Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is a feeding disorder characterized by avoidance of food due to sensory characteristics, fear of aversive consequences, or lack of interest in eating. This results in insufficient calorie or nutrient intake leading to issues like weight loss, nutritional deficiencies, or interference with functioning. Treatments that have shown promise for ARFID include family-based treatment involving parents supporting exposure to new foods, cognitive-behavioral therapy with elements like food exposure and relaxation training, and hospital-based refeeding programs, some of which utilize tube feeding for severe cases. However, more research is still needed, as existing studies on treating ARFID are limited and no single approach has been proven

![Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; ARFID; family-based

treatment; cognitive-behavioral

therapy; tube feeding

Correspondence to: Jennifer J. Thomas, Ph.D., Eating Disorders

Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General

Hospital, 2

Longfellow Place, Suite 200, Boston, MA 02114.

[email protected] Phone: (617) 643-6306.

Conflicts of interest. Drs. Thomas and Eddy will receive

royalties from Cambridge University Press for the sale of their

book

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Avoidant/Restrictive Food

Intake Disorder: Children, Adolescents, and Adults, scheduled

to be

published in late 2018.

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Curr Opin Psychiatry. Author manuscript; available in PMC

2019 November 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018 November ; 31(6): 425–430.

doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000454.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-6-320.jpg)

![o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

Introduction

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) made its

diagnostic debut in 2013 with

the publication on DSM-5 [1]. ARFID is a reformulation and

expansion of the former DSM-

IV diagnosis of feeding disorder of infancy and early childhood,

and can occur across the

lifespan. The hallmark feature of ARIFD is food avoidance or

restriction, motivated by

sensitivity to the sensory characteristics of food, fear of

aversive consequences of eating, or

lack of interest in eating or food. To meet criteria for ARFID,

the food restriction or

avoidance must lead to one or more consequences such as

weight loss or faltering growth,

nutritional deficiency, dependence on oral nutritional

supplements or tube feeding, or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-8-320.jpg)

![psychosocial impairment. DSM-5 describes three example

presentations of ARFID. In the

first, individuals eat a very limited range of foods due to an

inability to tolerate certain tastes

and textures. In the second, individuals avoid specific foods or

categories of food, or may

stop eating altogether, for fear of aversive consequences of

eating, such as choking,

vomiting, anaphylaxis, or gastrointestinal distress. In the third,

individuals exhibit a lack of

interest in food or eating. It is important to note that these three

presentations are not

mutually exclusive and can co-occur within the same individual

[2].

In addition to the heterogeneity of clinical presentation, ARFID

is also quite diverse in terms

of age, demographics, and comorbidities, highlighting the

difficulty in identifying a

universally applicable treatment approach. For example, ARFID

has been reported in very

young children [3 **], adolescents [4 *], and adults [5], and

several studies have highlighted

that both males and females present with the disorder [6,7].

Other investigations have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-9-320.jpg)

![underscored numerous potential psychiatric and medical

comorbidities, including autism

spectrum disorder [8] and gastrointestinal disorders [6], which

may further individualize

treatment needs.

Available data on the treatment of ARFID

Because ARFID is so new, there is currently no evidence-based

treatment suitable for all

forms of the disorder. A robust literature that pre-dates DSM-5

supports the efficacy of

behavioral interventions for young children with pediatric

feeding disorders [9,10].

However, the generalizability of these approaches to individuals

with ARFID—especially

adolescents and adults—remains unclear. Below we summarize

studies published since the

2013 advent of DSM-5 that describe the treatment of ARFID

specifically. ARFID treatments

recently described in the literature include family-based

treatment and parent training;

cognitive-behavioral approaches; hospital-based re-feeding

including tube feeding; and

adjunctive pharmacotherapy.

Family-based treatment and parent training](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-10-320.jpg)

![Several recently published case reports have described the use

of family-based treatment

(FBT) for children and adolescents with ARFID [11,12,13].

Such approaches are similar to

FBT for anorexia nervosa (AN) in that parents are charged with

the task of feeding, but

differ from FBT for AN in that parents are asked to support

their children in increasing not

only dietary volume, but also dietary variety through repeated

exposure to novel foods. At

least two clinical trials of FBT for ARFID are currently

underway [14,15]. Another case

Thomas et al. Page 2

Curr Opin Psychiatry. Author manuscript; available in PMC

2019 November 01.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-11-320.jpg)

![a

n

u

scrip

t

report described the use of a behavioral parent-training

intervention comprising differential

reinforcement, gradual exposure to novel foods, and

contingency management, resulting in

the acceptance of 30 novel foods in a six-year-old with limited

dietary variety [16].

Cognitive-behavioral approaches

Multiple published case reports and case series have described

the use of various forms of

cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for children [13,17,18] and

adults [19,5] with ARFID.

Common elements across CBT interventions for ARFID include

regular eating [5,13], self-

monitoring of food intake [5], exposure and response prevention

[13,16], relaxation training

[17,16, and behavioral experiments [5]. In one case study, a 16-

year-old boy was able to

significantly increase his consumption of proteins, fruits, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-13-320.jpg)

![vegetables, and significantly

decrease his eating-related distress after 11 sessions of CBT

supplemented with in-home

meal interventions in which his mother reinforced the

consumption of novel foods [16].

Hospital-based re-feeding including tube feeding

Several hospital-based re-feeding programs have reported

positive outcomes on eating and

weight for children and adolescents with low-weight ARFID.

One randomized controlled

study prospectively evaluated the efficacy, among 20 boys and

girls (ages 13–72 months)

with ARFID, of a five-day manualized behavioral treatment

comprising structured

mealtimes, escape extinction, and reinforcement procedures in a

day hospital setting.

Patients randomized to the study treatment exhibited

significantly greater bite acceptance,

grams of food consumed at mealtime, and fewer mealtime

disruptions post-treatment

compared to those in the wait list control condition 3 **].

Another study described treatment

response among 32 children and adolescents with ARFID

treated in an eating disorders](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-14-320.jpg)

![partial hospitalization program, reporting significant increases

in weight and significant

decreases in eating pathology and anxiety from pre- to post-

treatment after an average of

seven weeks [4 *]. Treatment gains were maintained for at least

12 months in the subset of

20 patients who completed a follow-up assessment [20].

Several case studies have described the use of tube feeding to

support inpatient nutritional

rehabilitation among low-weight children and adolescents (ages

5–17 years old) with

ARFID [21,22,23]. Of note, at least two studies have reported

that patients with ARFID

were significantly more likely than those with other eating

disorders to require tube feeding

during inpatient hospitalization [24,25 *]. Although tube

feeding can be a life-saving

measure in some cases of acute food refusal, a recent review

described potentially iatrogenic

effects of tube feeding, including long-term tube dependence

and decreased oral intake [26],

highlighting the urgent need for future research on effective

tube weaning protocols for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-15-320.jpg)

![individuals who require tube feeding.

Adjunctive pharmacotherapy

Three groups have recently published studies on

pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to hospital-

based treatment to facilitate meal consumption and/or weight

gain in low-weight children

and adolescents with ARFID. In one retrospective chart review,

14 children and adolescents

demonstrated a significantly faster rate of weight gain after

(versus before) being prescribed

mirtazapine [27 *]. In another retrospective chart review, nine

youth who took olanzapine

Thomas et al. Page 3

Curr Opin Psychiatry. Author manuscript; available in PMC

2019 November 01.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-16-320.jpg)

![a

n

u

scrip

t

showed significant increases in weight from pre- to post-

treatment [28 *]. The only double-

blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of medication for

ARFID evaluated the efficacy of

D-cycloserine (DCS) augmentation of a five-day behavioral

intervention for chronic and

severe food refusal in 15 children (ages 20–58 months). Those

randomized to the DCS

condition showed a significantly greater percentage of bites

rapidly swallowed, and

significantly fewer mealtime disruptions, compared to those

receiving placebo [29 **].

Summary of available data

Available data on the treatment of ARFID are sparse, and

limited to child and adolescent

populations. Studies are limited to case reports, case series, and

retrospective chart reviews,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-18-320.jpg)

![with a handful of randomized controlled trials in very young

children treated in day hospital

settings. Findings in adults are limited to case reports, with no

larger-scale studies on

patients over the age of 18. Several groups are currently

evaluating the efficacy of new

psychological treatments for ARFID [14,15,30], but results have

not yet been published.

Case reports and case series have highlighted the promise of

family-based treatment,

cognitive-behavioral therapy, and hospital-based re-feeding,

with pharmacotherapy as an

adjunctive rather than a stand-alone treatment. Prospective

randomized controlled trials are

needed, particularly for adolescents and adults.

The cognitive-behavioral formulation of ARFID

To fill the need for manualized treatments suitable for testing in

randomized controlled

trials, our team at Massachusetts General Hospital has

developed a novel form of cognitive-

behavioral therapy for ARFID that is currently being tested in

an open trial in which 20

participants ages 10–22 are receiving either individual of

family-based versions of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-19-320.jpg)

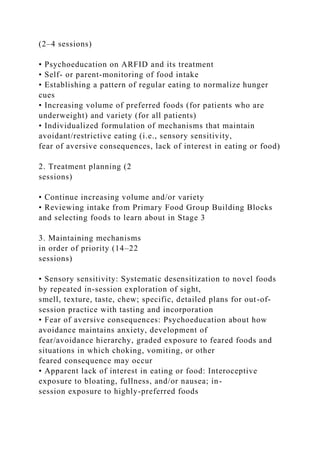

![treatment [30,31 **]. The goal of CBT-AR is to help patients

achieve a healthy weight,

resolve nutrition deficiencies, increase variety to include

multiple foods from each of the

five basic food groups, eliminate dependence on nutritional

supplements, and reduce

psychosocial impairment. CBT-AR is based on our cognitive-

behavioral conceptualization

of the disorder (Figure 1), which posits that some individuals

have a biological

predisposition to sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive

consequences, and/or lack of interest in

food or eating [2]. Specifically, those with sensory sensitivity

may have heightened response

to unfamiliar tastes and smells, those with fear of aversive

consequences may have high trait

anxiety, and those with lack of interest in eating or food may

have lower homeostatic or

hedonic appetites.

The CBT model posits that individuals with such

predispositions will be vulnerable to

developing negative feelings and predictions about eating. For

example, the patient with](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-20-320.jpg)

![children, adolescents, and adults with ARFID (ages 10 and up).

CBT-AR is a flexible,

modular treatment designed to last approximately 20 (for

patients who are not underweight)

to 30 (for patients who have significant weight to gain) sessions

over six to 12 months. CBT-

AR is appropriate for individuals with ARFID who are

medically stable, currently accepting

at least some food by mouth, and not receiving tube feeding.

Patients who are under the age

of 16 and/or older adolescents and young adult patients who

have significant weight to gain

can be offered a family-supported version of CBT-AR, whereas

patients ages 16 years and

up without significant weight to gain can be treated with an

individual version.

CBT-AR proceeds through four broad stages (Table 1) [31 **].

In Stage 1, the therapist

provides psychoeducation about ARFID and CBT-AR. In

addition, the therapist encourages

the patient to establish a pattern of regular eating and self-

monitoring by relying primarily

on preferred foods, but also encourages early change by asking

the patient who is not](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-24-320.jpg)

![clinical needs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of funding. The authors would like to gratefully

acknowledge funding for the work described in this

paper from the National Institute of Mental Health

(1R01MH108595), Hilda and Preston Davis Foundation, and

American Psychological Foundation.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period

of review, have been

highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (DSM-5).

American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

2. Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N et al. Avoidant/restrictive

food intake disorder: a three-

dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for

etiology and treatment. Current psychiatry

reports. 2017; 19:54. [PubMed: 28714048]

3 **. Sharp WG, Stubbs KH, Adams H et al. Intensive, manual-

based intervention for pediatric feeding

disorders: results from a randomized pilot trial. Journal of

pediatric gastroenterology and

nutrition. 2016; 62:658–63.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-30-320.jpg)

![t

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

[PubMed: 26628445]

4 *. Ornstein RM, Essayli JH, Nicely TA et al. Treatment of

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-32-320.jpg)

![a cohort of young patients in a partial hospitalization program

for eating disorders. International

Journal of Eating Disorders. 2017; 50:1067–74.

This retrospective chart review describes outcomes for children

and adolescents with ARFID treated in

a partial hospitalization program for eating disorders, which

utilizes techniques from family-

based treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

[PubMed: 28644568]

5. Steen E, Wade TD. Treatment of co‐occurring food avoidance

and alcohol use disorder in an adult:

possible avoidant restrictive food intake disorder?. International

Journal of Eating Disorders. 2018;

51:373–377. [PubMed: 29394459]

6. Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, Hastings E et al. Prevalence of DSM‐5

avoidant/restrictive food intake

disorder in a pediatric gastroenterology healthcare network.

International Journal of Eating

Disorders. 2015; 48:464–70. [PubMed: 25142784]

7. Forman SF, McKenzie N, Hehn R et al. Predictors of outcome

at 1 year in adolescents with DSM-5

restrictive eating disorders: report of the national eating

disorders quality improvement

collaborative. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014; 55:750–6.

[PubMed: 25200345]

8. Lucarelli J, Pappas D, Welchons L, Augustyn M. Autism

spectrum disorder and avoidant/restrictive

food intake disorder. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-33-320.jpg)

![Pediatrics. 2017; 38:79–80. [PubMed:

27824638]

9. Lukens CT, Silverman AH. Systematic review of

psychological interventions for pediatric feeding

problems. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2014 6

13;39(8):903–17. [PubMed: 24934248]

10. Sharp WG, Volkert VM, Scahill L et al. A systematic review

and meta-analysis of intensive

multidisciplinary intervention for pediatric feeding disorders:

how standard is the standard of

care?. The Journal of pediatrics. 2017; 181:116–24. [PubMed:

27843007]

11. Fitzpatrick KK, Forsberg SE, Colborn. Family-based

therapy for avoidant restrictive food intake

disorder: Families Facing Food Neophobias In: Family Therapy

for Adolescent Eating and Weight

Disorders. 1 Loeb K. (Ed.), Le Grange D. (Ed.), Lock J. (Ed.).

New York: Routledge; 2015 pp.

276–296

12. Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating

disorders: current perspectives on

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth.

Neuropsychiatric disease and

treatment. 2016; 12:213–218. [PubMed: 26855577]

13. Thomas JJ, Brigham KS, Sally ST et al. Case 18–2017—an

11-year-old girl with difficulty eating

after a choking incident. New England journal of medicine.

2017; 376:2377–86. [PubMed:

28614676]

14. Lesser J, Eckhardt S, Ehrenreich-May J, et al. Integrating](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-34-320.jpg)

![family based treatment with the unified

protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional 351

disorders: a novel treatment for

avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. Clinical Teaching Day

presentation at the International

Conference on Eating Disorders; 2017; Prague, Czech Republic.

15. Sadeh-Sharvit S, Robinson A, Lock J. FBT-ARFID for

younger patients: lessons from a

randomized controlled trial. Workshop presented at the

International Conference on Eating

Disorders; 2018; Chicago, Illinois.

16. Murphy J, Zlomke KR. A behavioral parent-training

intervention for a child with avoidant/

restrictive food intake disorder. Clinical Practice in Pediatric

Psychology. 2016; 4:23–34.

17. Fischer AJ, Luiselli JK, Dove MB. Effects of clinic and in-

home treatment on consumption and

feeding-associated anxiety in an adolescent with

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Clinical

Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2015; 3:154–166.

18. Bryant Waugh R Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder:

an illustrative case example.

International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013; 46:420–3.

[PubMed: 23658083]

19. King LA, Urbach JR, Stewart KE. Illness anxiety and

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder:

cognitive-behavioral conceptualization and treatment. Eating

behaviors. 2015; 19:106–9.

[PubMed: 26276708]

Thomas et al. Page 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-35-320.jpg)

![o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

20. Bryson AE, Scipioni AM, Essayli JH et al. Outcomes of

low‐weight patients with avoidant/

restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa at

long‐term follow‐up after treatment in a

partial hospitalization program for eating disorders.

International Journal of Eating Disorders.

2018; 51:470–474. [PubMed: 29493804]

21. Guvenek-Cokol PE, Gallagher K, Samsel C. Medical

traumatic stress: a multidisciplinary approach](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-37-320.jpg)

![for iatrogenic acute food refusal in the inpatient setting.

Hospital pediatrics. 2016; 6:693–8.

[PubMed: 27803075]

22. Pitt PD, Middleman AB. A focus on behavior management

of avoidant/restrictive food intake

disorder (ARFID): a case series. Clinical pediatrics. 2018;

57:478–80. [PubMed: 28719985]

23. Schermbrucker J, Kimber M, Johnson N et al.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in an 11-

year old south American boy: medical and cultural challenges.

Journal of the Canadian Academy

of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017; 26:110–113.

[PubMed: 28747934]

24. Strandjord SE, Sieke EH, Richmond M, Rome ES.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: illness

and hospital course in patients hospitalized for nutritional

insufficiency. Journal of Adolescent

Health. 2015; 57:673–8. [PubMed: 26422290]

25 *. Peebles R, Lesser A, Park CC et al. Outcomes of an

inpatient medical nutritional rehabilitation

protocol in children and adolescents with eating disorders.

Journal of eating disorders. 2017; 5:1–

14.

This paper describes the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

(CHOP) Malnutrition Protocol for the

inpatient re-feeding of children and adolescents with restrictive

eating disorders, including

ARFID.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-38-320.jpg)

![[PubMed: 28053702]

26. Dovey TM, Wilken M, Martin CI, Meyer C. Definitions and

clinical guidance on the enteral

dependence component of the avoidant/restrictive food intake

disorder diagnostic criteria in

children. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2018;

42:499–507.

27 *. Gray E, Chen T, Menzel J et al. Mirtazapine and weight

gain in avoidant and restrictive food

intake disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child &

Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;

57:288–9.

This retrospective chart review describes adjuctive

pharmacotherapy with mirtazipine for children and

adolescents with ARFID.

[PubMed: 29588055]

28 *. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of

olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant

restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an

eating disorders program.

Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2017;

27:920–2.

This retrospective chart review describes adjunctive

pharmacotherapy with olanazapine for children

and adolescents with ARFID.

[PubMed: 29068721]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-39-320.jpg)

![papers have

addressed similar questions as those addressed in this article.

All study

procedures were approved by the University of Kansas

Institutional Re-

view Board (Study IRB STUDY00003260). Authors complied

with APA

ethical standards in the treatment of their participants. The

manuscript has

not been and is not posted on a website. Jenna P. Tregarthen is a

co-founder

and shareholder of Recovery Record, Inc. Jenna P. Tregarthen

made a

substantial contribution as part of data collection and curation

and ap-

proved the final manuscript, but she did not participate in the

analysis,

interpretation, or drafting of the manuscript. Kelsie T. Forbush

received an

industry-sponsored grant from Recovery Record, Inc. No other

authors

have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Cheri A.

Levinson, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences,

University of

Louisville, Life Sciences Building 317, Louisville, KY 40292.

E-mail:

[email protected]

T

hi

s

do](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-53-320.jpg)

![oa

dl

y.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology

© 2019 American Psychological Association 2020, Vol. 129,

No. 2, 177–190

ISSN: 0021-843X http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/abn0000477

177

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7741-1498

mailto:[email protected]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/abn0000477

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious mental illnesses associated

with negative health consequences, significant impairment, and

high mortality (Crow et al., 2009; Rome & Ammerman, 2003;

Stice, Marti, & Rohde, 2013). Peak age of ED onset is during

adolescence, between 16 and 20 years of age (Stice et al.,

2013).

Although EDs most commonly develop during this period, evi-

dence suggests that eating pathology may persist, return, or de-

velop throughout an individual’s life (Fulton, 2016; Patrick &

Stahl, 2009). Indeed, studies indicate that ED symptoms occur

across all developmental stages, with approximately 11% of

adults

aged 42–55 and 4% of adults aged 60 –70 engaging in ED

behav-

iors, such as binge eating, laxative/diuretic misuse, or self-

induced

vomiting (Mangweth-Matzek et al., 2006; Marcus, Bromberger,

Wei, Brown, & Kravitz, 2007). The presence of disordered](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-58-320.jpg)

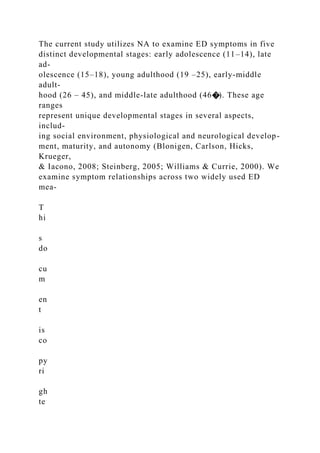

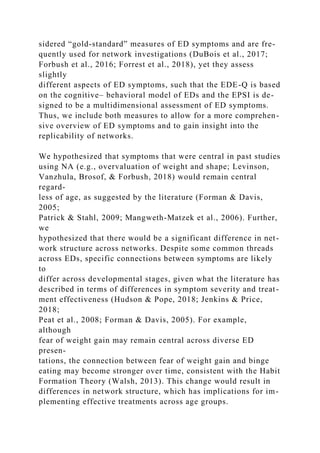

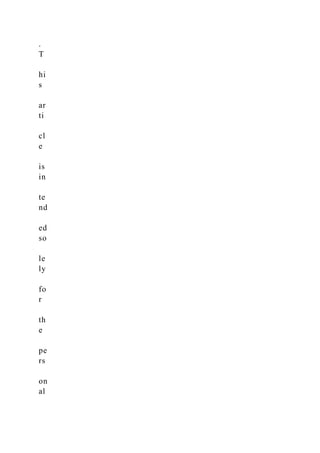

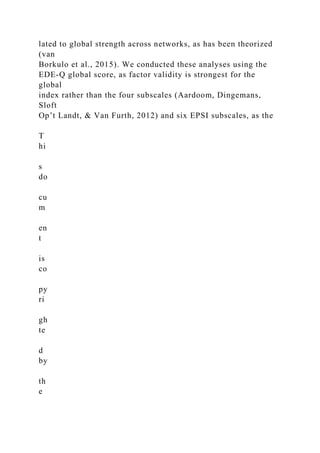

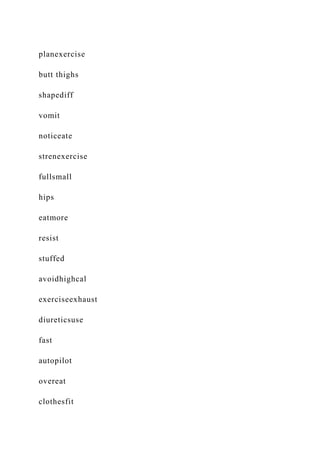

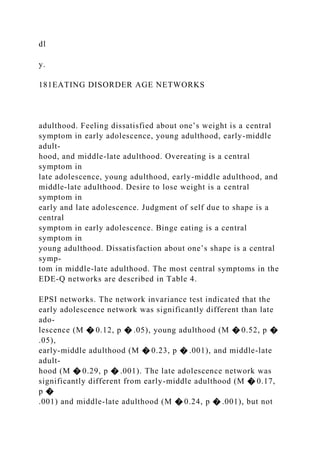

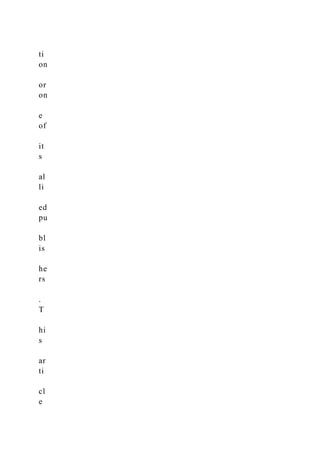

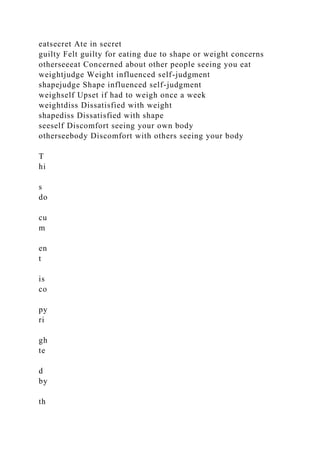

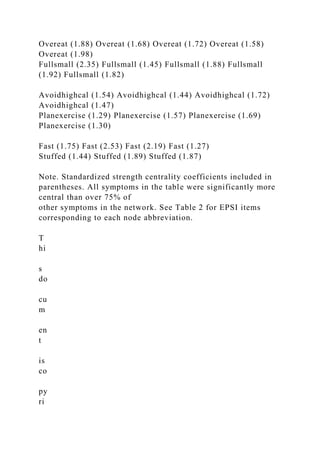

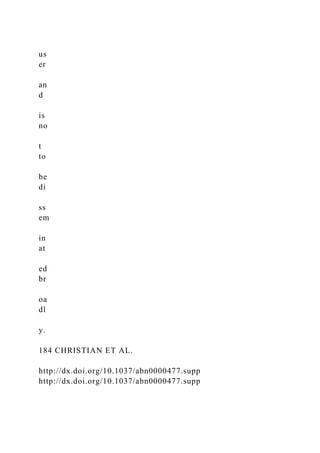

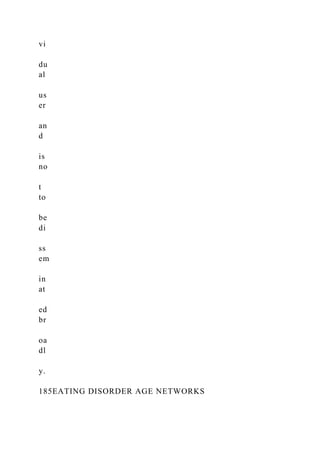

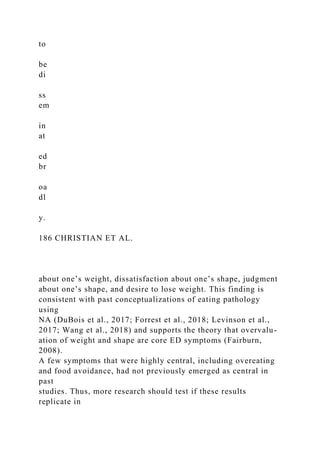

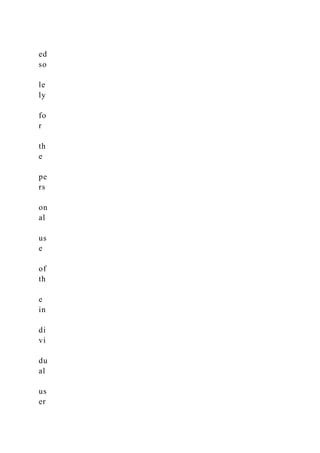

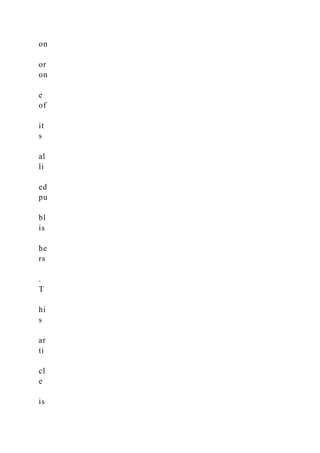

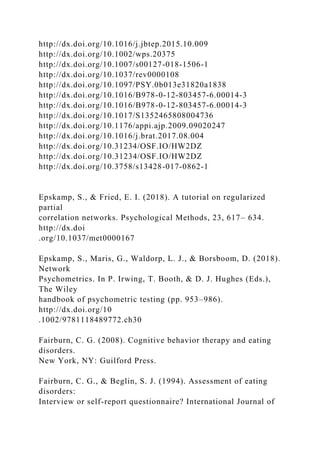

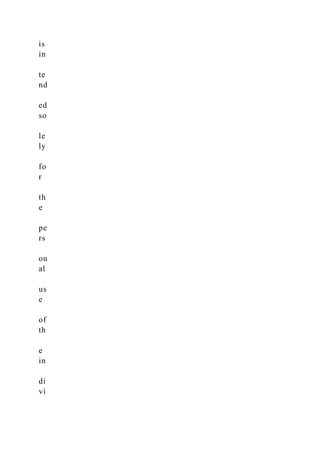

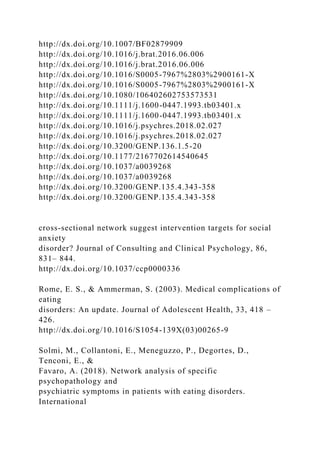

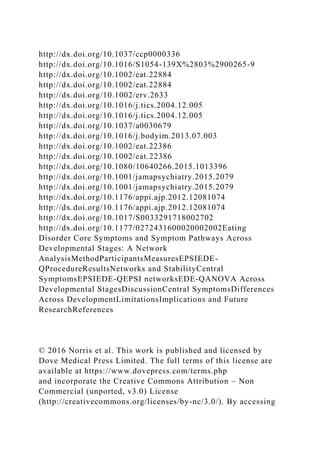

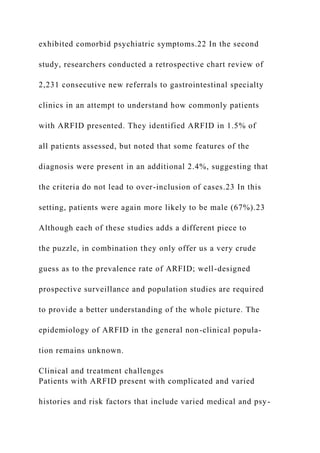

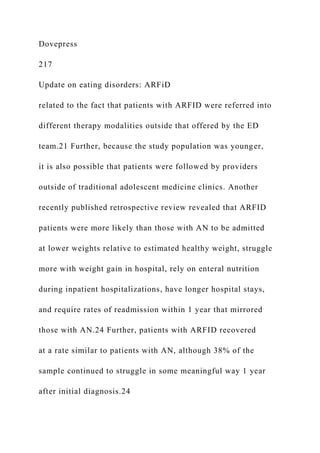

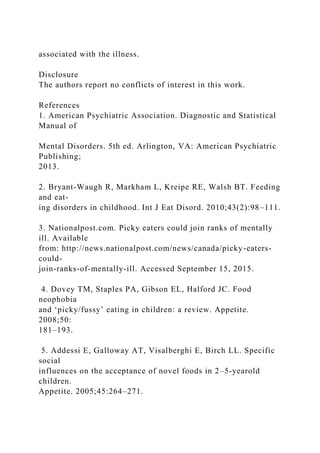

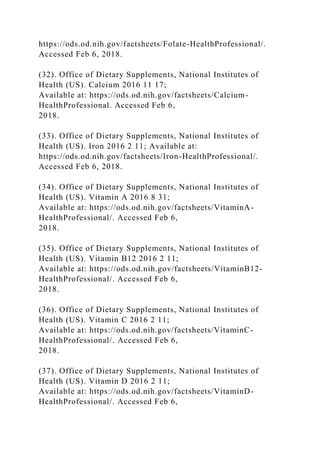

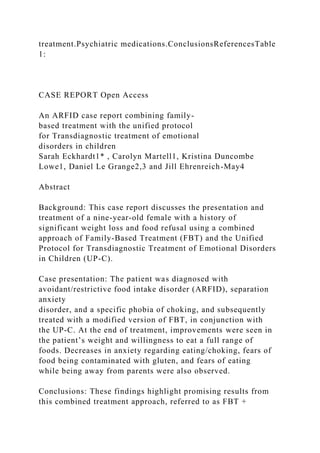

![AN 13 (.9) 85 (.9) 159 (1.4) 133 (1.7) 19 (1.6)

BN 2 (.1) 37 (.4) 99 (.8) 104 (1.3) 12 (1.0)

BED 4 (.3) 12 (.1) 49 (.4) 104 (1.3) 55 (4.6)

Other 3 (.2) 42 (.4) 93 (.8) 102 (1.3) 18 (1.5)

Missing 1501 (98.6) 9662 (98.2) 11309 (96.6) 7522 (94.6) 1090

(91.3)

Duration of illness (M[SD]) 1.71 (1.71) 2.92 (2.27) 5.82 (3.96)

13.86 (8.37) 29.00 (14.60)

EPSI 1028 (100) 6171 (100) 10701 (100) 9929 (100) 2073 (100)

Gender

Female 959 (93.3) 5786 (93.8) 10108 (94.5) 9412 (94.8) 1857

(89.6)

Male 46 (4.5) 228 (3.7) 381 (3.6) 438 (4.4) 201 (9.7)

Missing 23 (2.2) 157 (2.5) 212 (2.0) 79 (.8) 15 (.7)

Diagnosis

AN 152 (14.8) 796 (12.9) 1456 (13.6) 995 (10.0) 172 (8.3)

BN 30 (2.9) 307 (5.0) 870 (8.1) 825 (8.3) 81 (3.9)

BED 31 (3.0) 165 (2.7) 514 (4.8) 1144 (11.5) 527 (25.4)

Other 62 (6.0) 354 (5.7) 795 (7.4) 830 (8.4) 222 (10.7)

Missing 753 (73.2) 4549 (73.7) 7066 (66.0) 6134 (61.8) 1071

(51.7)

Duration of illness (M[SD]) 2.06 (2.11) 3.19 (2.44) 6.05 (4.12)

14.54 (8.58) 29.12 (15.20)

Note. EDE-Q � Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire;

EPSI � Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory; AN � anorexia

nervosa; BN � bulimia

nervosa; BED � binge eating disorder.

T

hi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-71-320.jpg)

![ed

br

oa

dl

y.

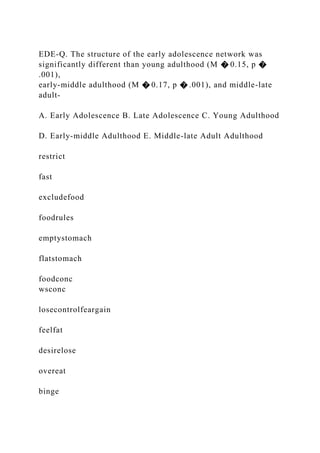

179EATING DISORDER AGE NETWORKS

participants’ gender, ED diagnoses, and duration of illness

across

developmental categories.

Measures

EPSI. The EPSI is a 45-item multidimensional measure de-

signed to assess ED symptoms. The EPSI has eight scales corre-

sponding to unique facets of eating pathology: Body

Dissatisfac-

tion (i.e., satisfaction with body shape and body parts; e.g.,

hips,

thighs), Binge Eating (i.e., tendency to overeat or eat

mindlessly),

Cognitive Restraint (i.e., attempting to restrict eating, whether

successful or not), Excessive Exercise (i.e., intense or

compulsive

exercise), Restricting (i.e., efforts to avoid or reduce eating),

Purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting and laxative/diuretic use),

Muscle Building (i.e., cognitions and behaviors [supplement

use]

related to increasing muscularity), and Negative Attitudes

Toward

Obesity (i.e., negative judgment of individuals who are over-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-76-320.jpg)

![.1080/10640260590932841

Forrest, L. N., Jones, P. J., Ortiz, S. N., & Smith, A. R. (2018).

Core

psychopathology in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A

network

analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 668 –

679. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.22871

Fried, E. I., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2017). Moving forward:

Challenges and

directions for psychopathological network theory and

methodology.

Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 999 –1020.

http://dx.doi.org/

10.1177/1745691617705892

Fulton, C. L. (2016). Disordered eating across the lifespan of

women

[PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-

source/

vistas/disordered-eating.pdf?sfvrsn�769e4a2c_4

Gadalla, T. M. (2008). Eating disorders and associated

psychiatric comor-

bidity in elderly Canadian women. Archives of Women’s Mental

Health,

11, 357–362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00737-008-0031-8

Goldschmidt, A. B., Crosby, R. D., Cao, L., Moessner, M.,

Forbush, K. T.,

Accurso, E. C., & Le Grange, D. (2018). Network analysis of

pediatric

eating disorder symptoms in a treatment-seeking,

transdiagnostic sam-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-164-320.jpg)

![with AN as they lacked

Correspondence: Mark L Norris

Division of Adolescent Medicine,

Department of Pediatrics, Children’s

Hospital of eastern Ontario, University

of Ottawa, 401 Smyth Road, Ottawa,

ON K1H 8L1, Canada

Tel +1 613 737 7600

Fax +1 613 738 4878

email [email protected]

Journal name: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment

Article Designation: Review

Year: 2016

Volume: 12

Running head verso: Norris et al

Running head recto: Update on eating disorders: ARFID

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S82538

http://www.dovepress.com/permissions.php

https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

www.dovepress.com

www.dovepress.com

www.dovepress.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S82538

mailto:[email protected]

Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2016:12submit your

manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-188-320.jpg)

![texture, taste, appearance); a fear

Corresponding author:Kathryn S. Brigham, MD, Division of

Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Massachusetts General

Hospital. 55 Fruit St- Yawkey 6D, Boston, MA 02114,

[email protected]

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Curr Pediatr Rep. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019

June 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Curr Pediatr Rep. 2018 June ; 6(2): 107–113.

doi:10.1007/s40124-018-0162-y.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

A

u

th

o

r M](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-216-320.jpg)

![References

(1). American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric

Association DSM-5 Task Force.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5.

5th ed. ed. Arlington, VA; 2013.

(2). American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric

Association Task Force on DSM.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV.

4th ed. ed. Washington, DC;

1994.

(3). Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T,

Eddy KT. Avoidant/Restrictive Food

Intake Disorder: a Three-Dimensional Model of Neurobiology

with Implications for Etiology and

Treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017 8;19(8):54–017–0795–5.

[PubMed: 28714048]

(4). Fisher MM, Rosen DS, Ornstein RM, Mammel KA,

Katzman DK, Rome ES, et al. Characteristics

of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and

adolescents: a “new disorder” in

DSM-5. J Adolesc Health 2014 7;55(1):49–52. [PubMed:

24506978]

(5). Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating

disorders: current perspectives on

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016 1

19;12:213–218. [PubMed: 26855577]

(6). Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, Hastings E, Edkins K, Lamont E,

Nevins CM, et al. Prevalence of DSM-5

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-250-320.jpg)

![gastroenterology healthcare network. Int J

Eat Disord 2015 7;48(5):464–470. [PubMed: 25142784]

(7). Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AEL, Gonzalez-Chica DA,

Stocks N, Touyz S. Burden and health-

related quality of life of eating disorders, including

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

(ARFID), in the Australian population. J Eat Disord 2017 7

3;5:21-017-0149-z. eCollection

2017.

(8). Kurz S, van Dyck Z, Dremmel D, Munsch S, Hilbert A.

Early-onset restrictive eating disturbances

in primary school boys and girls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry

2015 7;24(7):779–785. [PubMed:

25296563]

Brigham et al. Page 8

Curr Pediatr Rep. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019

June 01.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-251-320.jpg)

![n

u

scrip

t

(9). Forman SF, McKenzie N, Hehn R, Monge MC, Kapphahn

CJ, Mammel KA, et al. Predictors of

outcome at 1 year in adolescents with DSM-5 restrictive eating

disorders: report of the national

eating disorders quality improvement collaborative. J Adolesc

Health 2014 12;55(6):750–756.

[PubMed: 25200345]

(10). Norris ML, Robinson A, Obeid N, Harrison M, Spettigue

W, Henderson K. Exploring avoidant/

restrictive food intake disorder in eating disordered patients: a

descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord

2014 ;47(5):495–499. [PubMed: 24343807]

(11). Ornstein RM, Rosen DS, Mammel KA, Callahan ST,

Forman S, Jay MS, et al. Distribution of

eating disorders in children and adolescents using the proposed

DSM-5 criteria for feeding and

eating disorders. J Adolesc Health 2013 ;53(2):303–305.

[PubMed: 23684215]

(12). Nicely TA, Lane-Loney S, Masciulli E, Hollenbeak CS,

Ornstein RM. Prevalence and

characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a

cohort of young patients in day

treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2014 8 2;2(1):21-

014-0021-3. eCollection 2014.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-253-320.jpg)

![(13). Ornstein RM, Essayli JH, Nicely TA, Masciulli E, Lane-

Loney S. Treatment of avoidant/

restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in

a partial hospitalization program

for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2017 9;50(9):1067–1074.

[PubMed: 28644568]

(14). Mammel KA, Ornstein RM. Avoidant/restrictive food

intake disorder: a new eating disorder

diagnosis in the diagnostic and statistical manual 5. Curr Opin

Pediatr 2017 8;29(4):407–413.

[PubMed: 28537947]

(15). Thomas JJ, Brigham KS, Sally ST, Hazen EP, Eddy KT.

Case 18-2017 - An 11-Year-Old Girl

with Difficulty Eating after a Choking Incident. N Engl J Med

2017 6 15;376(24):2377–2386.

[PubMed: 28614676]

(16). Marild K, Stordal K, Bulik CM, Rewers M, Ekbom A, Liu

E, et al. Celiac Disease and Anorexia

Nervosa: A Nationwide Study. Pediatrics 2017

5;139(5):10.1542/peds.2016-4367. Epub 2017

Apr 3.

(17). De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, Misra M, Williams NI,

Mallinson RJ, et al. 2014 Female Athlete

Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return

to Play of the Female Athlete

Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco,

California, May 2012 and 2nd

International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May

2013. Br J Sports Med 2014 2;48(4):

289-2013-093218.

(18). Setnick J Micronutrient deficiencies and supplementation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-254-320.jpg)

![in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a

review of literature. Nutr Clin Pract 2010 ;25(2):137–142.

[PubMed: 20413694]

(19). Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, Golden NH,

Katzman DK, Sawyer SM, Ornstein

RM, Rome ES, et al. Position Paper of the Society for

Adolescent Health and Medicine: medical

management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and

young adults. J Adolesc Health

2015 1;56(1):121–125. [PubMed: 25530605]

(20). Bryant-Waugh R, Micali N, Cooke L, et al. The Pica,

ARFID, and Rumination Disorder

Interview: Development of a multi-informant, semi-structured

interview of feeding disorders

across the lifespan. In preparation

(21). Hilbert A, van Dyck Z. Eating Disorders in Youth-

Questionnaire. English version . 2016 6 21;

Available at: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:15-qucosa-

197246. Accessed Feb 28, 2018.

(22). Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the Nine Item

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake

disorder screen (NIAS): A measure of three restrictive eating

patterns. Appetite 2018 4 1;123:32–

42. [PubMed: 29208483]

(23). Strandjord SE, Sieke EH, Richmond M, Rome ES.

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder:

Illness and Hospital Course in Patients Hospitalized for

Nutritional Insufficiency. J Adolesc

Health 2015 12;57(6):673–678. [PubMed: 26422290]

(24). Brown J, Kim C, Lim A, Brown S, Desai H, Volker L, et](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-255-320.jpg)

![al. Successful gastrostomy tube weaning

program using an intensive multidisciplinary team approach. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014

6;58(6):743–749. [PubMed: 24509305]

(25). Sharp WG, Stubbs KH, Adams H, Wells BM, Lesack RS,

Criado KK, et al. Intensive, Manual-

based Intervention for Pediatric Feeding Disorders: Results

From a Randomized Pilot Trial. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016 4;62(4):658–663. [PubMed:

26628445]

Brigham et al. Page 9

Curr Pediatr Rep. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019

June 01.

A

u

th

o

r M

a

n

u

scrip

t

A

u

th

o](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-256-320.jpg)

![http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:15-qucosa-197246

(26). Sant’Anna AM, Hammes PS, Porporino M, Martel C,

Zygmuntowicz C, Ramsay M. Use of

cyproheptadine in young children with feeding difficulties and

poor growth in a pediatric feeding

program. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014 11;59(5):674–678.

[PubMed: 24941960]

(27). Thomas J, Eddy K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder:

Children, adolescents, and adults Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press; In press 2018.

(28). Kardas M, Cermik BB, Ekmekci S, Uzuner S, Gokce S.

Lorazepam in the treatment of

posttraumatic feeding disorder. J Child Adolesc

Psychopharmacol 2014 6;24(5):296–297.

[PubMed: 24813692]

(29). Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive Use of

Olanzapine in the Treatment of Avoidant

Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in Children and Adolescents in

an Eating Disorders Program. J

Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2017 12;27(10):920–922.

[PubMed: 29068721]

(30). Mueller C editor. The ASPEN Adult Nutrition Support

Core Curriculum 3rd ed. Silver Spring,

MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition;

2017.

(31). Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of

Health (US). Folate 2016 4 20; Available at:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-258-320.jpg)

![UP for ARFID. Further research is needed to evaluate the use of

this treatment in patients presenting with a variety of

ARFID symptoms.

Keywords: Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, Emotional

disorders, Family-based treatment, Unified protocol,

Transdiagnostic

Background

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), a com-

plex and heterogeneous diagnosis, has been hypothesized

along a dimensional model with presentations including

sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive consequences, and lack

of interest in eating [1, 2]. Significant literature exists on

the treatment of pediatric feeding disorders supporting the

use of behavioral feeding interventions among young chil-

dren [3]. Recently, individual case reports/series have sug-

gested other promising approaches for older children,

adolescents, and adults with ARFID, using as a base either

family-based treatment (FBT) [4–7];, cognitive behavioral

therapy (CBT) [8–10];, or other novel approaches [11].

Despite these new approaches being studied, no published,

randomized controlled trials have yet to evaluate their effi-

cacy for the treatment of ARFID [2]. What appears to be

lacking in the current treatment models is the ability to

concurrently address the high rates of comorbid mood

and anxiety disorders in patients with ARFID [12, 13],

while also remaining focused on the medical complica-

tions associated with those patients who present under-

weight or exhibit significant nutritional deficiencies as

part of this diagnosis. Consequently, this case presentation

proposes a novel treatment approach that attempts to ad-

dress both the psychological and emotional comorbidities

associated in children and adolescents with ARFID, as well

as the hallmark food avoidance features that appear across](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-268-320.jpg)

![a heterogeneous array of presentations.

This case study describes the treatment of a patient

with ARFID, using a combined approach of FBT [14]

and the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment

of Emotional Disorders in Children (UP-C) [15]. FBT +

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were

made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to

the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

* Correspondence: [email protected]

1Center for the Treatment of Eating Disorders, Children’s

Minnesota,

Minneapolis, MN, USA

Full list of author information is available at the end of the

article

Eckhardt et al. Journal of Eating Disorders (2019) 7:34

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-019-0267-x

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1186/s40337-019-

0267-x&domain=pdf

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0824-4328

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

mailto:[email protected]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-269-320.jpg)

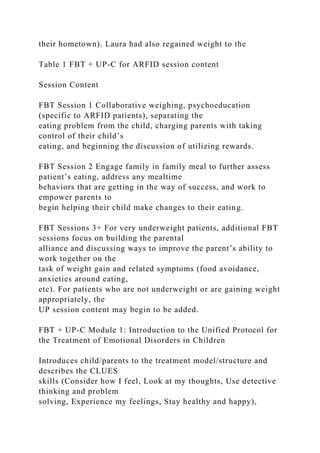

![UP for ARFID was developed through a 3 year case

consultation process with treatment developers of both

FBT and the UP-C. Treatment focuses on a combination

of techniques aimed at addressing both weight gain/

normalization of eating and additional symptoms includ-

ing fear, disgust, and worry or obsessive thoughts, as

well as varying forms of functionally-related avoidance

behavior and potential concomitant reinforcement of

avoidance by parents/caregivers. A major advantage of

this combined approach is that it allows the clinician to

personalize treatment based on the patient’s specific

presentation using a core set of evidence-based strategies

and assessment tools (e.g., Top Problems [16];). The

UP-C is transdiagnostic by definition, and contains

evidence-based strategies that are flexible enough to

address many of the maintaining symptoms that are

unique to ARFID. There is also an adolescent version of

the UP-C, which when combined with FBT makes this

treatment model acceptable for a wide range of patients

(named the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treat-

ment of Emotional Disorders in Adolescents; UP-A).

The UP for adults has previously been adapted for use

with other eating disorder populations (anorexia nervosa,

bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder), with early

results indicating improvments in anxiety sensitivity, ex-

periential avoidance, and mindfulness [17].

While flexible, FBT + UP for ARFID always begins with

sessions focused on FBT principles, including collabora-

tive weighing, psychoeducation (specific to ARFID pa-

tients and their eating problems), family engagement,

separating the eating problem from the child, charging

parents with taking control of their child’s eating (includ-

ing increasing volume and variety of foods), promoting

weight gain as needed, and a family meal. The UP-C or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-270-320.jpg)

![UP-A is then added to build skills that empower the

patient to cope with difficult emotions, address avoidance,

and increase tolerance of emotions or disgust responses.

The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of

Emotional Disorders (UP) [18] is an emotion-focused,

evidence-based treatment that targets the core dysfunction

of neuroticism in adults [19]. It has subsequently been

adapted to address emotional disorders in youth with the

development of the Unified Protocols for Transdiagnostic

Treatment of Emotional Disorders in Children and Ado-

lescents (UP-C and UP-A respectively [15];). These proto-

cols bring together cognitive-behavioral techniques, such

as cognitive reappraisal, problem-solving and opposite

action strategies, including a variety of exposure para-

digms and behavioral activation, as well as mindfulness

techniques into a single treatment. The UP-C and UP-A

present the same skills as the UP; however, the skills have

been adapted to be developmentally sensitive in their

presentation, as well as in their delivery. Furthermore, the

UP-C and UP-A also target core emotional parenting

behaviors that are common across emotional disorders in

youth (i.e. high levels of criticism, over-control/over

protection, inconsistency, and modeling of avoidance

[15]). Research has provided support for the efficacy and

feasibility of the UP, UP-A and UP-C for individuals with

mood, anxiety, and other emotional disorders. The UP,

in particular, has been shown to lead to significant

improvements at post-treatment [20], as well as main-

tenance of gains at follow-up time points [21] . The

UP-C was originally designed as a group version of the

UP-A, with concurrent child and parent group content.

However, the UP-C may be delivered in an individual

therapy model and explicit directions for doing so are

presented in the therapist guide. Preliminary evidence

suggests the UP-C may be similarly effective to leading](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-271-320.jpg)

![CBT approaches for childhood anxiety, with potential

benefits for those youth with higher levels of parent-

reported sadness, dysregulation or depressive symptoms

[22, 23]. The UP-A has also been shown to improve

symptoms of emotional disorders in adolescents. Re-

sults from multiple baseline, open-trial and initial wait-

list controlled trial studies showed that adolescents

evidenced significant improvement in their symptoms

after receiving 16 sessions of treatment using the UP-A

and gains were maintained at follow-up time points

[24–26]. While results of initial patient outcomes for

this combined FBT + UP for ARFID approach are not

yet available (given this treatment is currently being

studied as part of a larger, clinic-wide effectiveness

study), feedback from individual patients and practi-

tioners who have been trained in the model through a

clinical teaching day at the Academy of Eating Disor-

ders International Conference has been positive [27].

Consent to share the following case was provided by

the family and patient. Changes in identifying informa-

tion were made to protect patient privacy.

Case presentation

“Laura” is a nine-year-old female, who presented with 38

lbs. of weight loss, poor oral intake, and medical instability

in the context of fears about eating/choking secondary to

a recent diagnosis of gluten intolerance. Ten months be-

fore she presented for treatment, Laura felt unwell after

eating at a restaurant with her family. Following this ex-

perience, she became more anxious with eating, reporting

frequent stomach aches and headaches. Laura’s family

tried a variety of elimination diets, including stopping all

dairy and gluten. Laura was seen multiple times by her

pediatrician, who ultimately recommended allergy and

celiac testing. Over the course of this time Laura lost 29%

of her overall body weight. Laura’s symptoms continued](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-272-320.jpg)

![ation anxiety. Given Laura had previously trended at or

above the 85th percentile for BMI, the goal was to return

her weight back to her personal healthy weight range.

The underlying assumption of FBT + UP for ARFID is

that patients diagnosed with ARFID need a combination

of treatment techniques that focus on both weight gain

and/or normalizing eating while also addressing add-

itional emotional disorder symptoms (i.e. anxiety, de-

pression, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, emotional/

situational avoidance). Patients and their parents begin

with traditional FBT for several sessions (see Table 1 for

content). Once progress with weight gain/regular eating

are underway, the UP-C or UP-A modules are intro-

duced. The UP-C has a flexible approach with core

evidence-based principles and concurrent parenting

content for emotional disorders that can be individual-

ized for specific ARFID presentations [15]. Once the

UP-C is added, the session breakdown continues as

follows: 5 min weigh-in and update from patient on how

eating is progressing, 30–40 min of individual therapy

with the patient focused on the UP-C content, and 10–

15 min with the patient and family to review session

content, discuss how eating/weight gain are progressing,

brainstorm challenges related to eating, and review

homework/exposure practice. For younger patients,

parents may be present for more/all of the session.

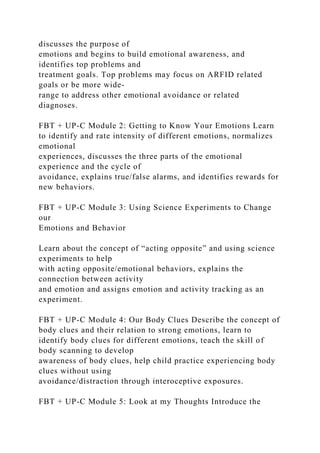

As illustrated in Table 2, over the course of treatment

Laura’s weight increased from 36.7 kg to 44.7 kg (percent

goal weight from 81.4 to 91.4%), with family noting

significant improvements in energy level and ability to

participate in school and other physical activities. During

initial FBT sessions, the focus was on weight gain using

foods that Laura felt were safe and could allow her to re-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-274-320.jpg)

![gain weight efficiently. In session two, a family meal was

completed, where the therapist worked to separate the

illness from Laura and decrease blame (see FBT manual

[14]), as well as discuss rewards that could be utilized to

encourage Laura to challenge herself with eating. After

two sessions of FBT (and with Laura’s weight increas-

ing), the UP-C was added to sessions, though the focus

of each subsequent session also remained on weight

regain and parental support/empowerment. Of note,

Laura’s family took to the principles of FBT quickly, but

continued to benefit from each session’s focus on graph-

ing the patient’s weight, problem solving any challenges

during weeks where weight was stable or down, and

empowering parents to work closely together on how to

best refeed their daughter.

The patient and family identified three Top Problems

(an ideographic assessment tool by Weisz et al. [16]

modified for use in the UP-C and UP-A by Ehrenreich-

May et al. [15]) they wanted to address in treatment

including: 1) decrease fears of choking/eating feared

foods, 2) be away from/eat away from mother, and 3)

patient sleeping in her own bed again. Additionally, the

therapist reinforced an overarching goal of Laura return-

ing to a healthy weight range as crucial for her recovery.

All subsequent treatment sessions involved reviewing

Laura’s weight/eating, teaching content from the UP-C

modules, and discussing home learning assignments.

As treatment progressed and the patient learned skills

to better manage her emotions, she became more willing

to try foods that she was avoiding. With the help of the

treating clinician, Laura created an exposure hierarchy

with numerous feared foods and situations (e.g. meats,

pasta, nuts, eating with adults other than her mother,

eating at restaurants, being away from her mother, and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-275-320.jpg)

![and decrease anxiety about eating/being away from her

mother. Notably, when this family returned for a follow-

up 5 months after completing treatment, the patient’s

weight had continued to increase (50.4 kg/81st percentile

for BMI/97.1% of goal weight), she had started menstru-

ating, and she was able to separate and eat apart from

her mother without significant difficulty. The patient

and parents also rated her fears of choking and eating

previously feared foods as 1 and 2’s on an 8-point likert

scale (see Table 2).

This patient was a good treatment candidate for FBT +

UP for ARFID given she endorsed significant anxiety prior

to treatment and also met criteria for several concurrent

anxiety disorder diagnoses. Another major benefit of the

treatment is the ability to flexibly offer the various modules

that may benefit each patient based on their specific needs

and ARFID presentations. For example, this patient bene-

fited from exposure work, learning non-judgmental aware-

ness, and improving awareness of physical sensations,

while other patients may need more focus on cognitive

reappraisal, problem-solving, and other types of opposite

action [15]. Additionally, given Laura had lost a significant

amount of weight she required a treatment that also

focused on weight restoration as one of its core principles.

A major advantage of this combined treatment approach is

the ability for clinicians to tailor each session to the specific

needs of their individual patient, including returning to

solely FBT sessions if weight gain or nutritional dificiencies

are not progressing appropriately.

While several novel approaches for the treatment of

ARFID have been suggested [7, 10, 11], randomized con-

trol trials have yet to be presented regarding their effi-

cacy. Even with some intervention research aiming to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-281-320.jpg)

![address the heterogeneous symptoms of ARFID, no

treatment to date has proposed a model that addresses

both the varied presentations of ARFID, as well as its full

range of common comorbid disorders, in one cohesive

approach that is flexible and adaptable to the individual.

While the development of symptom specific treatment

approaches to ARFID is logical, it does not address the

heterogeneous nature of this disorder and can impede

dissemination [28]. With so many different presentations

of ARFID and high rates of comorbid disorders, one

clear treatment that can be used flexibly to adapt to the

range of ARFID presentations and co-occurring disorders

would provide an efficient and cohesive approach to treat-

ing youth with ARFID. Further examination of FBT + UP

for a wide-range of ARFID presentations among youth

continues. A study to establish an ideal combination of

FBT and UP strategies for youth with ARFID between the

ages of 6–18 years, and the preliminary efficacy of this ap-

proach, is a next logical step in this research.

Finally, some limitations with this case study should

be noted. First, it was not possible to ascertain whether

FBT in isolation would have worked as effectively for

this patient as this combined FBT + UP-C approach.

While anxiety reduction has been shown in nutritional-

based therapies, such as FBT, it is unclear if patients

with profound phobic and other concurrent anxiety

would benefit as greatly without specific skills and expos-

ure work inherent in the UP-C. Additional limitations of

this case study include the absence of objective assessment

of psychological outcomes. That said, this young person

made significant improvements in terms of weight, both at

completion of treatment and at follow-up. Moreover, Top

Problems rating by both the patient and parents also

appear to indicate meaningful improvements in a variety of

behavioral domains. However, without objective measures](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-282-320.jpg)

![25. Ehrenreich JT, Goldstein CR, Wright LR, Barlow DH.

Development of a

unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in

youth. Child

Family Behav Ther. 2009;31(1):20–37.

26. Queen AH, Barlow DH, Ehrenreich-May J. The trajectories

of adolescent

anxiety and depressive symptoms over the course of a

transdiagnostic

treatment. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(6):511–21.

27. Lesser JK, Eckhardt S, Le Grange D, Ehrenreich-May J.

Integrating family

based treatment with the unified protocol for the transdiagnostic

treatment

of emotional disorders: A novel treatment for avoidant

restrictive food

intake disorder. Prague: Academy of Eating Disorders

International

Conference; 2017. [Clinical teaching day]

28. McHugh RK, Barlow DH. The dissemination and

implementation of

evidence-based psychological treatments: a review of current

efforts. Am

Psychol. 2010;65(2):73.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations.

Eckhardt et al. Journal of Eating Disorders (2019) 7:34

Page 7 of 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpswww-221015083550-d2f85022/85/httpswww-nationaleatingdisorders-orglearnby-eating-disordera-docx-292-320.jpg)