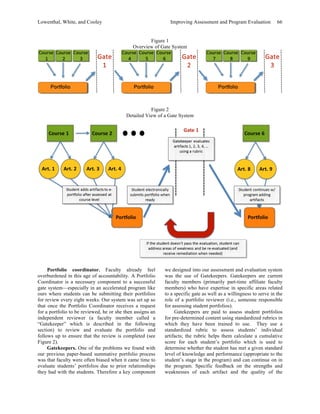

The paper discusses the implementation of electronic portfolios (eportfolios) in a teacher education program to improve student assessment and program evaluation, responding to increasing accountability demands in higher education. It highlights the shortcomings of traditional summative paper-based portfolios and the need for a redesigned assessment system that tracks student learning throughout the program. The authors share their experiences and offer insights into the benefits and challenges of eportfolios, emphasizing their potential role in enhancing educational outcomes and program accreditation.