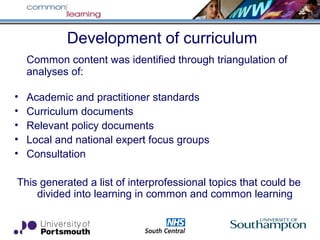

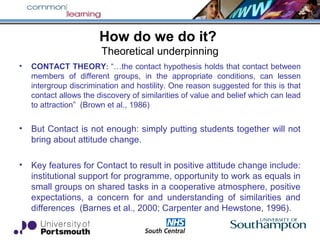

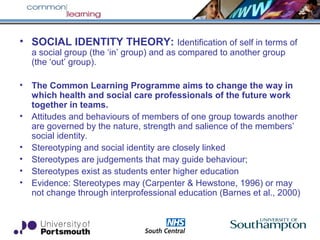

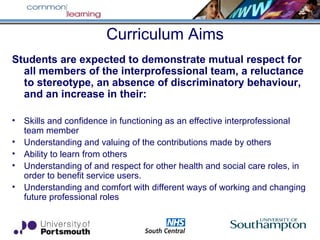

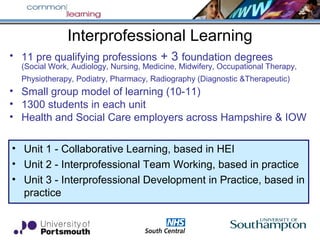

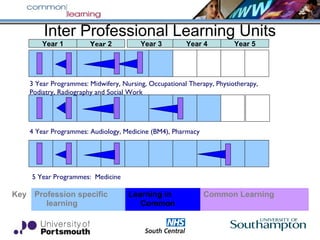

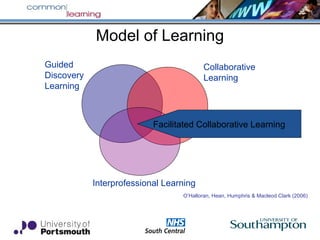

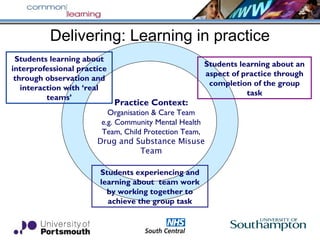

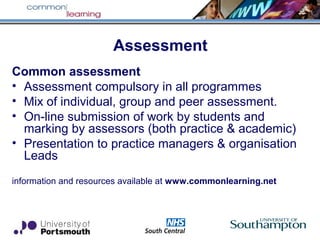

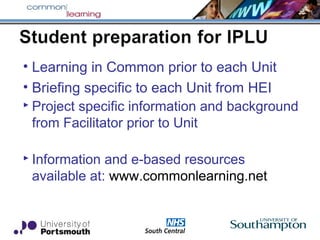

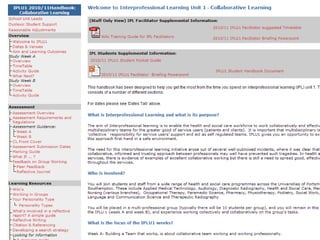

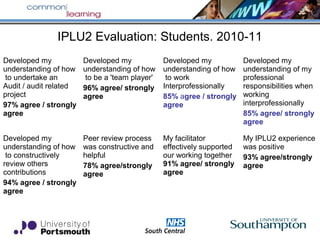

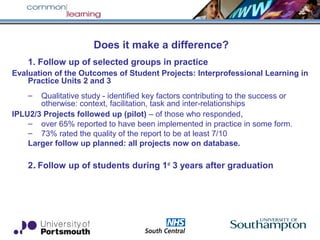

This document describes an interprofessional learning collaboration between universities and the NHS in the UK. It aims to introduce interprofessional education into undergraduate health and social care programs to improve team-based care. Students from 11 professions complete 3 interprofessional learning units that include classroom and practice-based components. They learn in small interprofessional groups, conducting projects on real issues. Evaluation found the experience improved students' understanding of teamwork, roles, and interprofessional practice. Many student projects were subsequently implemented in practice settings. The collaboration aims to develop healthcare graduates prepared to work collaboratively in team-based care models.