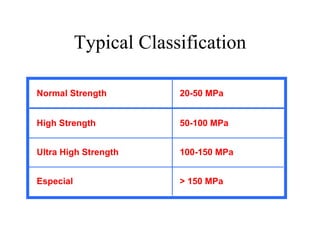

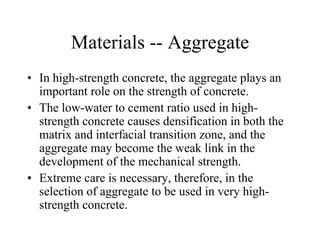

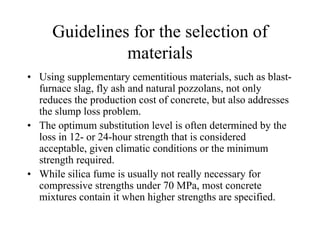

This document discusses high-strength and high-performance concrete. It notes that high-strength concrete is defined based on compressive strength, while high-performance concrete must meet additional requirements of workability, durability and strength. The document outlines typical classifications of concrete strength and discusses the microstructure, materials, mechanical behavior, and applications of high-strength concrete. It provides examples of the Petronas Towers, which used 40-80 MPa concrete and realized structural economy and simplified construction through the use of high-strength concrete.

![Definitions

• The definition of high-performance concrete

is more controversial.

• Mehta and Aitcin[1] used the term, high-performance

concrete (HPC) for concrete

mixtures possessing high workability, high

durability and high ultimate strength.

[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hsc-141128093420-conversion-gate01/85/Hsc-2-320.jpg)

![Definitions

• ACI defined high-performance concrete as

a concrete meeting special combinations of

performance and uniformity requirements

that cannot always be achieved routinely

using conventional constituents and normal

mixing, placing, and curing practice.

[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hsc-141128093420-conversion-gate01/85/Hsc-3-320.jpg)