1. The document introduces statistics and probability concepts relevant to engineering problems including collecting and analyzing data.

2. Key methods of collecting engineering data are retrospective studies, observational studies, and designed experiments, with advantages and disadvantages of each.

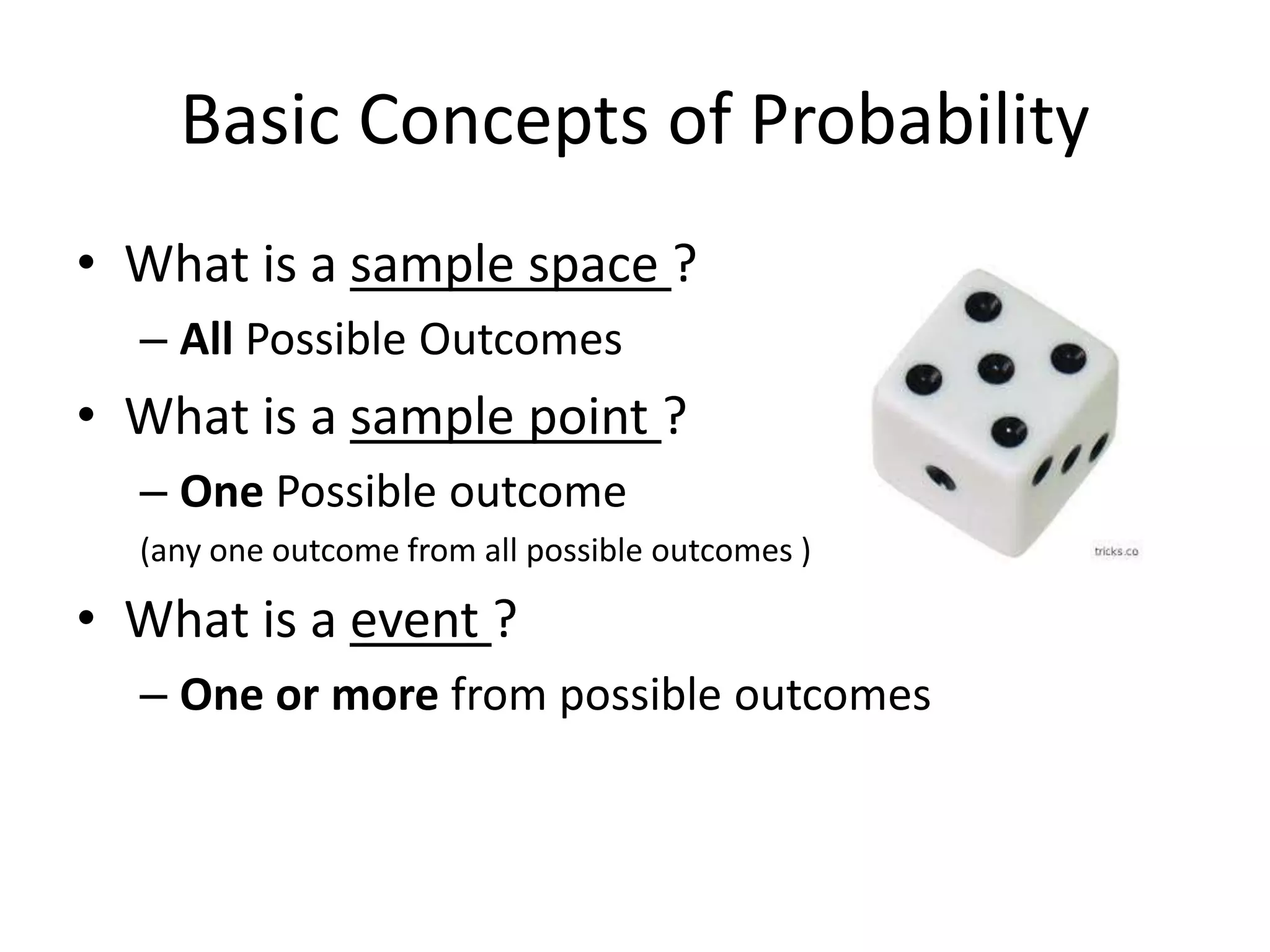

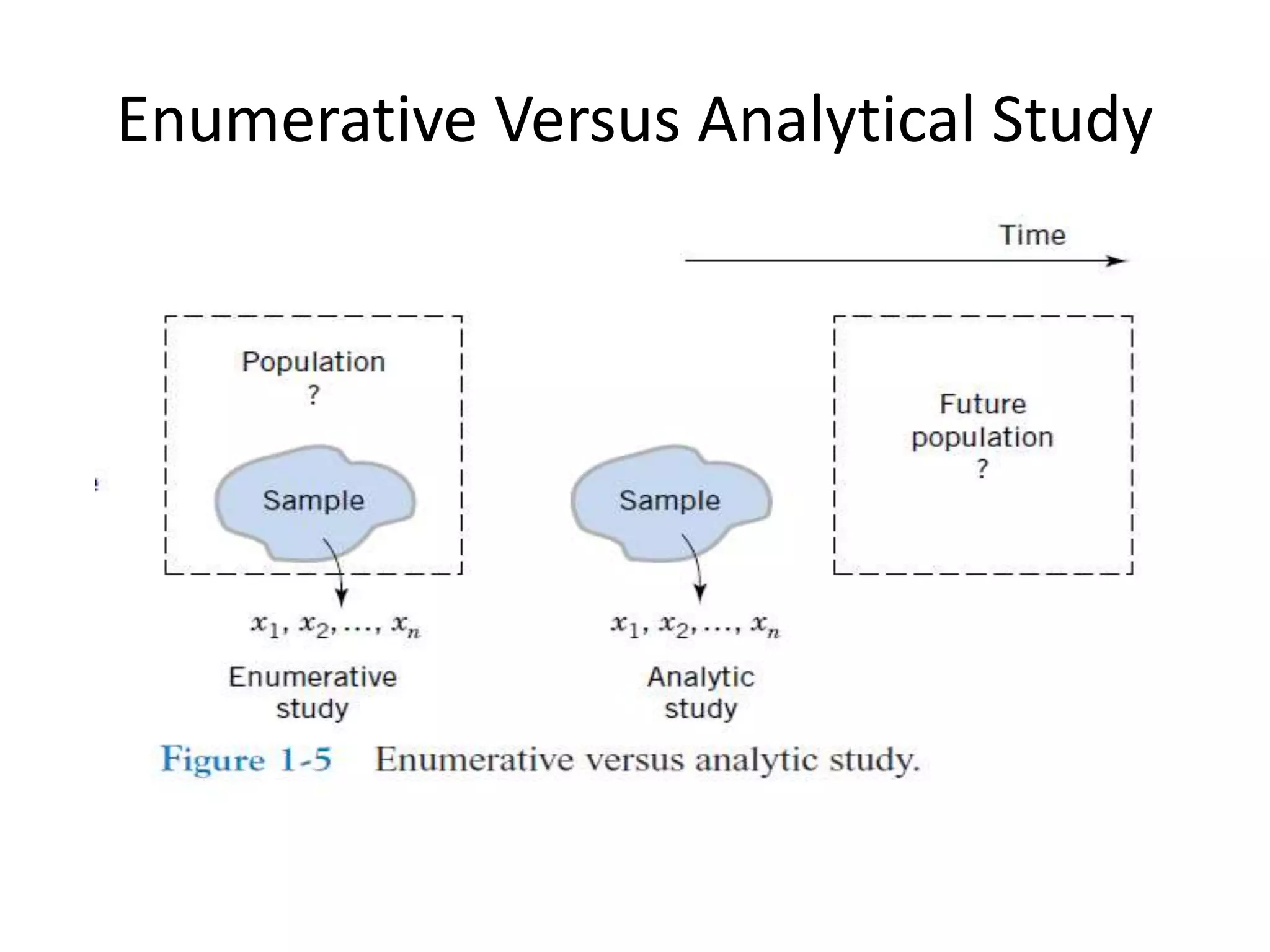

3. Statistical concepts such as populations, samples, variables, and probability are defined and related to engineering applications.

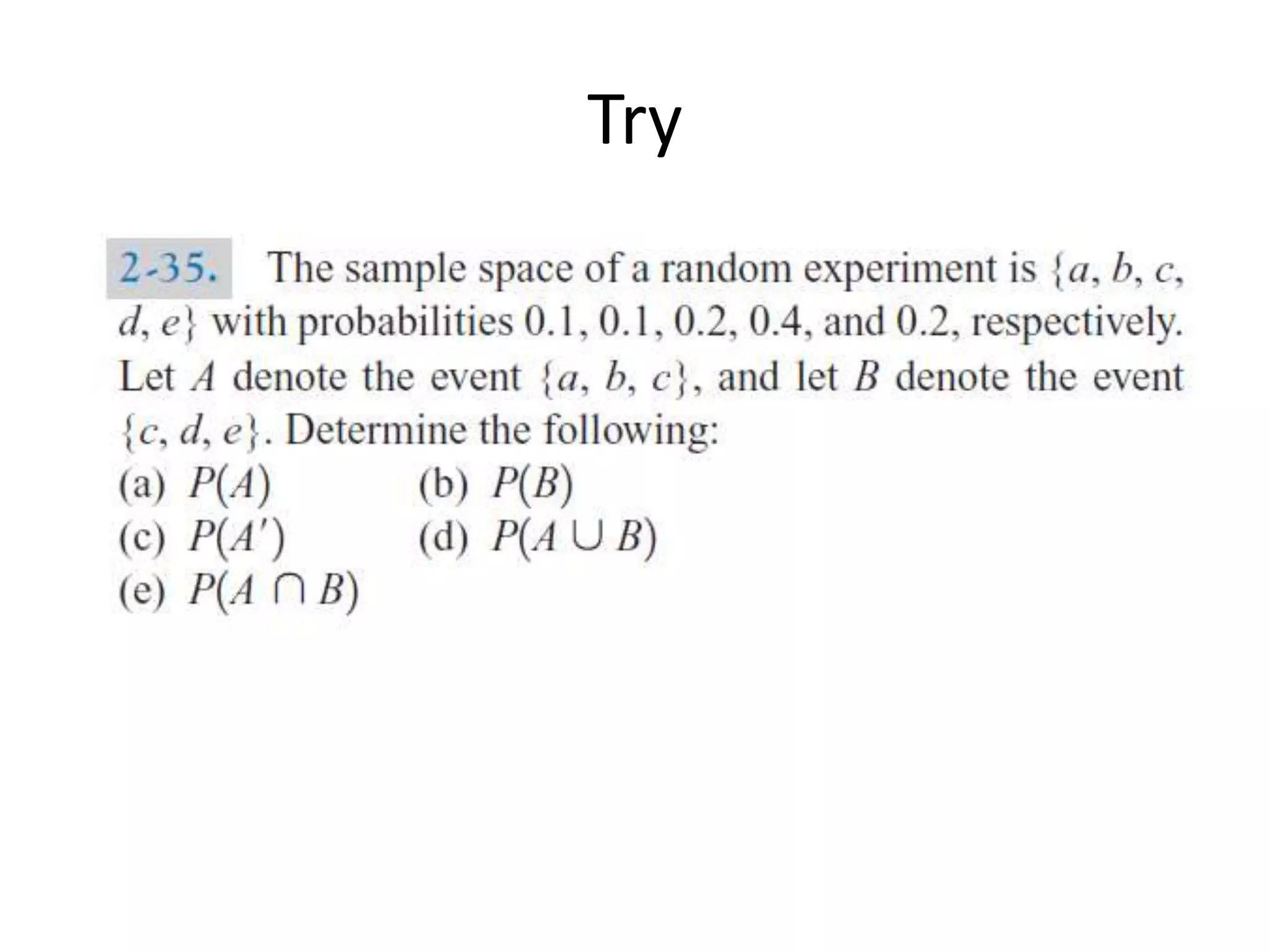

![Grouped Data

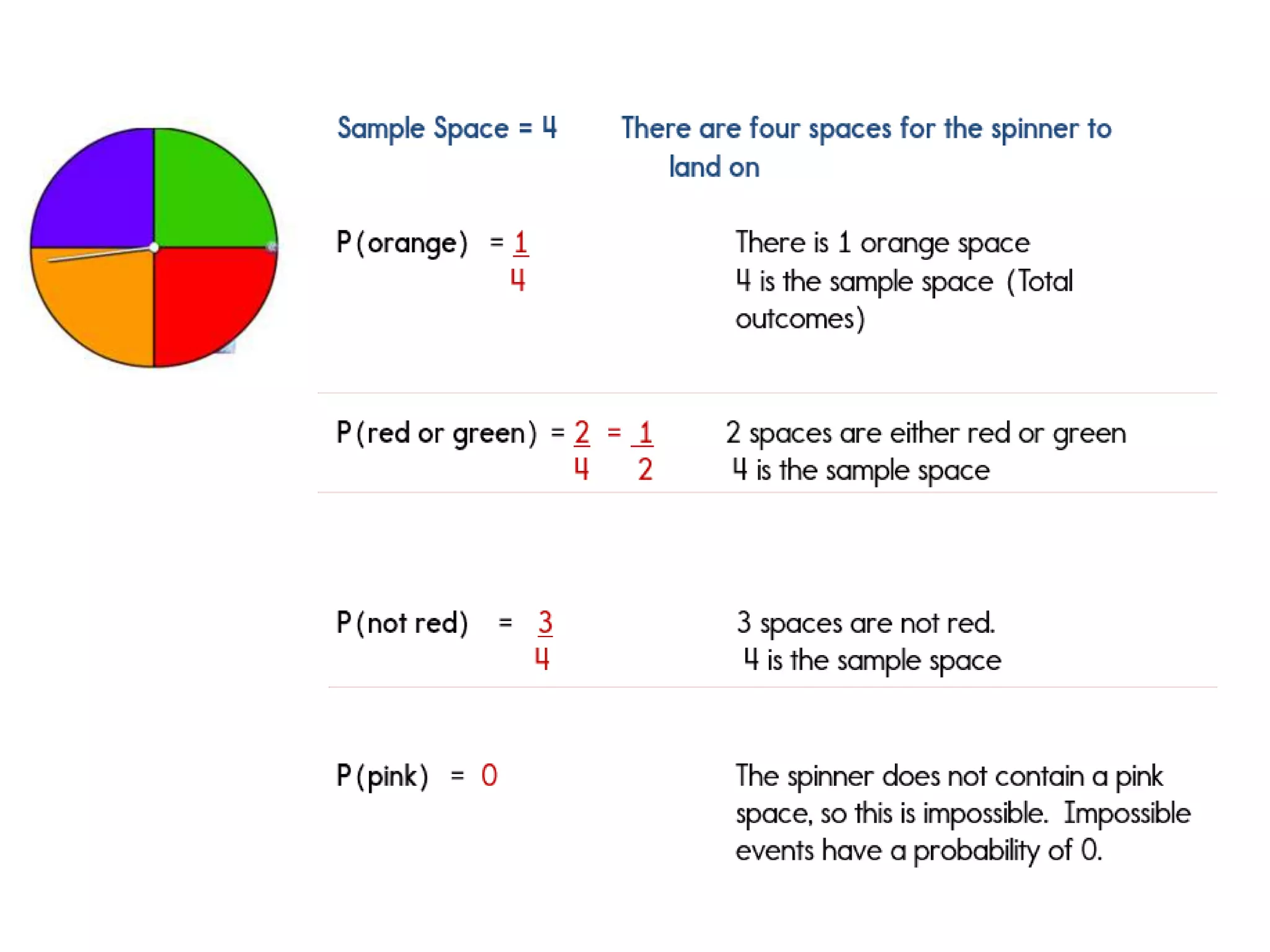

• Data may be available only in a summarized form:

instead of the original value, one may only know

the category or group the value belongs to.

Example,

• Income (per year) by means of groups:

– [(<Rs–20,000), [Rs 20,000–RS 30,000),...,>Rs 100,000];

• If there are many political parties in an election,

those with a low number of voters are often

summarized in a new category “Other Parties”;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit1-200812142932/75/Introduction-to-Statistics-and-Probability-47-2048.jpg)