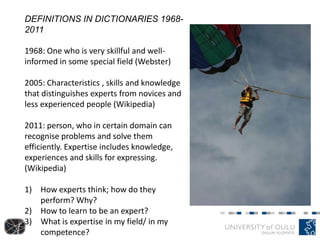

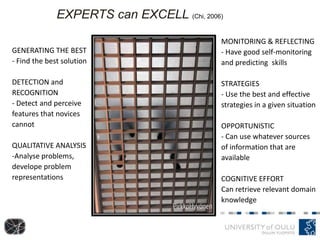

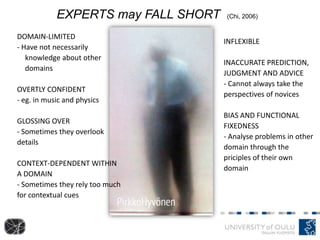

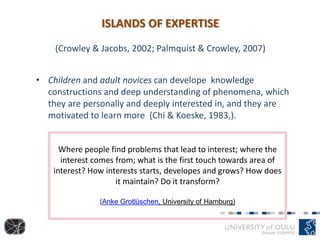

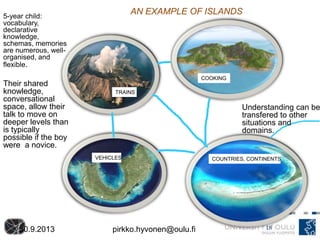

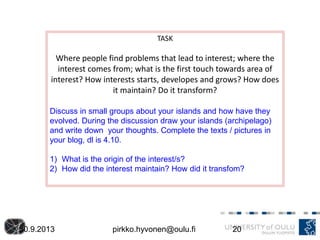

This document discusses expertise and how it is developed. It defines experts as those who are highly skilled and knowledgeable in a specific domain. Experts think differently than novices - they can recognize problems more easily and solve them efficiently. The document discusses how expertise is built through a process of competence development over time, involving the construction of knowledge, expert-like performance, and self-regulation. Novice learners can develop "islands of expertise" in areas they are personally interested in through collaborative learning experiences. True expertise requires extensive experience and practice within a domain.