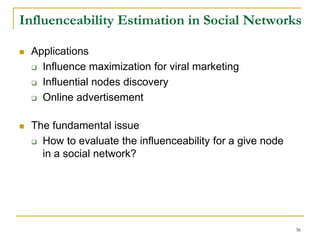

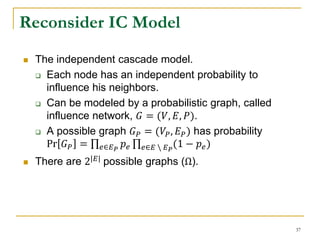

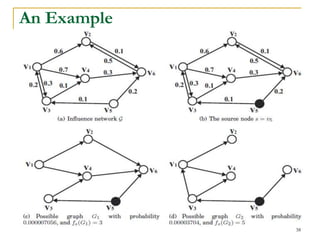

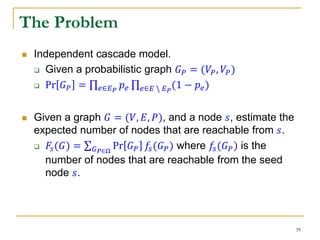

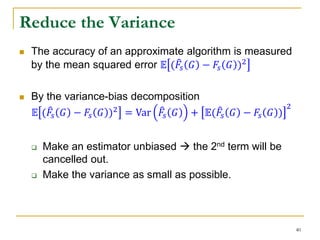

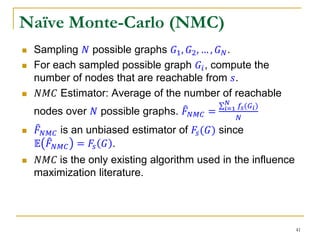

This document discusses influenceability estimation in social networks. It describes the independent cascade model of influence diffusion, where each node has an independent probability of influencing its neighbors. The problem is to estimate the expected number of nodes reachable from a given seed node. The document presents the naive Monte Carlo (NMC) approach, which samples possible graphs and averages the number of reachable nodes over the samples. While NMC provides an unbiased estimator, it has high variance. The document aims to reduce the variance to improve estimation accuracy.

![An Existing Approach

MB [Mishra and Bhattacharya, WWW’11]

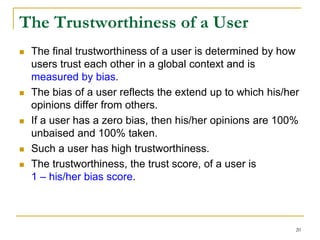

The trustworthiness of a user cannot be trusted,

because MB treats the bias of a user by relative

differences between itself and others.

If a user gives all his/her friends a much higher trust

score than the average of others, and gives all his/her

foes a much lower trust score than the average of

others, such differences cancel out. This user has

zero bias and can be 100% trusted.

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-21-320.jpg)

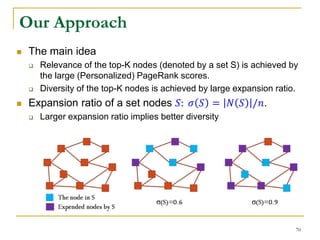

![Our Approach

We use two vectors, 𝑏 and 𝑟, for bias and prestige.

The 𝑏𝑗 = (𝑓(𝑟)) 𝑗 denotes the bias of node 𝑗, where 𝑟 is

the prestige vector of the nodes, and 𝑓(𝑟) is a vector-

valued contractive function. (𝑓 𝑟 ) 𝑗 denotes the 𝑗-th

element of vector 𝑓(𝑟).

Let 0 ≤ 𝑓(𝑟) ≤ 𝑒, and 𝑒 = [1, 1, … , 1] 𝑇

For any 𝑥, 𝑦 ∈ 𝑅 𝑛, the function 𝑓: 𝑅 𝑛 → 𝑅 𝑛 is a vector-

valued contractive function if the following condition

holds,

𝑓 𝑥 – 𝑓 𝑦 ≤ 𝜆 ∥ 𝑥 − 𝑦 ∥∞ 𝑒

where 𝜆 ∈ [0,1) and ∥∙∥∞ denotes the infinity norm.

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-26-320.jpg)

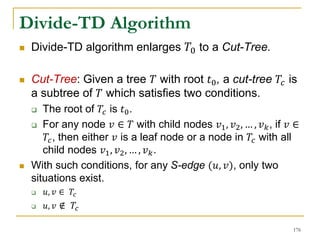

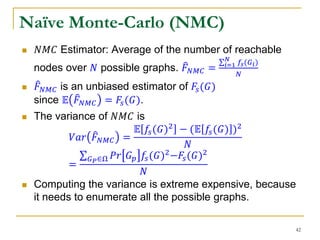

![Naïve Monte-Carlo (NMC)

In practice, it resorts to an unbiased estimator of 𝑉𝑎𝑟( 𝐹 𝑁𝑀𝐶).

The variance of 𝑁𝑀𝐶 is

𝑉𝑎𝑟 𝐹 𝑁𝑀𝐶 =

𝑖=1

𝑁

(𝑓𝑠 𝐺𝑖 − 𝐹 𝑁𝑀𝐶)2

𝑁 − 1

But, 𝑉𝑎𝑟 𝐹 𝑁𝑀𝐶 may be very large, because 𝑓𝑠 𝐺𝑖 fall into

the interval [0, 𝑛 − 1].

The variance can be up to 𝑂(𝑛2).

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-43-320.jpg)

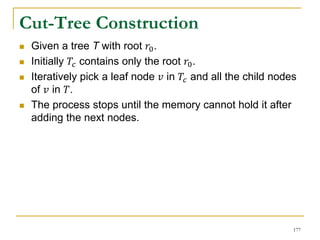

![A Recursive Estimator [Jin et al. VLDB’11]

Randomly select 1 edge to partition the probability

space (the set of all possible graphs) into 2 strata

(2 subsets)

The possible graphs in the first subset include

the selected edge.

The possible graphs in the second subset do

not include the selected edge.

Sample possible graphs in each stratum 𝑖 with a

sample size 𝑁𝑖 proportioning to the probability of

that stratum.

Recursively apply the same idea in each stratum.

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-45-320.jpg)

![A Recursive Estimator [Jin et al. VLDB’11]

Advantages:

unbiased estimator with a smaller variance.

Limitations:

Select only one edge for stratification, which is not

enough to significantly reduce the variance.

Randomly select edges, which results in a possible

large variance.

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-46-320.jpg)

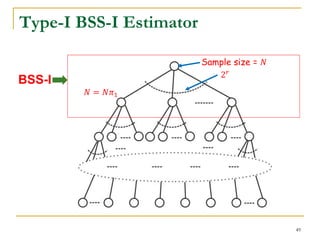

![Type-I Basic Estimator (BSS-I)

Select 𝑟 edges to partition the probability space (all the

possible graphs) into 2 𝑟

strata.

Each stratum corresponds to a probability subspace

(a set of possible graphs).

Let 𝜋𝑖 = Pr[𝐺 𝑃 ∈ Ω𝑖].

How to select 𝑟 edges: BFS or random

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-48-320.jpg)

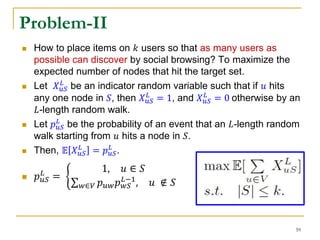

![ The two problems are a random walk problem.

𝐿-length random walk model where the path length of

random walks is bounded by a nonnegative number 𝐿.

A random walk in general can be considered as 𝐿 = ∞.

Let 𝑍 𝑢

𝑡

be the position of an 𝐿-length random walk,

starting from node 𝑢, at discrete time 𝑡.

Let 𝑇𝑢𝑣

𝐿 be a random walk variable.

𝑇𝑢𝑣

𝐿

≜ min{min 𝑡: 𝑍 𝑢

𝑡

= v, t ≥ 0}, 𝐿

The hitting time ℎ 𝑢𝑣

𝐿 can be defined as the expectation

of 𝑇𝑢𝑣

𝐿 .

ℎ 𝑢𝑣

𝐿

= 𝔼[𝑇𝑢𝑣

𝐿

]

The Random Walk

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-55-320.jpg)

![The Random-Walk Domination

Consider a set of nodes 𝑆. If a random walk from 𝑢

reaches 𝑆 by an 𝐿-length random walk, we say

𝑆 dominates 𝑢 by an 𝐿-length random walk.

Generalized hitting time over a set of nodes, 𝑆. The

hitting time ℎ 𝑢𝑆

𝐿

can be defined as the expectation of a

random walk variable 𝑇𝑢𝑆

𝐿

.

𝑇𝑢𝑆

𝐿

≜ min{min 𝑡: 𝑍 𝑢

𝑡

∈ 𝑆, t ≥ 0}, 𝐿

ℎ 𝑢𝑆

𝐿

= 𝔼[𝑇𝑢𝑆

𝐿

]

It can be computed recursively.

ℎ 𝑢𝑆

𝐿

=

0, 𝑢 ∈ 𝑆

1 + 𝑤∈𝑉 𝑝 𝑢𝑤ℎ 𝑤𝑆

𝐿−1

, 𝑢 ∉ 𝑆

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-57-320.jpg)

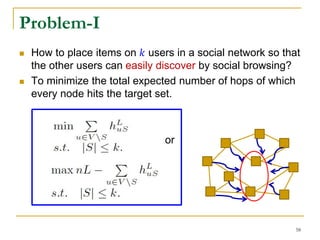

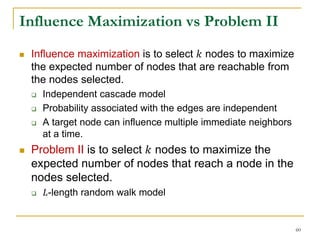

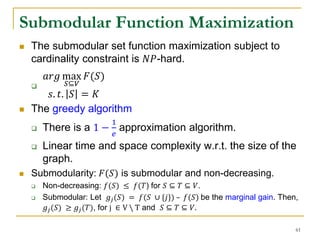

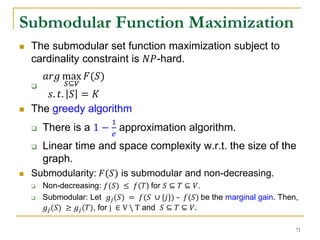

![ The submodular set function maximization subject to

cardinality constraint is 𝑁𝑃-hard.

𝑎𝑟𝑔 max

𝑆⊆𝑉

𝐹(𝑆)

𝑠. 𝑡. 𝑆 = 𝐾

Both Problem I and Problem II use a submodular set

function.

Problem-I: 𝐹1 S = nL − 𝑢∈𝑉𝑆 ℎ 𝑢𝑆

𝐿

Problem-II: 𝐹2(𝑆) = 𝑤∈𝑉 𝔼[𝑋 𝑤𝑆

𝐿

] = 𝑤∈𝑉 𝑝 𝑤𝑆

𝐿

Submodular Function Maximization

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-62-320.jpg)

![Diversified Ranking [Li et al, TKDE’13]

Why diversified ranking?

Information requirements diversity

Query incomplete

PAKDD09-65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-65-320.jpg)

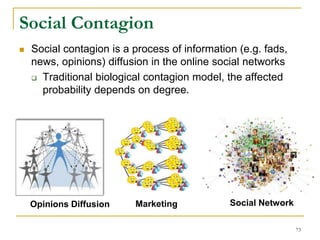

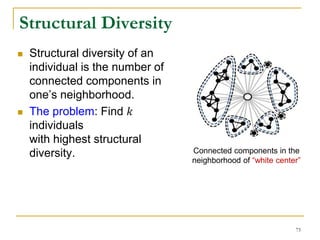

![Facebook Study [Ugander et al., PNAS’12]

Case study: The process of a user joins Facebook in

response to an invitation email from an existing

Facebook user.

Social contagion is not like biological contagion.

74](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-74-320.jpg)

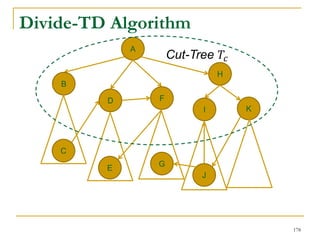

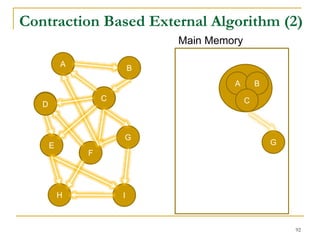

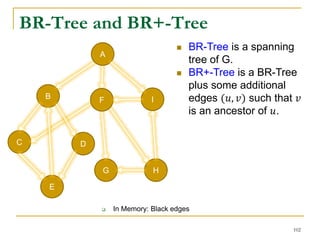

![A

B

D

C

I

E

F

G

H

A

B

C

G

F

Main Memory

Contraction Based External Algorithm (1)

Load in a subgraph and merge SCCs

in it in main memory in every iteration

[Cosgaya-Lozano et al. SEA'09]

91](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-91-320.jpg)

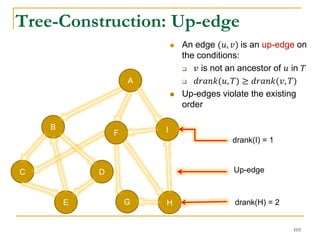

![2

8

3

4

7

5

1

9

6

Tree-Edge

Forward-Cross-Edge

Backward-Edge

Forward-Edge

Backward-Cross-Edgedelete old tree edge

New tree edge

DFS Based Semi-External Algorithm

Find a DFS-tree without

forward-cross-edges

[Sibeyn et al. SPAA’02].

For a forward-cross-

edge (𝑢, 𝑣), delete tree

edge to 𝑣, and (𝑢, 𝑣) as

a new tree edge.

94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-94-320.jpg)

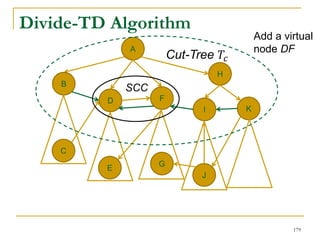

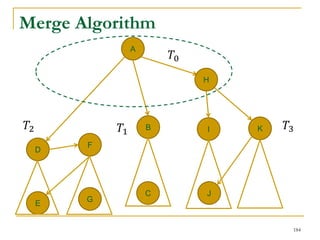

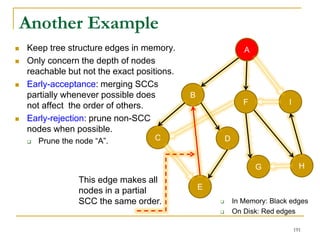

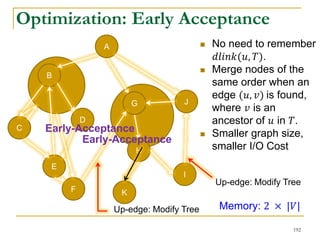

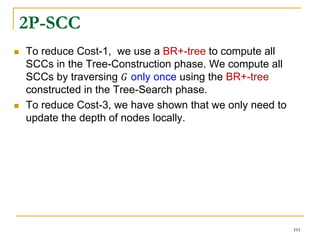

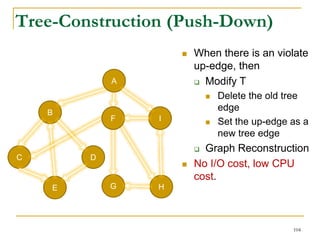

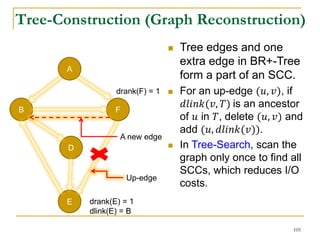

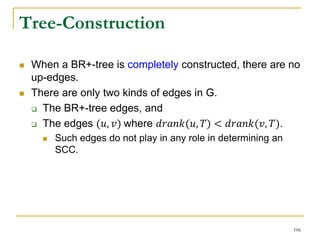

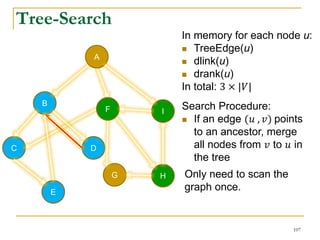

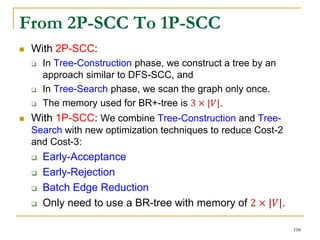

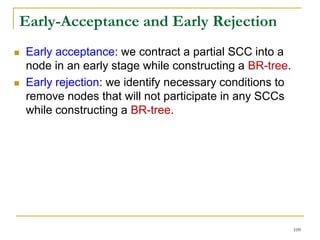

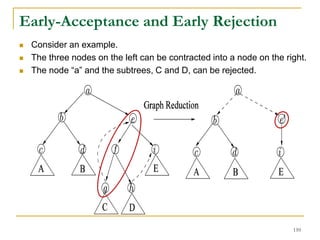

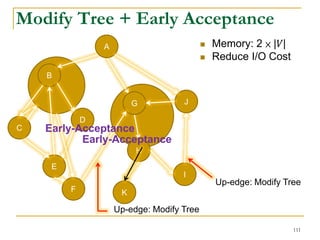

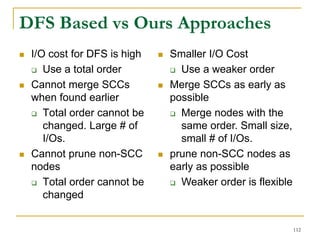

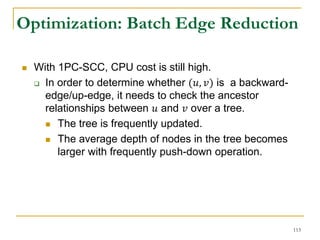

![Our New Approach [SIGMOD’13]

We propose a new two phase algorithm, 2P-SCC:

Tree-Construction and Tree-Search.

In Tree-Construction phase, we construct a tree-like

structure.

In Tree-Search phase, we scan the graph only once.

We further propose a new algorithm, 1P-SCC, to

combine Tree-Construction and Tree-Search with new

optimization techniques, using a tree.

Early-Acceptance

Early-Rejection

Batch Edge Reduction

A joint work by Zhiwei Zhang, Jeffrey Yu, Qin Lu, Lijun Chang, and Xuemin Lin

98](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-98-320.jpg)

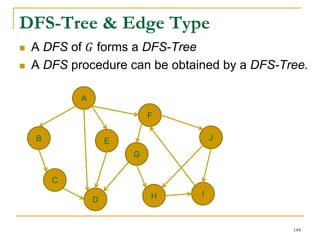

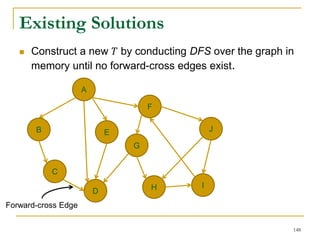

![DFS [SIGMOD’15]

Given a graph 𝐺(𝑉, 𝐸), depth-first search is to

search 𝐺 following the depth-first order.

A

B E

D

C

F

IH

J

G

A joint work by Zhiwei Zhang, Jeffrey Yu, Qin Lu, and Zechao Shang

139](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jeffreyxuyu-largegraphprocessing-160616082809/85/Jeffrey-xu-yu-large-graph-processing-139-320.jpg)