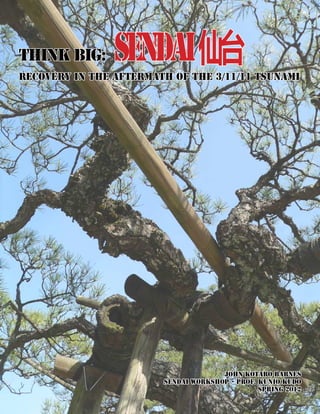

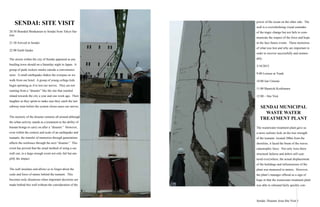

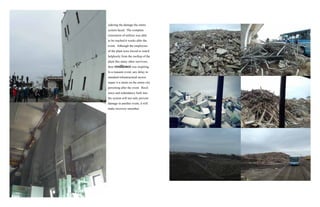

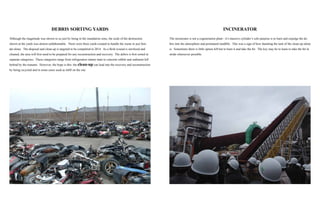

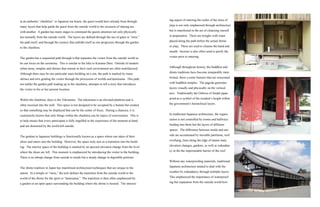

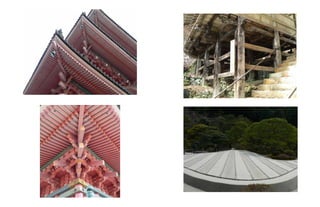

The document summarizes John Barnes' visit to Sendai, Japan to study recovery efforts after the 2011 tsunami. It describes site visits to areas impacted by the tsunami, including the wastewater treatment plant, incinerator, debris sorting yards, an abandoned school, and a park. It then discusses a workshop with architecture students where they brainstormed recovery ideas, including employing spatial layering across the landscape to slow a tsunami rather than using solid walls. The document concludes by discussing how traditional Japanese architecture uses layering and flexible boundaries rather than distinct walls, which could be applied to tsunami recovery.