This document provides an introduction to linguistics. It discusses several key topics:

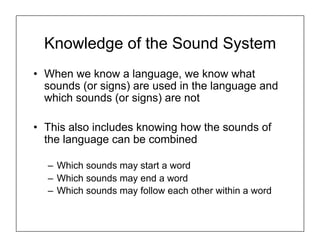

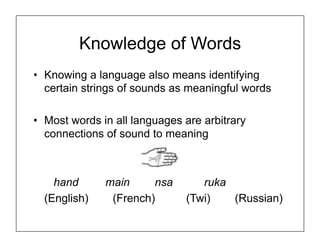

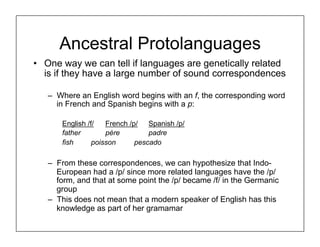

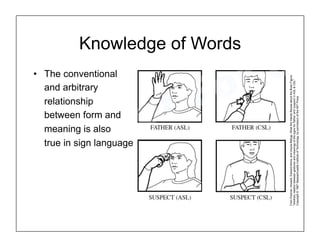

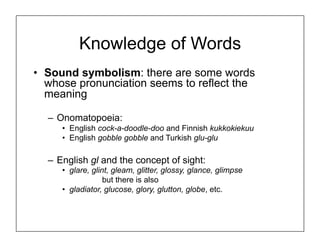

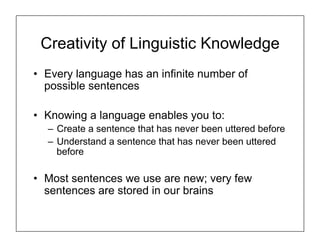

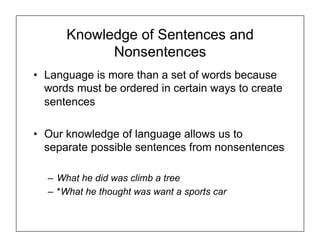

- What is known when someone knows a language, including knowledge of a language's sound system, words, sentences, and creativity.

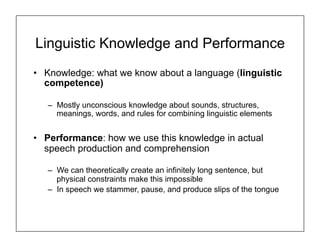

- The difference between competence (linguistic knowledge) and performance (language use).

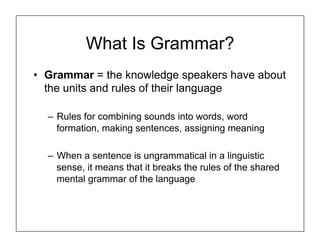

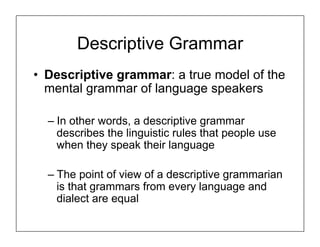

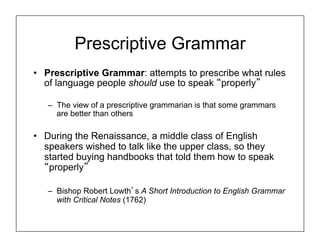

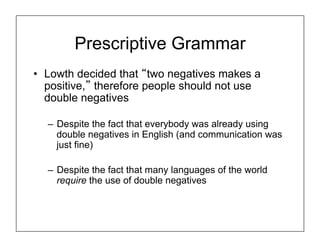

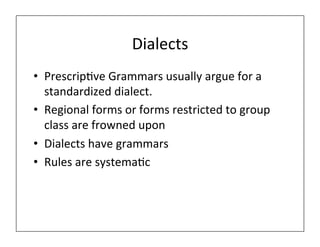

- What grammar is and the difference between descriptive and prescriptive grammars.

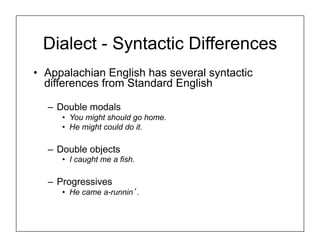

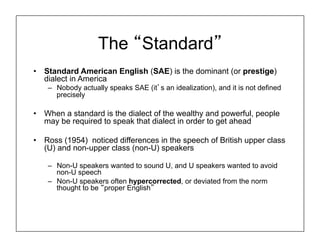

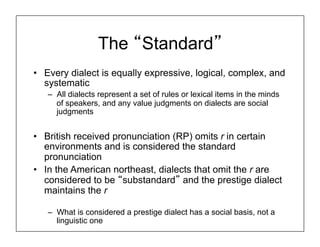

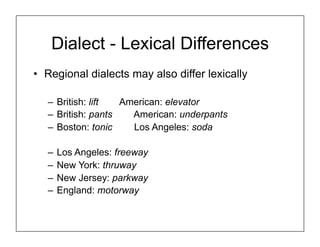

- Dialects, standards, and differences between dialects.

- Language universals and the development of grammar in children.

![Dialect- Phonological

Differences

• There are systematic pronunciation differences

between American and British English

– For example, Americans put stress on the first syllable

of a polysyllabic word, and British speakers put the

stress on the second syllable in words like cigarette,

applicable, formidable, laboratory

– Americans may pronounce the first vowel in data as

[e] or [ei] but vast majority of British speakers would

only use [e]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/whatislanguage-221122174025-ba034eda/85/what_is_language-ppt-pdf-28-320.jpg)