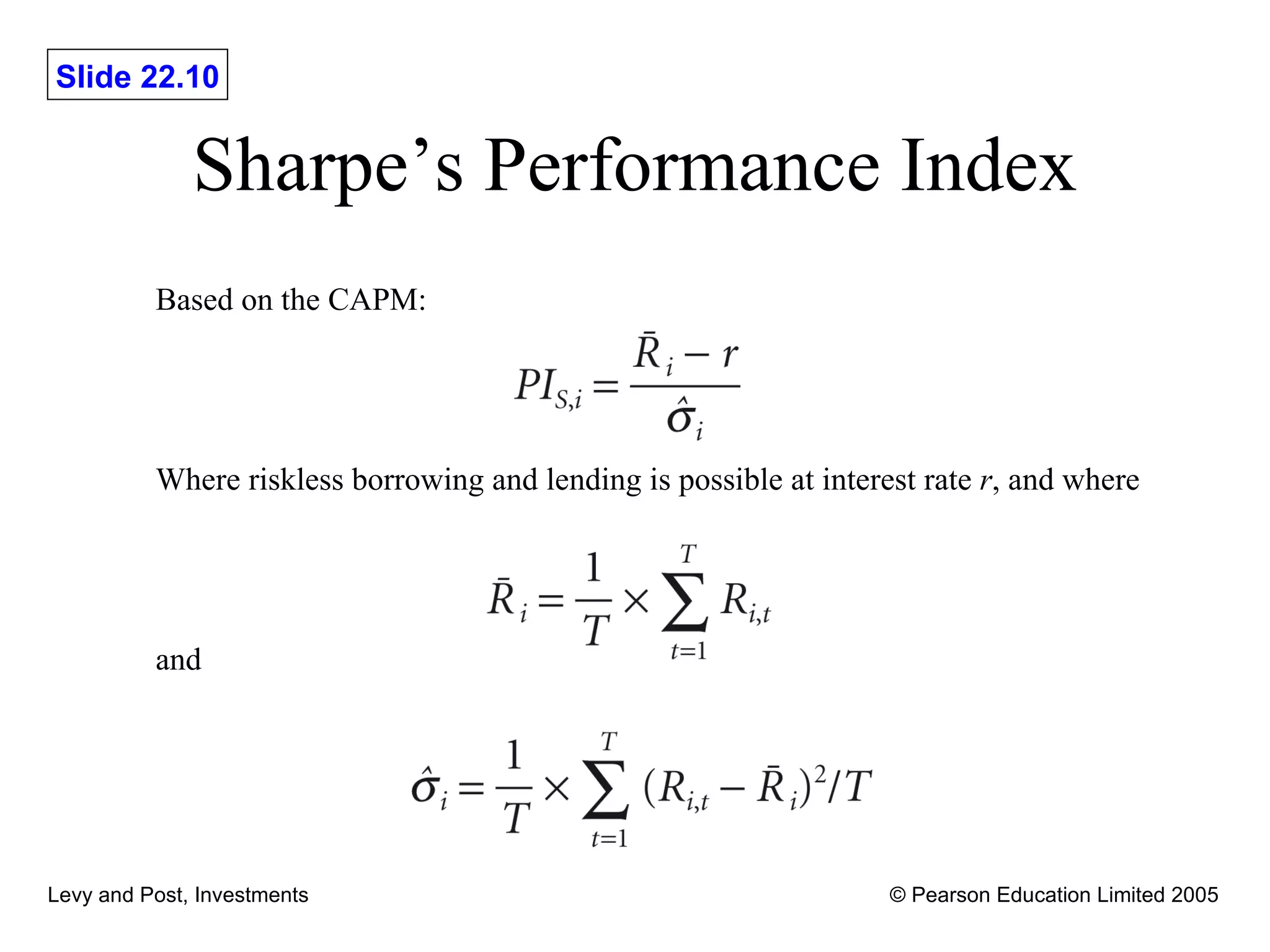

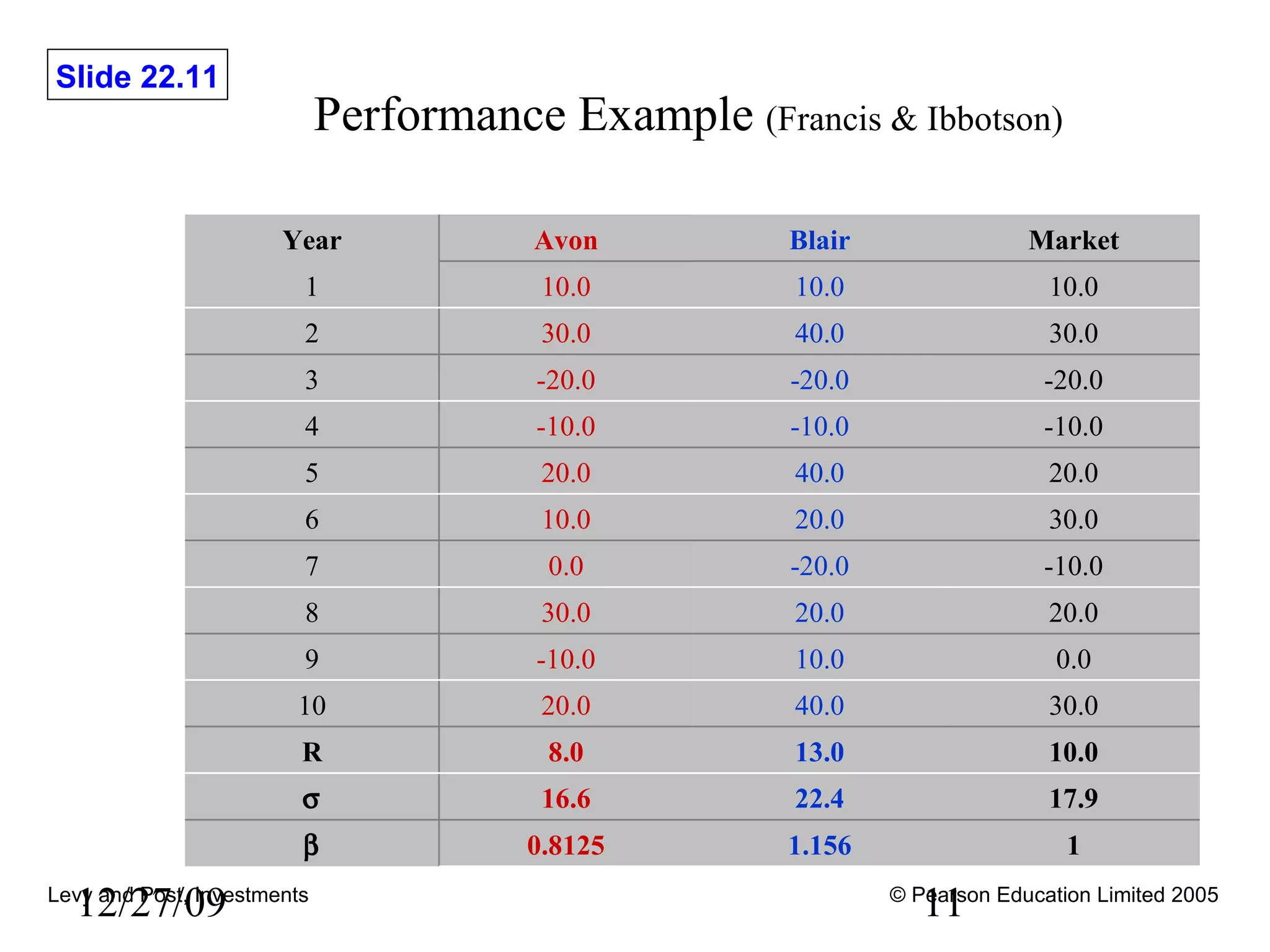

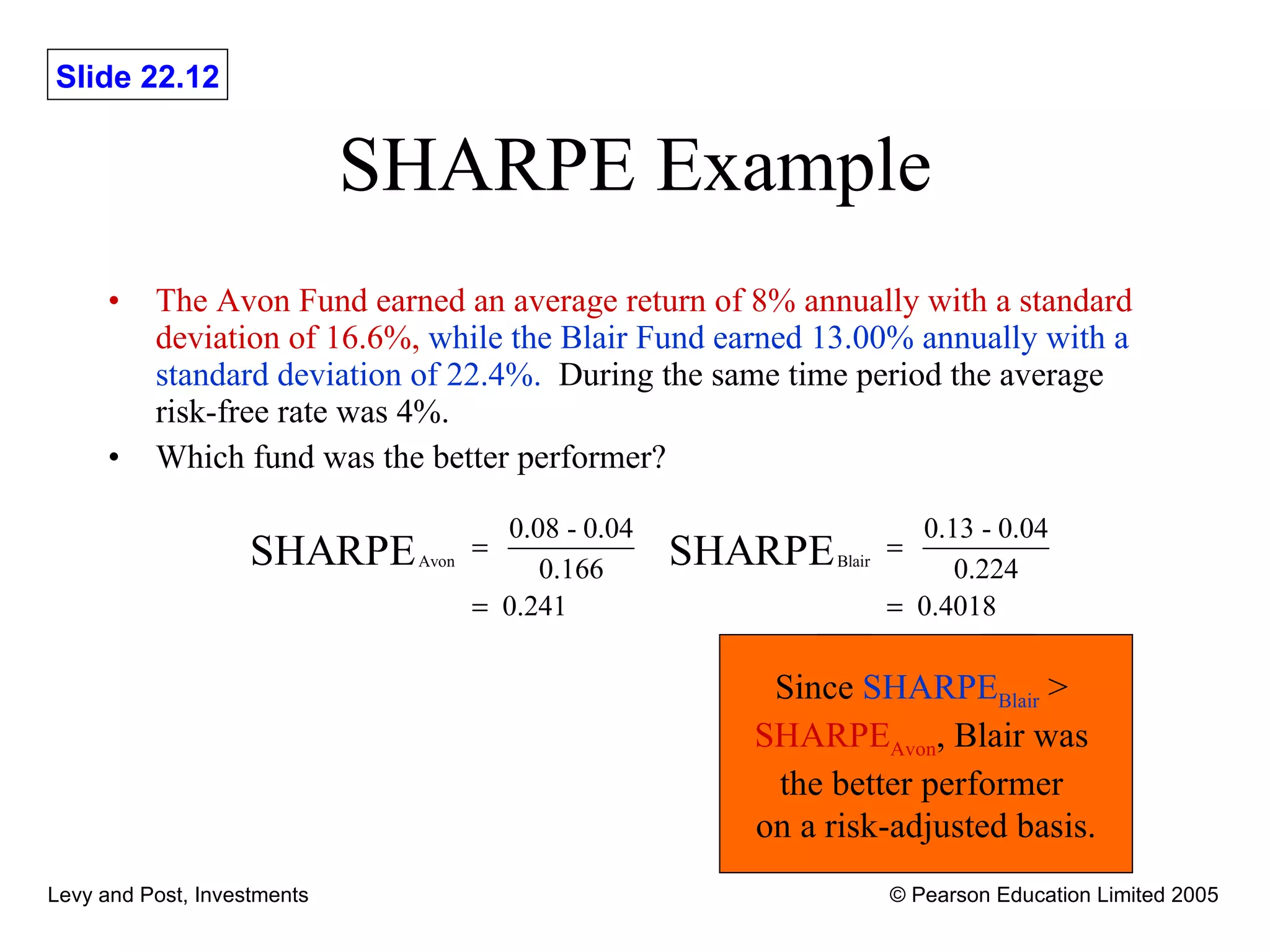

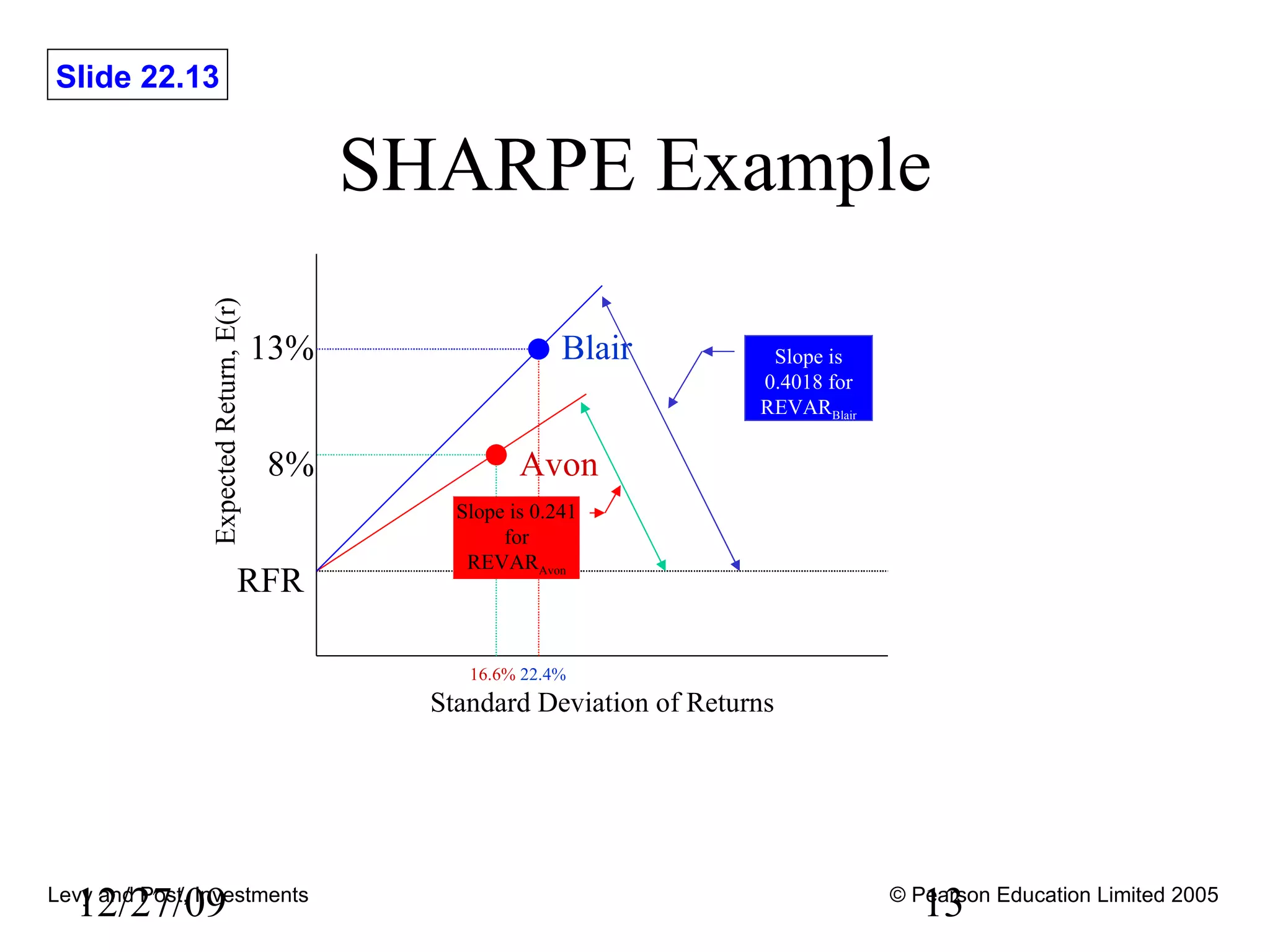

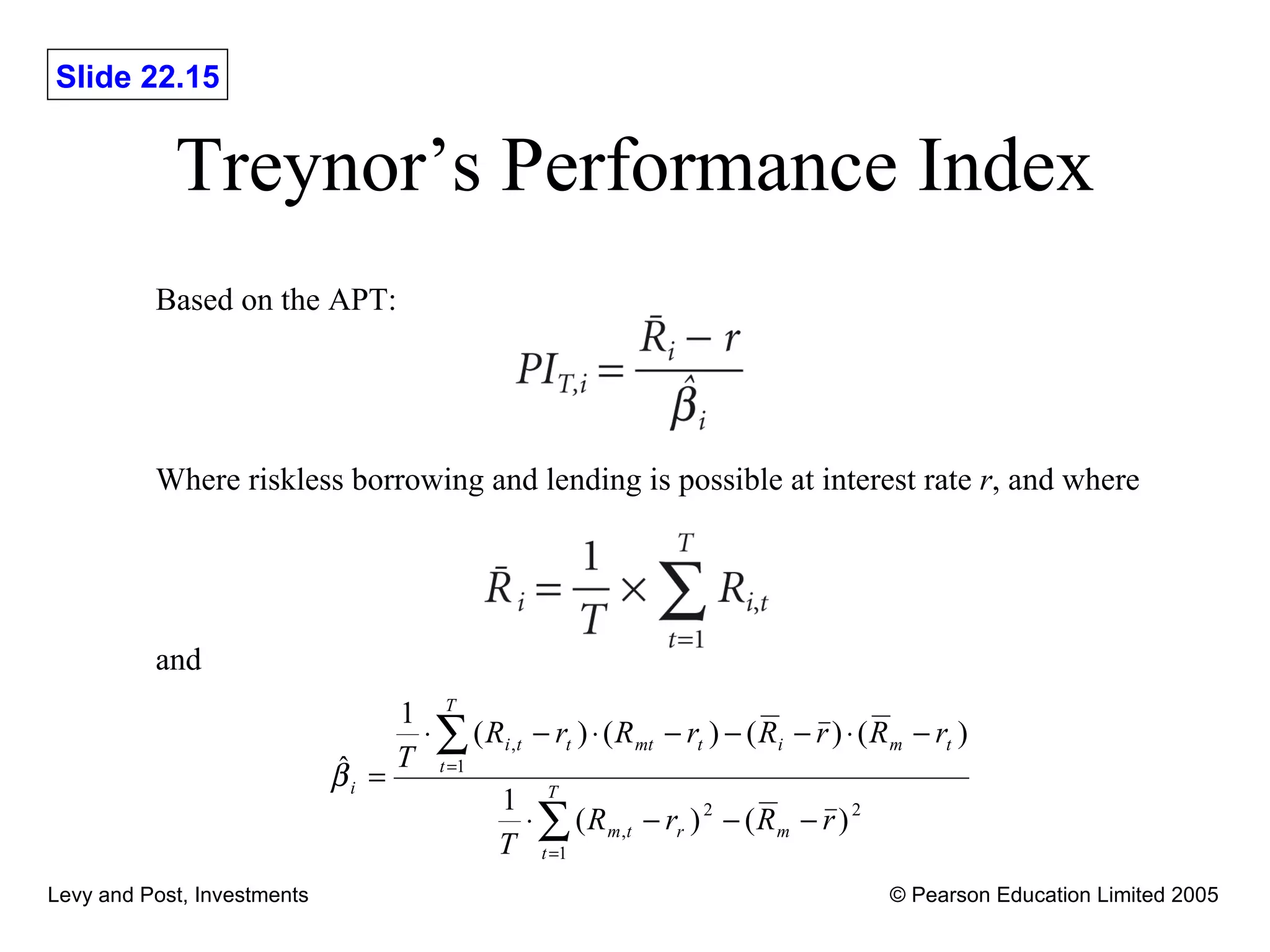

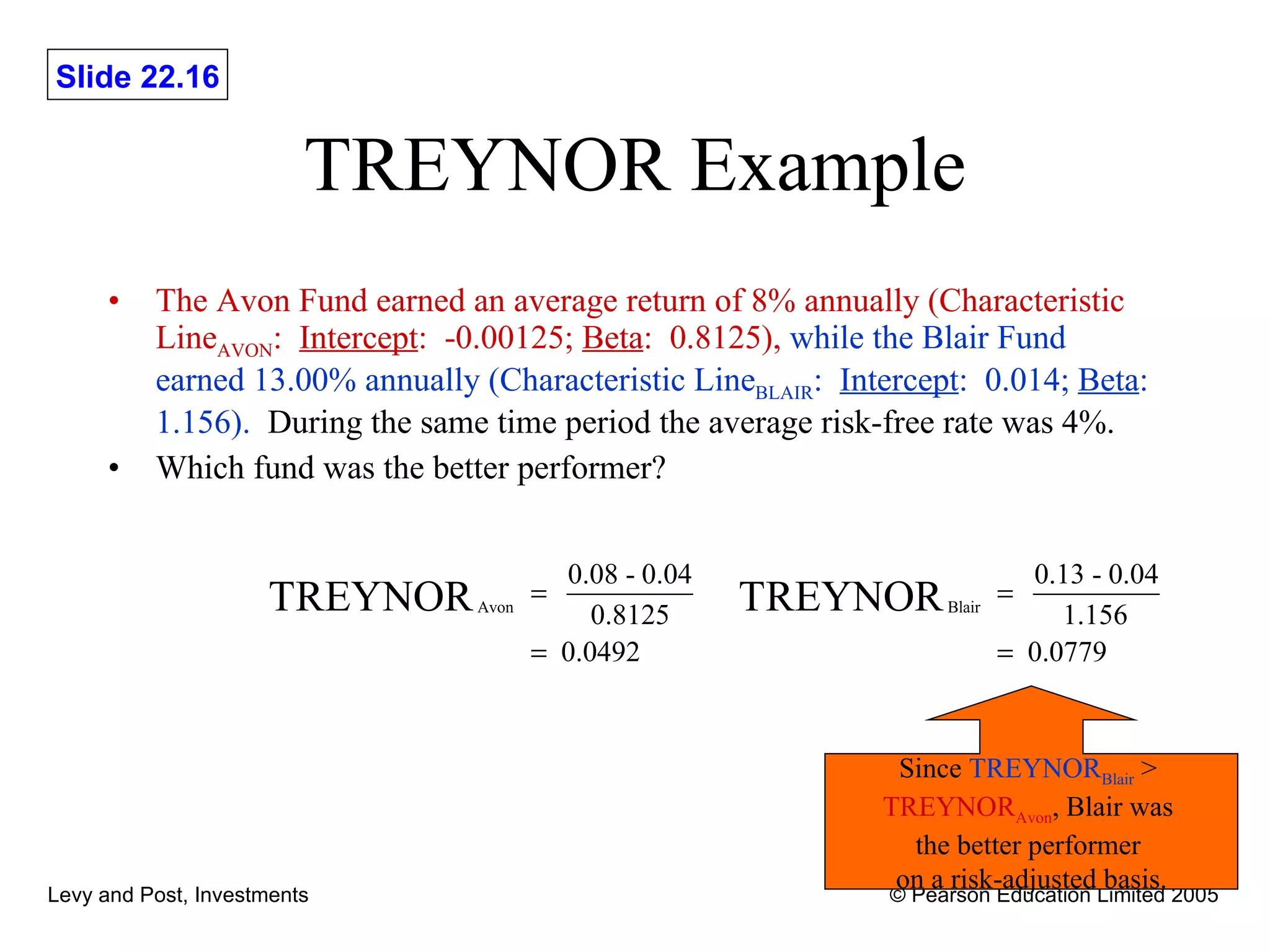

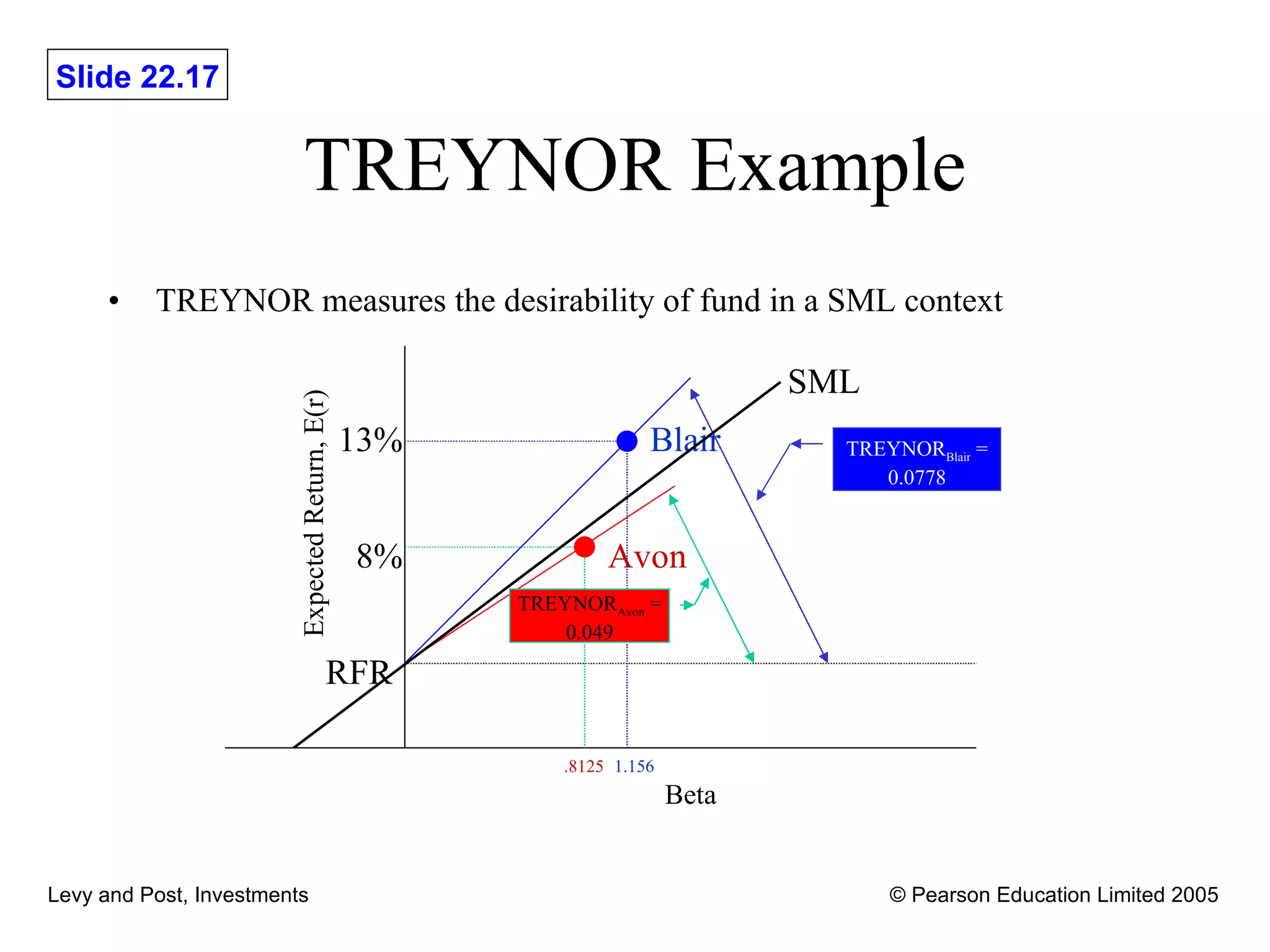

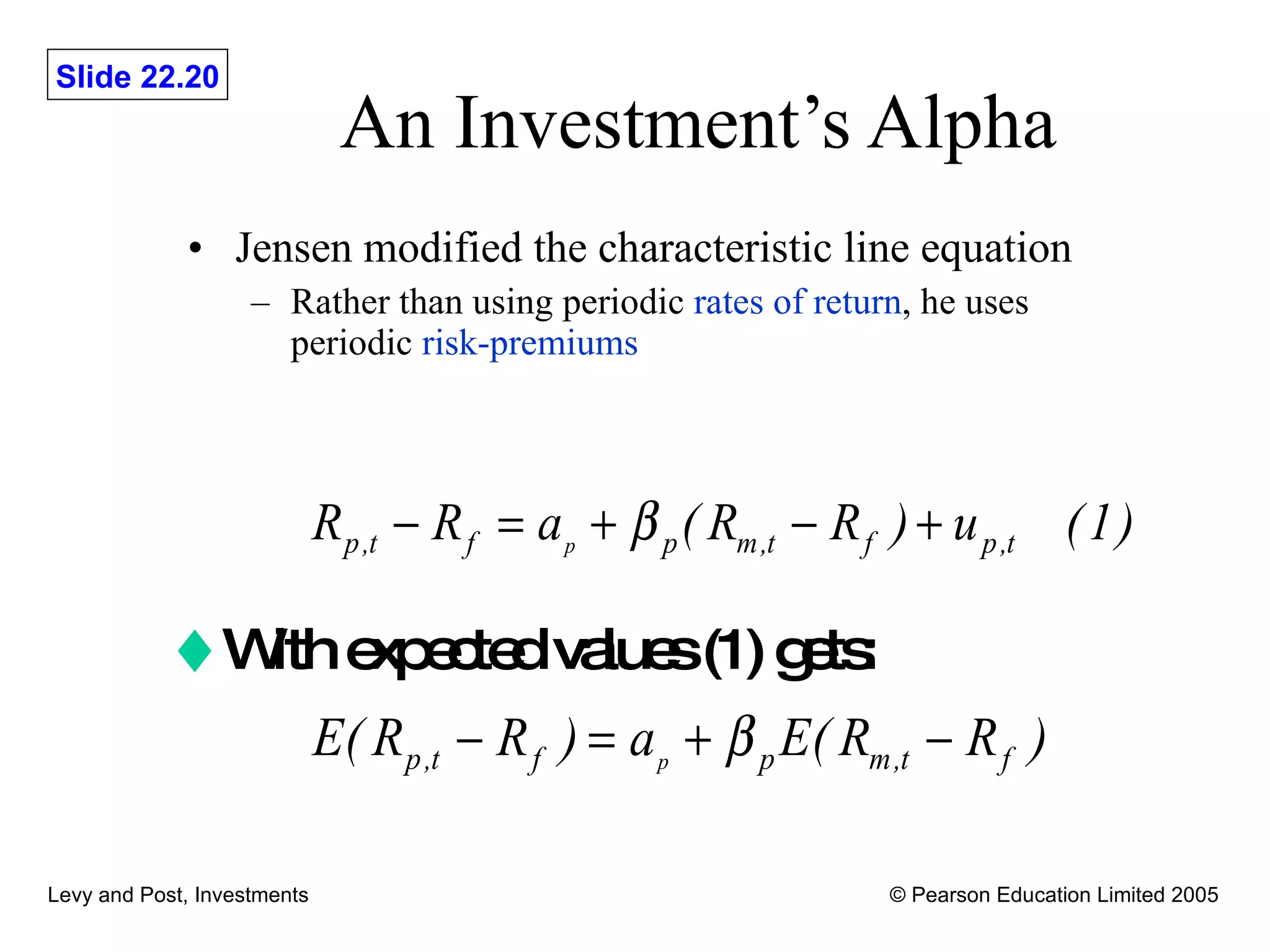

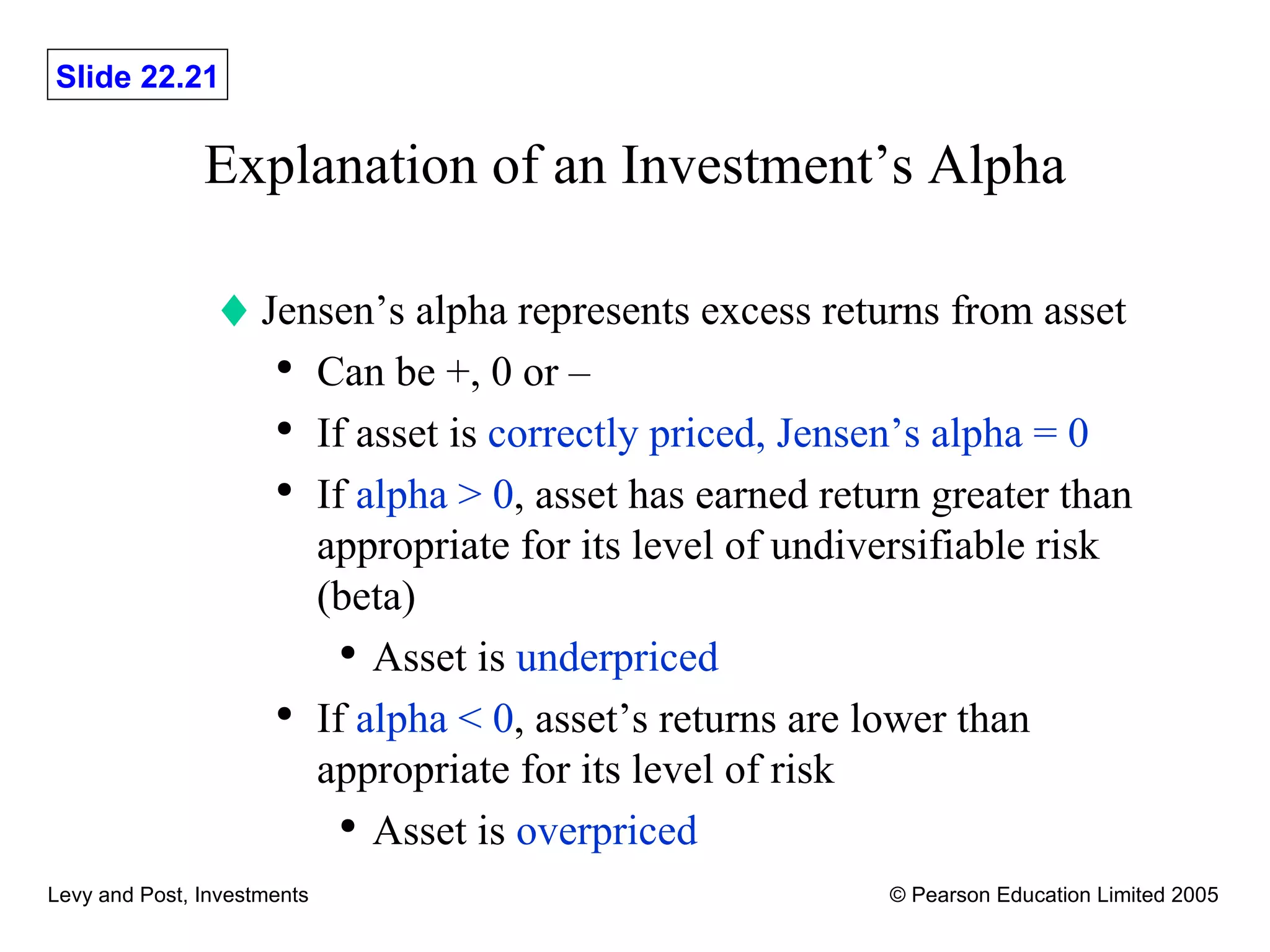

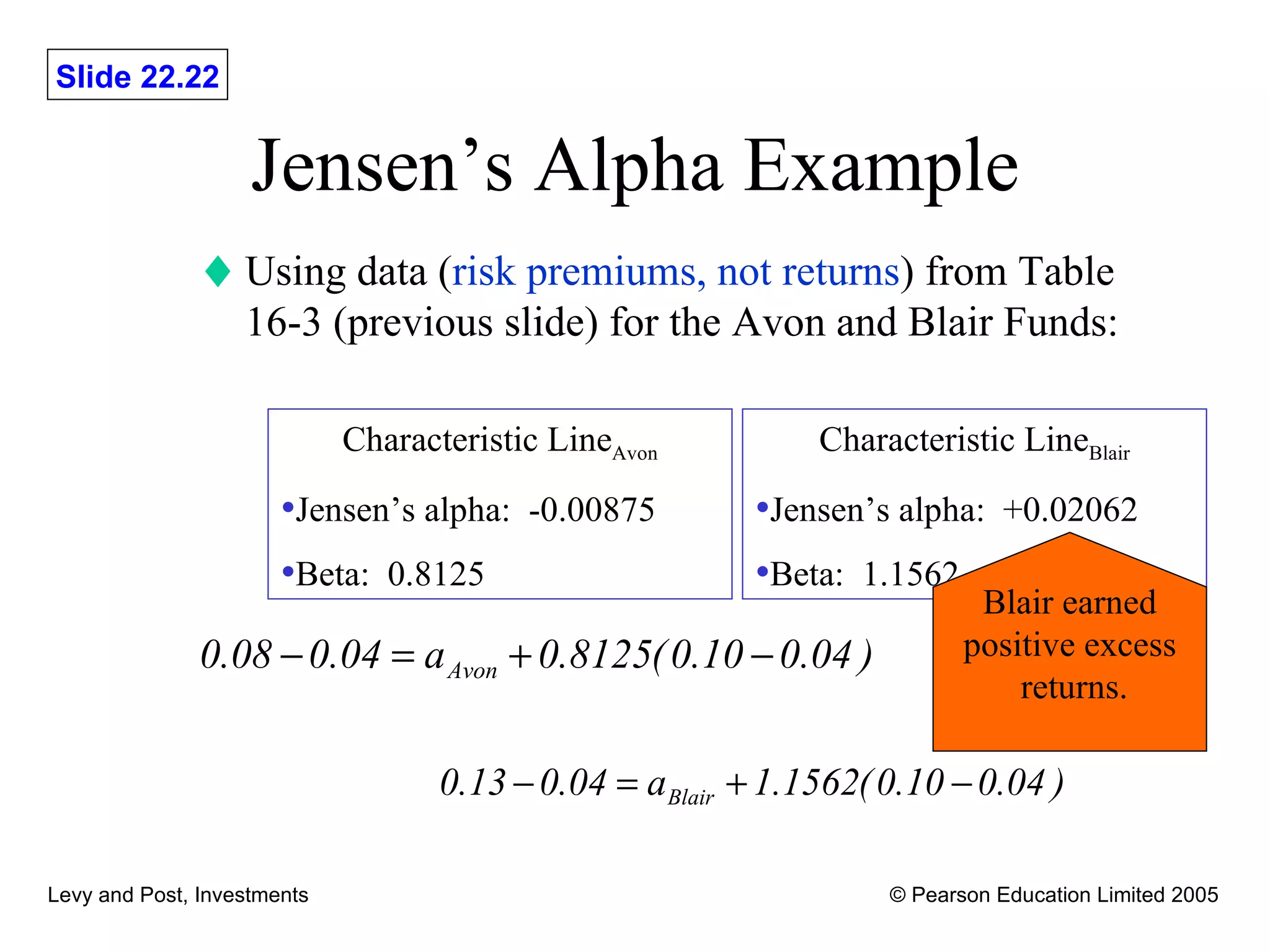

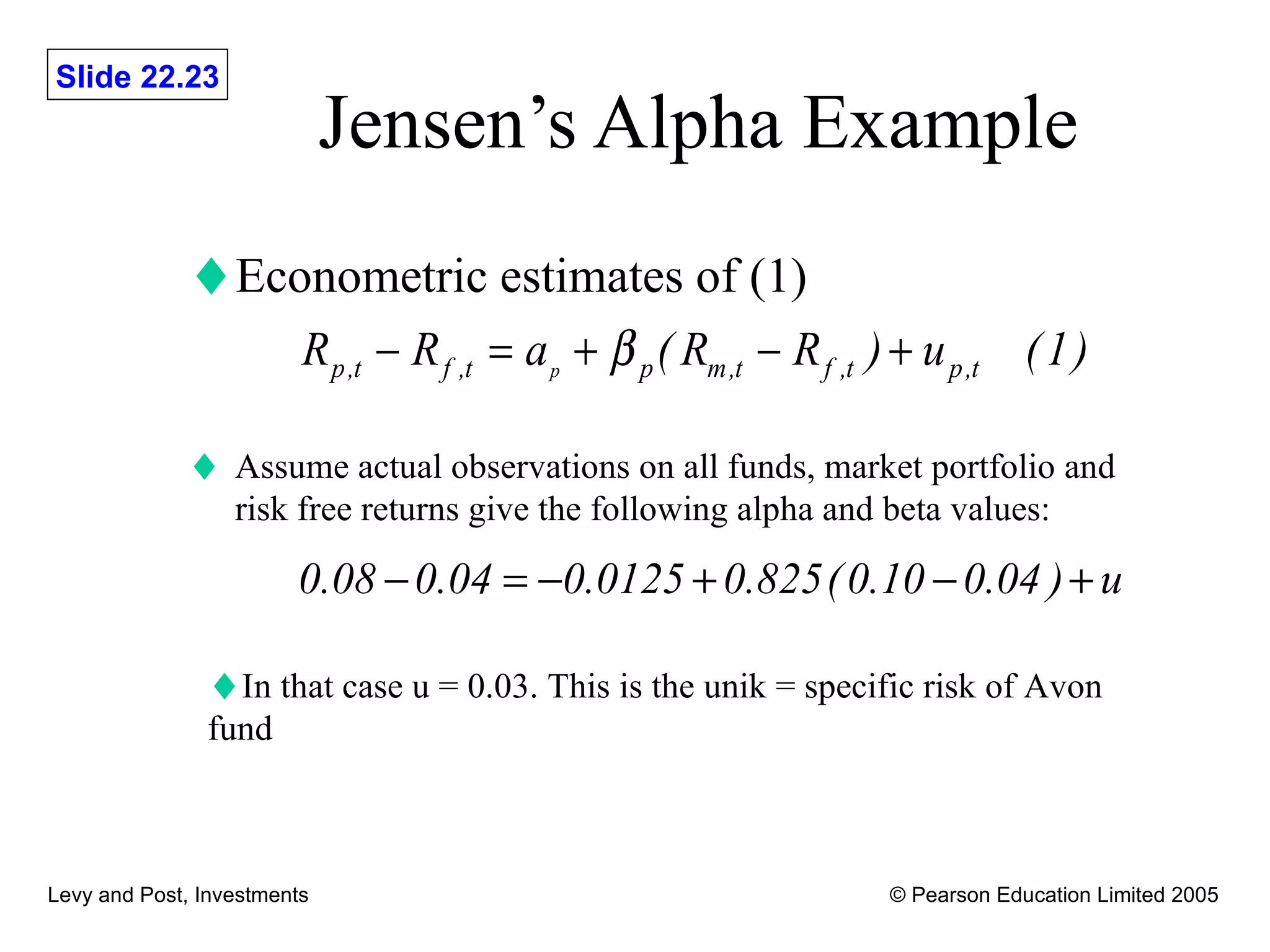

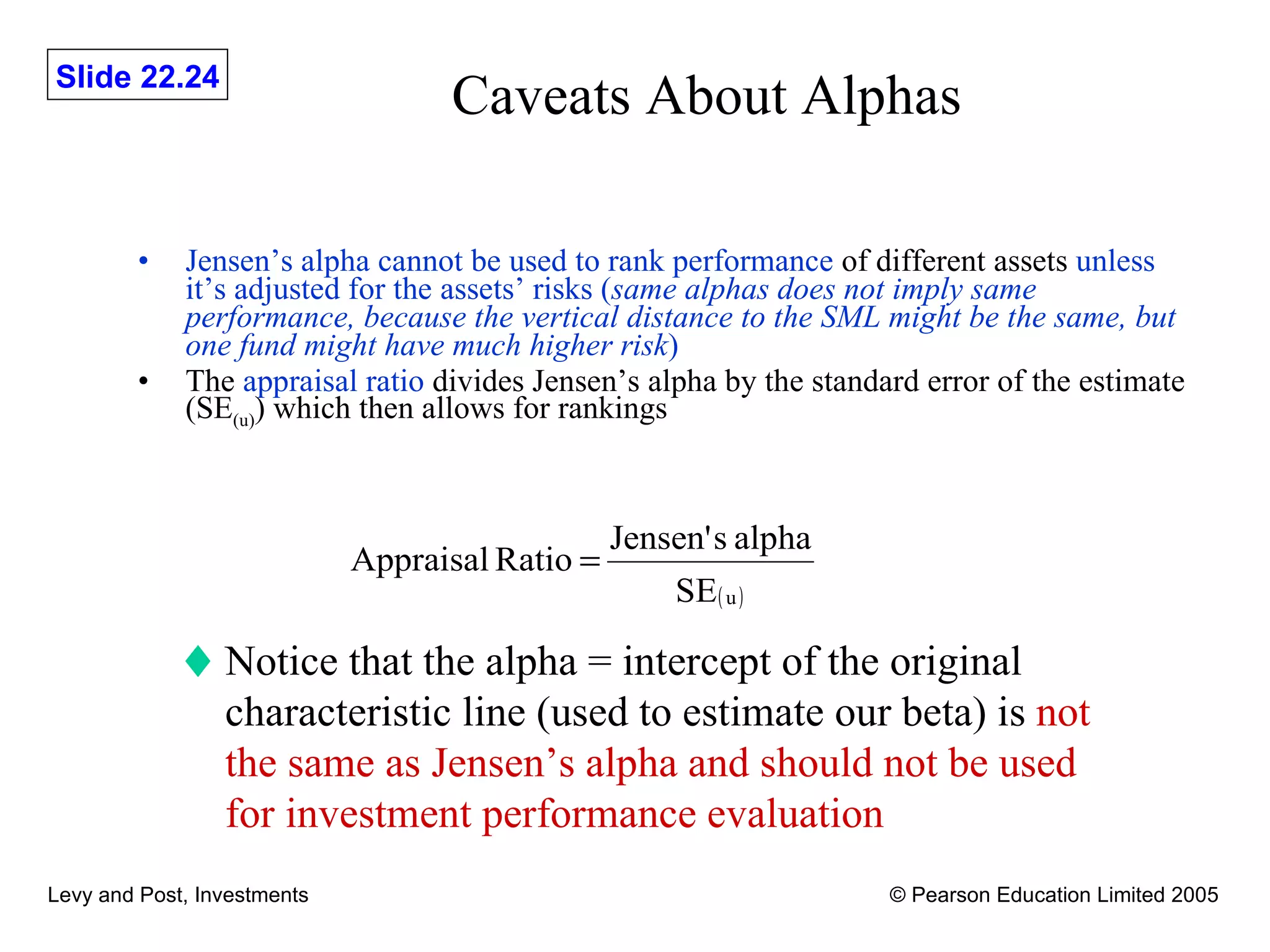

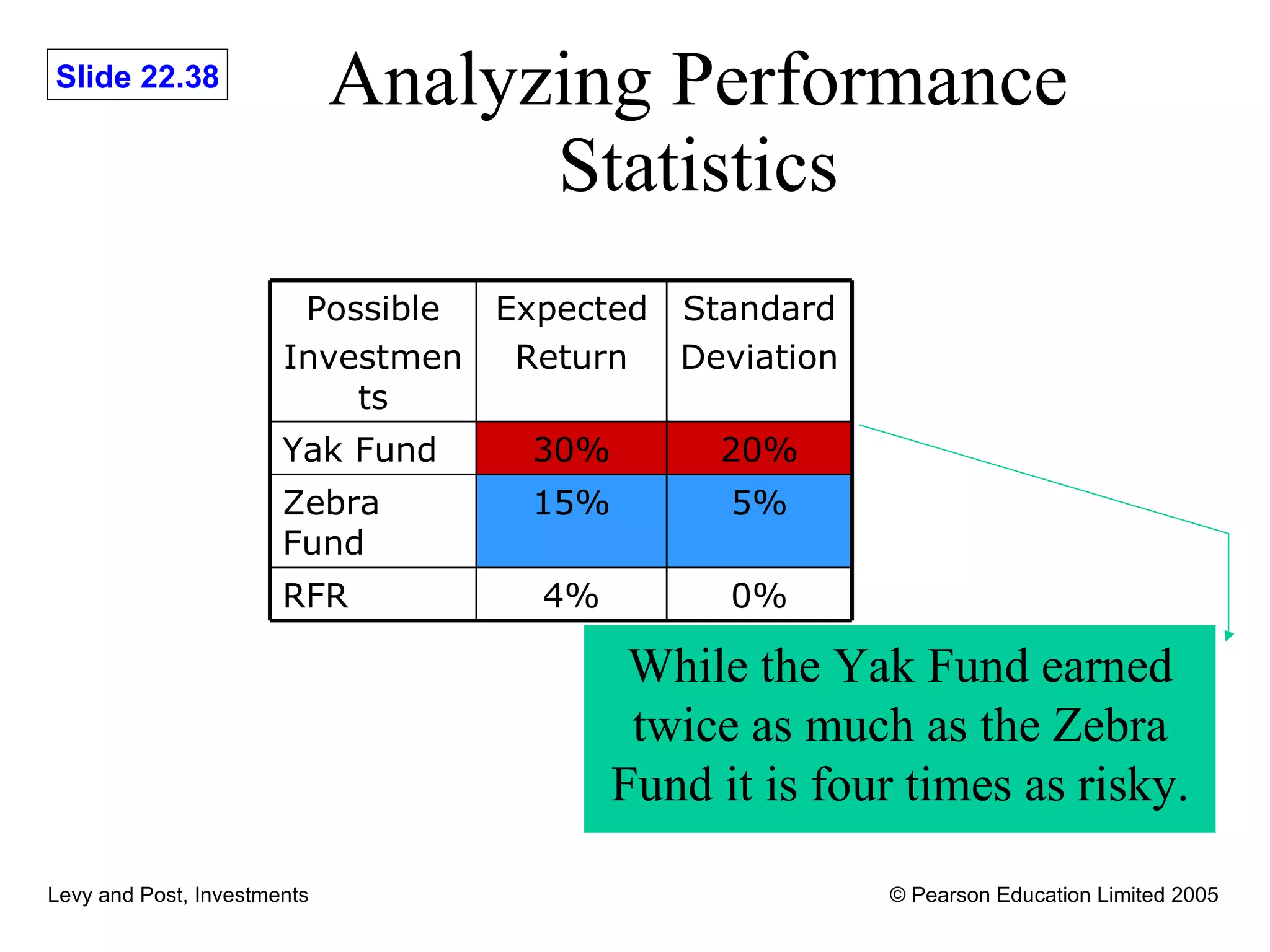

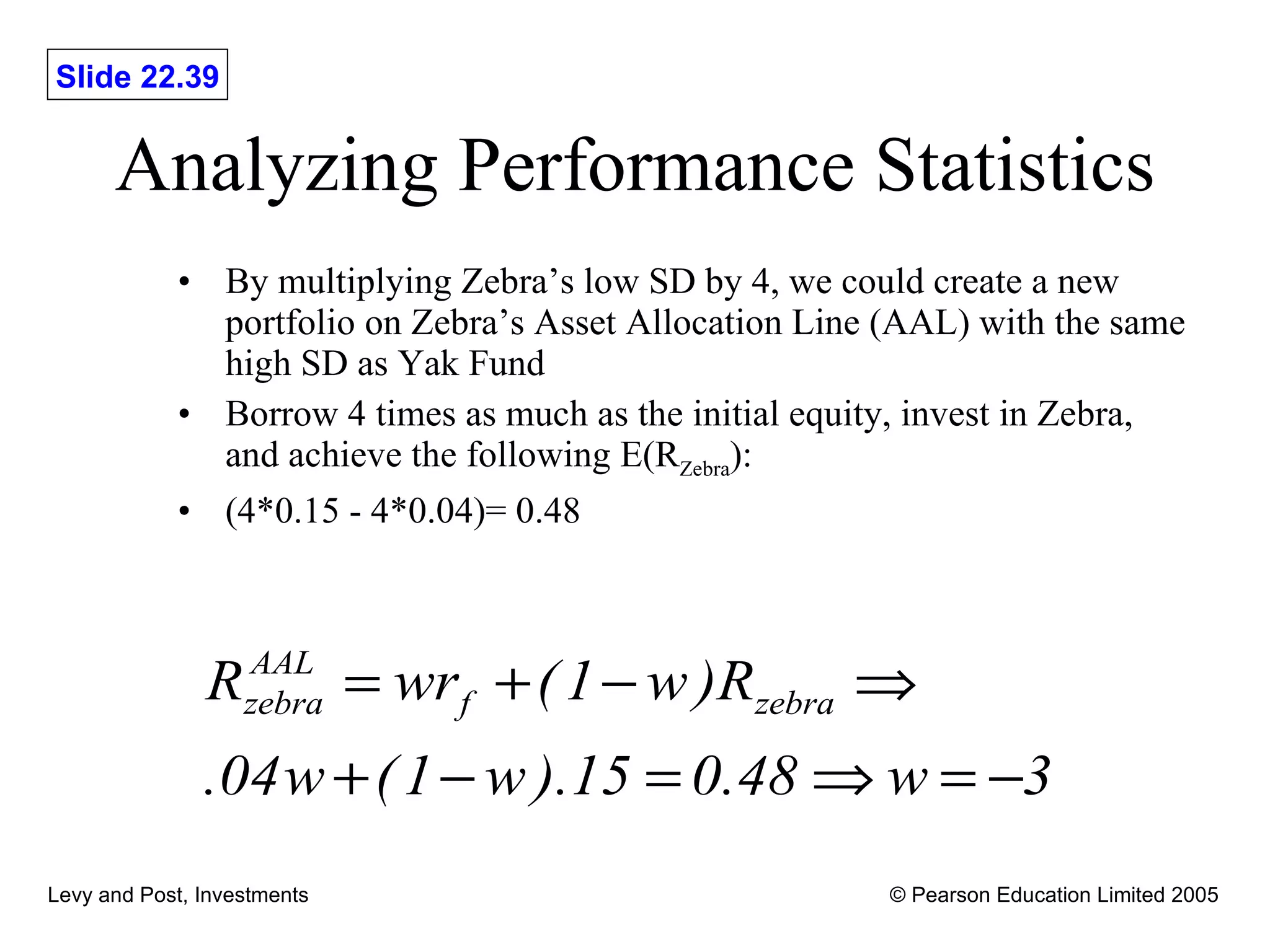

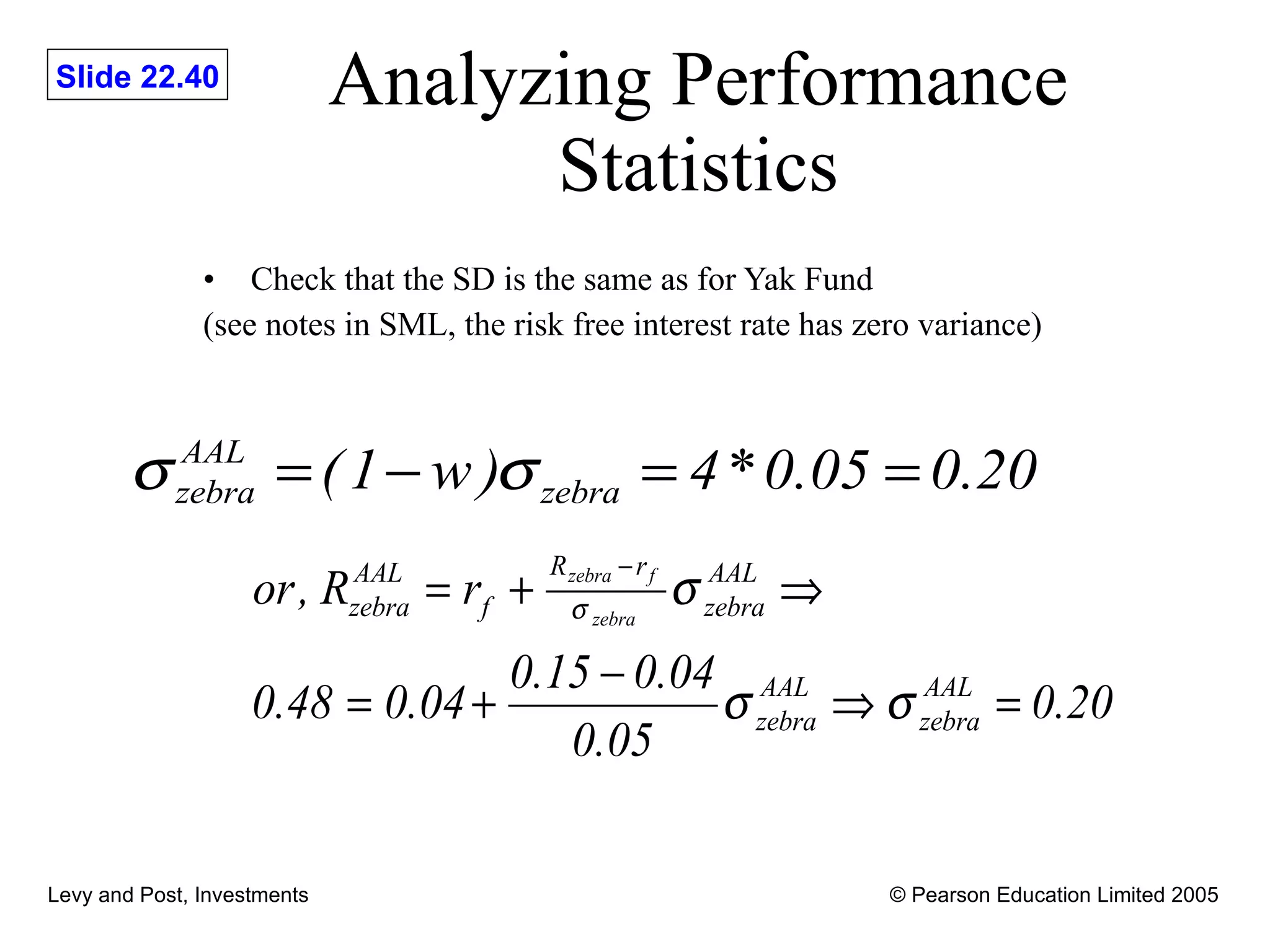

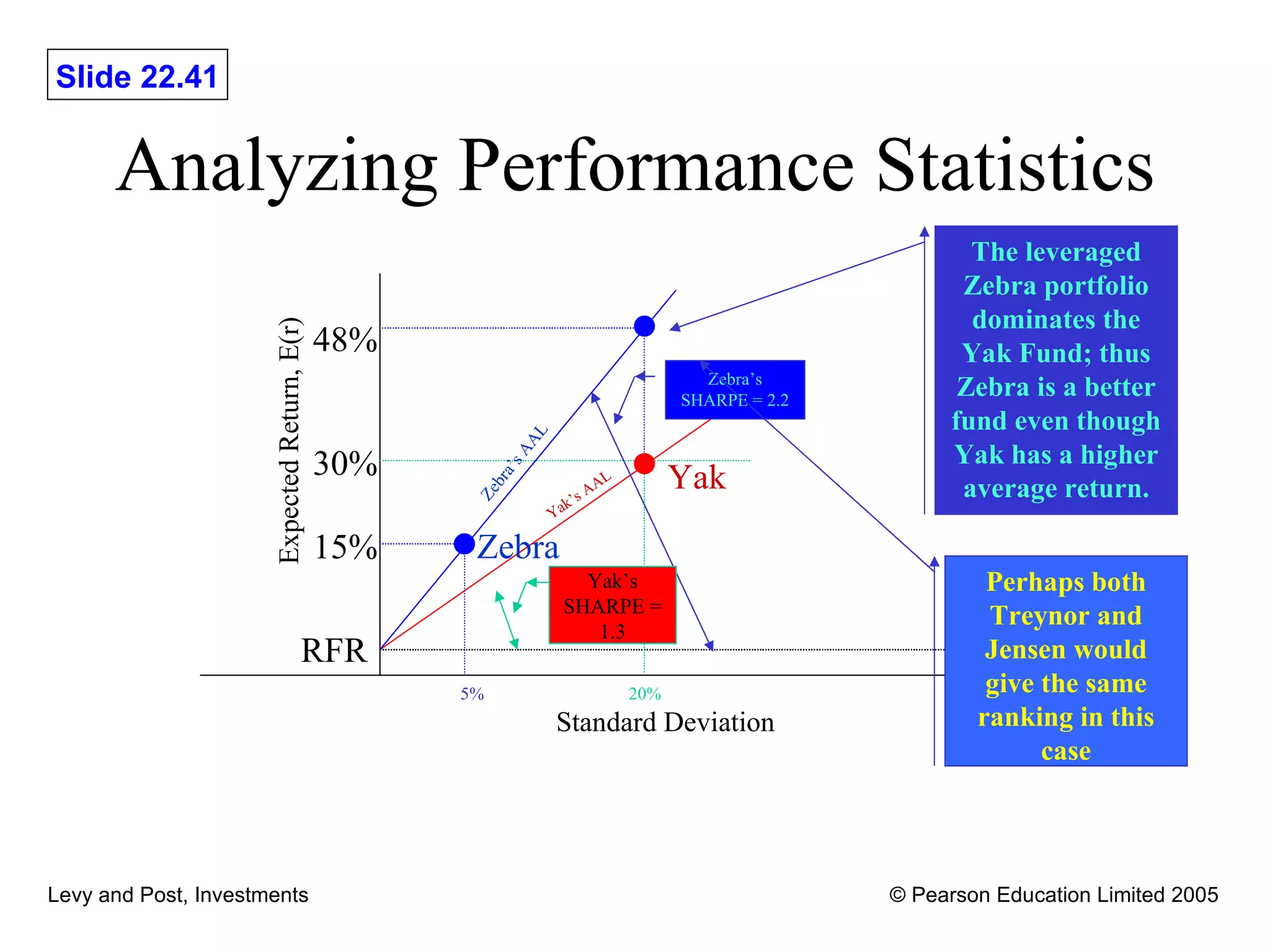

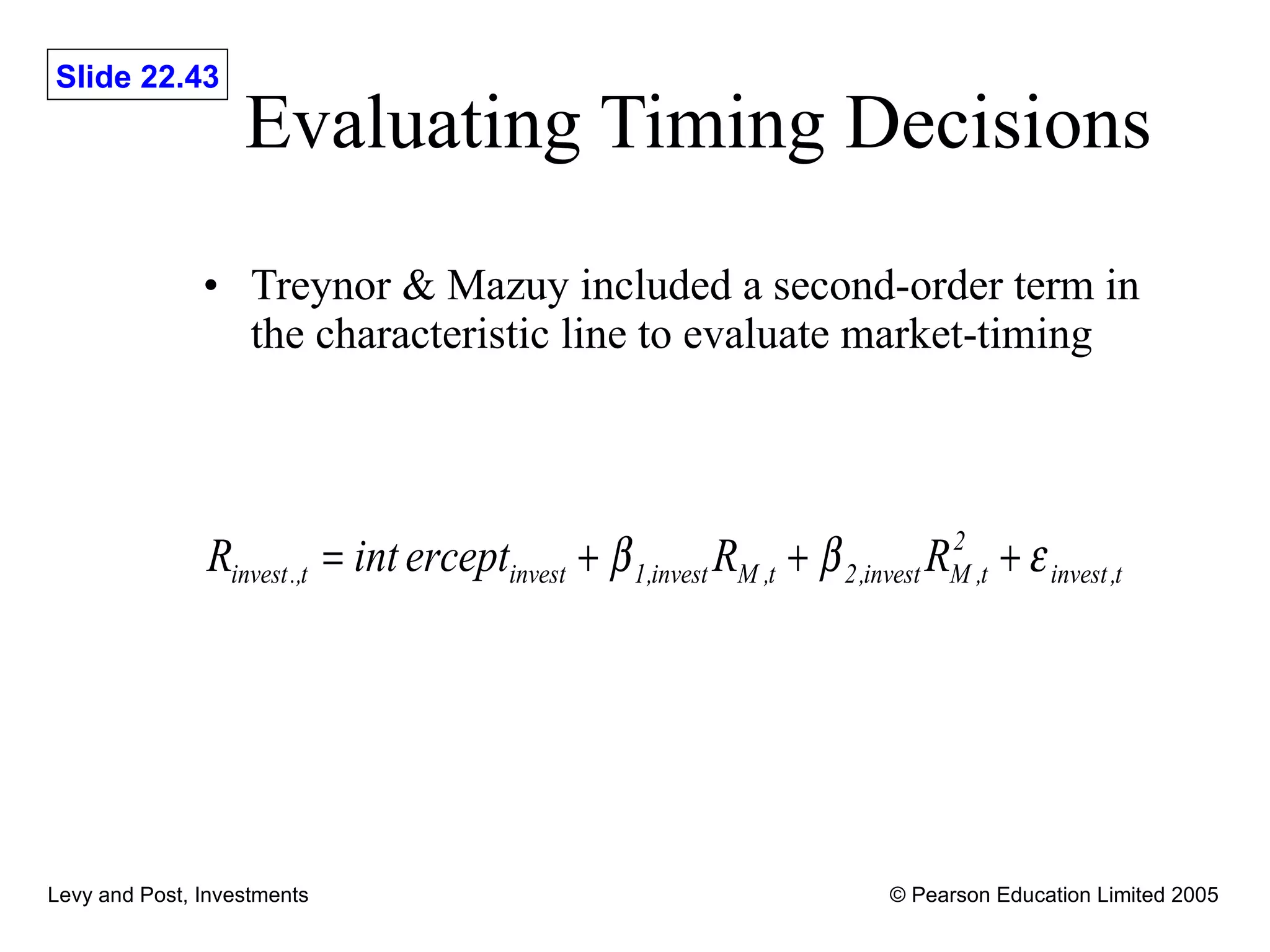

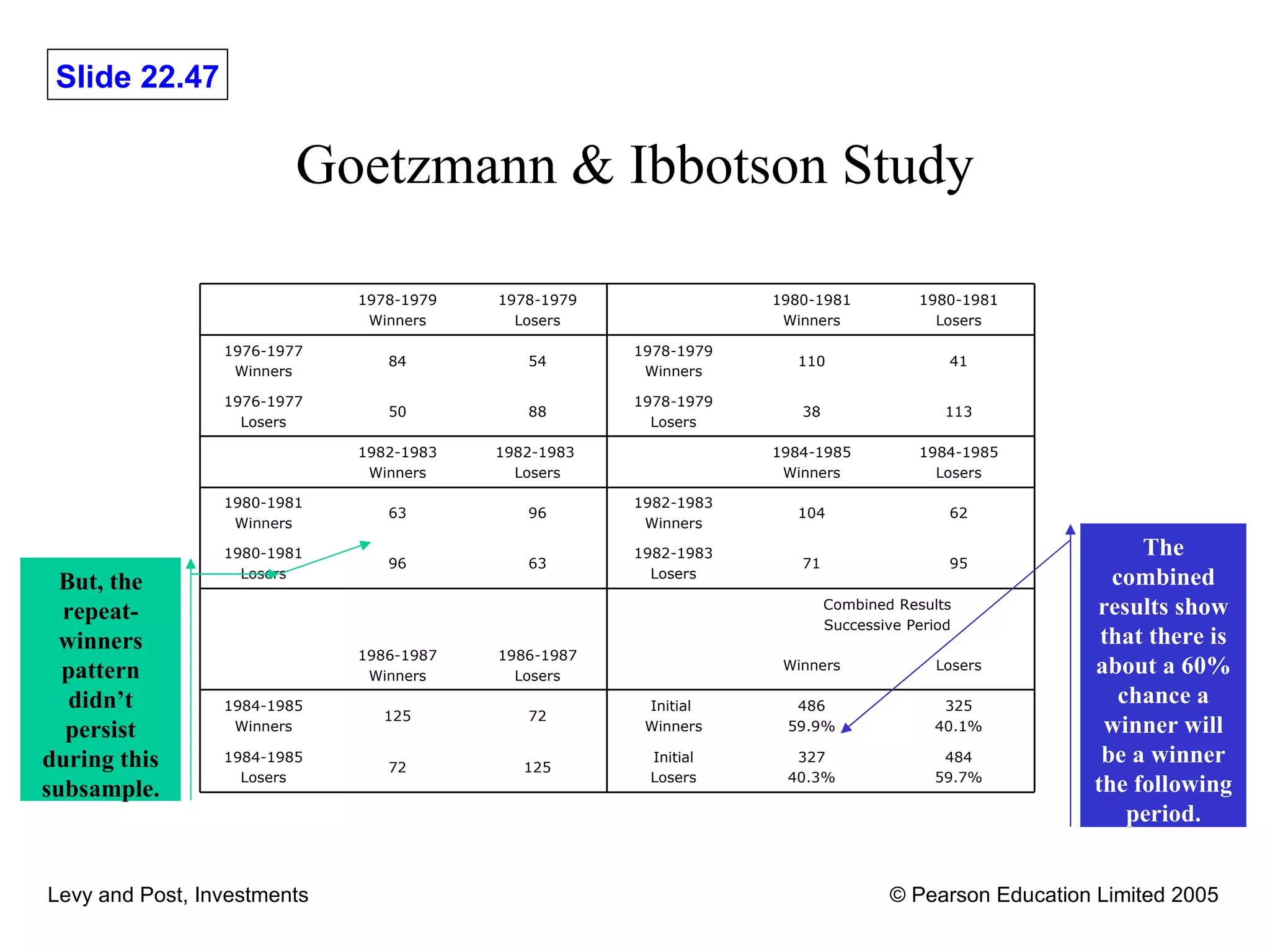

This document discusses various methods for evaluating investment performance, including risk-adjusted performance indexes. It describes tools like Sharpe's performance index, Treynor's performance index, and Jensen's performance index that measure performance based on risk and return. It also cautions that performance evaluation is historical and notes difficulties in accurately measuring risk and performance.