it forms a bottom layer of caustic solution and an upper layer of

water-insoluble sweetened product.

The caustic solution remains in the caustic settler so that the vessel contains a

reservoir for the supply of caustic that is intermittently pumped into the reactor to

maintain the alkaline environment.

The sweetened product from the caustic settler vessel flows through a water wash

vessel to remove any entrained caustic as well as any other unwanted water-soluble

substances, followed by flowing through a salt bed vessel to remove any entrained

water and finally through a clay filter vessel. The clay filter removes any oil-soluble

substances, organometallic compounds (especially copper) and particulate matter,

which might prevent meeting jet fuel product specifications.

The pressure maintained in the reactor is chosen so that the injected air will

completely dissolve in the feedstock at the operating temperature [7-10]

.

The overall oxidation reaction that takes place in converting mercaptans to disulfides

is:

O

2

→ 2RSSR + 2H

2

RSH + O

4

The most common mercaptans removed are:

]

mercaptan

-

SH [m

3

CH

-

Methanethiol

]

]

mercaptan

-

SH [e

5

H

2

C

-

Ethanethiol

]

]

P mercaptan

-

SH [n

7

H

3

C

-

Propanethiol

-

1

]

]

mercaptan

3

[2C

3

CH(SH)CH

3

CH

-

Propanethiol

-

2

]

[Butanethiol - C4H9SH [n-butyl mercaptan]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-36-320.jpg)

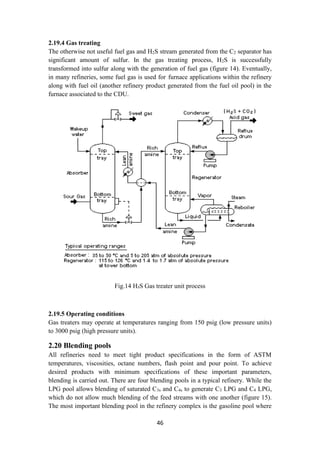

![47

in both premium and regular gasoline products are prepared by blending appropriate

amounts of n-butane, reformate, light naphtha, alkylate and light cracked naphtha as

shown in figure 15. These two products are by far the most profit-making products of

the modern refinery and henceforth emphasis is there to maximize their total products

while meeting the product specifications. The gasoil pool produces automotive diesel

and heating oil from kerosene (from CDU), LGO, LVGO and slurry [10]

. In the fuel oil

pool (figure 15), haring diesel, heavy fuel oil and bunker oil are produced from

LVGO, slurry and cracked residue.

Fig.15 Blending pools or Blending drum

2.21 Stream splitters

To facilitate stream splitting, various stream splitters are used in the refinery

configuration. A kerosene splitter is used to split kerosene between the kerosene

product and the stream that is sent to the gas oil pool as in figure 16. Similarly, butane

splitter splits the n-butane stream into butanes entering LPG pool, gasoline pool and

isomerization unit.

Unlike naphtha splitter, these two splitters facilitate stream distribution and do not

have any separation processes built within them. With these conceptual diagrams to

represent the refinery, the refinery block diagram with the complicated interaction of

streams is presented in figure 16.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-47-320.jpg)

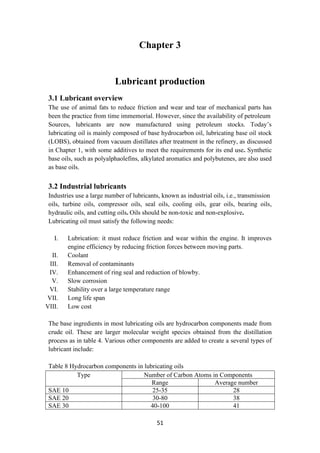

![58

which are suitable for use in high temperatures and the oxidizing environment of

engines. Load (weight to carry) and speed of the vehicles are also to be taken care of

before selecting a lube oil to apply. Usually, the temperature of an engine rises rapidly

during the startup and continues at that temperature during motion. Such a wide and

sudden change in temperature demands that the lubricant should have a high VI. In

addition to temperature fluctuations, lubricants are prone to oxidation and cracking,

leading to the formation of cokes, carbons, and gummy substances, which may

ultimately deposit on the engine, causing irreparable damage. In addition to engine

oils, different lubricants are applicable for other parts of the vehicle, such as the gears,

brake, clutch, and bearings. Gear boxes contain the gears immersed in lubricating oil

having low viscosity to reduce friction at high speed. The brake and clutch require

lubricating oils of low viscosity. Bearings are used in various parts of the automobile

from engine to wheels and require low to high viscous lubricants. At low temperatures

and high load, bearings at wheels are lubricated by grease. Since materials of

construction and type of engines vary with the make, appropriate lubricants are

selected and prescribed by the manufacturers. No single lubricant is therefore

applicable for all makes. Finished lubes are classified according to the Society of

Automotive Engineers’ (SAE). The viscosity of the lubricants and its variation with

temperature (VI) and the pour point are the important parameters to satisfy the

compatibility of application of lubes. Winter grades are classified as SAE numbers

from 0 to 25W as typical examples of cold temperatures and from 20 to 60 SAE

numbers for warming up the cranks of engines. A multigrade lubricant is a blend of

more than one type of lubricant. For example, SAE15W 50 is an example of a blend

of two grade oils. Usually, polymeric materials, such as ethylene propylene

copolymer, polymethyl acrylate, and butadiene, are added to these multigrade oils.

However, rigorous testing of appropriate lubes must be carried out on cars of different

makes in the testing laboratory or workshop for their suitability before prescribing

them for engines and other parts. Since the performance of these lubes may not be

satisfactory after a certain period of time due to degradation because of

contamination, reaction, physical and chemical changes in the property of the

ingredients or the base oils, it is inevitable that the lube must be drained out and

replaced with fresh stock. This drain out period must be specified for the prescribed

lubricants. The longer the drain out period, the more attractive the lubricant is in the

market [11][12]

.

3.6 Additives

Lubricants are comprised primarily of base oils and additives. Grease is comprised of

base oils and additives along with thickeners.

The following is a brief description of lubricant additives and their functions:

I. Anti-wear additive: Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZDDP) is the most

common antiwear additive, although there are many zinc-free additives based

on sulfur and phosphorus that also impart anti-wear properties. The zinc-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-58-320.jpg)

![65

b. Non-soap Base

Polyuria, Modified betonies and other clays like Colloidal, silica, Organic

compounds Fluorinated compounds

3.7.2 Grease additives

The additives used in greases are very similar to those used in lubricating oils, which

are listed below. Some additives that you would expect to find in grease include

Antioxidants or oxidation inhibitors.

a. Corrosion inhibitors

l. 30 Color stabilizers Dyes.

ll. Film strength agents metal deactivators rust inhibitors stringiness additive’s

structure modifiers for soap-oil systems.

3.7.3 Grease Fillers

In addition to soap, base oil and additives, solid fillers can be added to grease to

enhance its lubricity and load carrying ability. Some of the fillers used in lubricating

greases are listed below:

1. Graphite colloidal flake powdered.

2. Lead powder molybdenum disulfide.

3. Red lead powder.

4. Zinc oxide.

5. Copper flake.

6. Zinc dust.

3.8 Finished products

Using the above intermediates, a variety of plastics, rubber, fiber, solvent, paint, etc,.

are manufactured. Polymerisation reactions are carried out for these monomers or

intermediates to various polymers, resinous and liquid products. Plastics are available

in the form of extrudates, granules, powders, beads, etc., from the manufacturing units

as the finished products. These are converted into plastic commodities, such as bags,

films, furniture, and products of various shapes and sizes by casting, molding, or

blowing machines, as the marketable products. Plastics are classified ed into two

types, namely, thermoplastic (or thermoplast) and thermosetting plastics or

(thermoset). Thermoplasts, usually linear in molecular structure, can be melted (or

softened) by heating and solidify ed (or hardened) by cooling. This heating and

cooling cycle can be repeated indefinitely without loss of the original properties. But

thermosets will be permanently transformed to a chemically cross linked or non-linear

structure and cannot be returned to their original property during a heating and

cooling cycle [13]

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecturenotesinmodernpetroleumrefiningprocesses-230129175316-09122da0/85/Lecture-Notes-in-Modern-Petroleum-Refining-Processes-65-320.jpg)