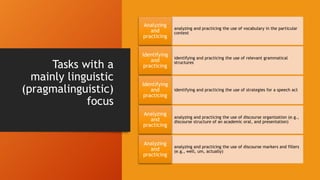

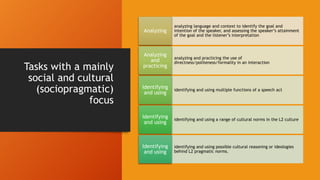

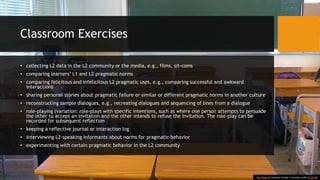

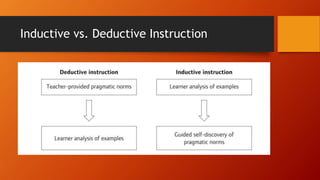

The document discusses teaching pragmatics, which aims to help language learners understand socially appropriate language use. Pragmatics is often overlooked in language education. Explicit teaching of pragmatics through analyzing language examples and contexts is generally more effective than implicit teaching. Various frameworks can inform pragmatics instruction, including noticing hypothesis, output hypothesis, interaction hypothesis, and sociocultural theory. Teachers can use tasks focusing on linguistic or sociocultural aspects to raise pragmatic awareness. Both inductive and deductive approaches show promise, though inductive instruction may lead to longer-lasting pragmatic knowledge.