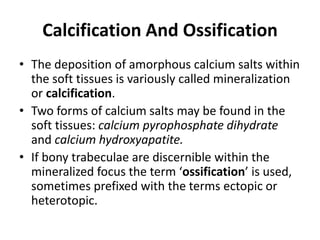

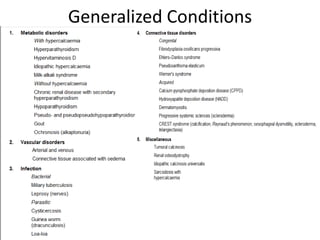

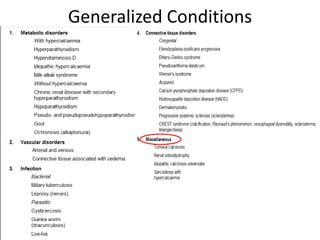

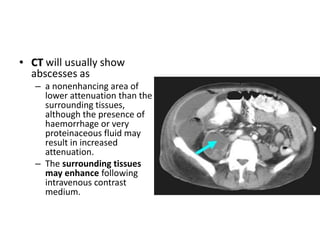

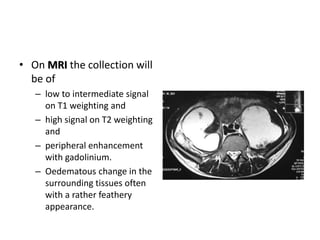

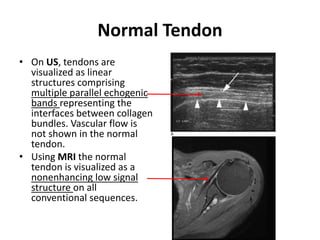

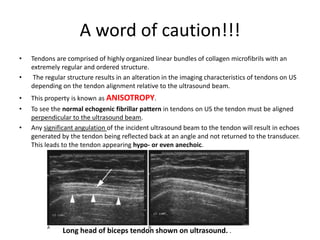

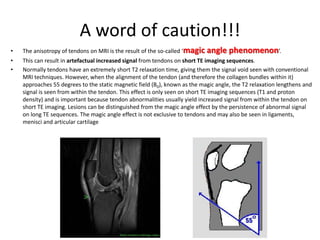

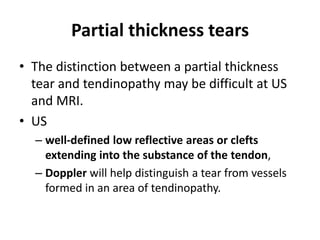

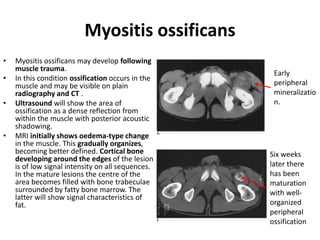

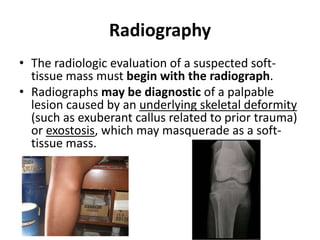

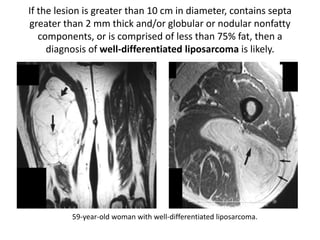

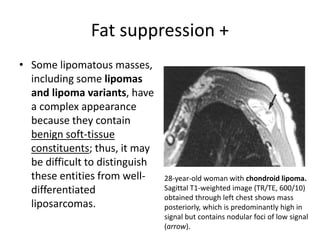

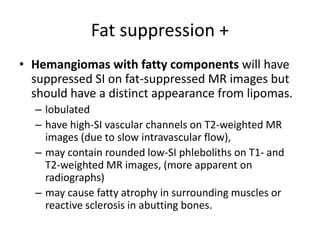

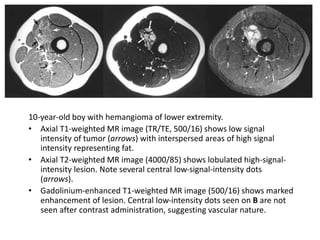

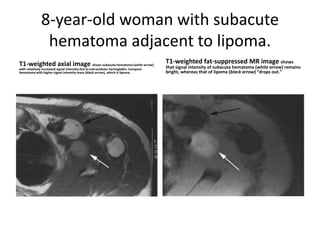

This document provides an overview of imaging techniques for evaluating soft tissues, including radiography, ultrasound, CT, MRI, and radionuclide imaging. It discusses the advantages and limitations of each technique. It also reviews common radiographic observations of soft tissue abnormalities like calcification, ossification, and conditions that cause generalized soft tissue changes such as metabolic disorders, infections, and congenital disorders. The level of detail provided is intended to help radiologists and clinicians understand the diagnostic potential and appropriate clinical application of various imaging modalities for soft tissue evaluation.

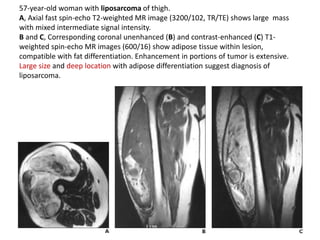

![Radionuclide imaging

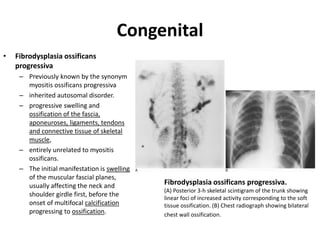

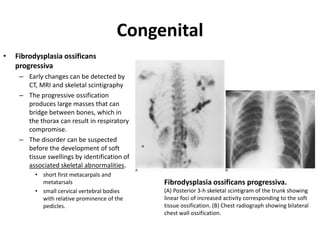

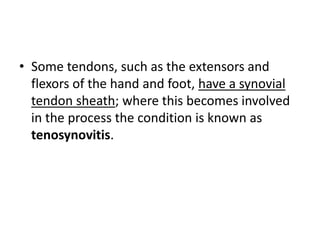

• Numerous soft tissue lesions concentrate bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals. Any soft tissue

abnormality with the propensity to develop mineralization can show ectopic activity on

skeletal scintigraphy. These include congenital abnormalities such as fibrodysplasia ossificans

progressiva , collagen vascular disorders such as dermatomyositis, trauma as in myositis

ossificans and neoplasia as in extraskeletal osteosarcoma and synovial sarcoma.

• Skeletal scintigraphy may be helpful in assessing the maturity of ectopic ossification as can

be seen with spinal cord injuries. In this situation surgical resection is best deferred until the

ossification becomes stable to minimize the risk of recurrence.

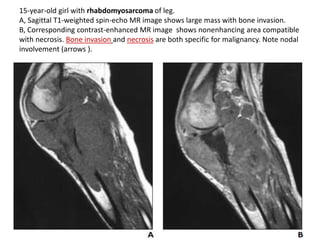

• Scintigraphy is not routinely indicated in the surgical staging of soft tissue sarcomas. Local

osseous extension is uncommon and is best demonstrated by MRI. Bone metastases from

soft tissue sarcomas are rare in the absence of disseminated disease elsewhere, notably the

lungs, but can be seen in alveolar soft part sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.

• Positron emission tomography (PET) with [F-18] fluorodeoxyglucose has not yet been widely

studied for soft tissue lesions; it can be used to assess soft tissue tumour metabolism in order

to grade tumours and to assess relapse. It may also be helpful in assessing malignant

transformation of peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/softtissuepathology-141003075154-phpapp01/85/Imaging-of-Soft-tissue-pathology-16-320.jpg)