Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate being studied for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in adults. The INO-VATE ALL study compared inotuzumab ozogamicin to standard chemotherapy for adults with relapsed or refractory ALL. The primary objectives were to demonstrate higher rates of complete remission and longer overall survival with inotuzumab ozogamicin. Complete remission, safety, and overall survival were evaluated. If shown to be effective, inotuzumab ozogamicin could provide a new treatment option for adults with relapsed/refractory ALL.

![B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

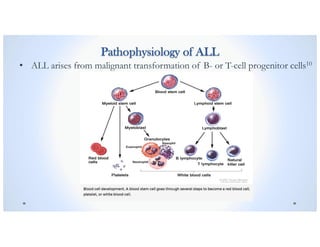

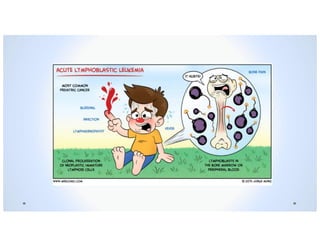

• Acute and Aggressive form of Leukemia (cancer of white blood cells)

• Overproduction and Accumulation of cancerous, immature white

blood cells, known as lymphoblasts1, in the bone marrow

• Lymphoblasts can spread to blood, and infiltrate the lymph nodes,

spleen, liver, central nervous system [CNS], and other organs2

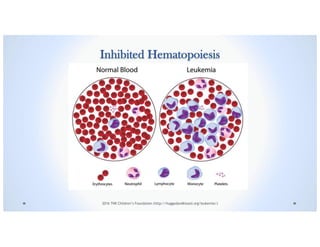

• Reduced production of new, normal-functioning blood cells due to

bone marrow damage and resource depletion by lymphocytes1

• If left untreated within a matter of months11, ALL can be FATAL9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-4-320.jpg)

![Signs & Symptoms

Suppression of Normal Hematopoiesis causes:

o Weakness or Fatigue2

o Anemia (pallor, tachycardia, headache)8

o Fever or Night Sweats2

o Unexpected weight loss or anorexia2

o Pain in the bones or joints2

o Swelling or discomfort in the abdomen2

o Symptoms of an Infection2,8

:

v Shortness of breath

v Chest pain

v Cough

v Vomiting

v Swollen lymph nodes of the neck, armpit, or groin (usually painless)

o Increased risk and frequency of infections (especially bacterial infections like pneumonia due to neutropenia)8

o Thrombocytopenia2

:

v Increased tendency to bruise or bleed easily

Ø Bleeding gums

Ø Purplish patches in the skin

Ø Petechiae [flat, pinpoint spots under the skin]

Doctors Health Press

Consumer Health Digest](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-10-320.jpg)

![Rationale of the Study

• While many potential treatments have been studied, only a limited number of

medicines for relapsed or refractory adults with ALL have been approved by the

FDA and other regulatory authorities in the past decade.

• The current standard treatment is intensive, lengthy chemotherapy with the goal

of halting the signs and symptoms of ALL (called hematologic remission) and

becoming eligible for a stem-cell transplant.11

• Allogeneic Stem-Cell Transplantation [SCT] is the main goal after salvage

treatment because it is the ONLY potentially curative treatment option for adults

with relapsed or refractory ALL.1

• A previous phase 2 study of Inotuzumab Ozogamcin, administered on either a

weekly or a monthly schedule, for the treatment of patients with relapsed or

refractory B-cell ALL showed antitumor activity.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-18-320.jpg)

![Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation [SCT]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-19-320.jpg)

![Current Standard Chemotherapy Regimens

Complete Remission [CR] Rates1:

o Adults with Newly diagnosed B-cell ALL: 60 to 90 %

o However many patients relapse, and ONLY approximately 30 to 50% will have a disease-free

survival lasting 3 years or longer.

o Adults with Relapsed or Refractory ALL: 31 to 44% (if 1st salvage therapy)

18 to 25% (if 2nd salvage therapy)

o Complete Remission [CR] is typically a prerequisite for subsequent allogeneic stem-cell

transplantation, the low rates of complete remission associated with current chemotherapy regimens

mean that few adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL, 5 to 30% proceed to transplantation.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-20-320.jpg)

![Intent of the Study

• To assess the clinical activity and safety of single-agent Inotuzumab Ozogamicin, as

compared with standard intensive chemotherapy, when it is administered as the first

or second salvage treatment in adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL.1

• 1st Primary Objective:

o To show significantly higher rates of Complete Remission [CR] or Complete Remission

with Incomplete Hematologic Recovery [Cri] in the Inotozumab Ozogamacin group than

in the Standard-therapy group. 1

• 2nd Primary Objective:

o To show significantly longer Overall Survival in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in

the Standard-therapy group, at a pre-specified boundary of P=0.0208.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-21-320.jpg)

![Monitoring Parameters

Primary End Points1:

1. Complete Remission [CR]: The disappearance of leukemia as indicated by < 5% marrow blasts

and the absence of peripheral blasts, with recovery of hematopoiesis defined by ANC ≥ 1,000

cells/µL and platelets ≥ 100,000 cells/µL.1 C1 extramedullary disease status is required1; patients

were considered to have C1 extramedullary disease status if the following criteria were met:

q Complete disappearance of all measurable and non-measurable extramedullary disease with the

exception of lesions for which the following must be true: for patients with at least one measurable

lesion, all nodal masses > 1.5 cm in greatest transverse diameter (GTD) at baseline must have

regressed to ≤ 1.5 cm in GTD and all nodal masses ≥ 1 cm and ≤ 1.5 cm in GTD at baseline must

have regressed to < 1 cm GTD or they must have reduced by 75% in sum of products of greatest

diameters (SPD).1

q No new lesions.1

q Spleen and other previously enlarged organs must have regressed in size and must not be palpable.1

q All disease must be assessed using the same technique as at baseline.1

2. Complete Remission with Incomplete Hematologic Recovery (CRi): Complete Remission

[CR] except with ANC < 1,000 cells/µL and/or platelets < 100,000 cells/µL.1

3. Overall Survival: Time from randomization to death due to any cause, censored at the last

known alive date.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-22-320.jpg)

![Monitoring Parameters

Secondary End Points1:

1. Safety Measures

2. Duration of Remission: Time from remission to progressive disease (objective progression,

relapse, treatment discontinuation due to health deterioration) or death.1

3. Progression-Free Survival: Time from randomization to the earliest of disease progression

(including objective progression, relapse from [CR/CRi], treatment discontinuation doe to global

deterioration of health status), starting new induction therapy or poststudy [SCT] without

achieving [CR/CRi], or death due to any cause, censored at the last valid disease assessment.1

4. Rate of Subsequent Stem-Cell Transplantation [SCT]1

5. Percentage of Patients, who achieved [CR], who had results below the threshold for

minimal residual disease specified as 0.01% bone marrow blasts](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-23-320.jpg)

![Measurement Tools

1. Complete Blood Count (CBC): A full blood count test to measure the levels of

white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets, which was needed and relied on to

calculate ANC and evaluate Complete Remission [CR].

2. Multicolor, Multi-parameter Flow Cytometry: The threshold for minimal residual

disease was specified as 0.01% bone marrow blasts and was assessed at a central

laboratory.

3. Bone Marrow Aspiration (or Bone Marrow Biopsy, if clinically indicated):

Performed for all patients with a disease assessment at screening, between Days 16

and 28 of Cycles 1, 2, and 3, and every 1 to 2 cycles thereafter; at the end-of-treatment

visit; during planned follow-up visits; and as clinically indicated.

4. Karyotype was assessed at a local laboratory.

5. Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph) positivity was assessed at a central or local

laboratory or through medical history.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-25-320.jpg)

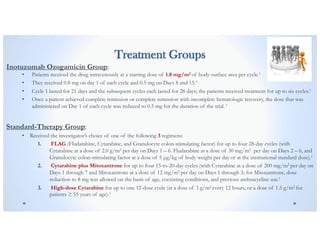

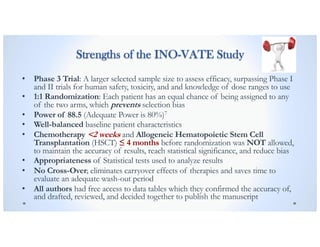

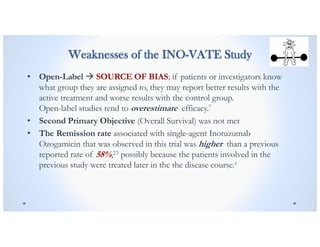

![INO-VATE Study Design and Methods

• Open-label (no blinding)

• Two-Arm/Group (326 patients underwent randomization,

only the first 219 [109 om each group] were included in the

primary intention-to-treat analysis of complete remission)

• 1:1 Randomization of Patients

• Phase 3 trial

• No Cross-Over was allowed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-26-320.jpg)

![Eligibility/Inclusion Criteria

Patients must be/have:

• B- cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL):

ü Relapsed or Refractory (≥ 5% bone marrow blasts on local morphologic analysis) AND

ü CD22-positive AND

ü Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) positive or negative

• Sex: Males and Females

• Age ≥ 18 years or older

• Scheduled to receive their 1st or 2nd Salvage treatment

• Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (except Burkitt Lymphoma)

• Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status: ≤ 2

• Adequate Hepatic Function:

ü Total Serum Bilirubin ≤ 1.5 x Upper Limit of Normal [ULN] (except for documented

Gilbert Syndrome: ≤ 2 x ULN for hepatic abnormalities considered tumor-related)

ü Alanine Aminotransferase [ALT] and Aspartate Aminotransferase [AST]: ≤ 2.5 x ULN

ü Serum Creatinine [SCr] ≤ 2.5 x ULN OR Creatinine Clearance [CrCl] ≥ 40 mL/min

associated with ANY Serum Creatinine [SCr] level](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-27-320.jpg)

![Exclusion Criteria

• Patients with:

o Peripheral Absolute Lymphoblast Count ≥ 10,000 cells/µL *Treatment to reduce circulating blasts

was allowed within 2 weeks of randomization with Hydroxyurea AND/OR Steroids/Vincristine

o Burkitt Lymphoma

o Isolated Testicular or CNS Extramedullary relapse

• Treatments NOT Allowed:

o Chemotherapy < 2 weeks before randomization *EXCEPT to reduce circulating lymphoblast count

or palliation [Steroids, Hydroxycarbamide, or Vincristine]

o Monoclonal Antibody treatment < 6 weeks before randomization (for Rituximab: ≥ 2 weeks before

randomization)

o Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) ≤ 4 months before randomization](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-29-320.jpg)

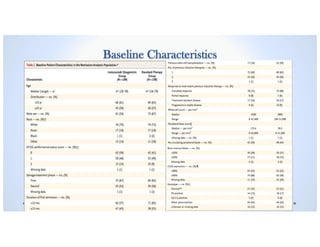

![Statistical Analysis

• With a sample size of 218 patients and a one-sided alpha level of P<0.0125,

the study had 88.5% power to detect a difference in the rate of Complete

Remission [CR] (including Complete Remission with Incomplete Hematologic

Recovery [CRi]) of 24 percentage points between the two groups (61% in the

Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group vs. 37% in the standard-therapy group).

• What is power?

o The ability of a study to detect a significant difference between treatment groups;

the probability that a study will have a statistically significant result (P<0.05).7

o By convention, adequate study power is usually set at 0.8 (80%).

o Power increases as sample size increases.7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-33-320.jpg)

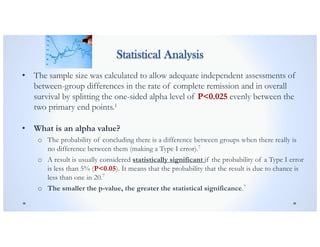

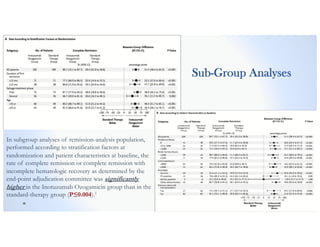

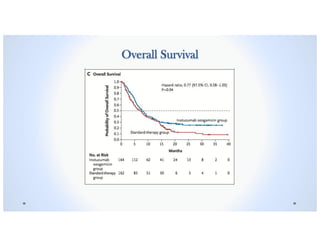

![Primary Results

• 1st Primary Objective: The rate of Complete Remission [CR] or Complete Remission

with Incomplete Hematologic Recovery [CRi] was significantly higher in the

Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in the Standard-therapy group (80.7% [95%

confidence interval {CI}, 72.1 to 87.8] vs. 29.4% [95% CI: 21.0 to 38.8], P<0.001).1

• 2nd Primary Objective: The median Overall Survival was 7.7 months (95% CI, 6.0 to

9.2) in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group vs. 6.7 months (95% CI, 4.9 to 8.3) in the

Standard-therapy group, P=0.04.1 ß 2nd OBJECTIVE NOT MET!

o A predetermined boundary of P=0.0208 was set to show significantly longer overall

survival in the Inzotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in the Standard-therapy group.

• The rate of 2-year Overall Survival was 23% (95% CI, 16 to 30) in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group vs. 10% (95% CI, 5 to 16) in the Standard-therapy group.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-37-320.jpg)

![Exploratory Post Hoc Analysis

• Data for Overall Survival appeared to depart from the proportional-hazards

assumption as reflected by an apparent heterogeneity in the curve for standard

therapy; therefore an exploratory post hoc analysis of restricted mean survival

time was applied (truncation time, 37.7 months) to alternatively define the

clinical benefit of Inotuzumab Ozogamicin.1

• In this analysis, mean Overall Survival was longer in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group than in the Standard-therapy group (mean [±], 13.9±1.10

months vs. 9.9±0.85 months, P=0.005).1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-39-320.jpg)

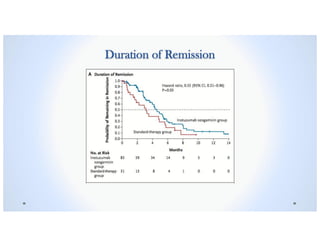

![Secondary Results

• Among the patients who achieved [CR] or {CRi], the percentage who had bone marrow

blast results below the 0.01% threshold for minimal residual disease was significantly

higher than in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in the Standard-therapy group

(78.4% [95% CI, 68.4 to 86.5] vs. 28.1% [95% CI, 13.7 to 46.7], P<0.001.1

• Significantly more patients proceeded to stem-cell transplantation directly after treatment

in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in the Standard-therapy group (41% [45 of 109

patients] vs. 11% [12 of 109 patients], P<0.001.1

• The Duration of Remission was longer in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group than in the

Standard-therapy group. The median duration of remission was 4.6 months (95% CI, 3.9

to 5.4) in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group vs. 3.1 months (95% CI, 1.4 to 4.9) in the

Standard-therapy group, P<0.03.1

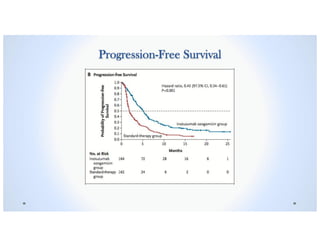

• Progression-free Survival was significantly longer in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group

than in the Standard-therapy group (median, 5.0 months [95% CI, 3.7 to 5.6] vs. 1.8

months [95% CI, 1.5 to 2.2], P<0.001.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-40-320.jpg)

![Serious Adverse Events

The percentage of patients who had

serious adverse events was similar in

the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group

and the Standard-therapy group

(48% and 46%, respectively).1

Febrile Neutropenia was the most

frequently reported serious adverse

event in both treatment groups.1

In both treatment groups, the most

common hematologic adverse event

of any cause were cytopenias.1

Liver-related adverse events were

more common in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group than the

Standard-therapy group.1

Veno-occlusive disease occurred

more frequently in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group than in the

Standard-therapy group (11% [15

patients] vs. 1% [1 patient]).1

In the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin

The most frequent liver-related

adverse events of any grade that

occurred during treatment were an

Increased Aspartate

Aminotransferase level (in 20% of

patients in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group and 10% of

patients in the Standard-therapy

group), Hyperbilirubinemia (in 15%

and 10%, respectively), and

increased Alanine

Aminotransferase level (in 14% and

11% respectively.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-43-320.jpg)

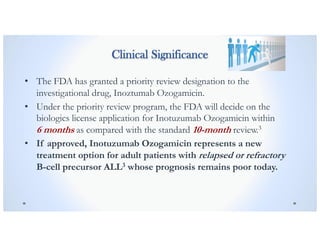

![Conclusions

• The rate of complete remission was significantly higher in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group was

than in the Standard Intensive Chemotherapy with adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL.1

• Among patients who had Complete Remission [CR], the percentage who had bone marrow blast

results below the threshold for minimal residual disease was 2.8 times as high in the Inotuzumab

Ozogamicin group as in the Standard-therapy group (P<0.001).1

• More patients in the Inotuzumab Ozogamicin group proceeded to Stem-cell Transplantation after

treatment than after Standard-therapy treatment (41% vs. 11%, P<0.001).1

• Both Progression-Free and Overall Survival were longer with Inotuzumab Ozogamicin.1

• Veno-occlusive liver disease was a major adverse event associated with Inotuzumab Ozogamicin.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-47-320.jpg)

![References

1. Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 740-53/ DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509277

2. PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment. Bethesda, MD:

National Cancer Institute. Updated <03/16/2017>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/hp/adult-all-

treatment-pdq. Accessed <05/19/2017>. [PMID: 26389171]

3. Inman, S. (2017, February 21). FDA Grants Inotuzumab Ozogamicin Priority Review for ALL. Retrieved May 19, 2017,

from http://www.onclive.com/web-exclusives/fda-grants-inotuzumab-ozogamicin-priority-review-for-all

4. Jabbour, E., Kantagrjian, H. & Cortes,J. (2015). Use of second and third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the

treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: An evolving treatment paradigm. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, 15(6),

323-334. DOI: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.03.006

5. Prinja, S., Gupta, N. & Verma, R. (2010), Censoring in clinical trials: Review of survival analysis techniques. Indian Journal

of Community Medicine, 35(2), 217. DOI: 10.4103/0970-0218.66859

6. Malone PM, Kier KL, Stanovich JE, Malone MJ. Drug Information: A Guide for Pharmacists. 5th Edition. New York,

NY: McGraw-Hill, 2014. ISBN: 9780071804349 (available in AccessPharmacy via St. John’s University Libraries)

7. Allen, Jill. (2005). Applying Study Results to Patient Care: Glossary of Study Design and Statistical Terms. Pharmacist’s

Latter/Prescriber’s Letter. Volume 21 – Number 210610

8. Seiter, K (2014, February 5). Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F; Sacher, RA; Besa, EC, eds. "Acute Lymphoblastic

Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

9. American Cancer Society. Leukemia – Acute Lymphocytic (Adults). Available at:

http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003109-pdf.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2017.

10. Pui CH, Jeha S: New therapeutic strategies for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6

(2): 149-65, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inotuzumabozogamicin-190726081558/85/Inotuzumab-ozogamicin-BESPONSA-48-320.jpg)