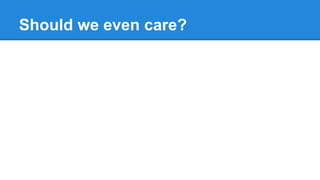

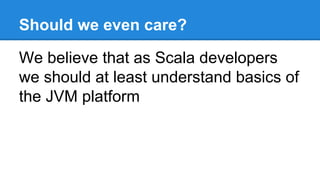

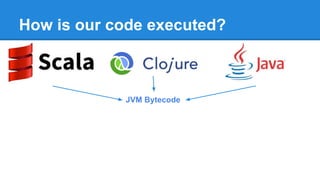

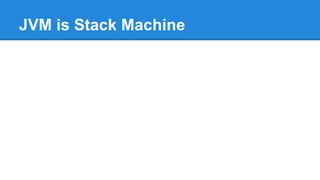

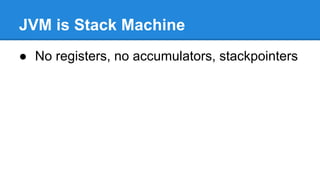

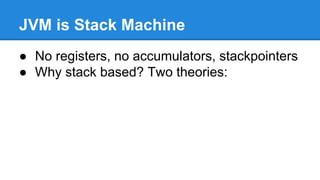

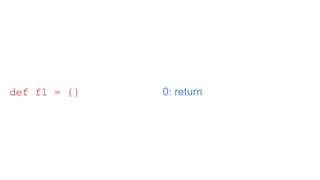

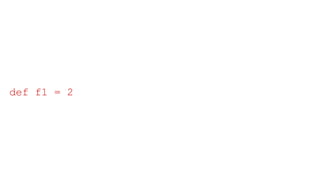

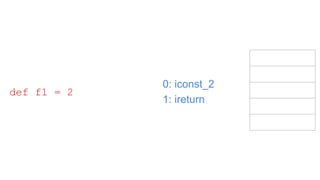

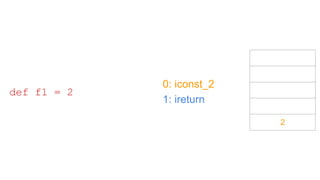

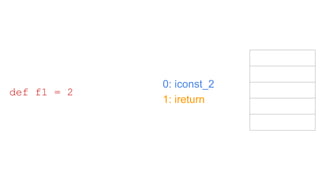

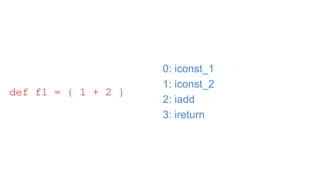

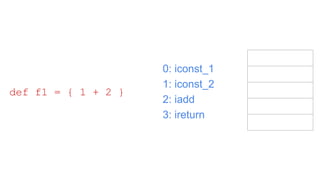

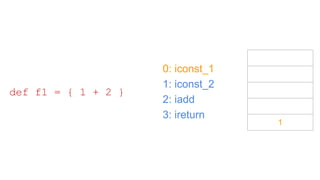

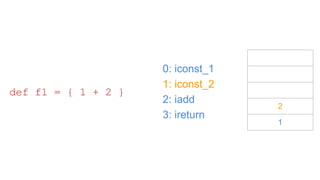

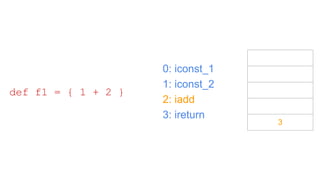

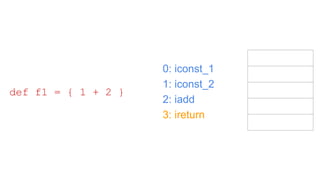

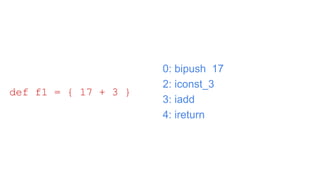

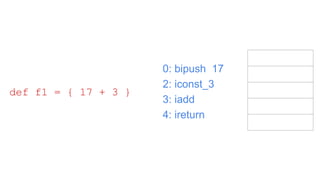

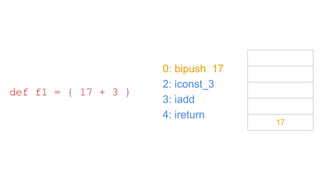

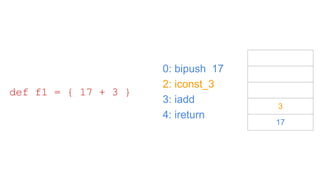

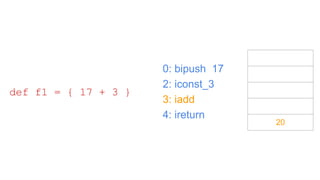

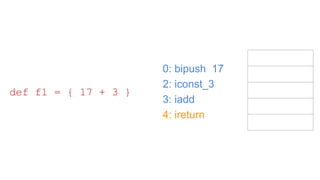

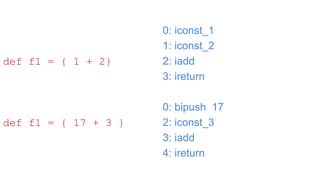

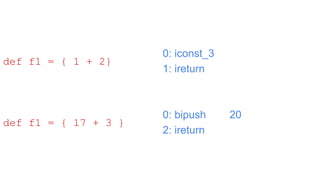

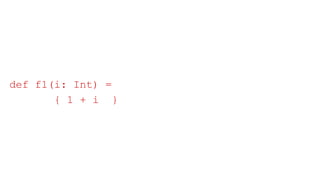

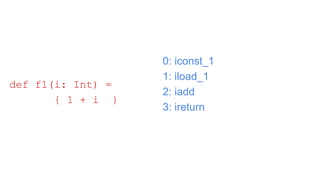

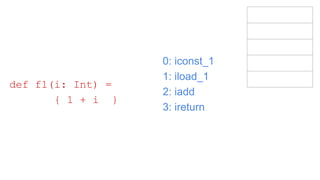

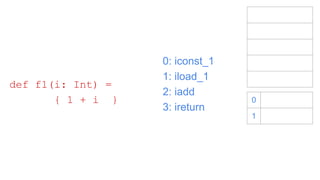

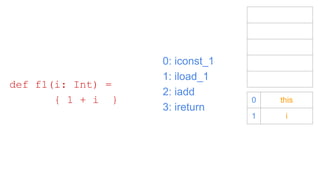

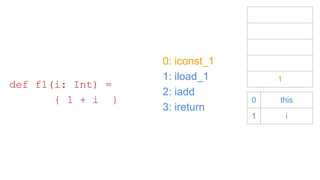

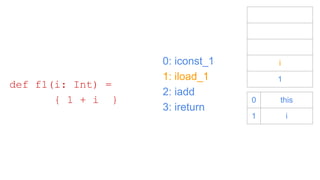

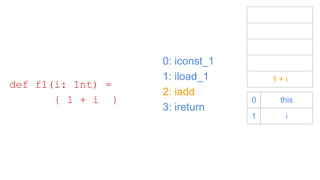

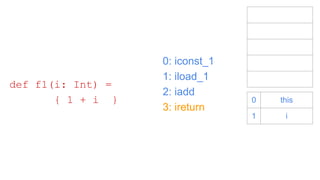

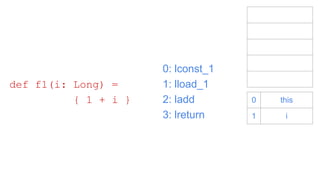

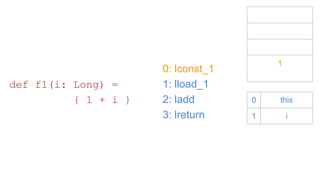

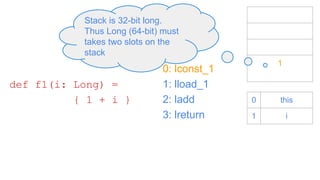

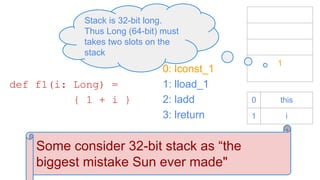

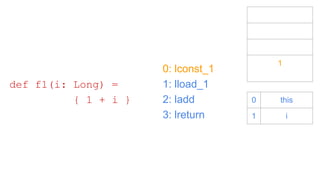

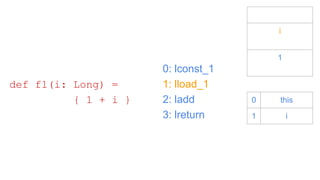

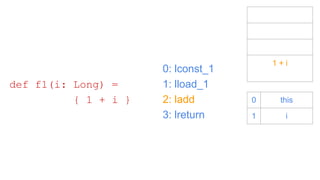

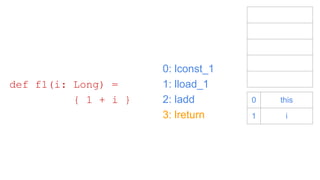

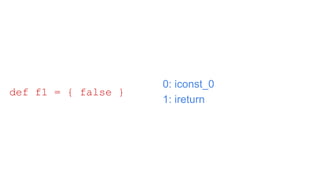

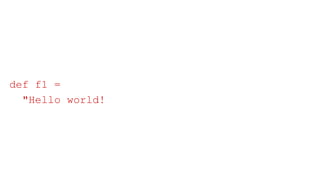

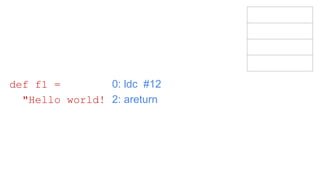

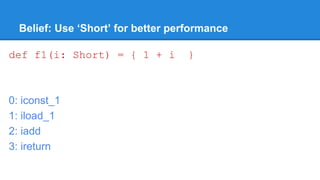

The document discusses the importance for Scala developers to understand the basics of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) platform that Scala code runs on. It provides examples of Java bytecode produced from simple Scala code snippets to demonstrate how code is executed by the JVM. Key points made include that the JVM is a stack-based virtual machine that compiles source code to bytecode instructions, and that understanding the level below the code helps developers write more efficient, robust and performant code.

![Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strongtalk

“Work began in 1994 and they completed an

implementation in 1996. The company was bought by

Sun Microsystems in 1997, and the team got focused

on Java, releasing the HotSpot virtual machine,[3] and

work on Strongtalk stalled.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-45-320.jpg)

![G1object MyBenchmarkLatency {

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

class Memory {

val heap = new Array[Array[Byte]](100)

}

}

@State(Scope.Thread)

class MyBenchmarkLatency {

val rand = new Random()

val base = 3000

val randBase = 100

def baseline() = ...

def testMethod(memory: Memory) = ...

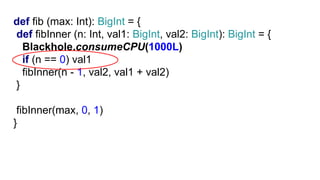

def fib (max: Int): BigInt = …

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-239-320.jpg)

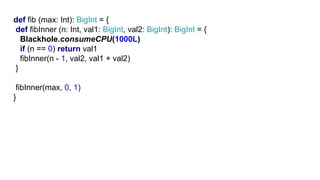

val result: BigInt =

fib(base + rand.nextInt(randBase))

for (i <- 0 until 100) memory.heap(i) = null

result + rand.nextInt()

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-240-320.jpg)

val result =

fib(base + rand.nextInt(randBase))

for (i <- 0 until 100) memory.heap(i) = null

result + rand.nextInt()

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-241-320.jpg)

![G1object MyBenchmarkBatch {

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

class Memory {

val heap = new Array[Array[Byte]](100)

}

}

@State(Scope.Thread)

class MyBenchmarkBatch {

@Param(Array("10"))

var offset: Int = _

var startPtr: Int = 0

var endPtr: Int = 0

def testMethod(memory: Memory) = ...

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-247-320.jpg)

![G1@Benchmark

@BenchmarkMode(Array(Mode.Throughput))

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.SECONDS)

def testMethod(memory: Memory) {

for (i <- startPtr until startPtr + offset) memory.heap(i % 100) = new Array[Byte]

(1024)

startPtr += offset

Blackhole.consumeCPU(1000L)

for (i <- endPtr until endPtr + offset) memory.heap(i % 100) = null

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-248-320.jpg)

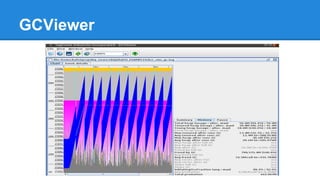

![ParallelGC

[PSYoungGen: 117951K->17408K(128512K)] 163328K->83265K(217600K),

0,0356419 secs] [Times: user=0,03 sys=0,11, real=0,04 secs]

0,703: [Full GC (Ergonomics) [PSYoungGen: 17408K->0K(128512K)]

[ParOldGen: 65857K->77121K(135168K)] 83265K->77121K(263680K),

[Metaspace: 7223K->7223K(1056768K)], 0,0401522 secs] [Times: user=0,12

sys=0,02, real=0,04 secs]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-273-320.jpg)

![CMS

1,881: [GC (Allocation Failure) 1,881: [ParNew

Desired survivor size 1081344 bytes, new threshold 1 (max 6)

- age 1: 2097184 bytes, 2097184 total

: 18760K->2048K(19008K), 0,0152627 secs] 705206K->704878K(725612K),

0,0153456 secs] [Times: user=0,05 sys=0,02, real=0,01 secs]

1,902: [GC (Allocation Failure) 1,902: [ParNew: 18927K->18927K(19008K),

0,0000199 secs]1,902: [CMS1,902: [CMS-concurrent-abortable-preclean:

0,072/0,678 secs] [Times: user=2,26 sys=0,20, real=0,68 secs]

(concurrent mode failure): 702830K->90458K(706604K), 0,0536025 secs]

721757K->90458K(725612K), [Metaspace: 7235K->7235K(1056768K)],

0,0545283 secs] [Times: user=0,05 sys=0,00, real=0,05 secs]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-274-320.jpg)

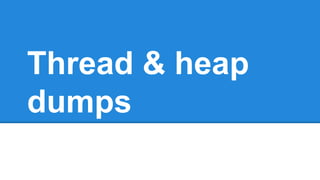

![How to make thread dump

● jstack [-Flm] <pid>

● kill -3 <pid>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-278-320.jpg)

![But what with GC logs?"org.openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.baseline-jmh-worker-3"

#13 daemon prio=5 os_prio=0 tid=0x00007fb5c0243000 nid=0x22fb runnable

[0x00007fb5a6b50000]

java.lang.Thread.State: RUNNABLE at org.openjdk.jmh.samples.

MyBenchmarkLatency.fibInner$1(MyBenchmarkLatency.scala:56) at org.

openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.fib(MyBenchmarkLatency.scala:

59) at org.openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.baseline

(MyBenchmarkLatency.scala:35) at org.openjdk.jmh.samples.generated.

MyBenchmarkLatency_baseline.baseline_AverageTime

(MyBenchmarkLatency_baseline.java:124)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-279-320.jpg)

![But what with GC logs?

"org.openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.baseline-jmh-worker-3"

#13 daemon prio=5 os_prio=0 tid=0x00007fb5c0243000 nid=0x22fb runnable

[0x00007fb5a6b50000]

java.lang.Thread.State: RUNNABLE

at java.math.BigInteger.add(BigInteger.java:1315)

at java.math.BigInteger.add(BigInteger.java:1221)

at scala.math.BigInt.$plus(BigInt.scala:203)

at org.openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.fibInner$1

(MyBenchmarkLatency.scala:56)

at org.openjdk.jmh.samples.MyBenchmarkLatency.fib

(MyBenchmarkLatency.scala:59)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-280-320.jpg)

val result: BigInt =

fib(base + rand.nextInt(randBase))

for (i <- 0 until 100) memory.heap(i) = null

result + rand.nextInt()

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/knowyourplatform-150914171628-lva1-app6892/85/Know-your-platform-7-things-every-scala-developer-should-know-about-jvm-281-320.jpg)