The document discusses several key aspects of language and linguistics, including:

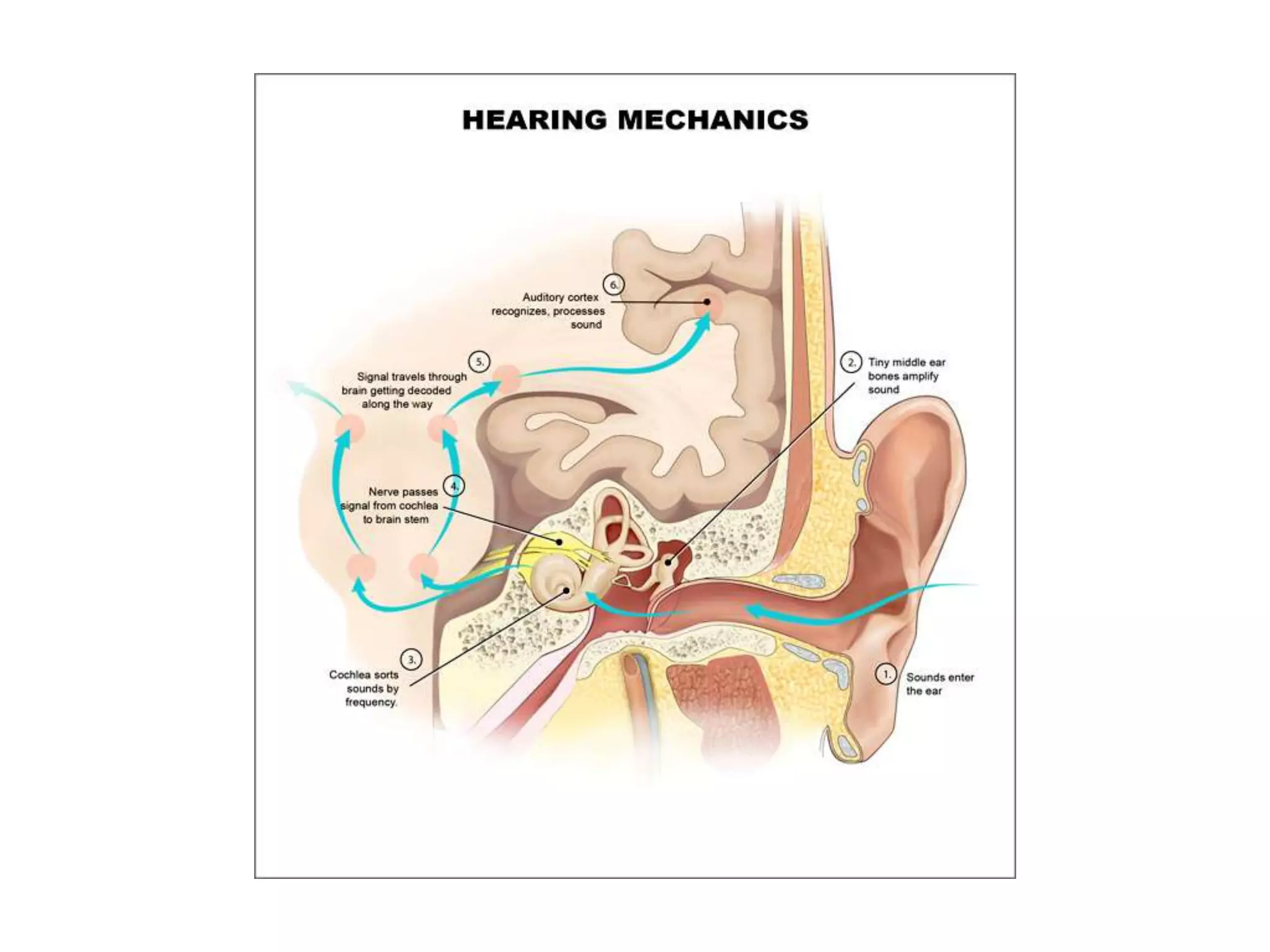

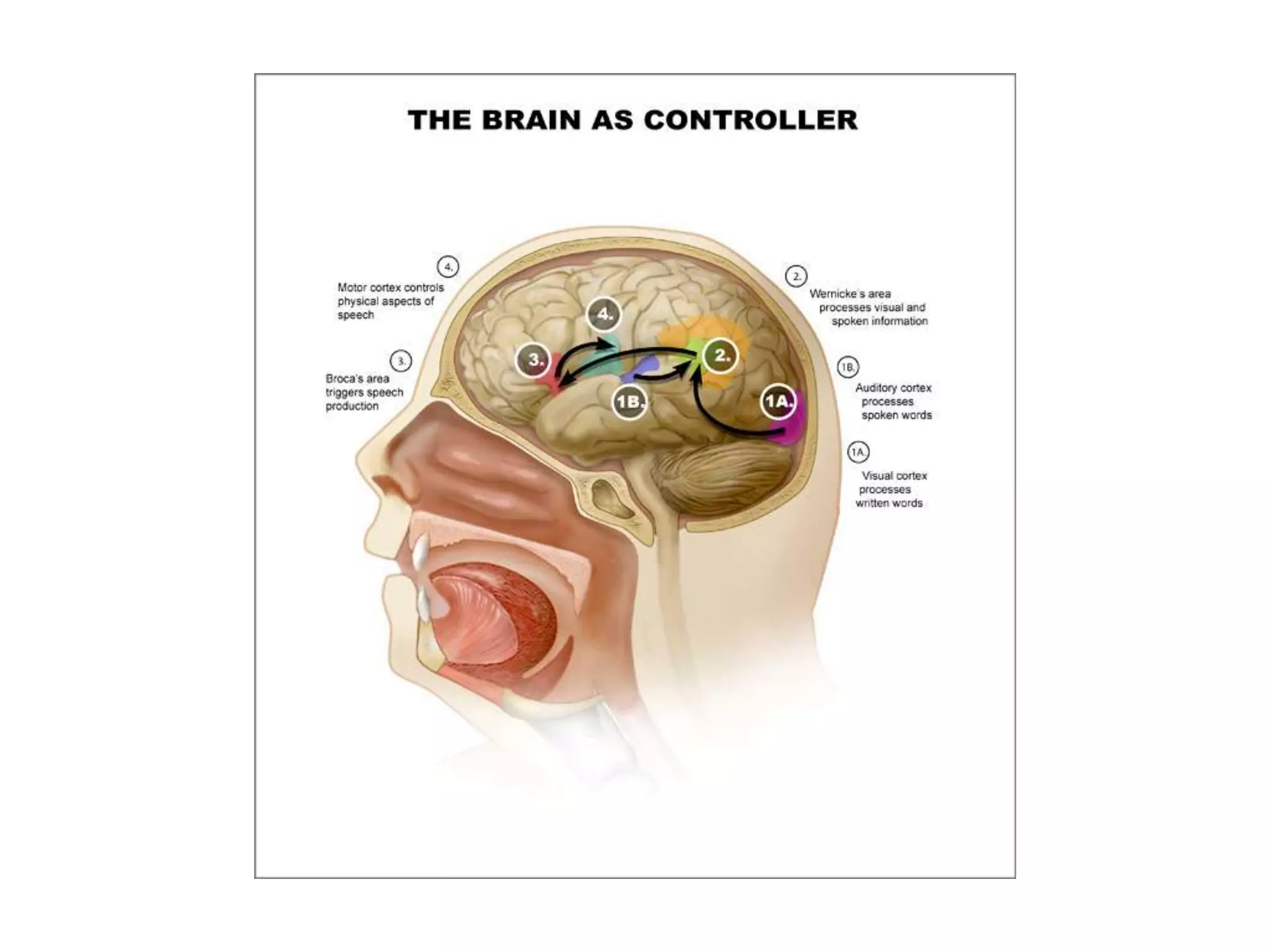

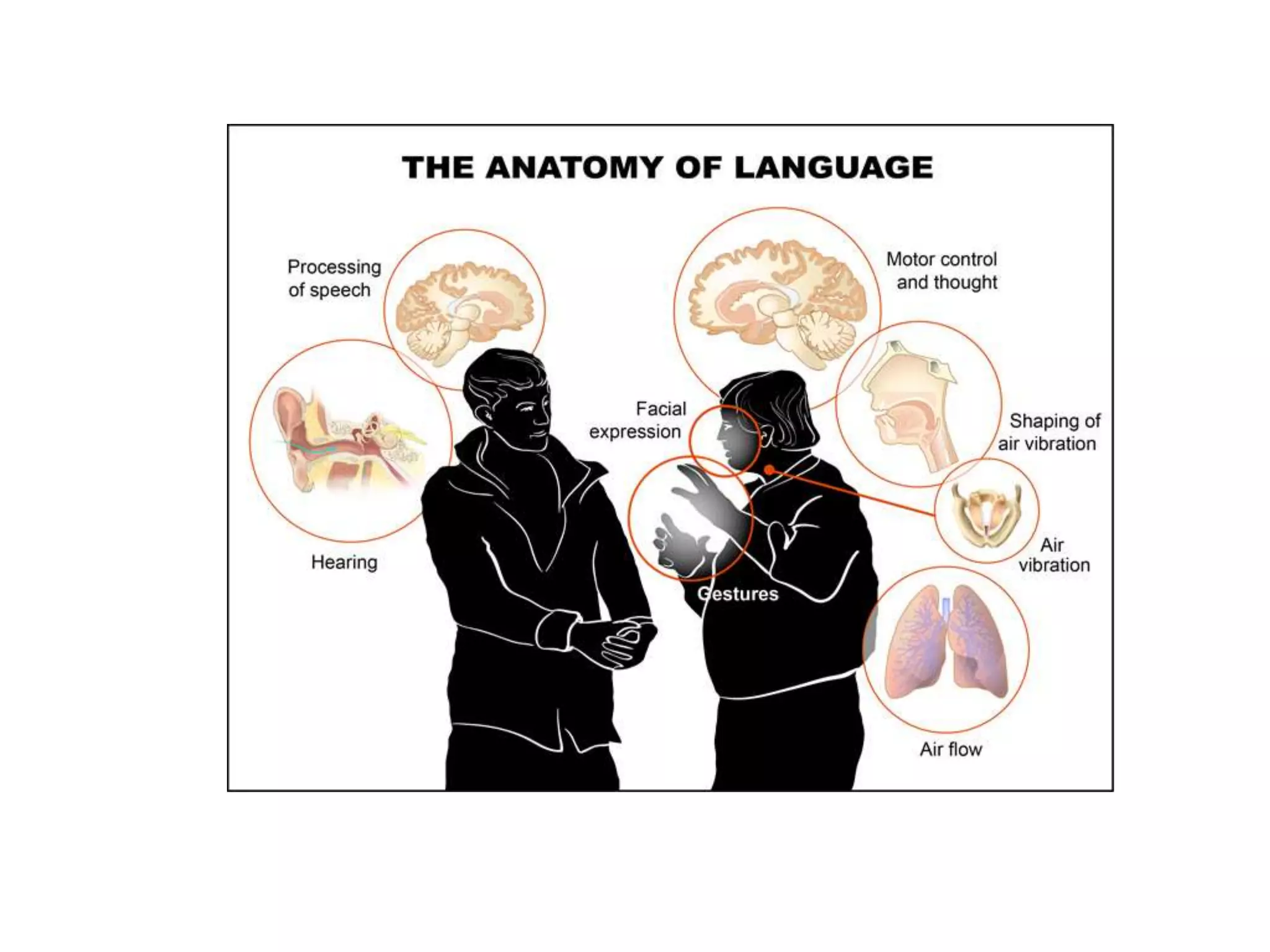

1. It defines language as a complex biological tool used by humans to communicate through organized systems of symbols and rules.

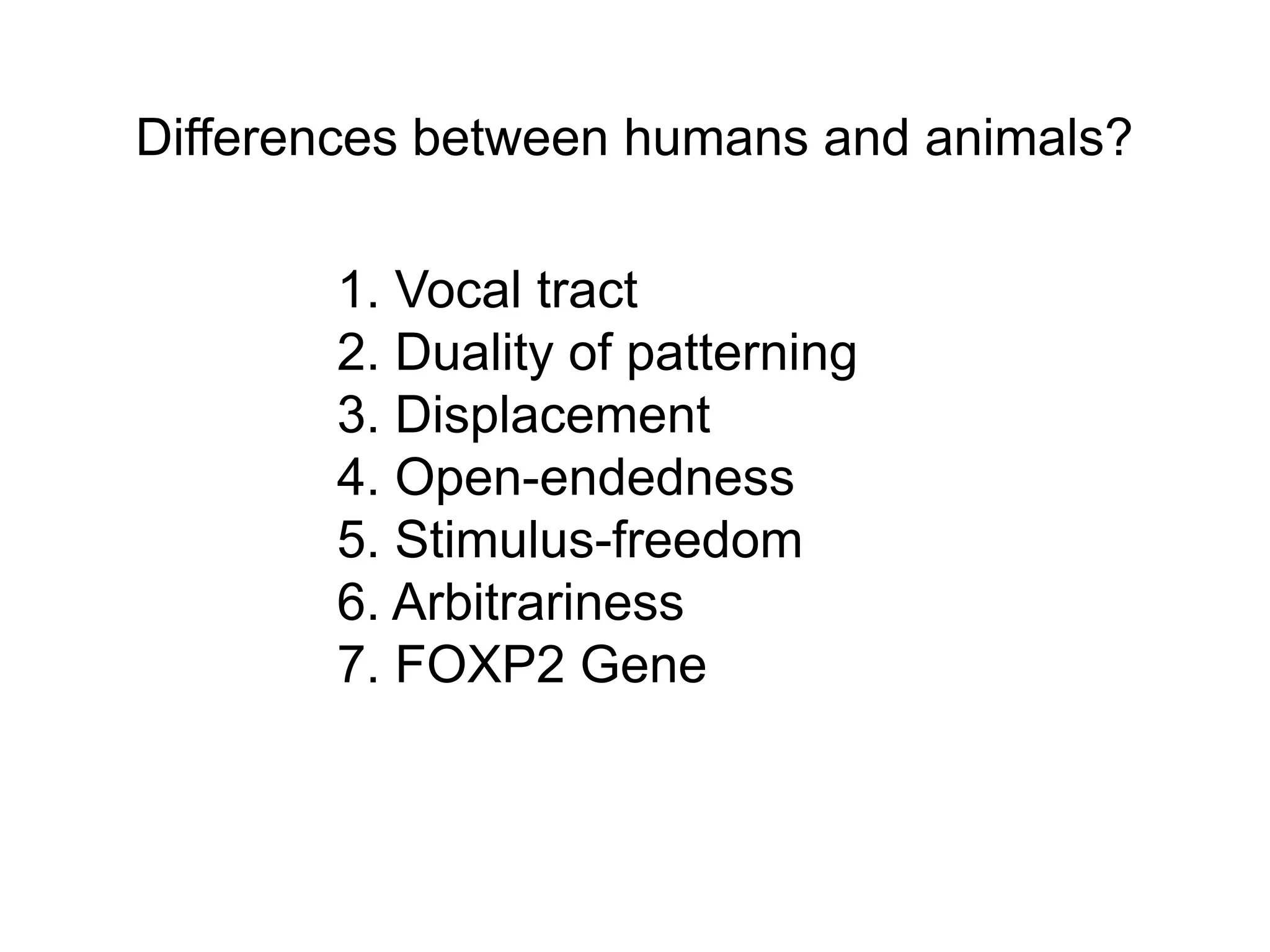

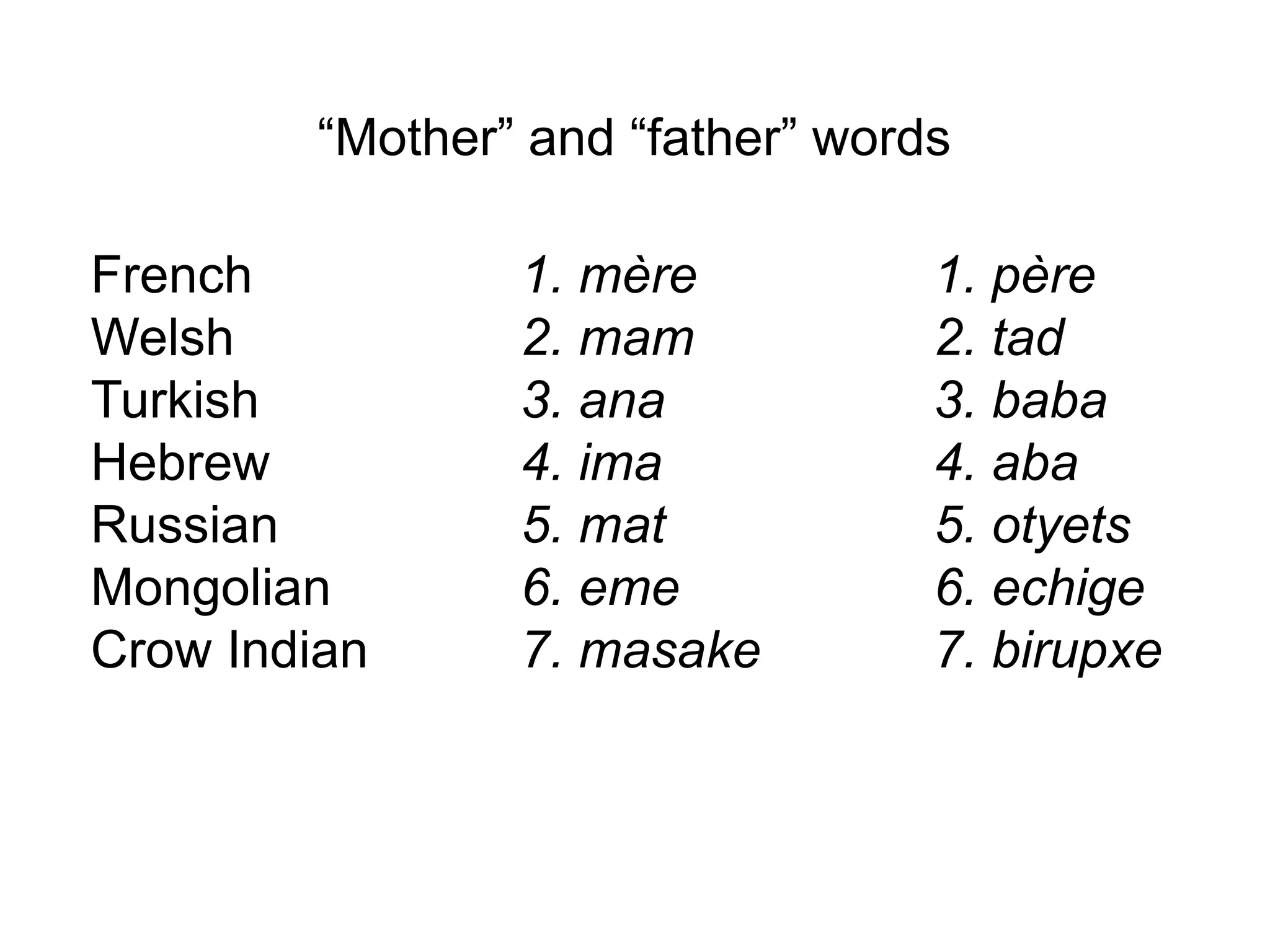

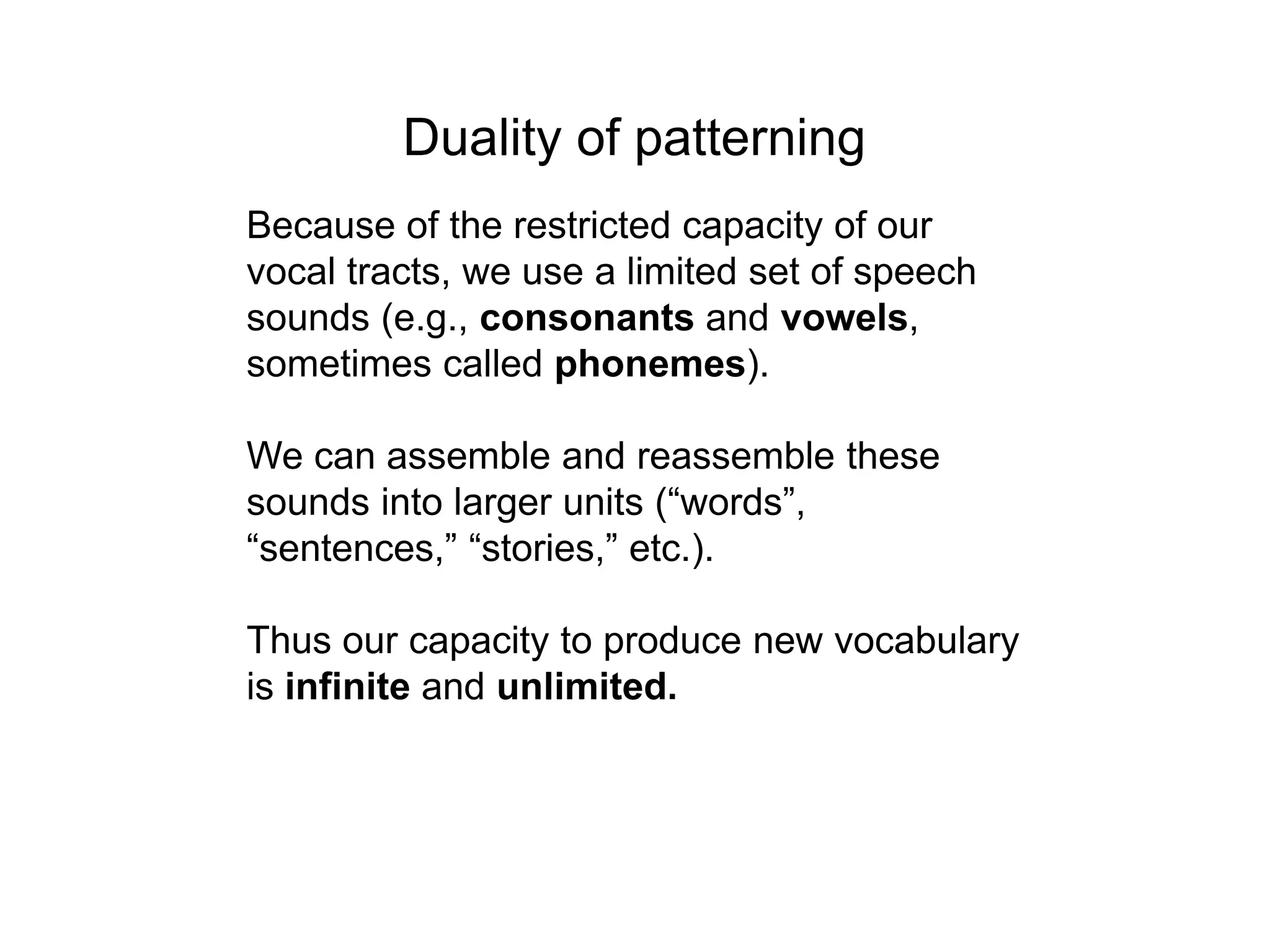

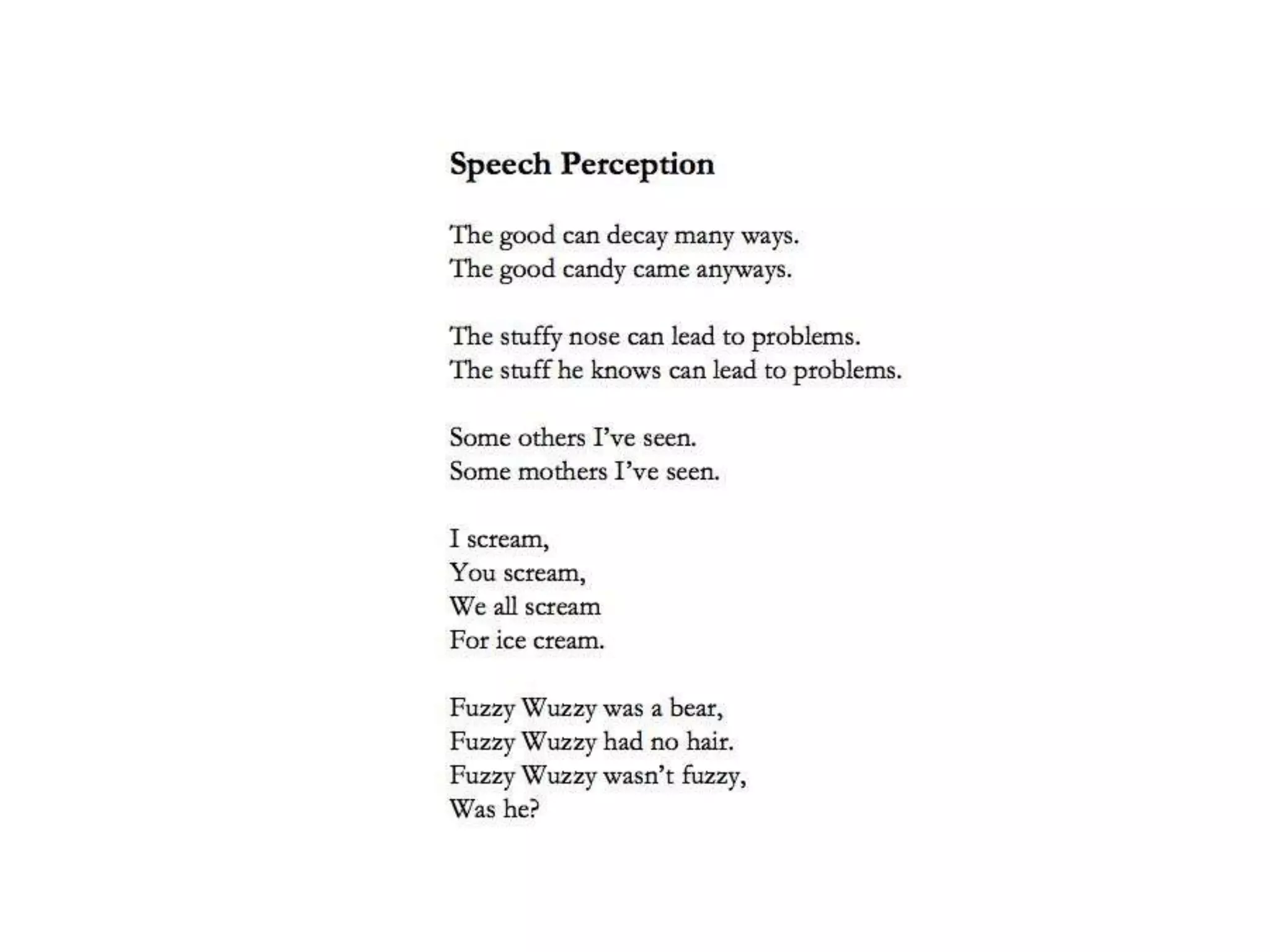

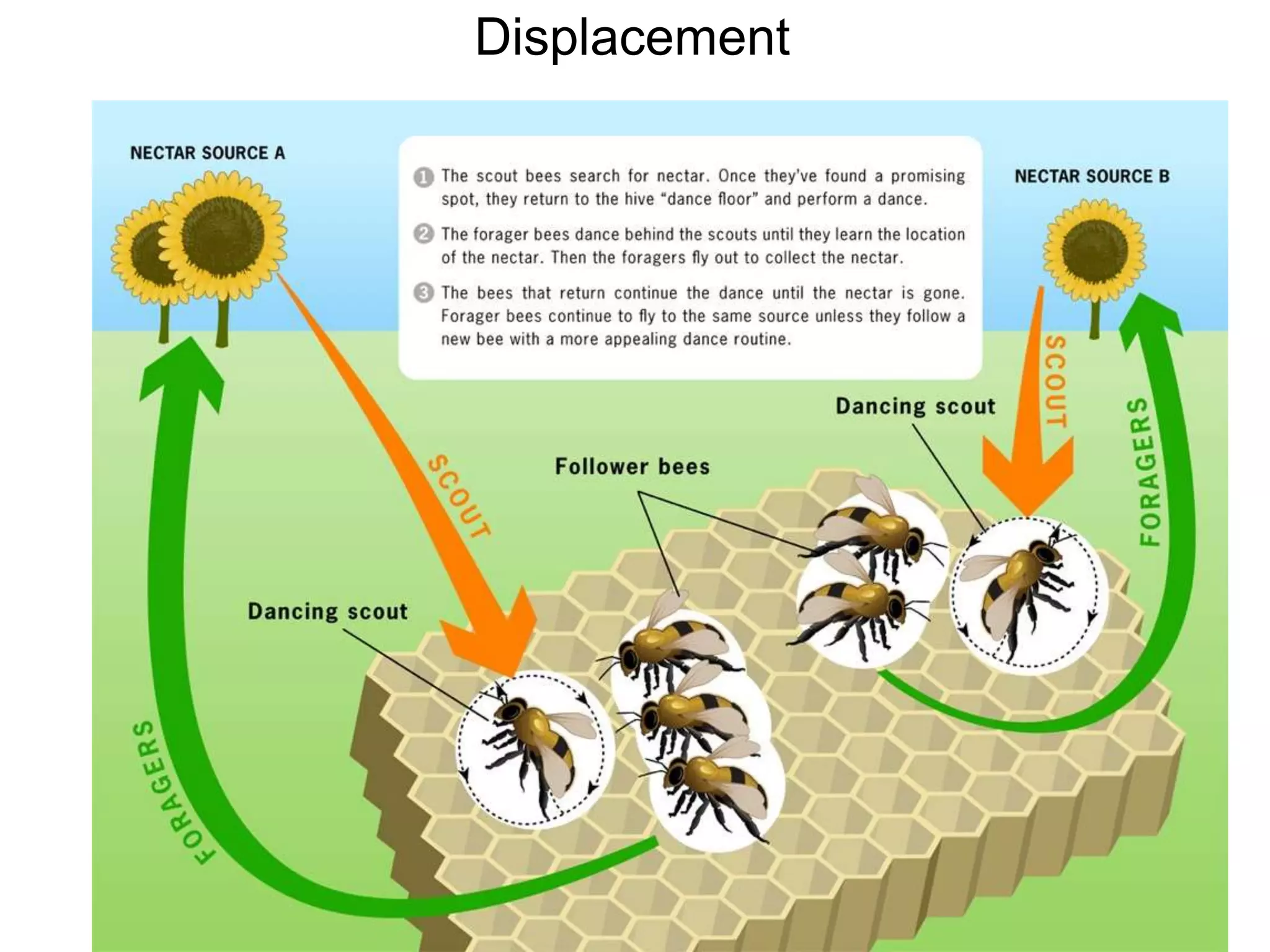

2. It examines some key design features of human language, including duality of patterning, displacement, open-endedness, stimulus-freedom, and arbitrariness.

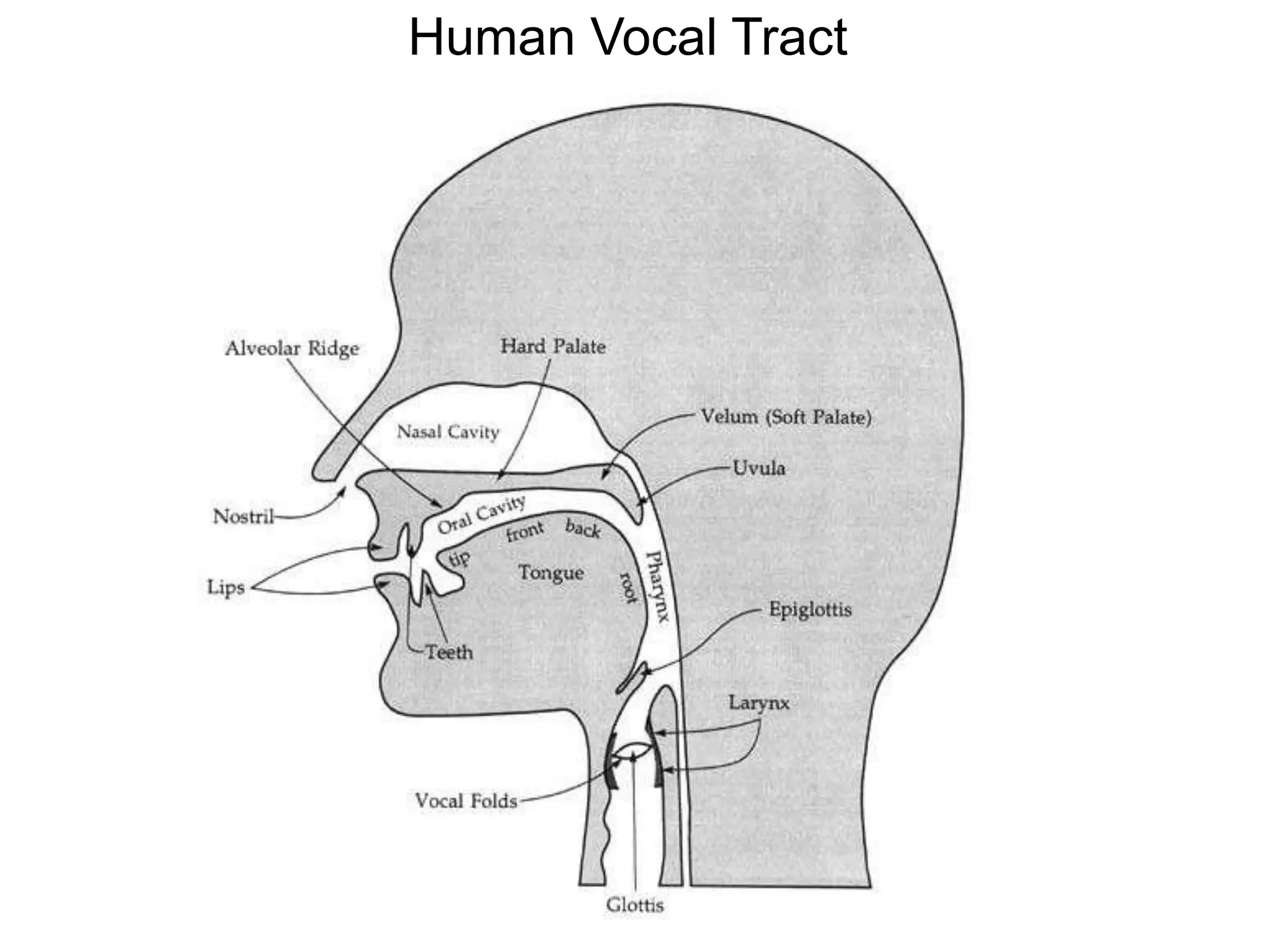

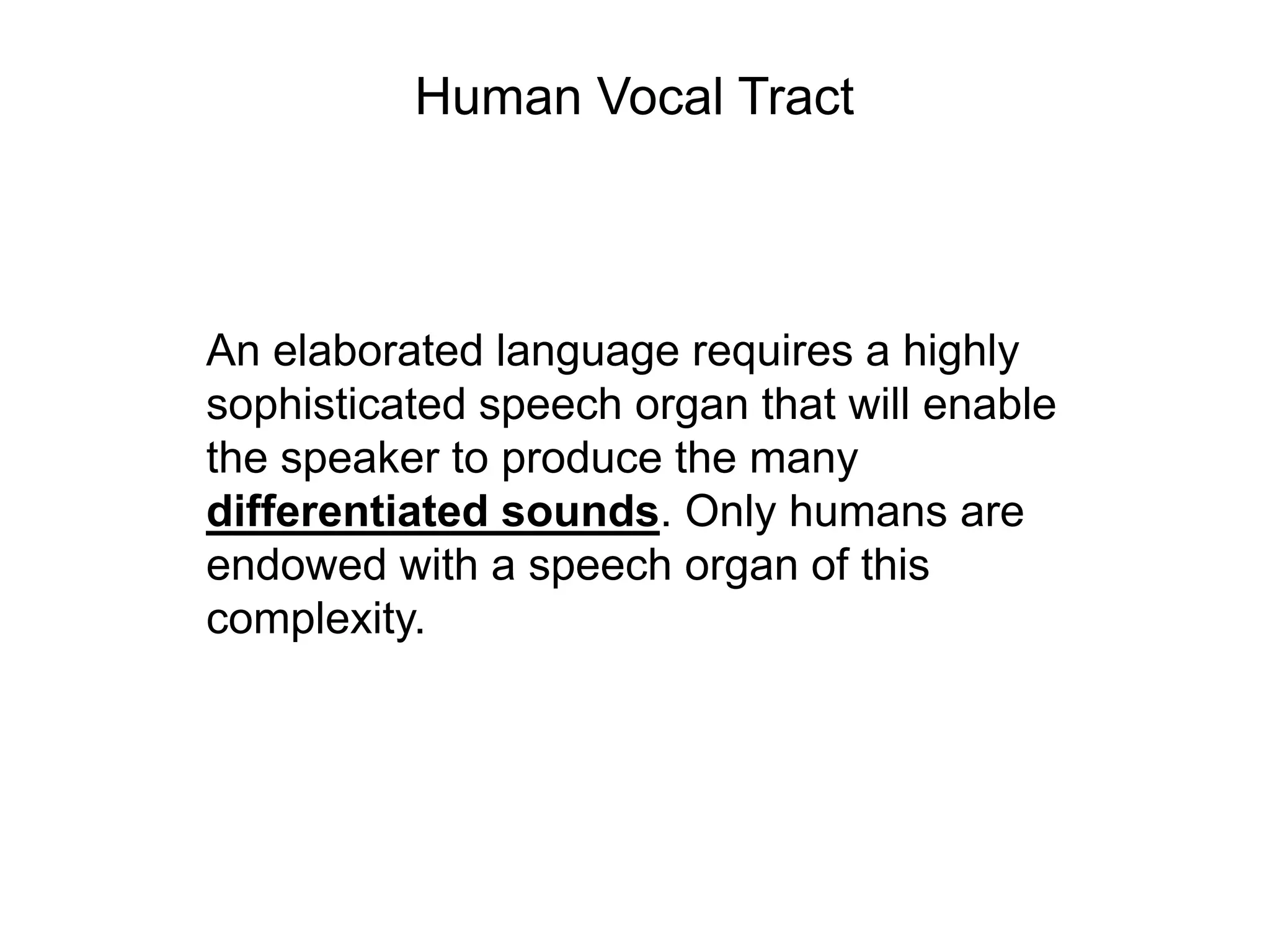

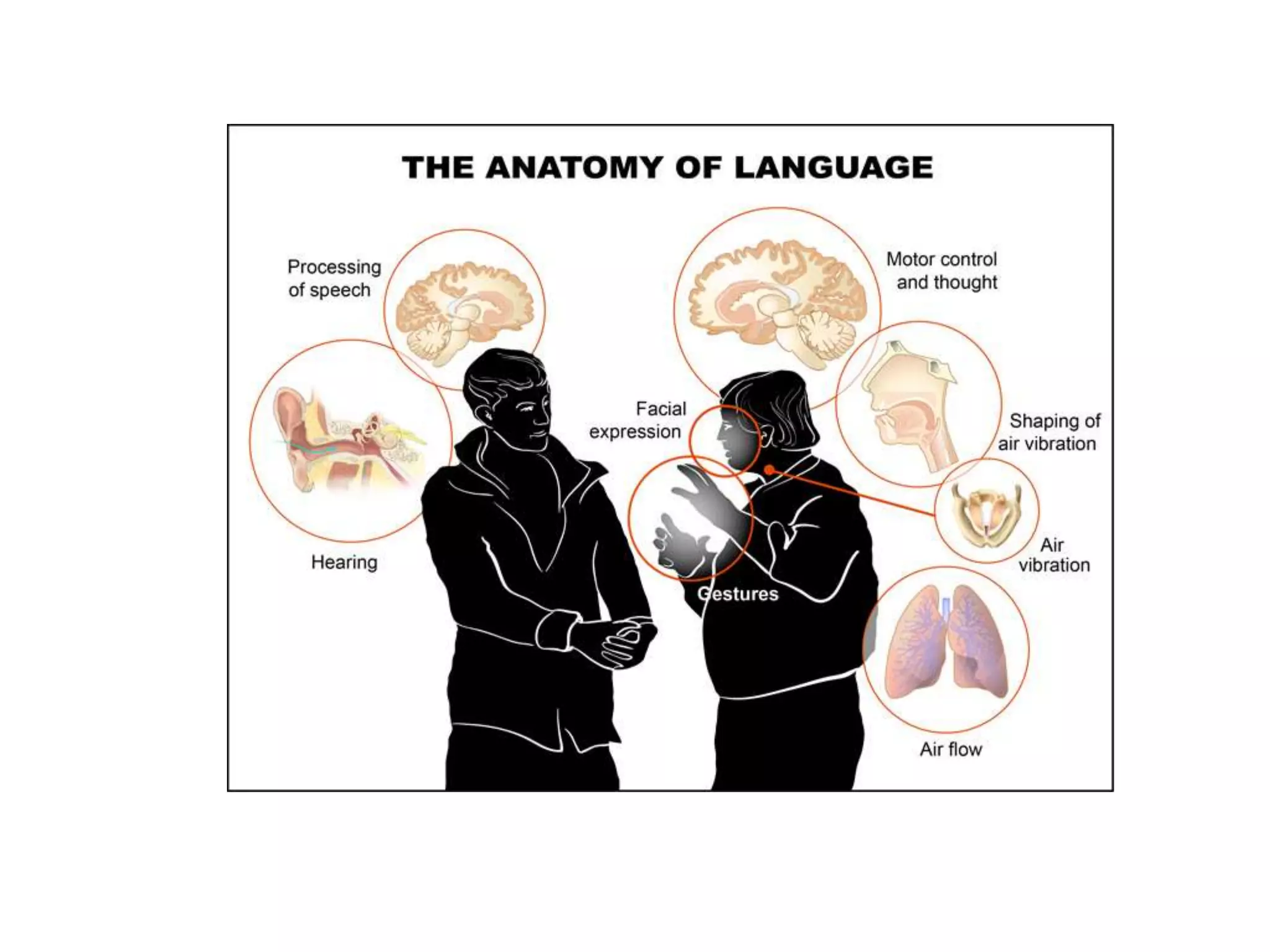

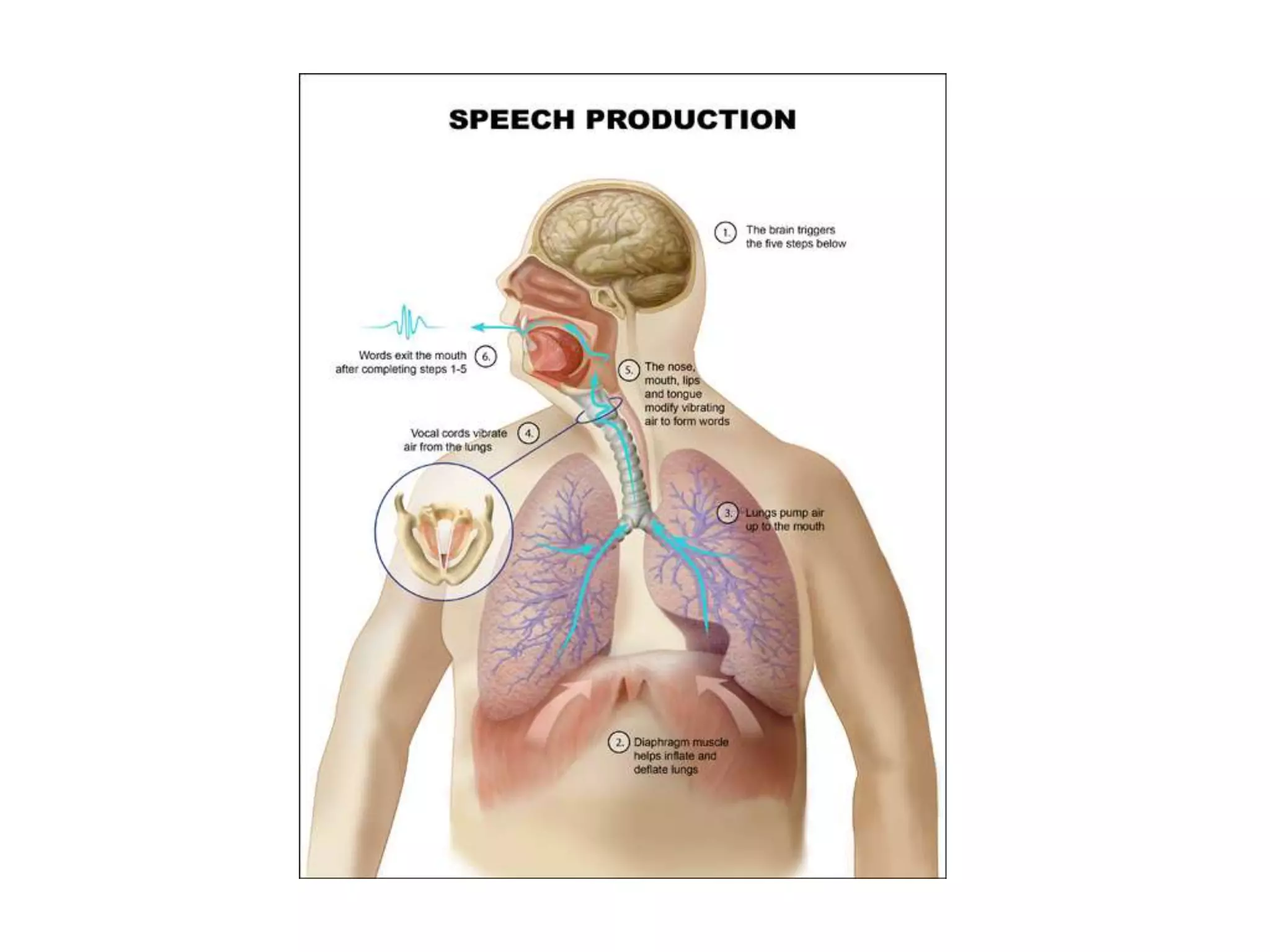

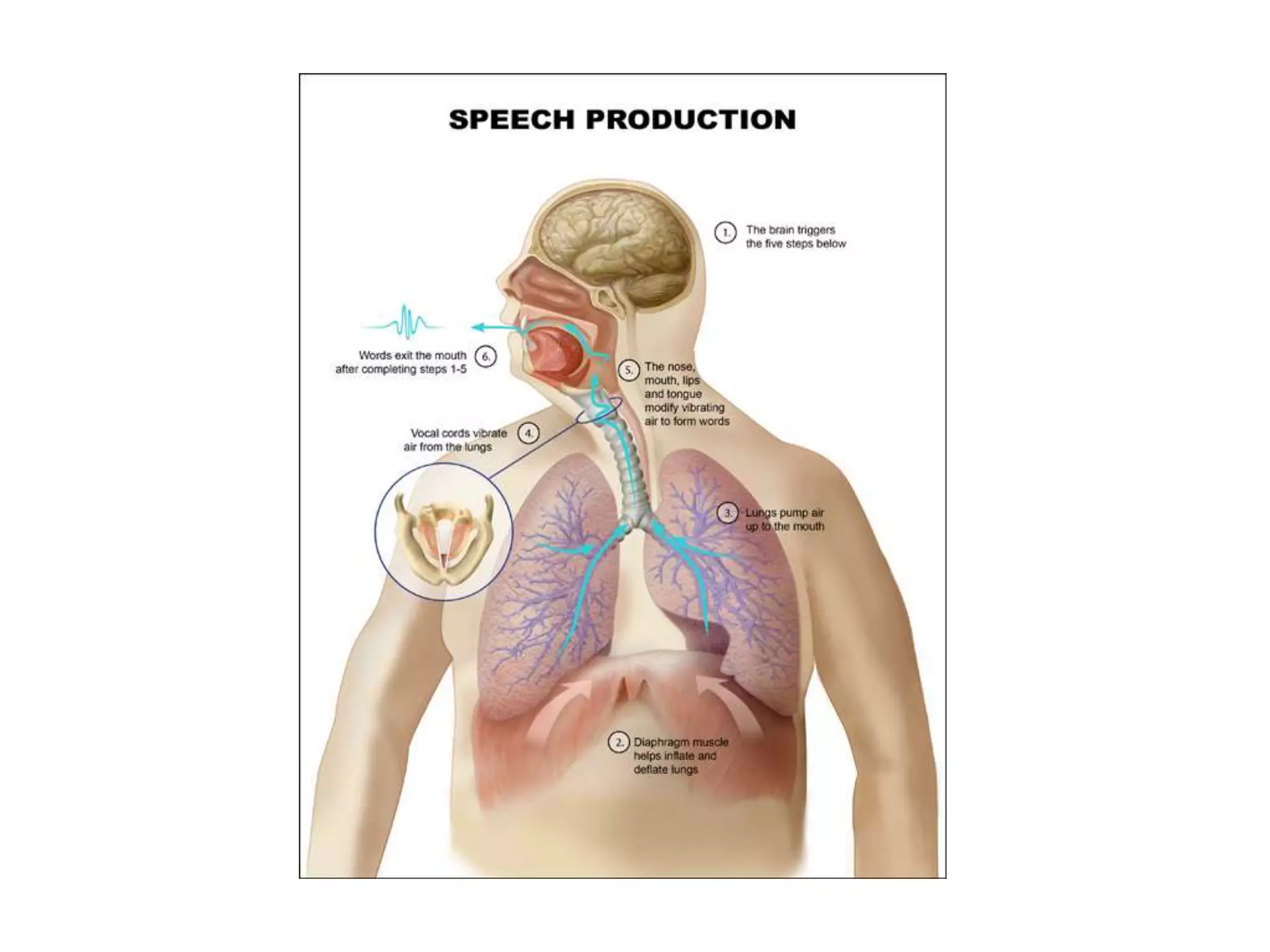

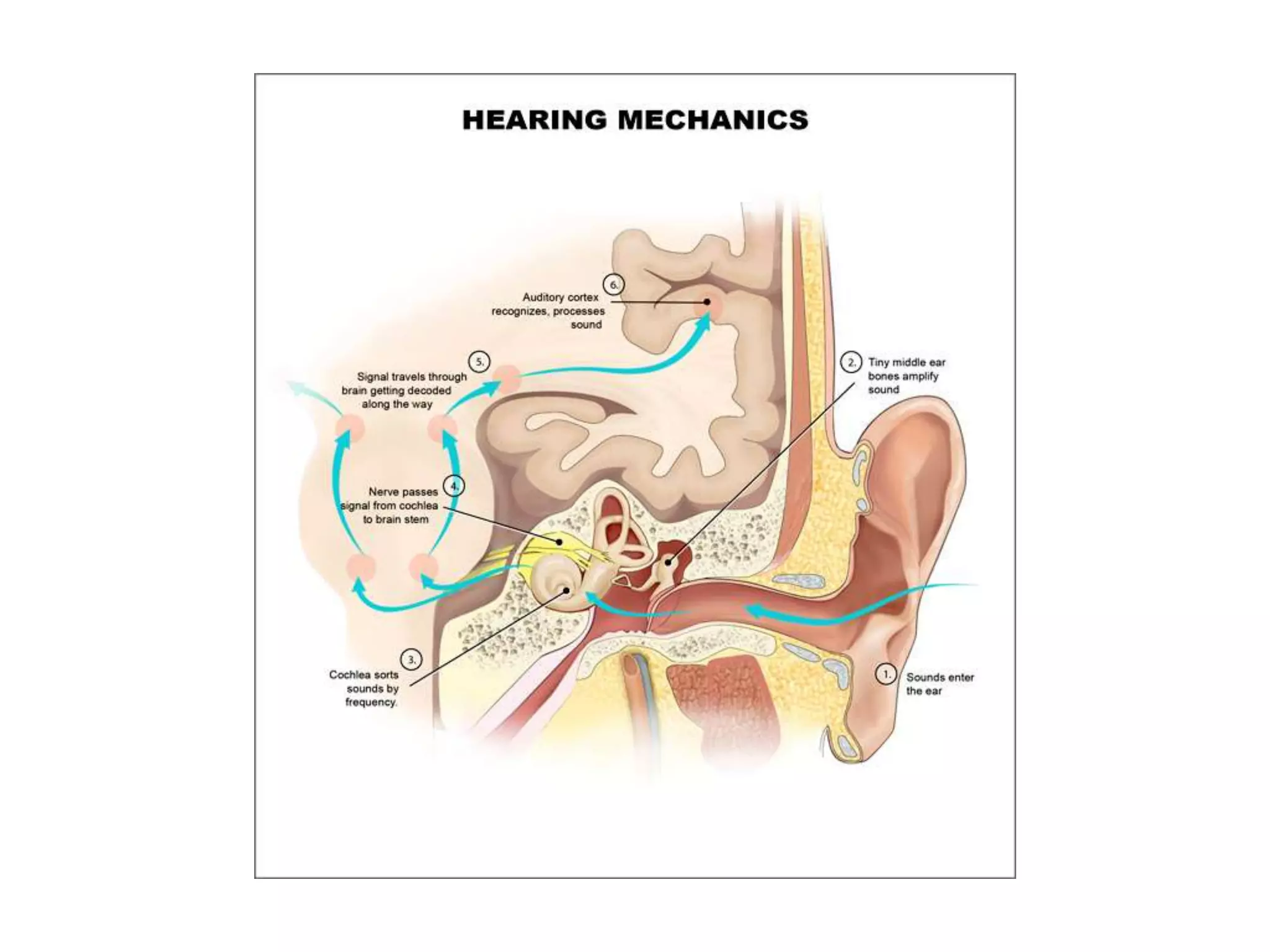

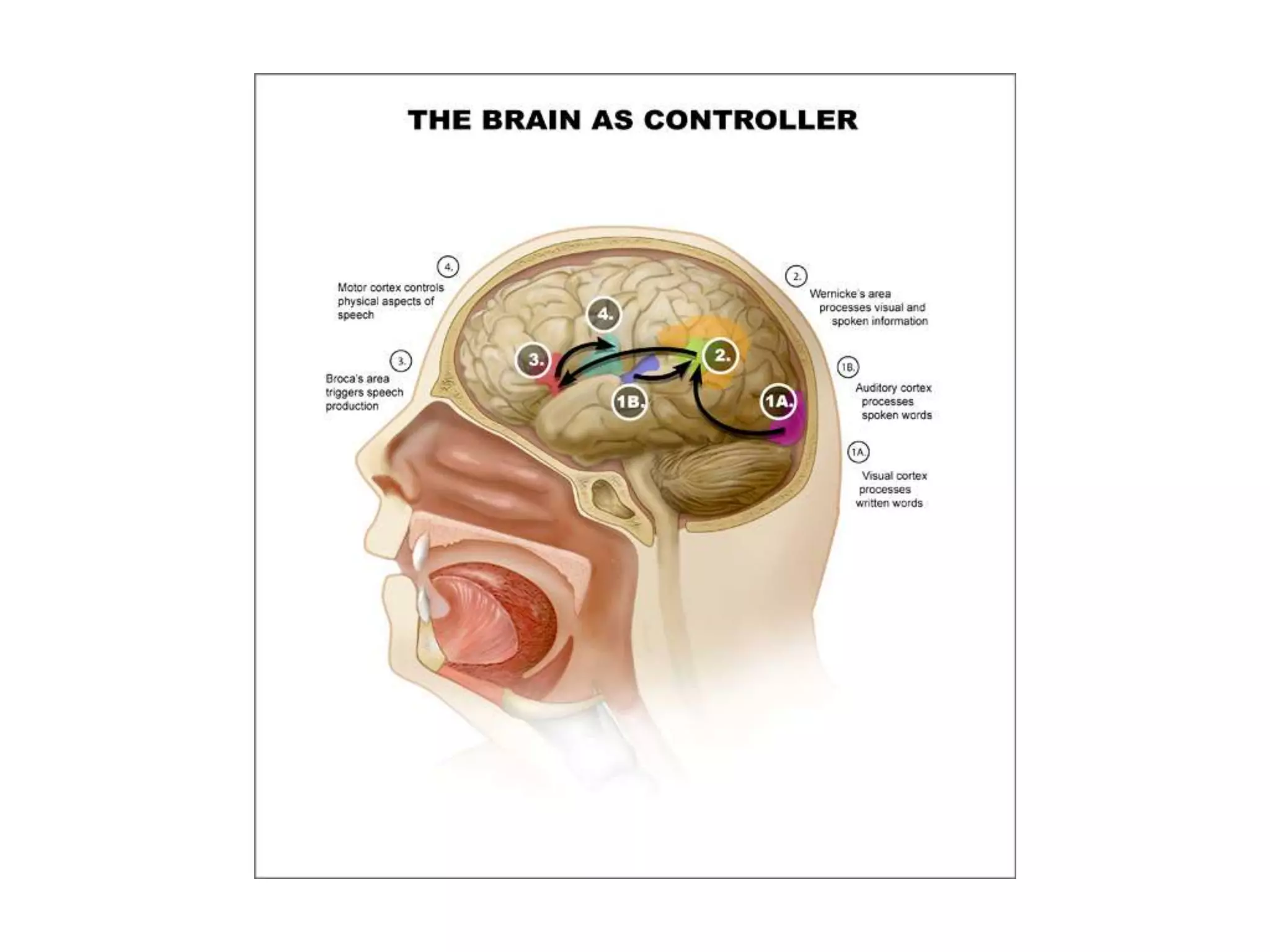

3. It discusses differences between human and animal communication, focusing on the human vocal tract and genes like FOXP2 that enable the complexities of human speech.

![Phonological dialectal variation

Speaking of pronunciation, how do you say:

1. “caught” and “cot”?

2. “Will Mary marry in a merry wedding?”

3. Otter Creek? (a [krik] or a [krIk])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-111104193429-phpapp02/75/Hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-79-2048.jpg)

![African American Phonology

r-deletion is fairly common in AAE, such that

the following words would come out the same:

1. guard [pronounced “god”]

2. sore [pronounced “saw”]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-111104193429-phpapp02/75/Hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-97-2048.jpg)

![African American Phonology

Some speakers also drop their [l] in coda

position:

1. toll [tow]

2. all [aw]

3. help [hep]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-111104193429-phpapp02/75/Hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-98-2048.jpg)

![African American Phonology

Loss of interdental fricative [T] and [D] :

mouth [mawf]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-111104193429-phpapp02/75/Hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-99-2048.jpg)

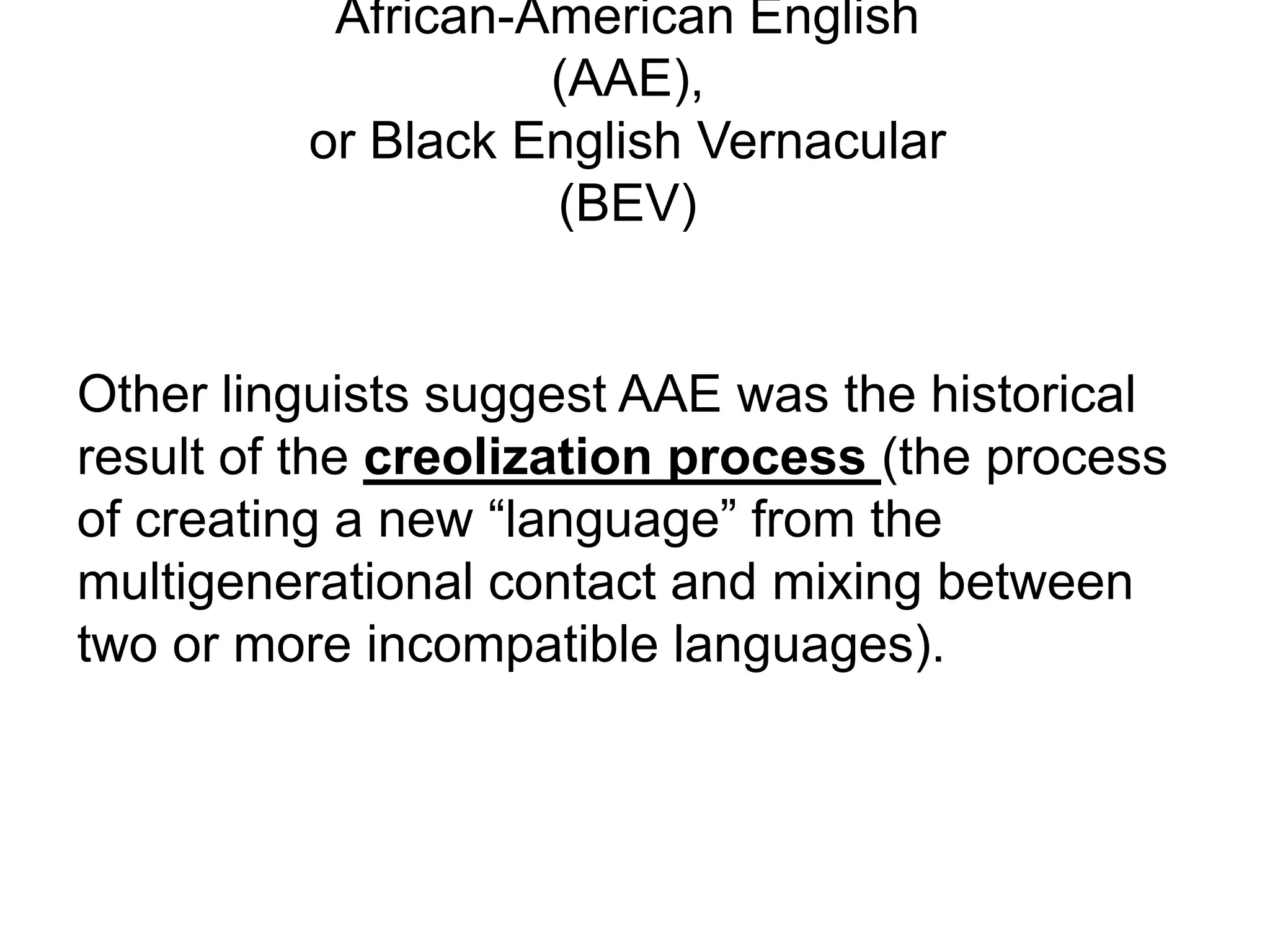

![Textual References

Abrahams, Roger D. 2009 [1964]. Deep Down in the Jungle: Black American Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia.

New Jersey: Folklore Associates, Inc.

Baugh, John. 2000. Beyond Ebonics: Linguistic Pride and Racial Prejudice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Napoli, Lisa. 2007. Language Matters: A Guide to Everyday Questions About Language. Oxford University Press.

Green, Lisa. 2002. African American English: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Labov, William. 1973. Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg. 2006. The Atlas of North American English. Mouton de Gruyter.

Pinker, Steven. 2007. The Language Instinct. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Poplack, Shana, ed. 2000. The English History of African American English. Malden, MA, and Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Rickford, John R. , and Russell J. Rickford. 2000. Spoken Soul: The Story of Black English. New York: John Wiley.

Smitherman, Geneva. 2000. Black Talk: Words and Phrases from the Hood to the Amen Corner. New York: Houghton

Mifflin.

Wolfram, Walt, and Erik R. Thomas. 2002. The Development of African American English. Malden, MA, and Oxford, UK:

Blackwell.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-111104193429-phpapp02/75/Hum1-podcast-week8-f11-language-online-137-2048.jpg)