The 30 June 2019 local elections in Albania took place in a context of deep political polarization and crisis. The main opposition parties boycotted the elections and called on voters to abstain. As a result, many mayoral races were uncontested. The elections suffered from a lack of trust in the impartiality of the election administration due to its unbalanced composition. While voting and counting were carried out efficiently on election day, the broader process failed to provide voters with a genuine choice between political alternatives. The elections did not resolve the underlying political disputes and the country remained in a state of political uncertainty.

![34 This includes citizens convicted of certain crimes or

deported, even in the absence of a final court decision, from

an EU member state, Australia, Canada and the United States,

as well as those under an international warrant.

35 This includes the president, high state officials, judges,

prosecutors, military, national security and police staff,

diplomats and members of election commissions.

36 In 2013 and 2015, the CEC rejected the registrations of

Civil Party of Albania and Shkoder 2015 Party that did

not provide final court decisions on their registrations as

political parties.

37 The Electoral Code does not specify how the period of six-

months tenure in parliament, council or mayor post

should be calculated, which facilitated the CEC’s circumventing

of this requirement. The CEC registered the DCP

as a parliamentary party on the basis of certificates issued by

parliament that defined the six-month period

backwards from the anticipated expiry of mandates of two DCP-

affiliated MPs in 2021. The ECtHR requires

eligibility conditions “to comply with a number of criteria

framed to prevent arbitrary decisions. […t]he

discretion enjoyed by the body concerned must not be

exorbitantly wide; it must be circumscribed, with sufficient

precision, by the provisions of domestic law”. See Podkolzina

v. Latvia case (application no. 46726/99, 6 July

2002), paragraph 35.

http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-60417

Republic of Albania Page: 11

Local Elections, 30 June 2019](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-36-2048.jpg)

![broadcaster should not be accessible to people with clear

political affiliation.

B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution and legislation provide for freedom of

expression and prohibit censorship. Contrary

to previous ODIHR recommendations, defamation remains a

criminal offense, punishable with fines

up to ALL 3 million. Moreover, the proposed amendments to the

Law on Audiovisual Media and the

Law on Electronic Communications, approved and released for

public scrutiny by the government on

62 The OSCE Representative on the Freedom of the Media

(RFOM) concluded that the amendments “could in the

long term very negatively impact media plurality and therefore

media freedom in Albania”. The 2009 Declaration

of UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and

Expression (RFOE) and the OSCE RFOM calls states to

“put in place a range of measures, including […] rules to

prevent undue concentration of media ownership”.

63 According to the National Business Centre, the Hoxha

family owns 100 per cent of Top Channel and some 51 per

cent of DigitAlb. The latter owns 100 per cent of ADTN. Each

company holds one national license. Article 62.4

of the Law on Audio-Visual Media prohibits any physical or

legal person who owns a national license from

owning more than 20 per cent of a company that holds another

national license.

64 Six members are nominated by the ruling majority and five

by the opposition.

65 According to the RTSH, during 2018 some 30 per cent of its](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-54-2048.jpg)

![that the amendments could “increase [the level] of censorship

and self-censorship in the local media and could

contribute to further setbacks on media freedom and freedom of

expression in Albania”. On 15 August, the

President issued a statement expressing his concerns over the

government-proposed anti-defamation draft law.

See also the statement and the legal review of the OSCE RFOM.

70 On 30 May, the CEC provided the SP with 60 minutes, SDY

with 30 minutes, all other non-parliamentary parties

contesting the elections with 10 minutes and independent

candidates with 5 minutes of free airtime on the RTSH.

71 The Electoral Code limits the amount of paid airtime for

each private broadcaster for the campaign to 90 minutes

for parliamentary and 10 minutes for non-parliamentary parties

and independent candidates. The 2007 Council of

Europe’s Committee of Ministers Recommendation

CM/Rec(2007)15 recommends to all participating states that

their “regulatory frameworks […] ensure that all contending

parties have the possibility of buying advertising

space on and according to equal conditions and rates of

payment”.

72 In these pricelists, most media outlets also offered pay-for

space in news and current affairs programmes.

73 Some media outlets informed the ODIHR EOM that the free

airtime was provided to the DCP as it did not have

sufficient resources to pay for advertisements. Some of these

media did not submit pricelists to the CEC.

74 The CEC did not approve the MMB’s 3 June request to

recruit more staff to monitor a larger sample.

75 Paragraph 7.8 of the 1990 OSCE Copenhagen Document

requires the participating States to “Provide that no legal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-58-2048.jpg)

![members of election administration, political parties’ standing

in cases challenging other contestants’ registration,

candidate registration, rejection of candidate withdrawal

requests and the location of voting centres.

89 In its 9 May decision on the appeal against registration of

the DCP, the Electoral College found that the

complainant Albanian Democrat Union Party and other

contestants have no legitimate interest in challenging the

legality of registration of other contesting parties and therefore

cannot appeal relevant CEC decisions. Section

3.3.f of the 2002 Venice Commission Code of Good Practice in

Electoral Matters recommends that “All

candidates […] registered in the constituency concerned must be

entitled to appeal”.

Republic of Albania Page: 22

Local Elections, 30 June 2019

ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report

June, the Electoral College rejected the appeal against this CEC

decision also ruling the 10 June

presidential decree as invalid.90

Some ODIHR EOM interlocutors expressed concerns about the

CEC’s lack of impartiality, pointing

to instances in which majority of CEC members voted along

party lines.91 While the Electoral College

judges enjoy immunity and cannot be subject to disciplinary

proceedings during the entire term for

which the College is constituted, they are subject to the ongoing

“vetting process”, which could affect

the security of their tenure and thereby potentially impact their

independence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-71-2048.jpg)

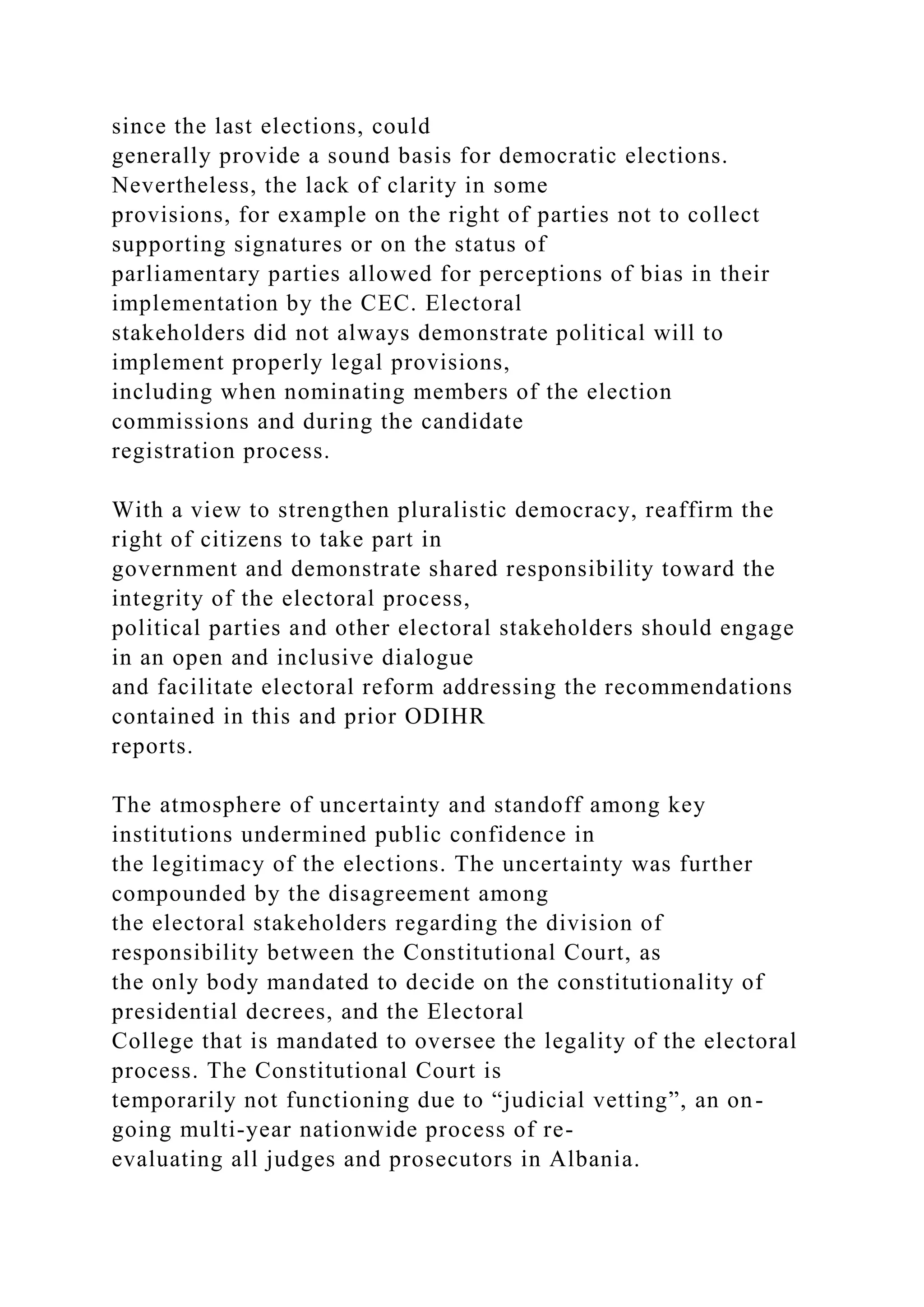

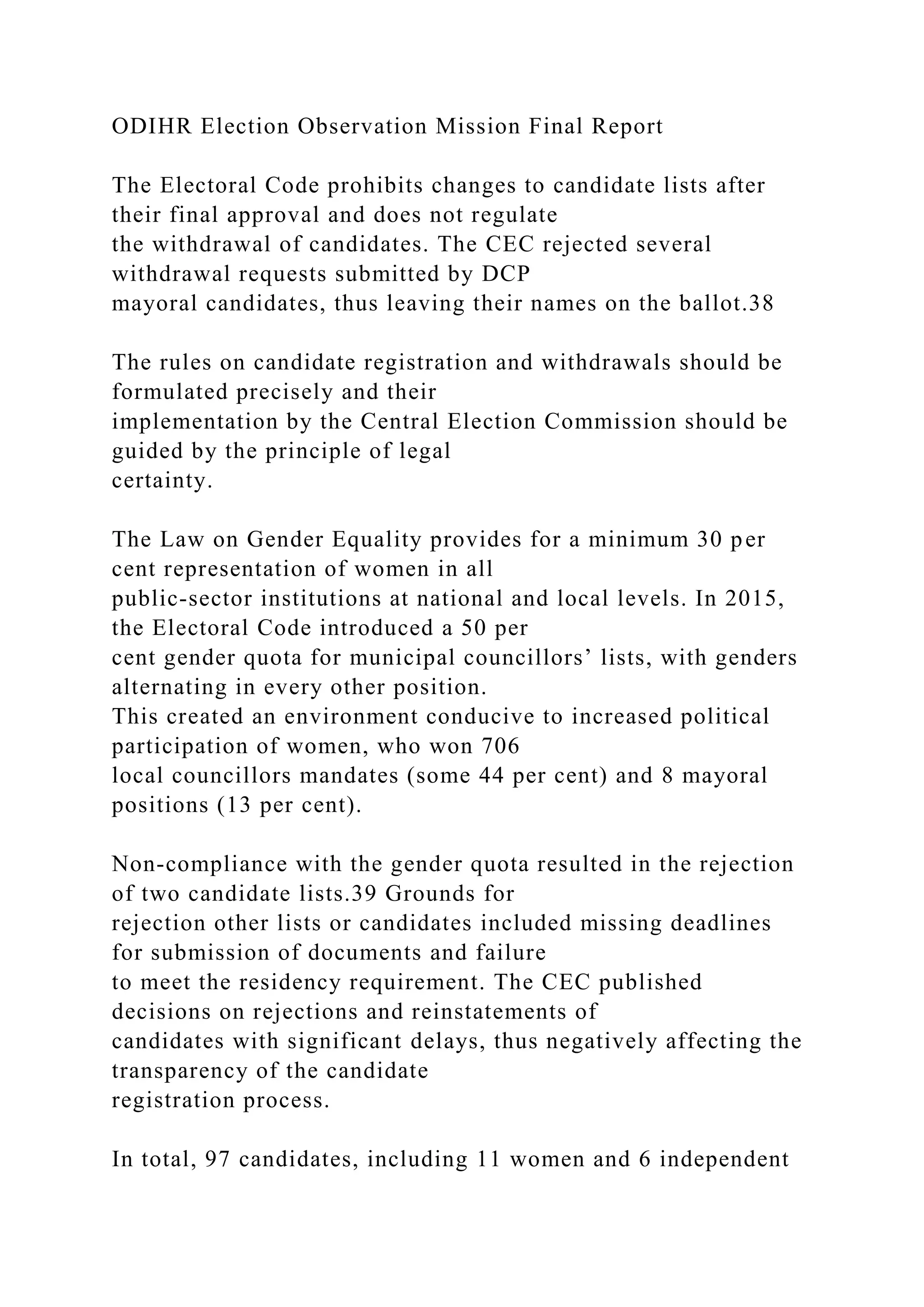

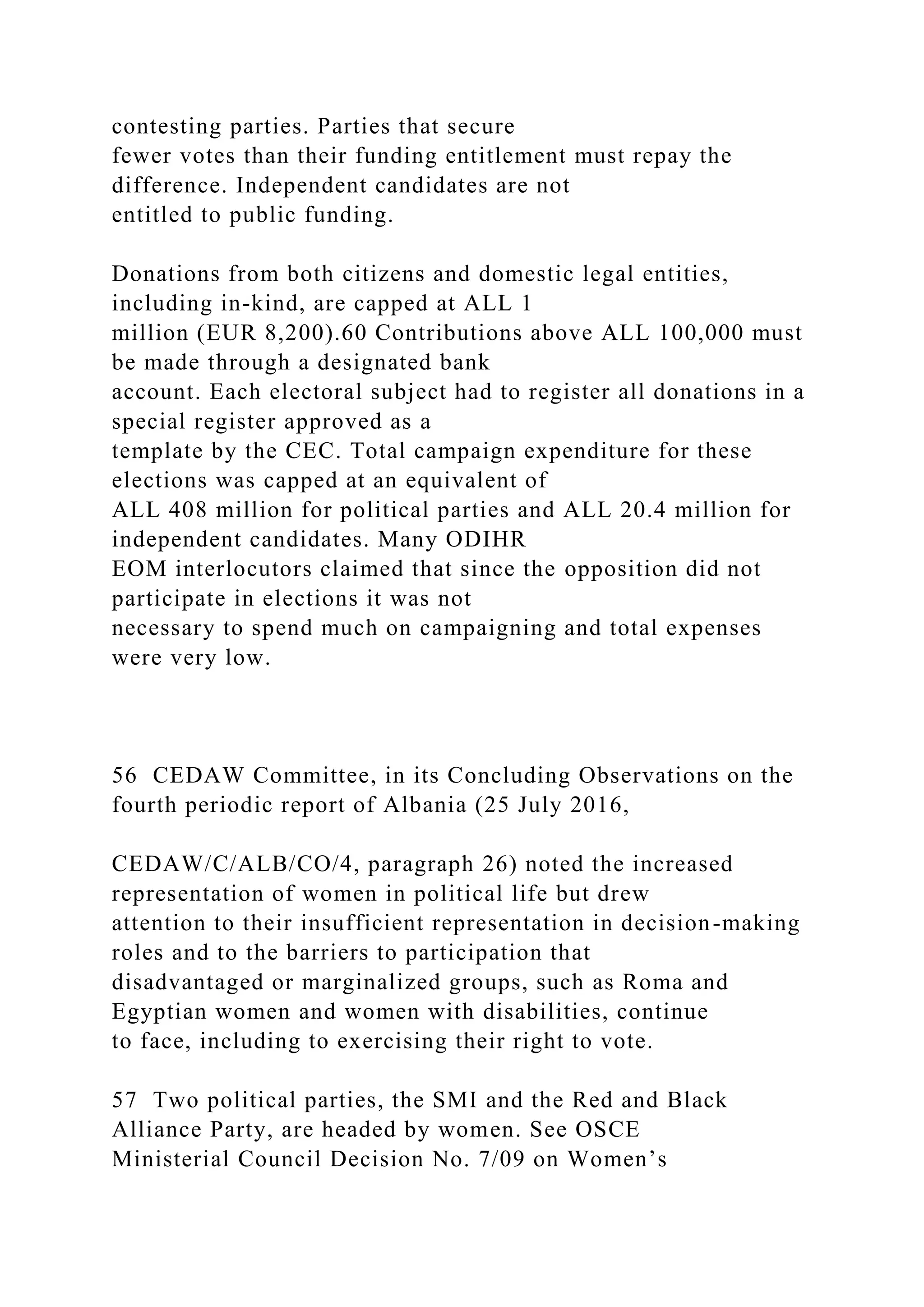

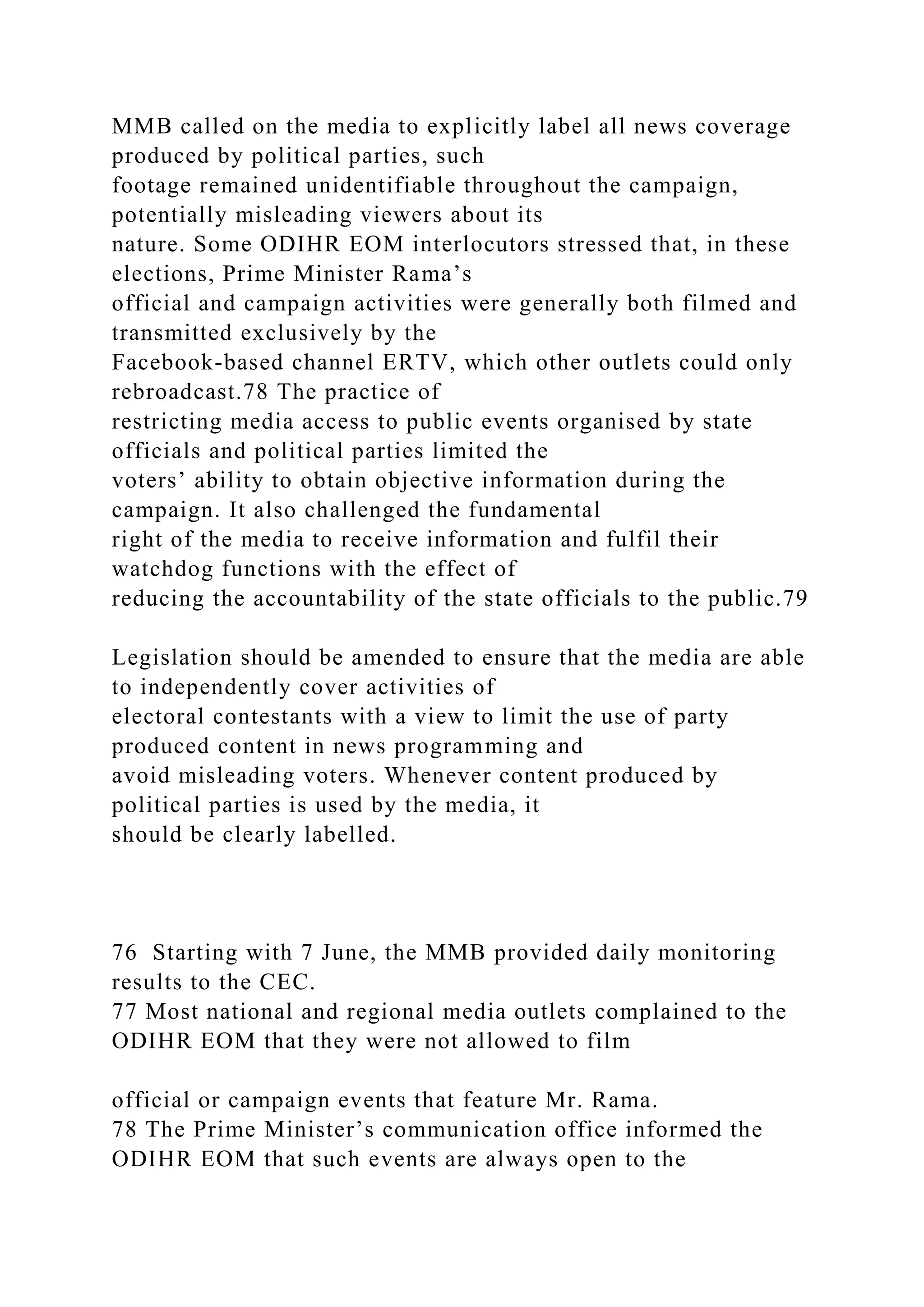

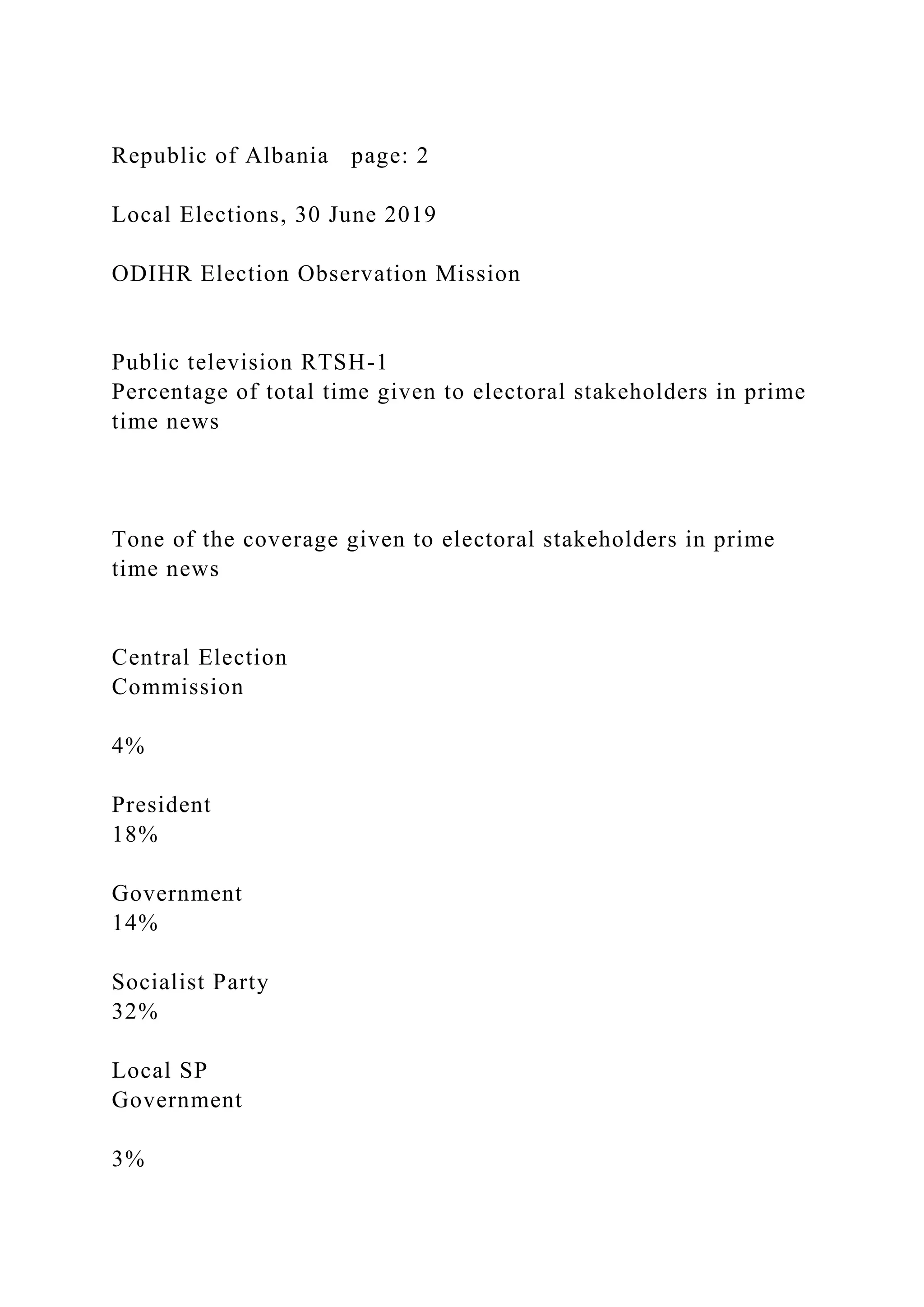

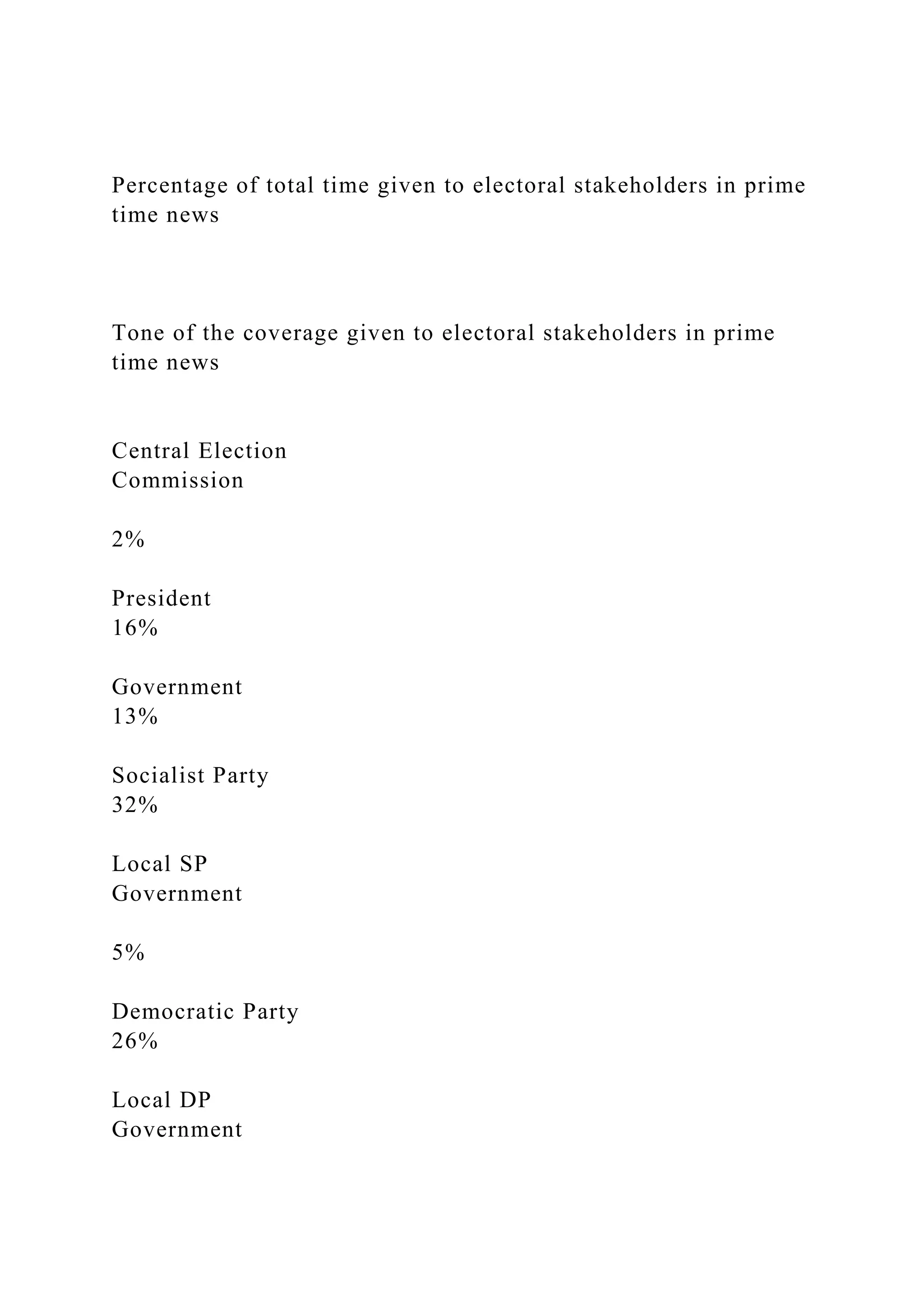

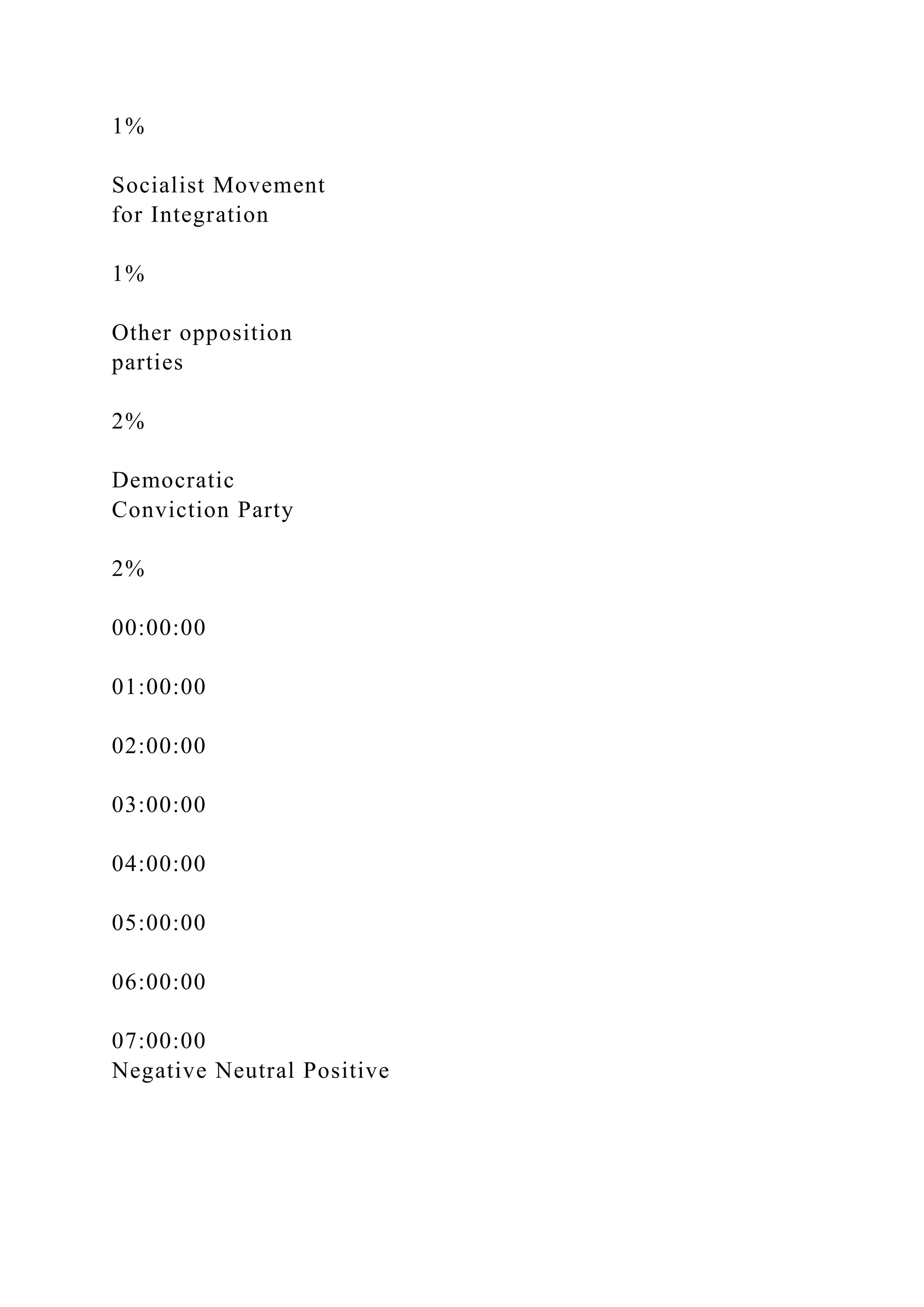

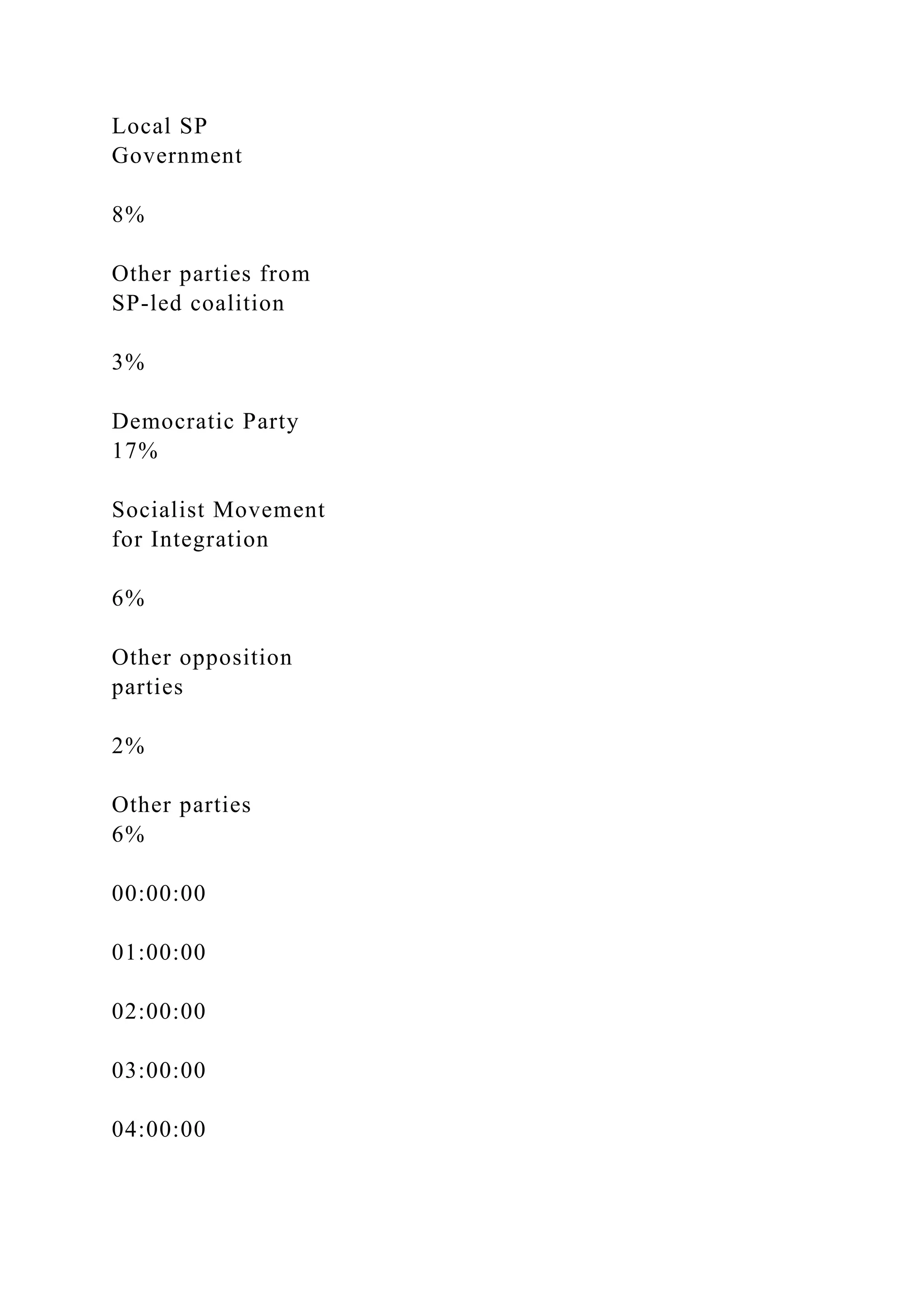

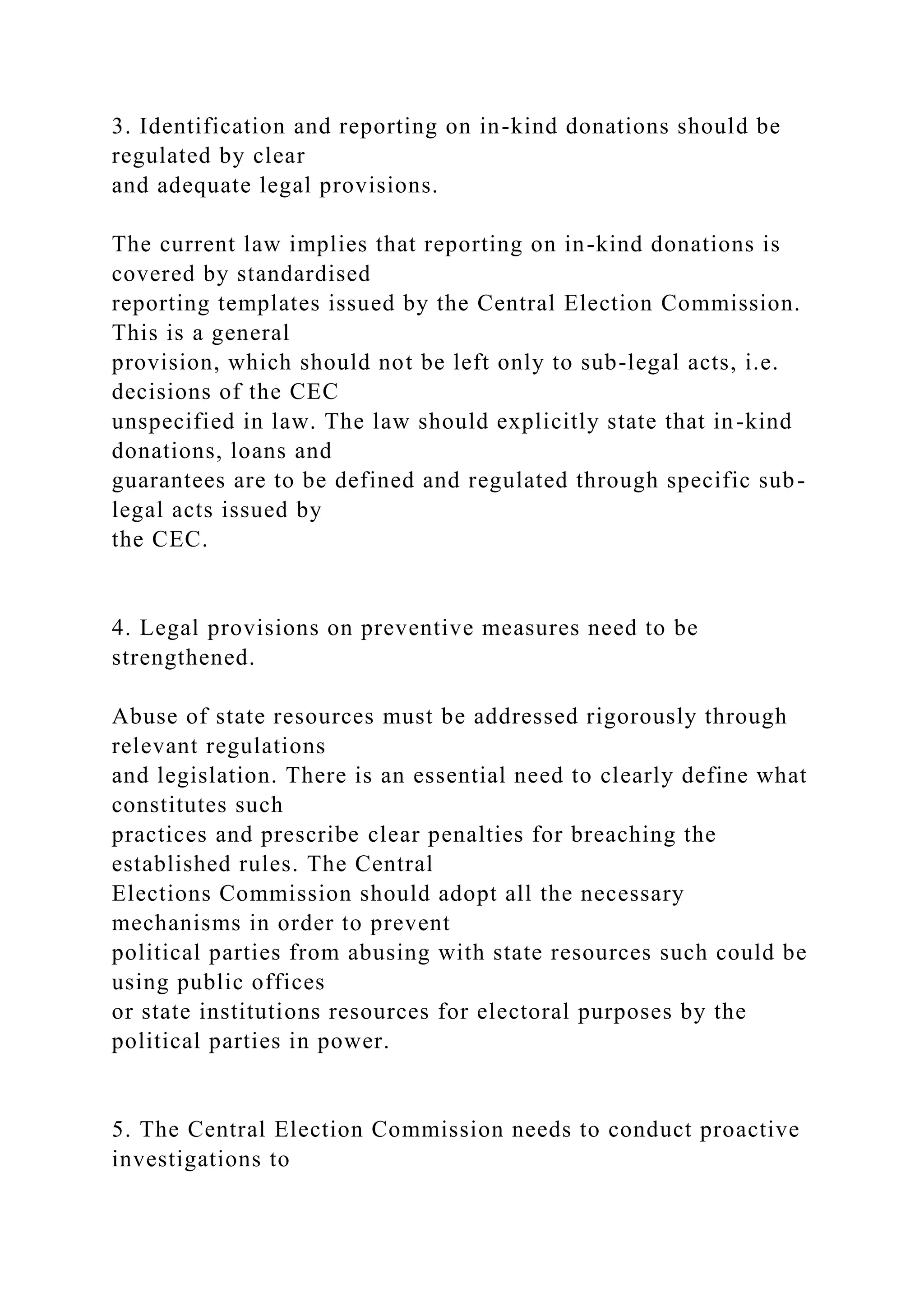

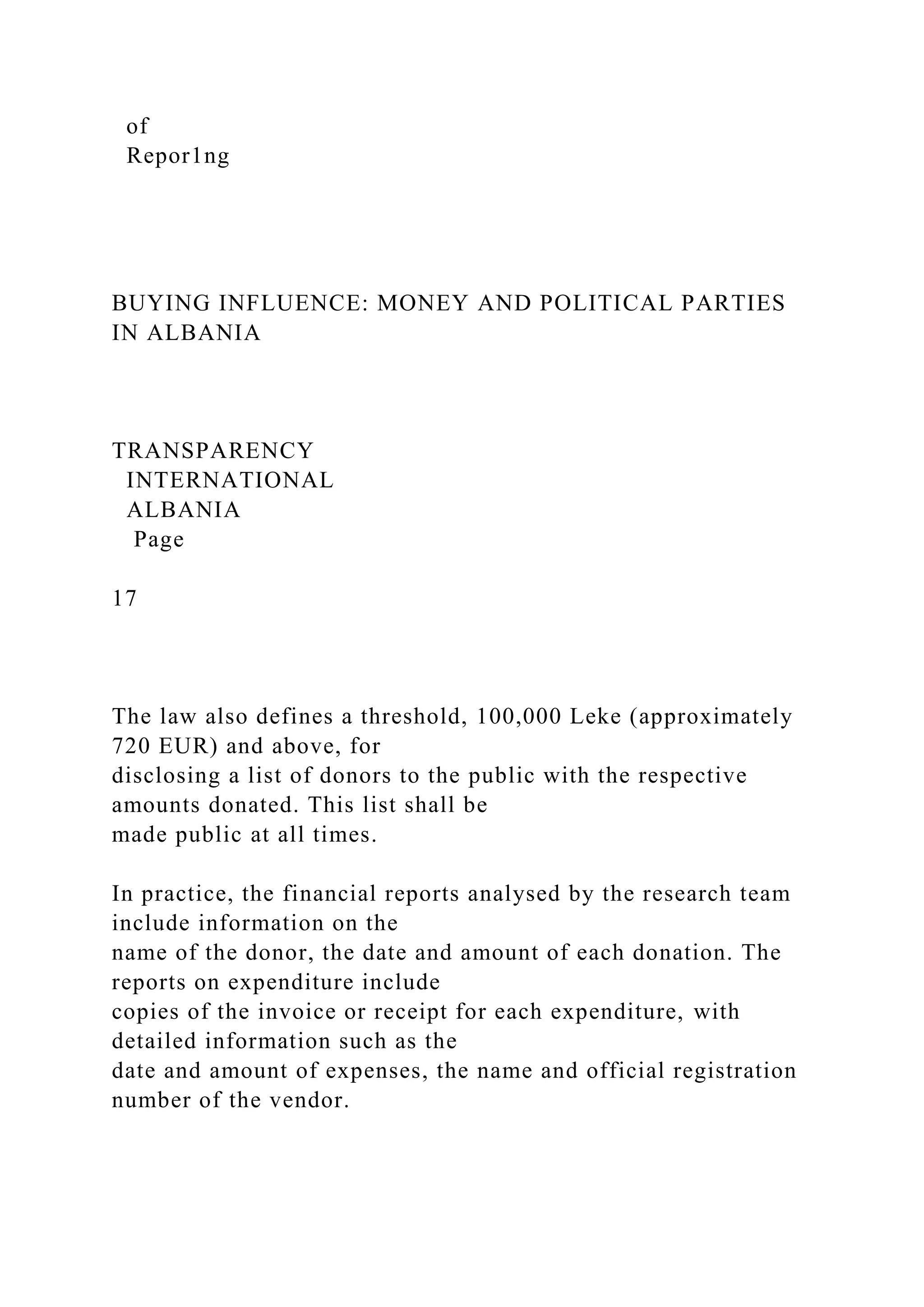

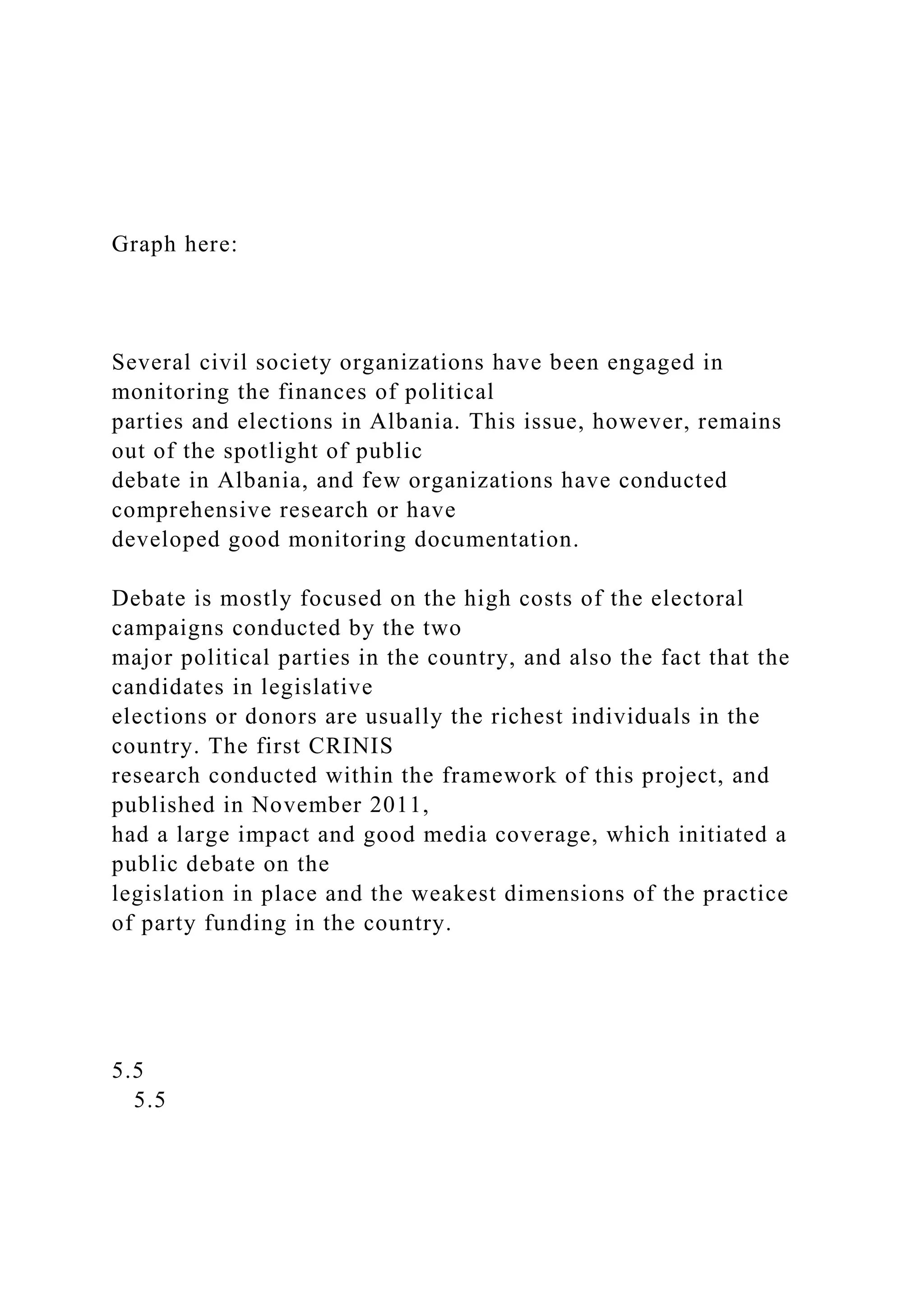

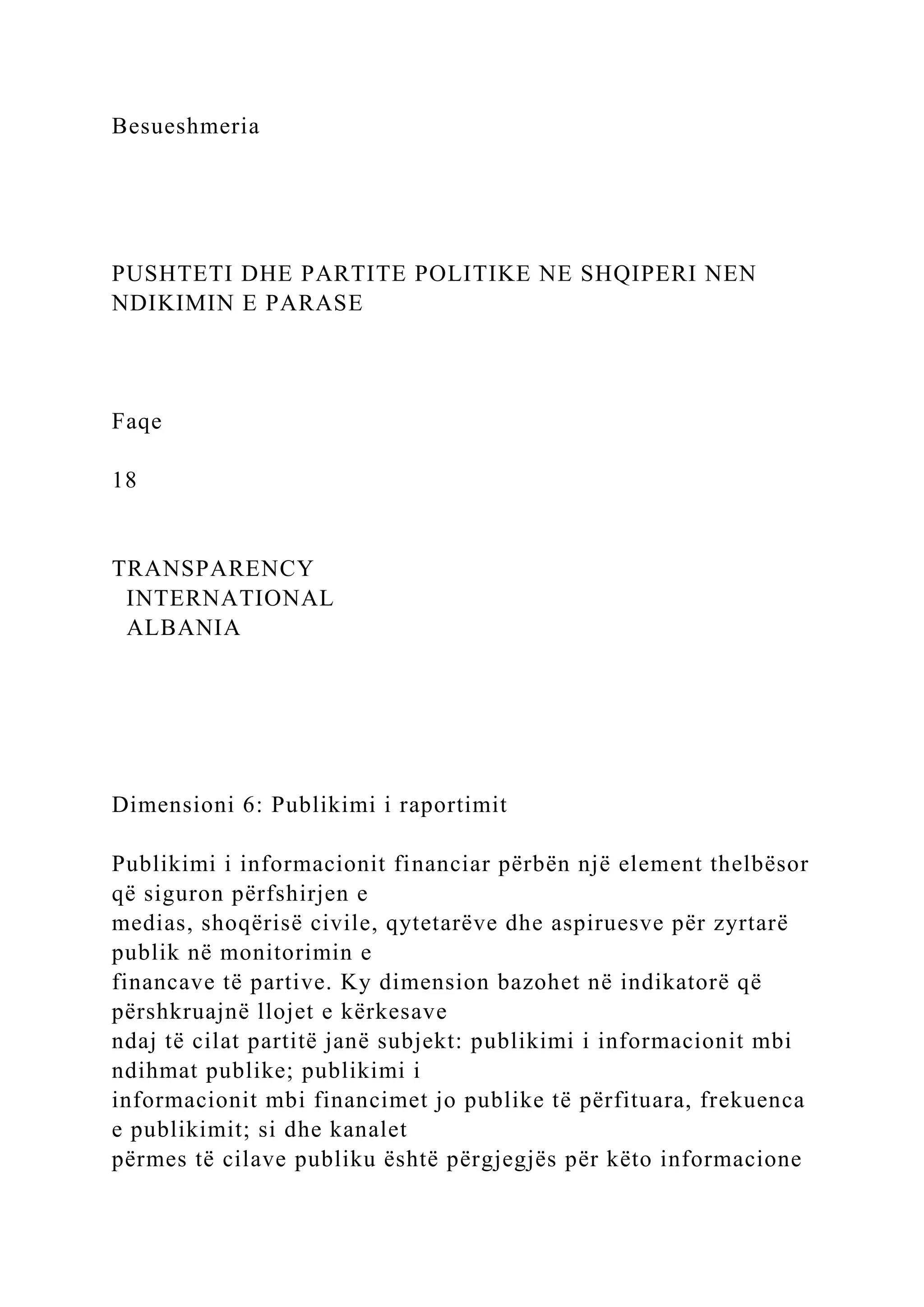

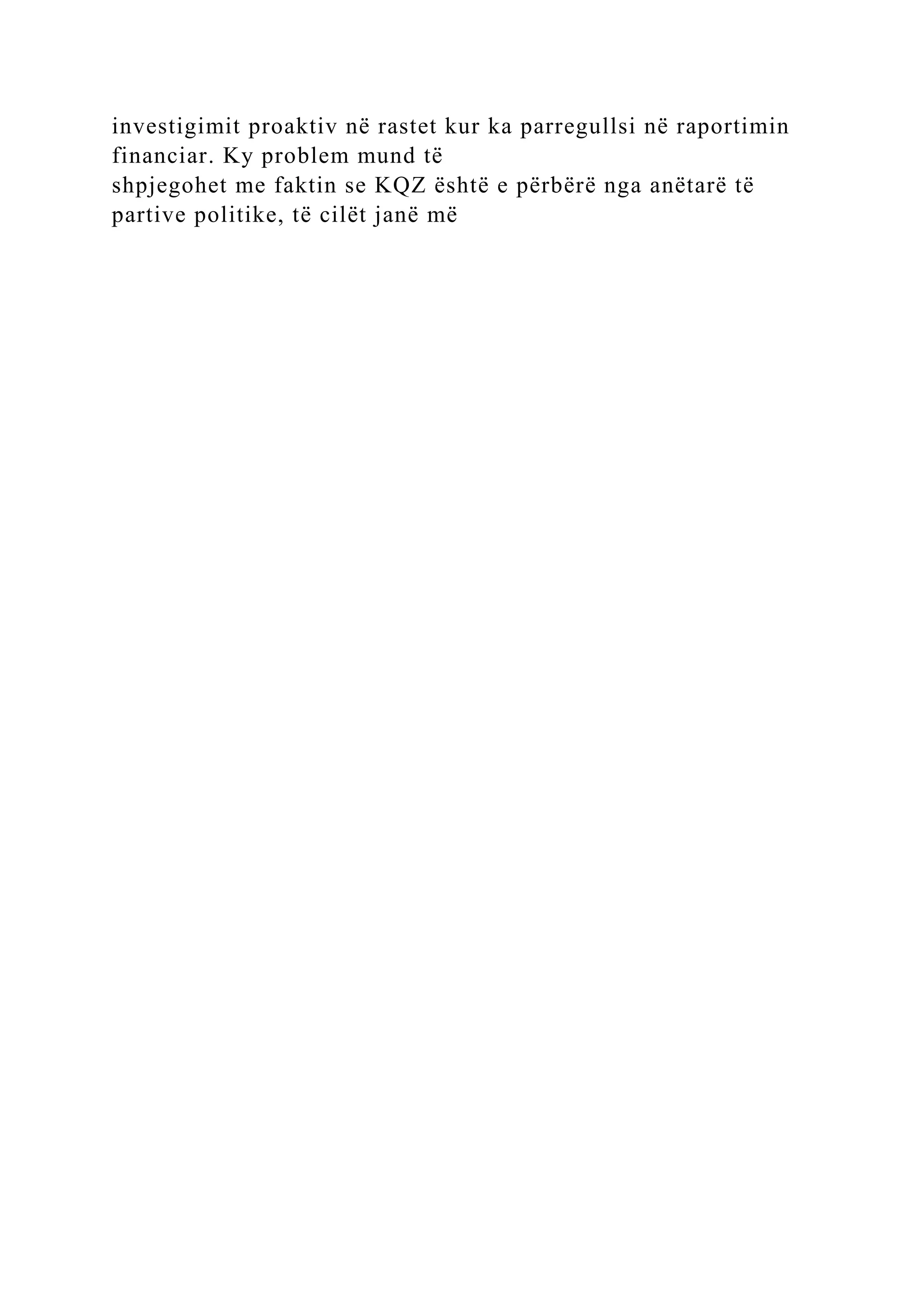

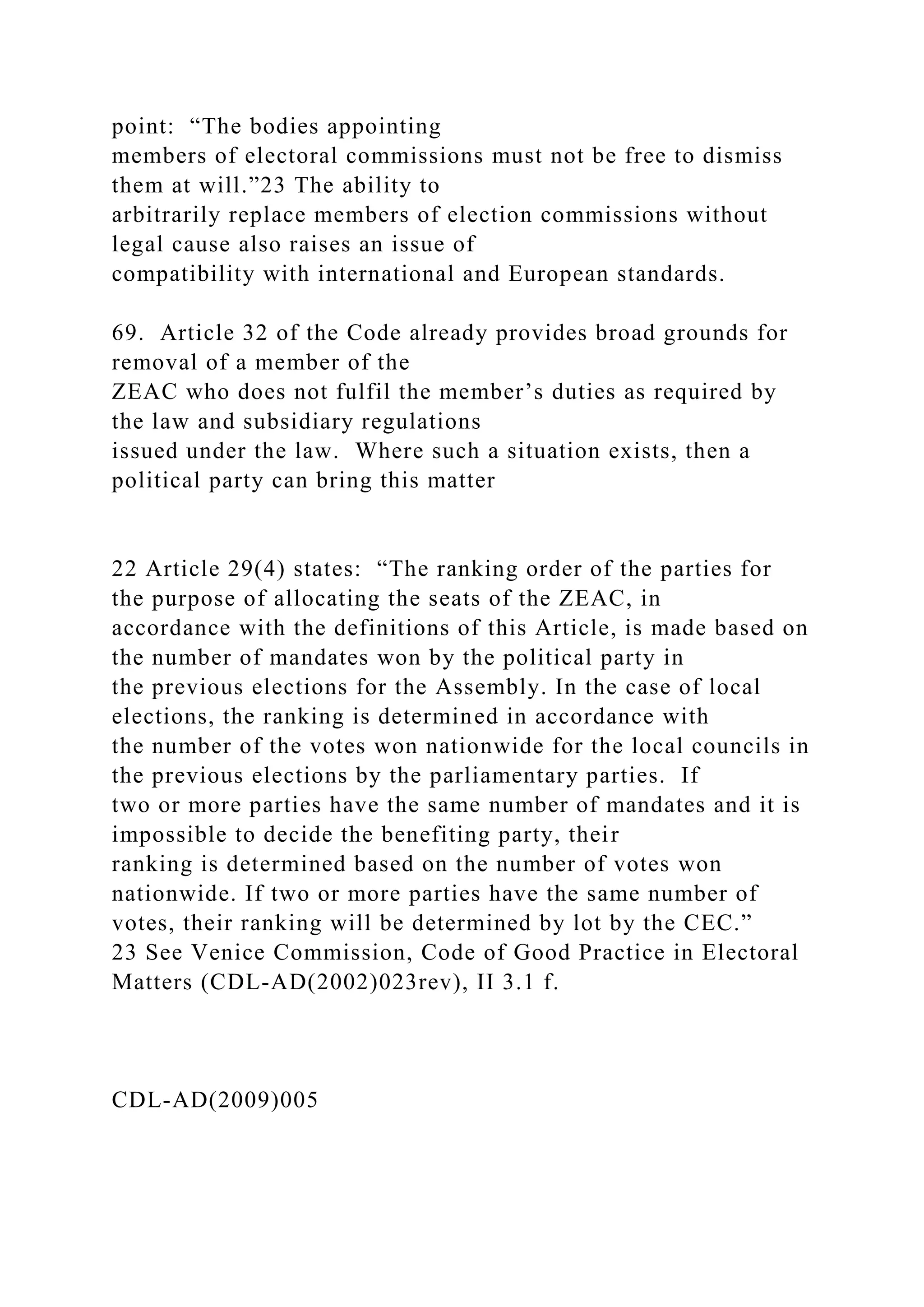

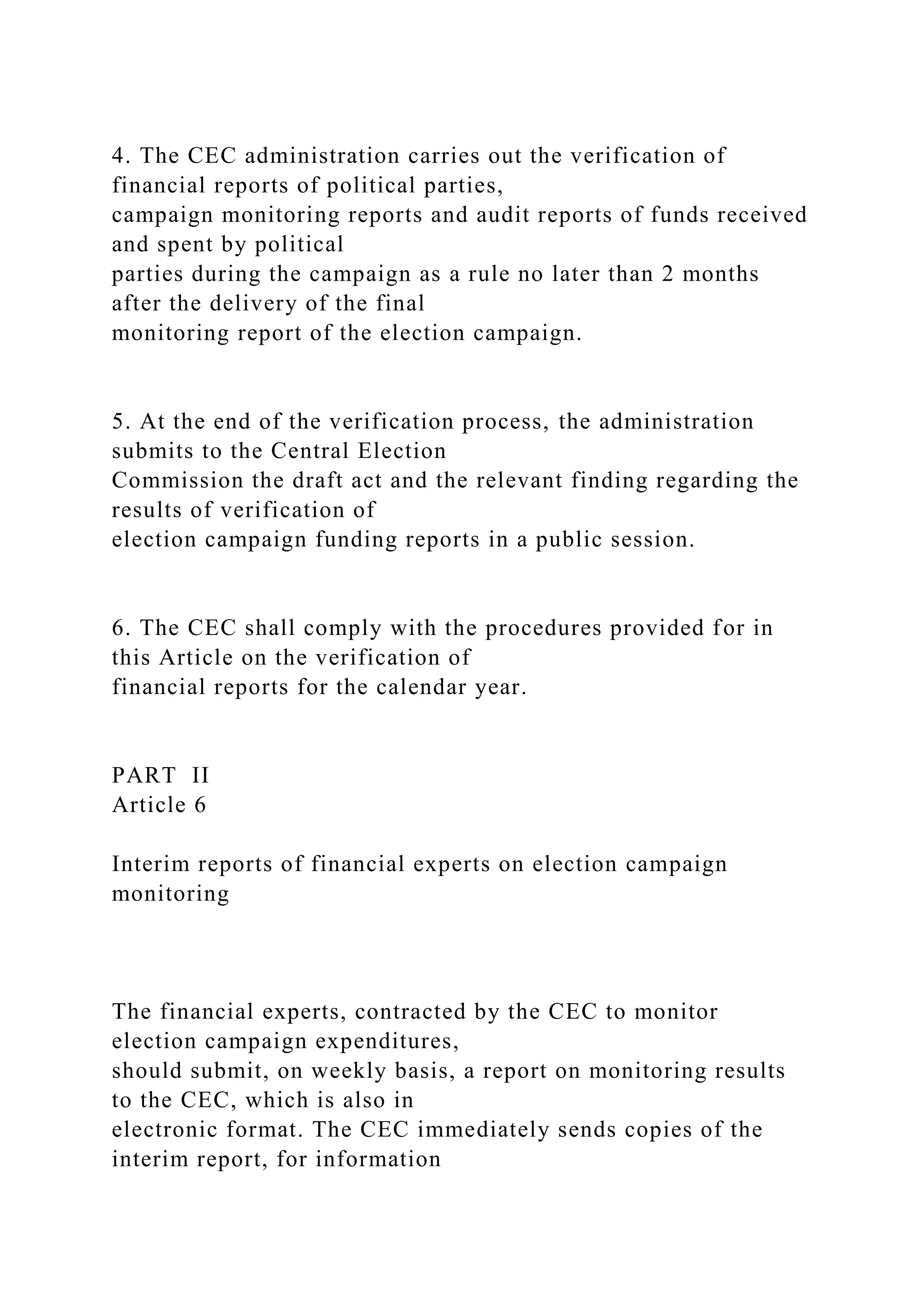

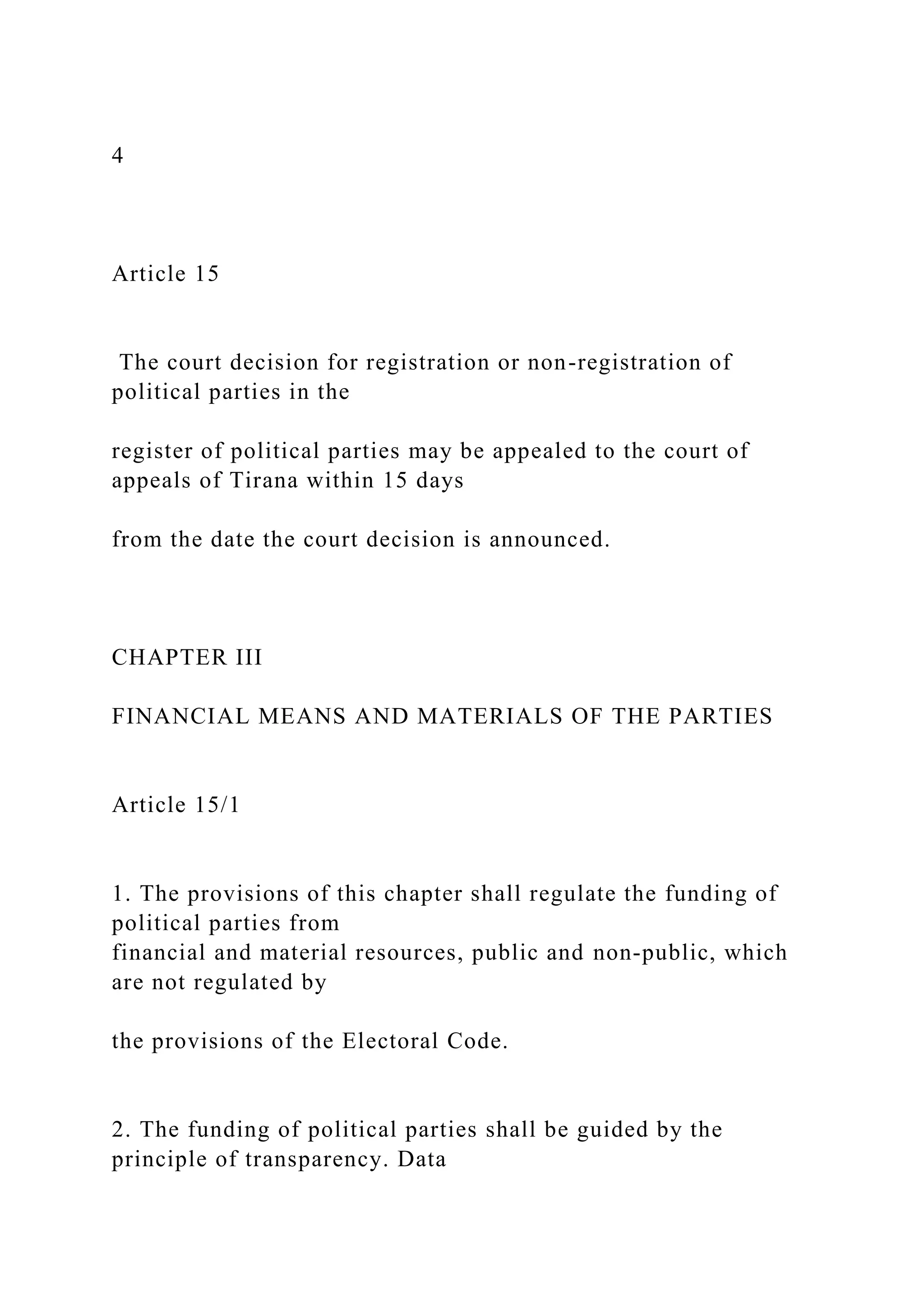

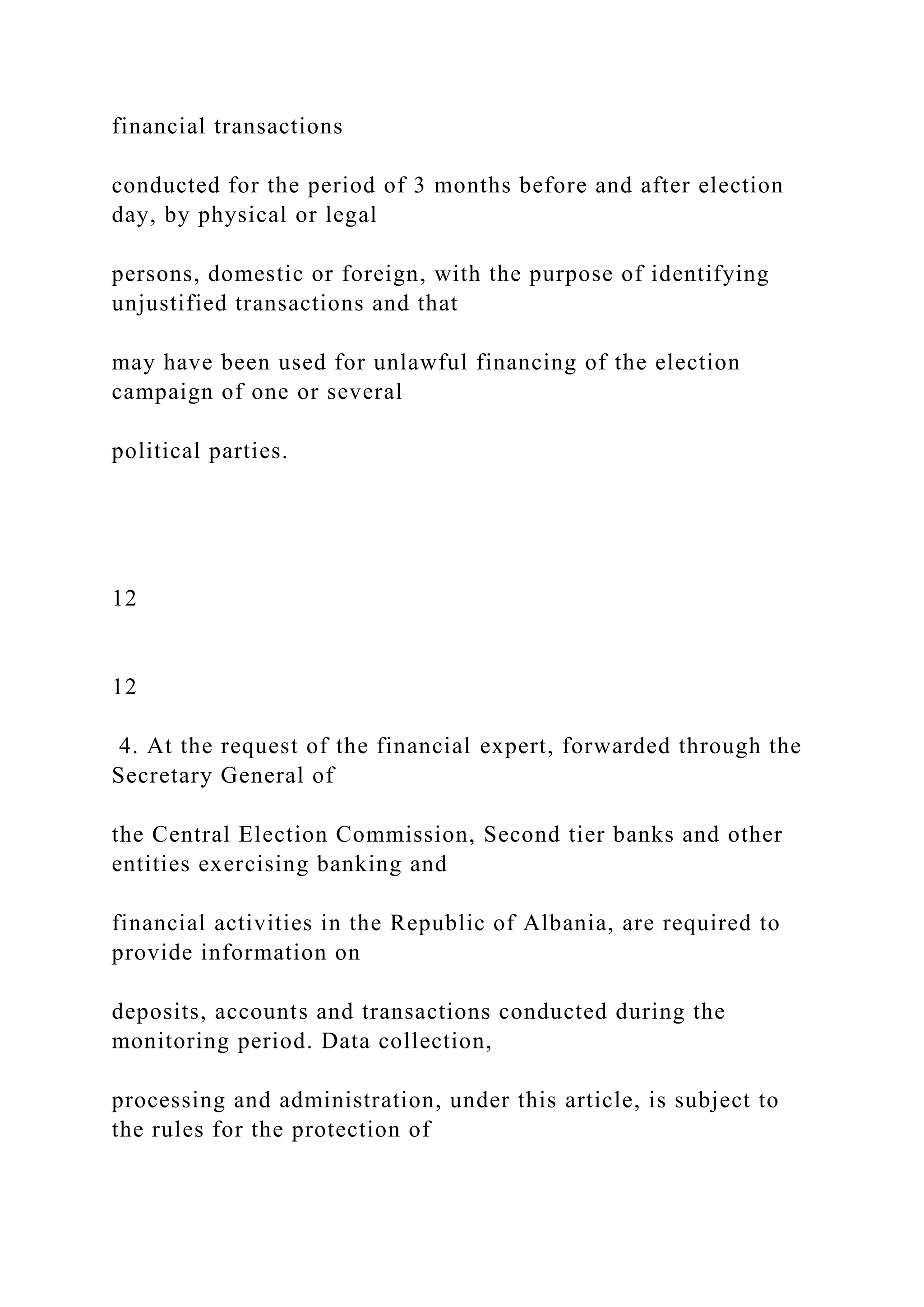

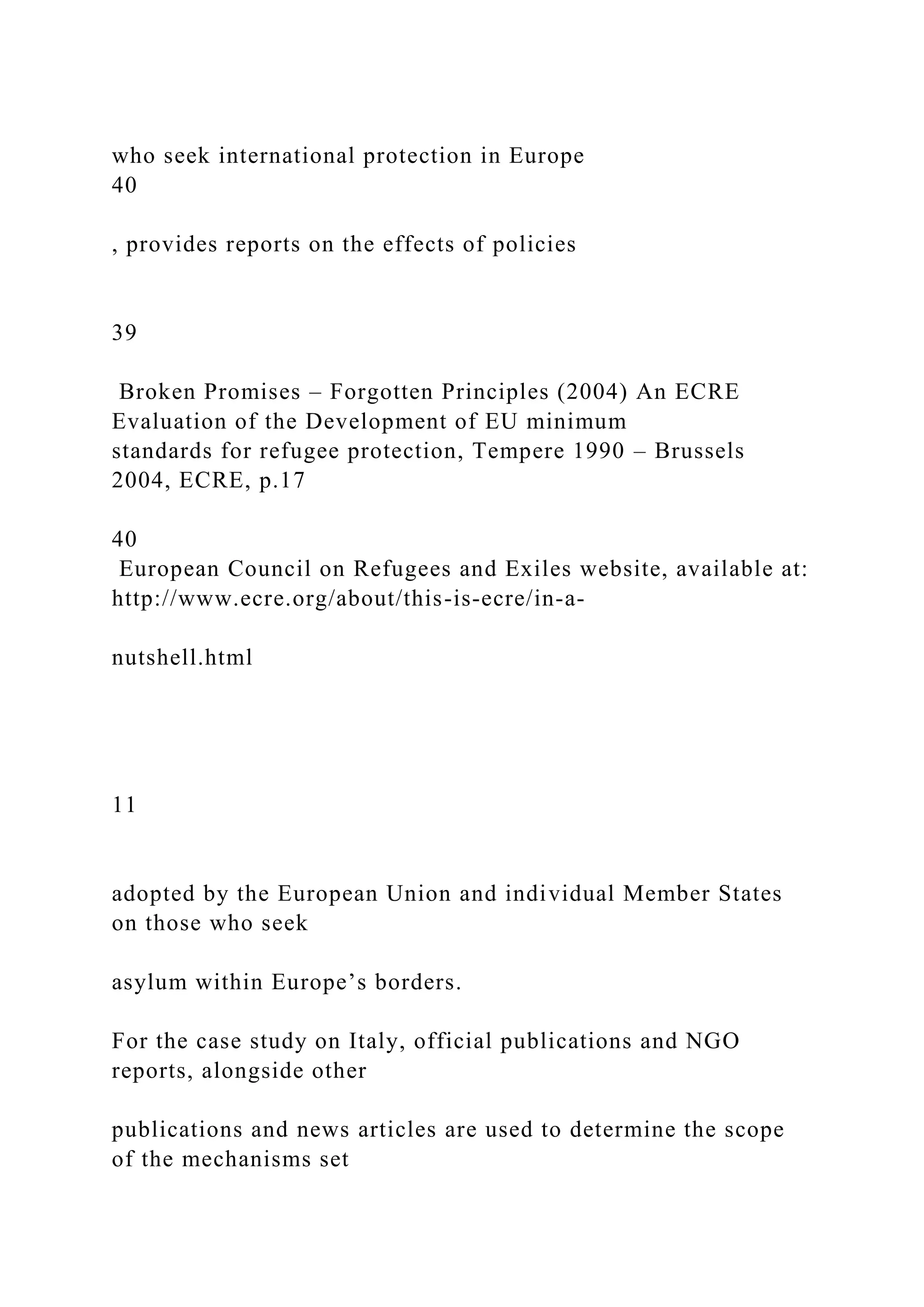

![3%

President

18%

Government

13%

Socialist Party

29%

Local SP

Government

7%

Democratic Party

21%

Local DP

Government

5%

Socialist Movement

for Integration

2%

Other Opposition

Parties

[PERCENTAGE]

Democratic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-108-2048.jpg)

![87(2) states that fifty percent (50%) of the public campaign

funds is “to be distributed among

political parties registered as electoral subjects and having seats

in the Assembly” “on the basis

of the number of mandates won in the elections for the

Assembly”. The remaining fifty percent

(50%) of public campaign funds “is to be distributed among

political parties registered as

electoral subjects and which have obtained not less than 2 seats

in the Assembly in the

preceding elections for the Assembly, in proportion with the

votes obtained by them

nationwide”. This text means that only parliamentary parties

are allocated public funds for the

elections. It is questionable whether the parliamentary parties

in the Assembly should give all

of the public funds for the electoral campaign to themselves.

The Venice Commission and

CDL-AD(2009)005

- 11 -

the OSCE/ODIHR recommend that these provisions be amended

to provide some public

funding mechanism for non-parliamentary parties.

42. Moreover, the second allocation is given to award the

winners by forcing the losers - those

who did not obtain any seat but had at least two seats in the

previous Assembly - to pay back

their initial allocation to the CEC [Article 87(2)b and 87(3)],

which re-allocates these funds](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-334-2048.jpg)

![among the winners [Article 87(5)]. This raises an issue of

concern since, ideally, it is hoped that

there are sufficient campaign funds for all electoral contestants

so that voters are fully informed.

It is unavoidable that some electoral subjects, who met the legal

requirements to be placed on

the ballot, will not be successful in the elections and will fail to

secure a mandate. These

electoral subjects should not now be punished. The system of

public funding for campaigns

fulfils the public policy objective of providing information to

voters about all electoral

contestants, even those that ultimately fail to win a mandate.

The Venice Commission and

the OSCE/ODIHR recommend that Articles 86 and 87 be

accordingly amended so that the

campaign funds of losers are not withheld and distributed

among the victors.

43. Articles 89 and 90 regulate the use of private funds for

electoral campaigns. Parliamentary

parties already have campaign funds due to the largess of the

Assembly under Article 86 and

87 of the Code. As noted above, non-parliamentary parties are

excluded from receiving public

funds and must rely solely on private donations. As a result,

parliamentary parties are not

impacted by Articles 89 and 90 as much as non-parliamentary

parties are impacted by these

articles. Article 90(3) limits campaign expenditures by tying

the expenditure limit to ten times

the largest amount of public funds given to a parliamentary

party. The problem with this

formula is that parliamentary parties can establish an

unreasonable expenditure limit by

reducing the amount of public funds parliamentary parties take](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-335-2048.jpg)

![19. Wolfgang Merkel, “Embedded and defective democracies”,

in

Democratization, Vol. 11, No 5, December 2004, p.51.

20. Merkel, p.49.

3. the state of Albanian

democracy

In a 2002 classification of democracies all over the world

Wolfgang Merkel, a well known political science scholar

for having coined the term ‘embedded democracies’ lists

Albania in the column of illiberal democracies19), pertaining

to his definition that illiberal democracies are:

Democracies with… “incomplete and damaged

constitutional state, where the executive and

legislative control of the state are only weakly

limited by the judiciary[…],constitutional norms

have little binding impact on government actions

democracies where the principle of rule of law

is damaged affecting the actual core of liberal

self-understanding, namely equal freedom of all

individuals.”20)

22

21. Democracy index ‘The Economist’ 2011; FRIDE (Fundación

para las

Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior) and Open

Society

Foundation , 2010.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-384-2048.jpg)

![times as well as by the way they are financed, the way

they mange institutionalized membership, etc.. Hence

the large quantity of these political parties in Albania

is directly connected to the ease that the Law offers.

For their large number, small electorate and the lack of

their representation both in parliament and at the local

[level] they display a lack of efficiency but I wouldn’t

say deformation. Deformation might be the case of the

law which offers this high degree of ease for them to be

created, but as long as ‘party’ means ‘piece’ then maybe

we have the desire to be in many ‘pieces’.

As long as the legal framework makes it possible for

political parties to be created and then go on without

institutionalized control, which would check if they have

a fixed office , without the institutional infrastructure,

register of members or even auditing for their funds,

this will act as a catalyst for ghost parties or parties that

appear only during election times. In the meantime, a

good part of them are simply one-man-party and don’t

have elected structures. From the legal perspective

opportunities should be created for parties to exert their

functions however there should be set some limits in

order for the process not to be rendered so ridiculous.

Geron Kamberi, expert on domestic political and

development issues

The Case of Albania

33

“Political parties are a national asset; the right to assemble

is an unlimited constitutional right. Some say we have too](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-394-2048.jpg)

![48

Mišo Dokmanović, PhD

Assistant Professor, Faculty of law, Ss. Cyril and Methodius

University, Skopje, Macedonia,

[email protected], [email protected]

www.pf.ukim.edu.mk

49

Political pluralism exists in Macedonia for

over 20 years. The country has experienced 7

parliamentary elections and as a result of that

the multi-party system has evolved over the

years with its own specifics.

The phenomenon of invisible ghost parties

existed in Macedonia for a considerable period

of time. In that direction, this paper makes an

attempt to analyze the role of the invisible,

ghost parties and their impact on election

results in the country.

A special emphasis will be put on the

case study of the Social Democratic Party

of Macedonia, its specific approach in the

parliamentary elections in 2006 and 2008 and

the lessons learned.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-411-2048.jpg)

![SDPM

5. State Electoral Commission. (2006). Final results of the

Parliamentary

elections in 2006. Available at: http://www.sec.mk/arhiva/2006_

parlamentarni/Rezultati_poIE_konecni.pdf. [Accessed on 15

April 2012].

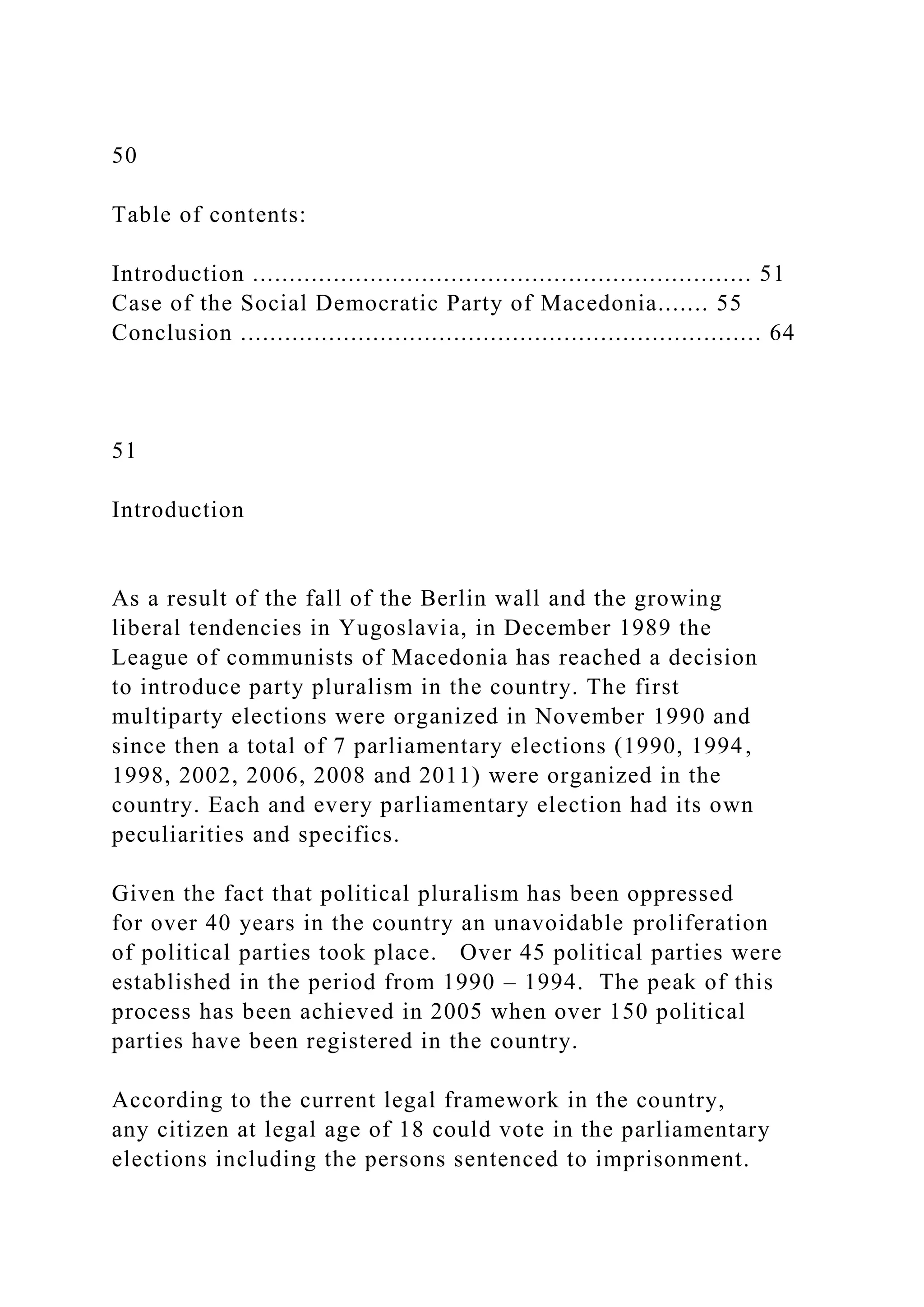

During the parliamentary election in 2006 the SDPM

has decided to nominate persons as lead candidates of the

party lists that had the same name and surname with the

candidates of the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia

(SDSM), the leading governmental party at the time of

elections. In that direction, it should be underlined that

the name and surname of the candidates of the leading

governmental party SDSM and the “ghost party” SDPM in

the electoral district 3 were the same – Nikola Popovski. At

the same time, the name and surname of the frontrunner

of the lists of both parties were almost identical – Ilinka

Mitreva for SDSM and Ilinka Mitevska for SDPM.

Explaining the role of the ghost parties in Macedonia

57

As a result of the similar party names and the almost

identical names of the party lead candidates, SDPM has

scored considerably better results than in the other electoral

districts. SDPM party score in electoral district 1, 2, 4 and

6 was at average level of 507 votes. On the other hand, in

the districts were the party had selected frontrunners with

almost identical names with the ruling party’ candidates

(electoral district 3 and 5) SDPM scored an average of 3098

votes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-418-2048.jpg)

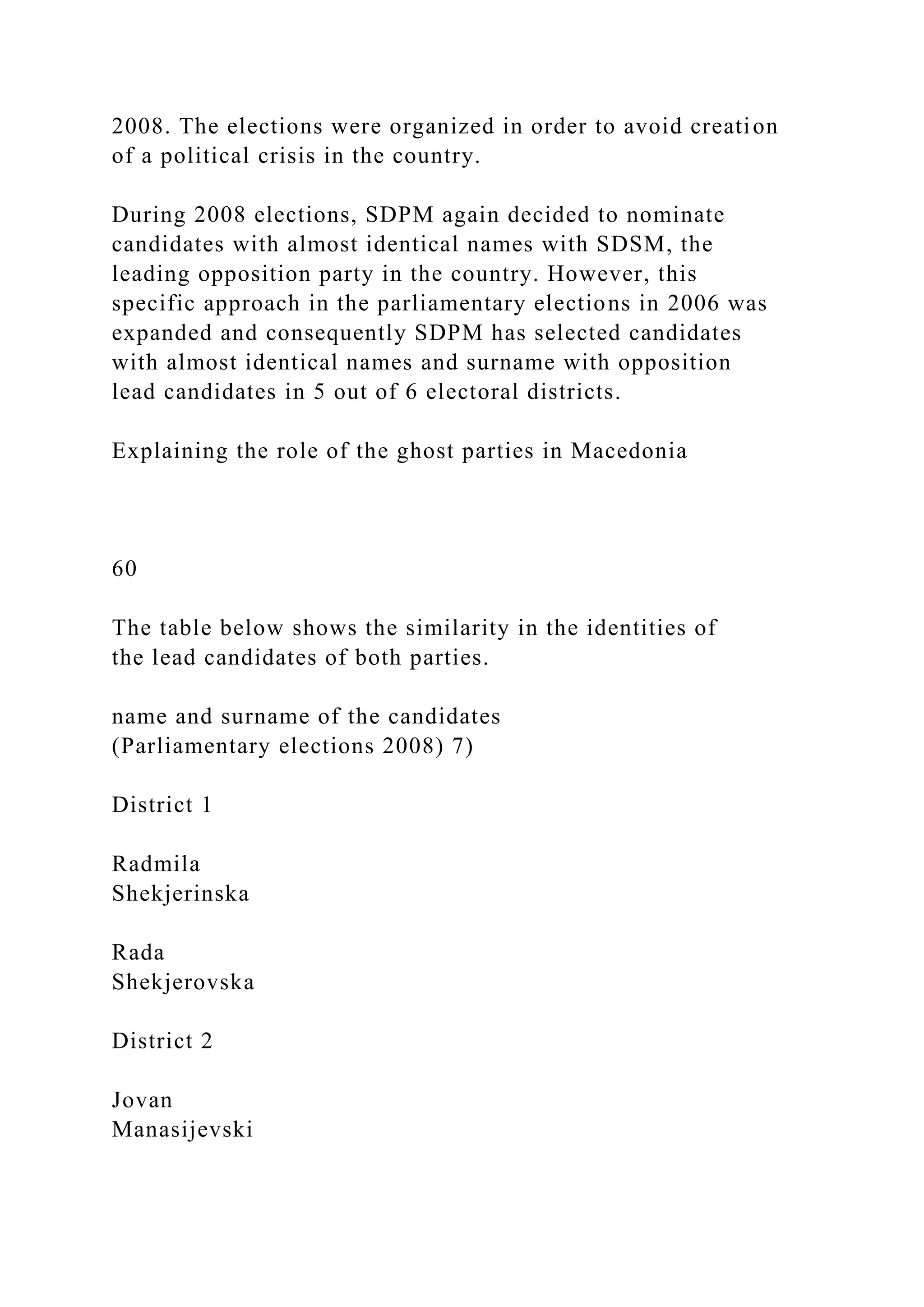

![Further analysis of this new emerging feature of the

Macedonian political systems has demonstrated that this

approach of the SDPM has not been limited to the number

of votes won only. In that direction, it should be emphasized

that this election score of SDPM has also affected the

distribution of the MP mandates in these two electoral

districts.

2006 Parliamentary Elections Results of SDPM by

electoral districts 6)

District 1 2 3 4 5 6

Votes 306 691 3564 775 2632 258

6. State Electoral Commission. (2006). Final results of the

Parliamentary

elections in 2006. Available at: http://www.sec.mk/arhiva/2006_

parlamentarni/Rezultati_poIE_konecni.pdf. [Accessed on 15

April 2012].

Explaining the role of the ghost parties in Macedonia

58

Given the fact that 20 mandates in each electoral district

are distributed according to the standard D’Hondt formula,

according to the final results the ruling party SDSM won 7

seats in the electoral district 3 and 6 seats in the electoral

district 5. However, if we added the surplus of the average

votes won by the SDPM in the other electoral districts, we

come to the conclusion that in the both cases, SDSM would

have won an additional seat in the parliament.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-419-2048.jpg)

![of twin candidates had the sole purpose to confuse SDSM

voters.8) Besides that, several TV stations have attempted to

interview the candidates of the SDPM, but in most cases,

when addressed, the candidates were not aware that

they were selected as lead candidates or declined media

interviews.

Given the fact that this approach of the SDPM

represented a clear manipulation of the election process,

the leading opposition party SDSM has filed a complaint to

the State Electoral Commission (SEC) against the registration

7. State Electoral Commission (2008). Early Parliamentary

Election 2008

– List of candidates. Available at:

http://www.sec.mk/arhiva/2008_

predvremeniparlamentarni/index/listinakandidati.htm.

[Accessed on 16

May 2012].

8. Utrinski Newspaper, 4 May 2008. Twins to Confuse SDSM

voters. Available

at:

http://www.utrinski.com.mk/?ItemID=CFFEFAF8FE0BE34D9D

83B52A31

5ED2B6. [Accessed on 21 May 2012].

Explaining the role of the ghost parties in Macedonia

61

of SDPM candidate list. As a result of that this approach

of SDPM became one of the main issues discussed during

the candidate registration and campaign period of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-424-2048.jpg)

![elections.

However, while regarding SDPM’s candidate list

was perceived as an attempt to confuse voters, the SEC

concluded that the Election Code did not provide grounds

for its rejection. Consequently, SDSM filed an appeal to

the Supreme Court of Macedonia. The Supreme Court has

dismissed the appeal on the grounds that “there was no

explicit right to such an appeal in the Election Code”.

The information that some of the candidates had not

been consented to be nominated was further investigated

by the Public Prosecutor office in Skopje. In that direction,

the Prosecutors office has requested from the police to

obtain information from the SDPM candidates. Given the

fact that no such information was received before Election

Day, the Skopje Prosecutor concluded that the candidates

in question had agreed to their candidacy. This incident has

been mentioned in the OSCE Election Observation Mission

Final Report.9)

Having in mind that the selection of lead candidates

of SDPM during the parliamentary elections in 2006 has

9. OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights.

(2008). Early

Parliamentary Elections – 1 June 2008 – Election Observation

Mission

Final Report. Available at

www.osce.org/odihr/elections/fyrom/33153.

[Accessed on 11 May 2012].

Explaining the role of the ghost parties in Macedonia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-425-2048.jpg)

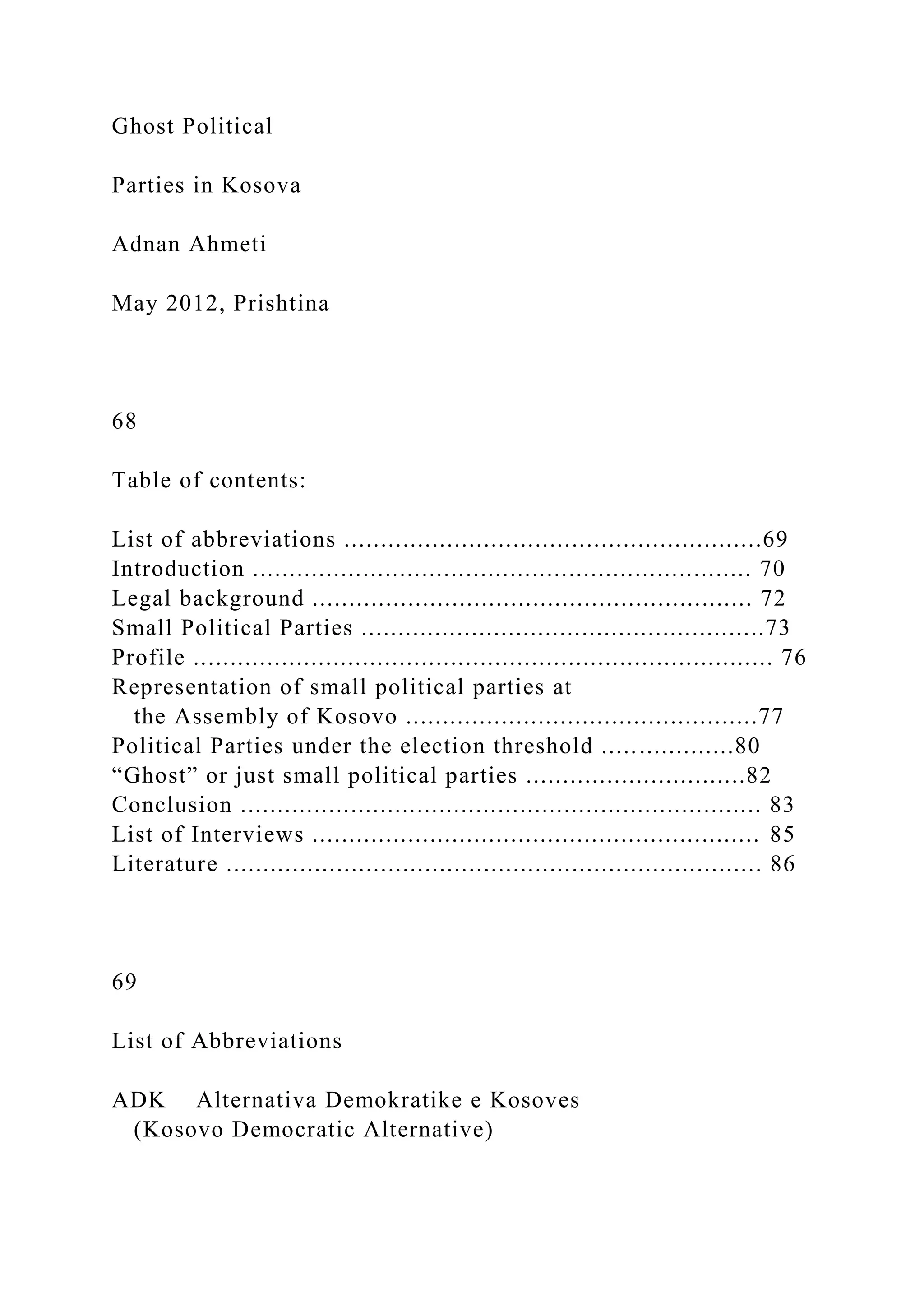

![62

affected the election results, I have further explored whether

this was the case with the parliamentary elections in 2008.

SDPM has won votes ranging from 465 – 1816 votes in the

six electoral districts in Macedonia. In that direction, after

the comparison of SDPM election results and the elections

results of the political parties that won a seat in the

parliament, a conclusion could be reached that the SDPM

votes did not affect the distribution of the seats in any of

the electoral districts in Macedonia in this parliamentary

election.

results of sdpm in the electoral districts

(Parliamentary elections 2008) 10)

District 1 2 3 4 5 6

Votes 1816 1203 1029 1300 593 465

10. State Electoral Commission (2008). Early Parliamentary

Election

2008 – Final Results by Electoral Districts.

Availableat:http://www.

sec.mk/arhiva/2008_predvremeniparlamentarni/fajlovi/rez_kone

cni/

Konecni03072008poIE.pdf.[Accessed on 18 May 2012].

It should not be forgotten that to a large extent this

outcome was due to the efforts of the leading opposition

party to prevent the events that occurred in 2006 when a

considerable number of its voters were misleaded with the

identity of the lead candidates. In other words, during the

campaign SDSM was unavoidably forced to concentrate its

energy and time to the complaint and appeal proceedings as

well as to voters’ education in order not to make the same](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-426-2048.jpg)

![political parties on democracy-building process in Kosovo.

I tried to make the difference between small political

parties and the parties as are called in political vocabulary

“Ghost Political Parties” 1). Small parties are indispensable

for democracy-building process or creating the basis for

democracy in an area that never experienced before the

democratic regime, and in no way they should be seen as

a single conglomerate. As you will see below, many SPPs

contribute a lot to the democracy and political landscape

of Kosovo.

Political parties are the engine of every democratic

endeavours, or better saying “the democracy is unimaginable

1. This term is borrowed from political parlance and it means

that “‘ghost

political parties’ are those political parties with dubious

membership

as questioned by their results in the elections (less votes than

minimum

number of members as required by law), little or no public

presence in

media and often not-to-be found headquarters/web pages/

leaders as well

as some other criteria.]”

Small and Ghost Political Parties in Kosova

71

without the existence of political parties”2). Therefore,

not only big political parties play or shall play a significant

role in emerging democracies, but also the small political

parties shall be very vigilant and proactive for promotion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-433-2048.jpg)

![close to the power. The closer to power, the more active

11. Interview with Leon Malazogu, ED, Democracy for

Development

12. Interview with Leon Malazogu, ED, Democracy for

Development

13. Based on the report of the Global Corruption Barometer

perceptions 2009

by Transparency International, the most corrupt institutions are

political

parties in Kosovo [Balkan Policy Institute -

http://policyinstitute.eu/alb/

areas/political_parties_and_elections/]

Small and Ghost Political Parties in Kosova

76

and more stable they are. Far away from the power their

existence increasingly is being called into question.

Profile

Small political parties in Kosovo are not grass-root parties14),

but they are parties more based on the cult of personality

of the leader – personalistic parties15). However, few of

them are well-structured in terms of their ideology and

programmes, but when it comes to run for power they forget

their ideology and programme and become part of coalition

to run for elections or part of government only according to

the slice of pie they get.

Profiling of political parties based on their ideological

orientation is not only a challenge for small political parties](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-439-2048.jpg)

![Unconstitutional activity of political parties is prohibited.

The determination of unconstitutional activity of a political

party and its prohibition is

decided by the Constitutional Court.

CHAPTER II

THE CREATION OF POLITICAL PARTIES

Article 9

The registration of political parties is done in the court of the

first level of the district

of Tirana, which keeps the register of political parties. In the

registry of political parties there

is indicated: the numerical order of registration, the protocol

number [number of the official

document], the number of the judicial decision, the date of

announcement, the disposition of

the decision, the full name of the party, the initials of the party,

the emblem of the party, a

description of the configuration of the seal, the name of the

chairman, notes about the change](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-467-2048.jpg)

![on the parties’ financial resources and expenses shall be

published at any [given] time.

3. The rules on monitoring, supervision and auditing of

financial and material resources

must observe at all times the equality of political parties before

the law and must not

infringe their right to be established freely.

Article 15/2

1. The Central Election Commission is the body responsible for

the monitoring and

supervision of the funding of political parties according to the

rules of this law.

2. The Central Election Commission, based on and in order to

implement this law, has

the following competencies:

a. It drafts and adopts both rules on reporting of funding, on

monitoring, supervision and

financial auditing of political parties, and standardised

templates of annual financial

reporting;

b. It approves both the template of the special record book

[register] of non-public funds](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-473-2048.jpg)

![parliamentary

elections;

c) 10 percent shall be divided according to the percentage

obtained among [by] the

political parties that took part in the last parliamentary elections

and obtained over

1 percent of the votes.

The non-allocated remainder of the 10 percent shall be added to

the 70 percent fund

and it shall be divided among parliamentary parties.

3. The concrete amount of the public fund received by each

political party in the form of

annual financial aid in compliance with this law shall be

determined by a decision of the

Central Election Commission. Both the beneficiary political

parties and Ministry of Finance

shall be notified of this decision.

4. In any case, annual financial aid shall be awarded on the

proviso that political parties have

already submitted the financial report of the preceding year

according to the rules defined by](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-477-2048.jpg)

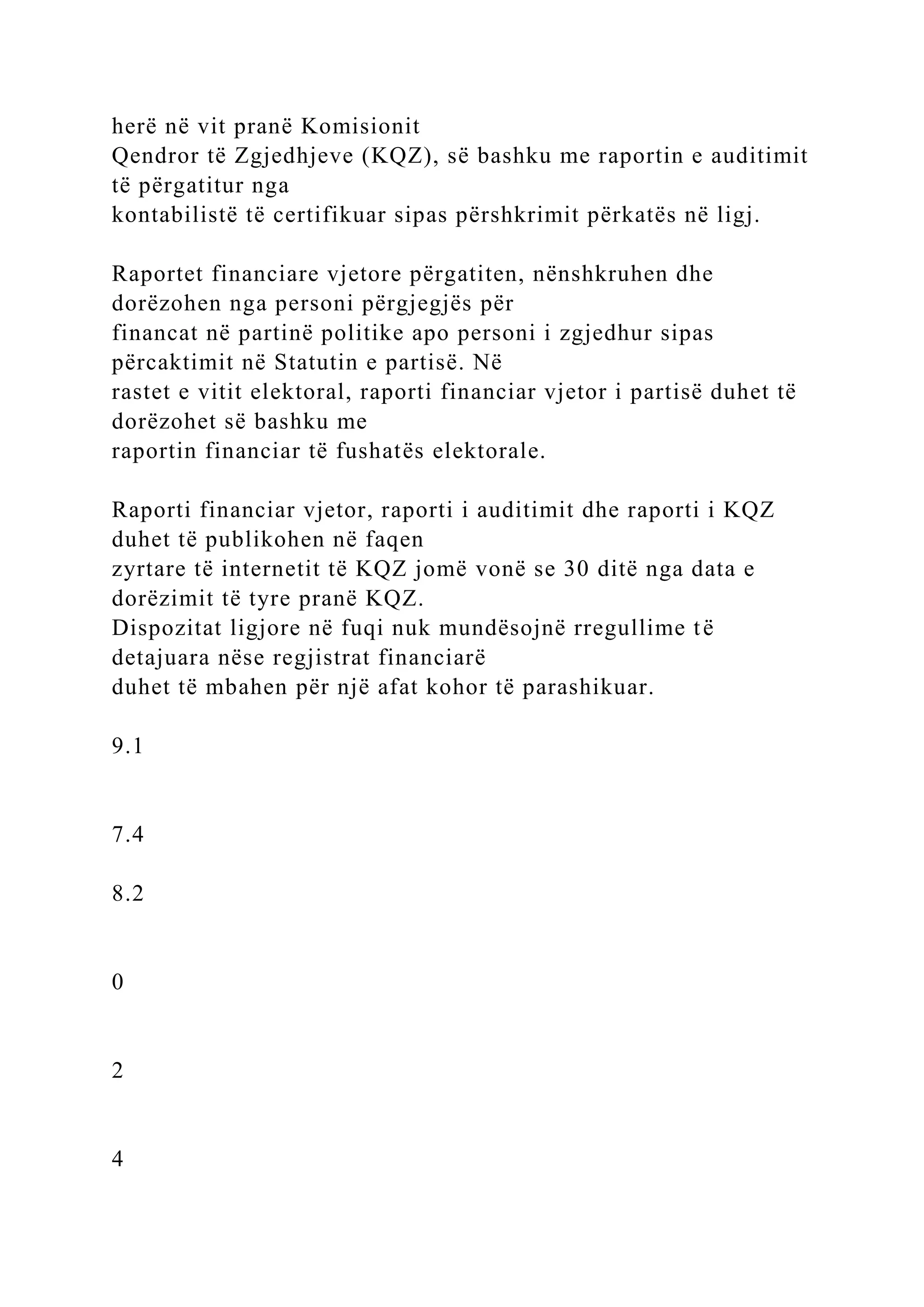

![3. Political parties shall submit the annual financial report along

with the auditing report

drawn up by certified accounting experts in accordance with the

provisions of this law.

4. The annual financial report shall be submitted either by the

person in charge of finances

at the political party or by an individual assigned [to carry out

this duty] by the statute of

the political party within the timeframe defined by the Central

Election Commission.

5. During an election year, the financial reports of the political

party must be submitted with

the financial report of the election campaign.

6. The annual financial report, the report of the certified

accounting experts, the financial

report of the election campaign and the report of the Central

Election Commission shall

be published in the official website of the Central Election

Commission no later than 30

days from the date of their submission by the political party”.

Article 23/1

1. Each political party must record in a special record book,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-483-2048.jpg)

![according to the template

approved by the Central Election Commission, the amount of

funds received by any

natural or legal person, and data clearly defining the identity of

the donor. When

awarding the donation, the donor shall at all times be obliged to

sign a donation

statement, in accordance with the template approved by the

Central Election Commission.

8

8

The list of persons who donate funds of not less than one

hundred thousand ALL along

with the respective amount [donated] shall be made public at all

times.

2. The donation of non-public funds in excess of one hundred

thousand ALL must be made

only through a special bank account opened by the political

party. The person in charge

of finances at the political party shall notify the Central

Election Commission of the bank](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-484-2048.jpg)

![2. The expenses needed to audit the political parties shall be

covered by the political parties

themselves. Political parties shall transfer the sums needed for

this purpose to the bank

account of the Central Election Commission. Detailed rules on

the running of this process

shall be defined by way of an instruction issued by the Central

Election Commission.

Article 23/4

1. The infringement of the provisions of the funding of political

parties by the person in

charge of finances within the political party or the individual

assigned by the party statute

[to carry out this duty] shall be punishable by a fine of 50 000

to 100 000 ALL.

2. The infringement of the obligation of the political party to

cooperate with the certified

accounting expert assigned by the Central Election Commission

shall be subject to a fine

of 1 000 000 to 2 000 000 ALL.

3. Failure or refusal to make the financial sources of the

political party transparent or to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-488-2048.jpg)

![YOUR RESPONSIBILITY TO CONTACT THEM

Seeking advice from other members of staff

You can also ask for specific advice from other members of

staff as long as you do not expect the other person to replace the

supervisor

Academic Tutor

For additional academic support, contact [email protected]

Administrative questions,

please contact [email protected] (T1); [email protected] (T2)

6

Questions?

7

Feedback

What was one piece of positive feedback you received on

IP2021

What was one thing you were told to improve on IP2021?

The Research Process](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-515-2048.jpg)

![, rather than liberal, democratic and humanitarian responses

supposedly

working under an umbrella of supranationalism. As a result,

European borders pose as

‘highly differentiated border zones [...] of highly perforated

systems or regimes’

2

, with

decision making driven by individual Member States’ interests,

portraying the Union as

incapable of adequately responding to flows of asylum seekers

attempting to reach its

borders.

Despite the common belief that this inability results from the

reluctance of Member

States to assume responsibility, or their concerns over the

notions of sovereignty and

power, the fact that European borders have been ‘more real for

most non-OECD

national than for members of OECD countries’

3

calls for different explanations.

Exclusionist policies of the European asylum regime divide

global society into groups of

‘Us’ and ‘Them’, whereby a ‘civilised European order is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-530-2048.jpg)

![situated like an island within a

threatening sea of starving, brutalised, but determined-because-

desperate inferior

peoples’

4

aiming to find refuge within European borders.

1.1 Research Questions

This paper seeks to unveil the space created by the European

asylum regime to allow

Member States to choose the preferred and exclude unwanted

asylum seekers,

adopting an essentialist concept of the nation through a lens

which argues that ‘if your

race or culture or religion does not fit the parameters, then you

cannot belong’

5

. By

implementing barriers to entry for specific groups of asylum

seekers, the European

Union allows the ethnic nationalist sentiments of its Member

States to guide policy on

asylum down a path of social exclusivity whereby Europe is

created ‘less as a

cosmopolitan melting pot and more [as] a white fortress’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-531-2048.jpg)

![of this Directive cannot establish an absolute guarantee of

safety for nationals

of that country. [...] For this reason, it is important that, where

an applicant

shows that there are serious reasons to consider the country not

to be safe in

his/her particular circumstances, the designation of the country

as safe can

no longer be considered relevant for him/her’

64

However, the application of the right of specific groups of

refugees to seek asylum by

providing reasons to consider that a third country is not safe for

his/her particular

circumstances is increasingly sidelined by the general

application of the regulation. This

is particularly evident when further examination of regional and

thematic approaches to

the notion of asylum is conducted.

Hence, a Communication from the Commission describing a

strategy on the External

Dimension of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice

highlights the importance of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-573-2048.jpg)

![2000/0238 (CNS), p.4

65

Chapter V of the Communication from the Commission: A

Strategy on the External Dimension of the Area of

Freedom, Security and Justice COM(2005) 491 final

17

building such as a fundamental overhaul of the judiciary, and

the

development of border management and an asylum system in

line with

European standards. With the Mediterranean countries,

strengthening good

governance and the rule of law as well as improving migration

management and security are the main goals. [...] Migration and

border

management are at the top of the agenda, and partnerships

should be

strengthened in the region with countries of origin and transit.

Further

progress is necessary on readmission agreements, and efforts to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-575-2048.jpg)

![entry on the same grounds’

76

Therefore it is not applying for asylum, but reaching the

territory of the European Union in

order to do so that is extremely difficult. With the erection of

carrier sanctions and strict

border check mechanisms, the European Union has closed off its

borders to migrants

and therefore would-be asylum seekers from Africa and Asia,

revealing the biopolitical

patterns of European migration and asylum policies. Thus,

despite the Schengen

Borders Code Regulation encompassing a clause stating that

‘by way of derogation from paragraph 1[...] (c) third-country

nationals who do

not fulfil one or more of the conditions laid down in paragraph

1 may be

authorised by a Member State to enter its territory on

humanitarian grounds,

on grounds of national interest or because of international

obligations’,

77

those attempting to reach Europe from Africa and Asia are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-588-2048.jpg)

![31

[future] focus of maritime attention lay: the Mediterranean Sea’

114

. Despite Article 31 of

the 1951 Refugee Convention recognising that asylum seekers

may enter the territory of

a signatory State without authorisation

115

, their very attempt to reach the territories of the

European Union is prevented, with their illegal status used to

disqualify their rights

116

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-622-2048.jpg)

![5.6 Thematic Programmes

The Thematic Programmes of the European asylum regime are

erected with the aim of

setting clear principles and objectives for the Union’s

engagement with third countries. At

the same time, they serve the purpose of reducing ‘the burden of

control at their

[Member States’] immediate borders and increases the chances

of curtailing unwanted

inflows before they reach the common territory’

119

. As such, by analysing where the

focus of these is placed and what kind of action is prescribed, a

better understanding of

the Union’s objectives concerning specific regions, and thus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-626-2048.jpg)

![seekers are not given the opportunity to lodge an application for

protection. Even if such

action was taking place, the CPT Report highlights that even if

protection was requested

aboard an Italian vessel, ‘there is no procedure in place capable

of referring him/her to a

protection mechanism’

133

. Meanwhile, Berlusconi was quoted by the Italian media saying

that the Italian idea it to ‘take only those citizens who are in a

position to request political

asylum [...] referring to those who put their feet down on our

[Italian] soil’

134

. This is

apparently a shared view across the Union demonstrated by the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-643-2048.jpg)

![ethnic nationalism and calls for greater social cohesion,

instituting a biopolitical

apparatus and shifting from a ‘system designed to welcome

Cold War refugees from the

East and to resettle them as permanent exiles in new homes, to a

non-entree regime,

designed to exclude and control asylum seekers, [especially]

from the South’

146

.

144

Bhabha, J. (1998) ‘Get Back to Where You Once Belonged’:

Identity, Citizenship and Exclusion in Europe,

Human Rights Quarterly, vol.20 no.3 p.598

145

Muller, J. (2008) Us and Them: The Enduring Power of Ethnic

Nationalism, Foreign Affairs, vol.87 no.3 p.19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-658-2048.jpg)

![Official documents:

1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of

refugees, UNHCR, available at:

http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html [accessed March 2,

2012]

AENEAS programme: Programme for financial and technical

assistance to third counties

in the area of migration and asylum, Overview of projects

funded 2004-2006, European

Commission, available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/what/migration-

asylum/documents/aeneas_2004_2006_overview_en.pdf

[accessed April 15, 2012]

Commission Staff Working Paper: Report on Progress Made in

Developing the

European Border Surveillance System (EUROSUR) SEC(2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/httpsifes-221015083553-d170a478/75/httpsifes-orgsitesdefaultfilesbrijuni18countryreport_fi-docx-661-2048.jpg)