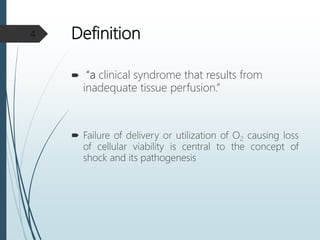

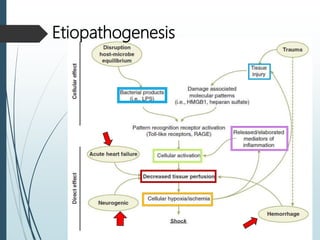

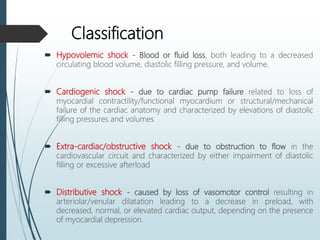

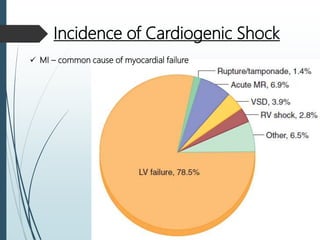

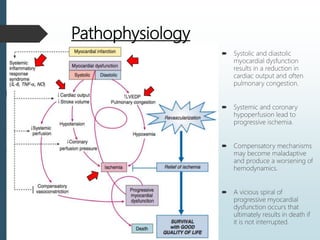

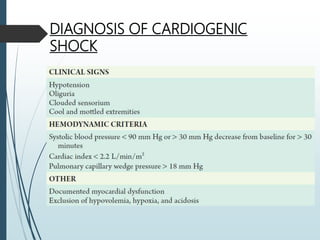

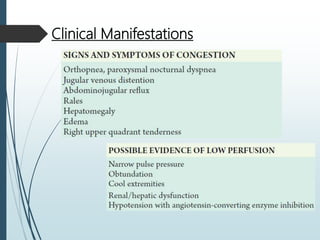

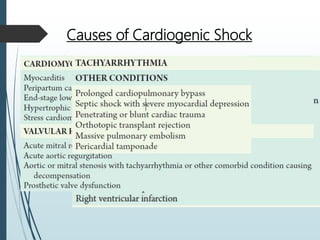

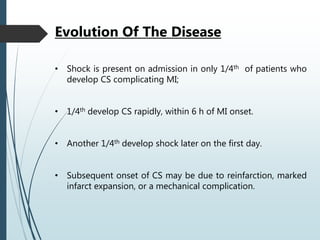

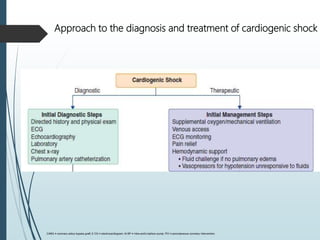

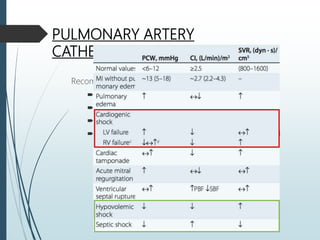

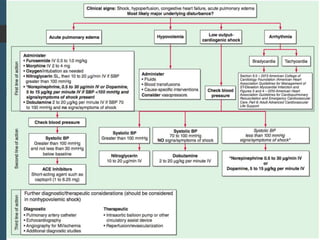

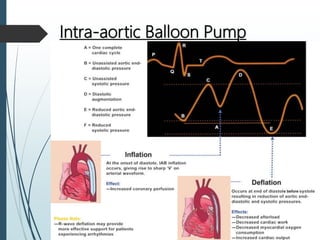

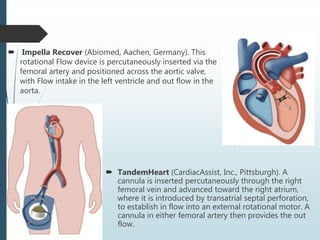

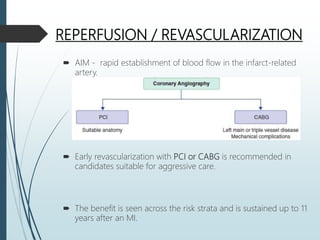

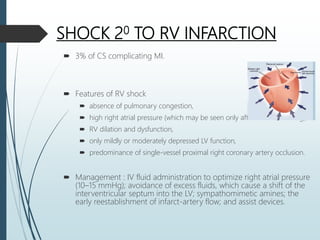

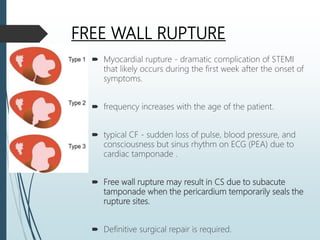

Shock is a clinical syndrome resulting from inadequate tissue perfusion. Cardiogenic shock is a type of shock caused by acute or chronic cardiac dysfunction, with a mortality rate over 50%. It is characterized by reduced cardiac output and systemic/coronary hypoperfusion leading to a vicious cycle of worsening myocardial function. Diagnosis involves assessing clinical manifestations, labs, ECG, echo, and hemodynamics via pulmonary artery catheter. Initial therapy focuses on vasopressors, fluids, and inotropes to support perfusion while evaluating for revascularization if indicated. Mechanical circulatory support may be needed for refractory cases.