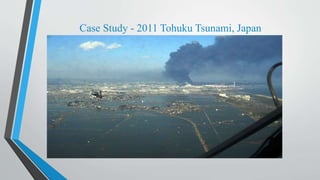

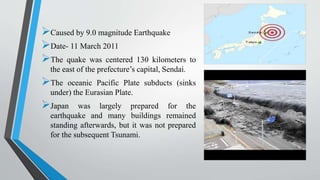

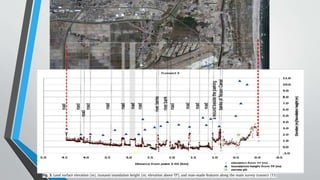

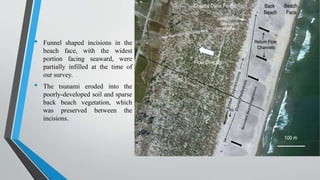

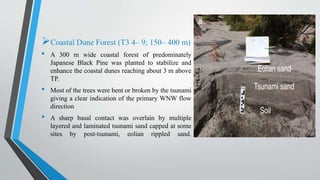

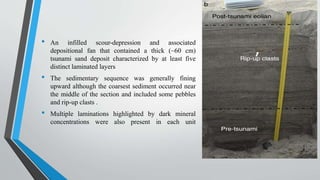

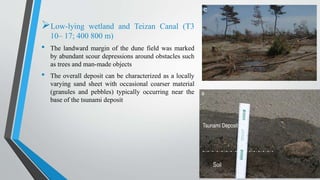

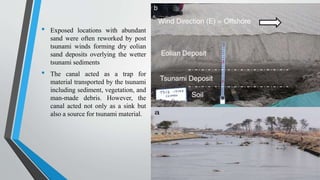

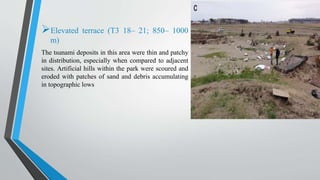

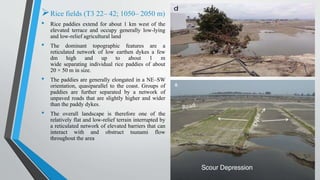

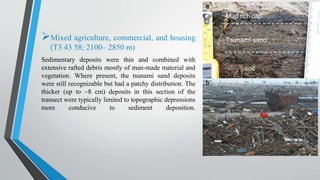

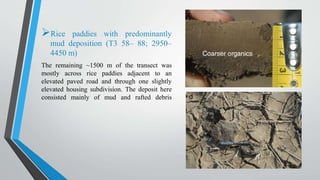

The document summarizes a study of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami in Japan. It describes the tsunami's effects along a 4.5 km transect from the coast inland. Extensive erosion was observed up to 2 km inland. A sheet-like sand deposit was found up to 2.9 km inland, with thickness varying over short distances. The tsunami caused widespread erosion, deposition of sand and mud inland, and landscape changes. Observations along the transect provide insights into tsunami geologic processes and deposits.