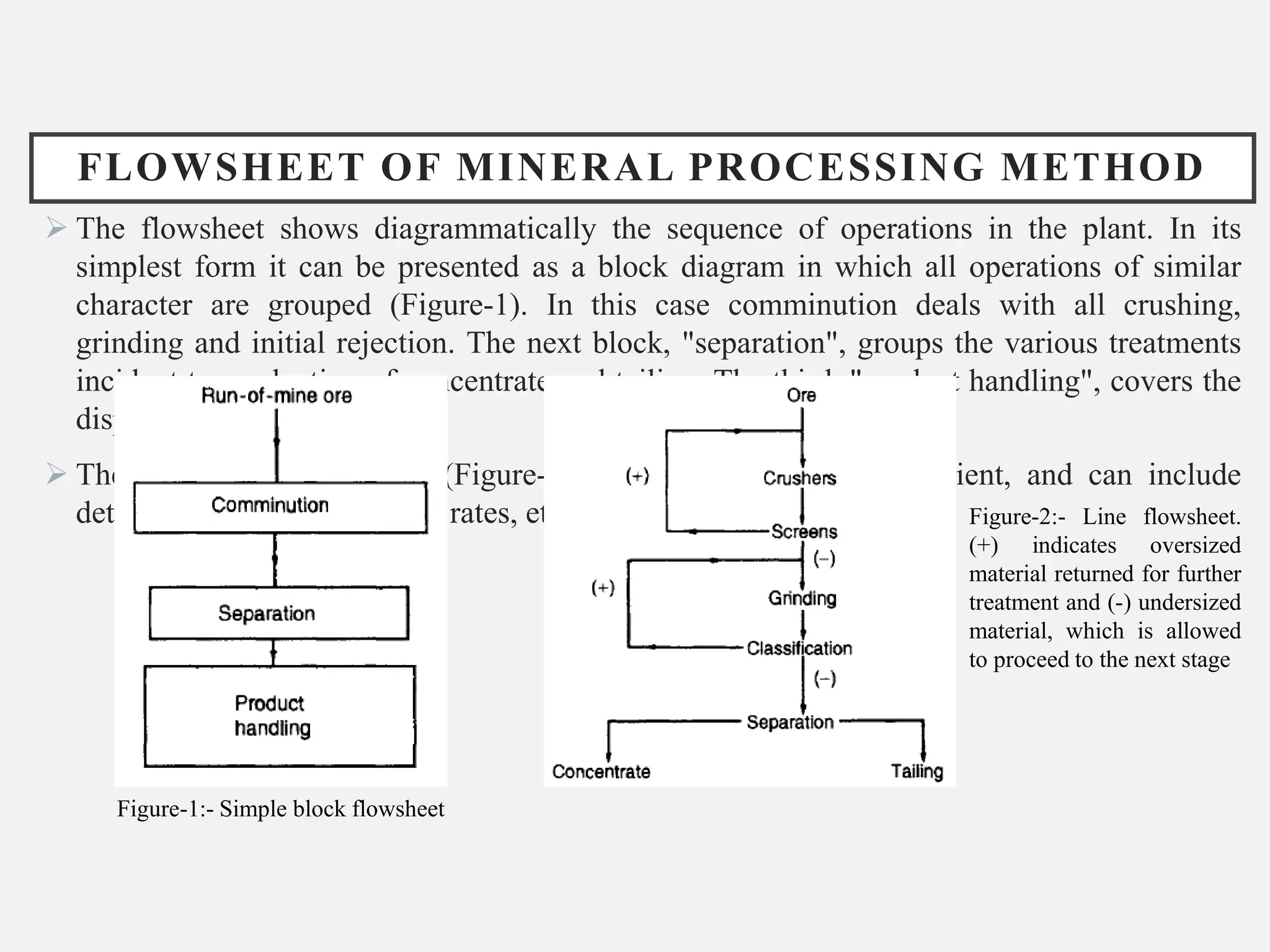

This document provides an introduction to mineral processing. It discusses what minerals are, how they form, and how they are classified. It then describes how ores containing metals are found in nature and how they are concentrated and processed to extract the valuable metals. Physical and chemical processing methods used in mineral concentration are outlined, including crushing, grinding, gravity separation, flotation, magnetic separation, and leaching. The importance of mineral liberation during comminution and the goals of concentration to produce high grade concentrates and tailings are also summarized.