The document discusses HPV vaccination, including:

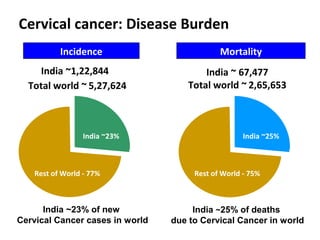

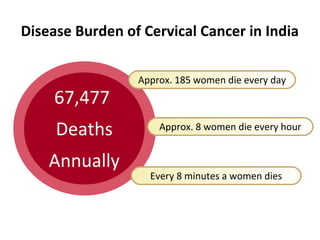

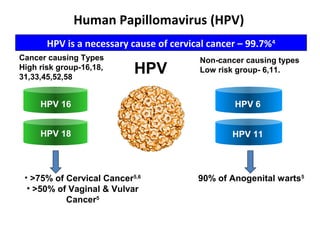

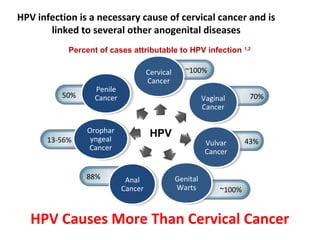

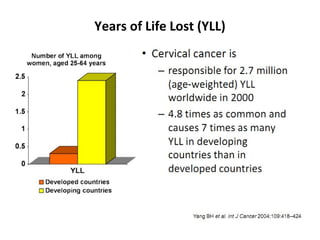

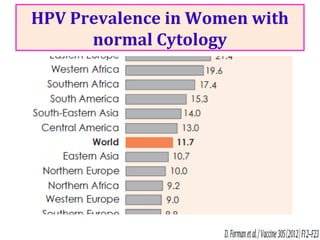

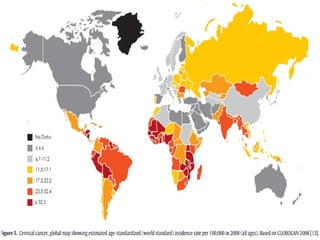

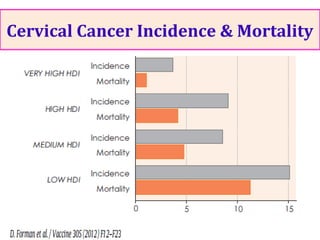

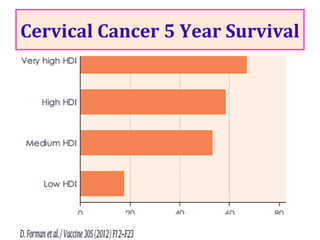

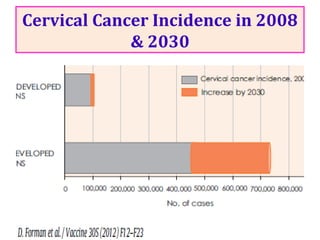

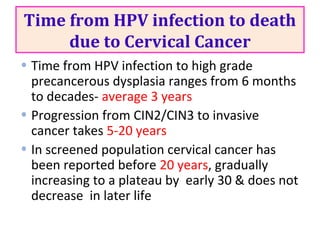

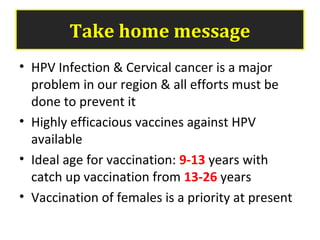

1) Cervical cancer is a major disease burden in India, with India accounting for about 25% of cervical cancer deaths worldwide. HPV is the cause of nearly all cervical cancers.

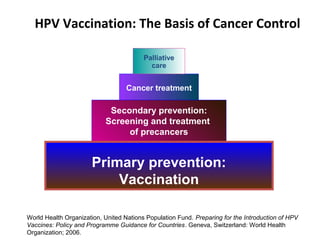

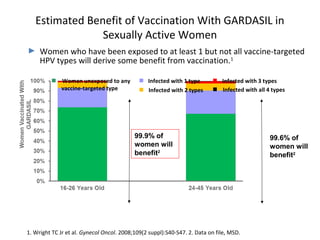

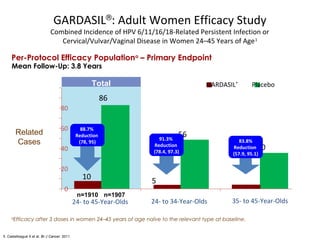

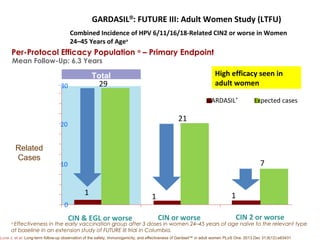

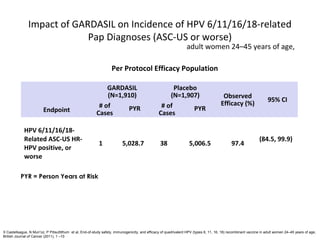

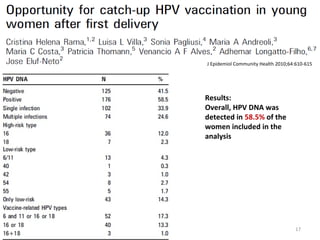

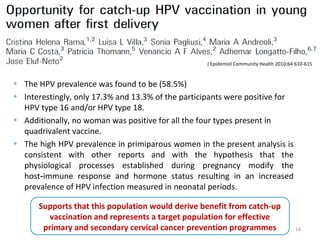

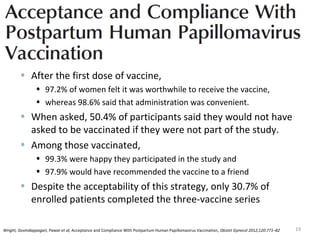

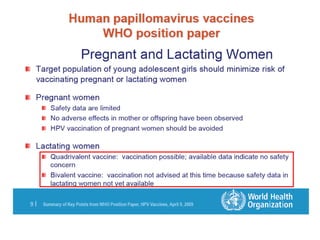

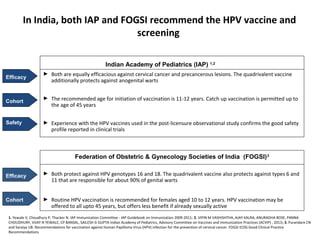

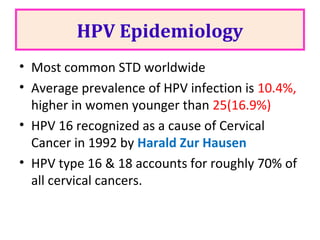

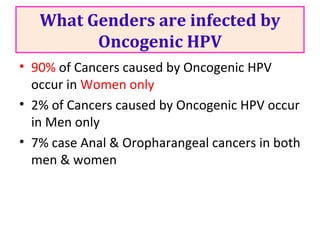

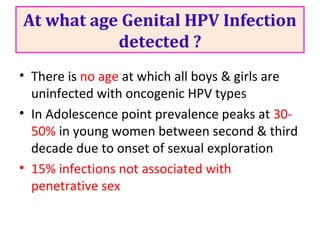

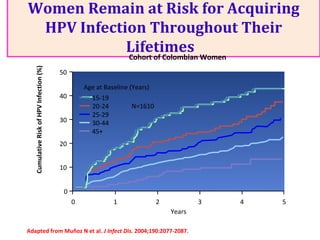

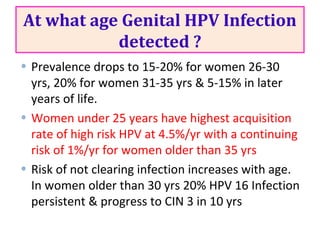

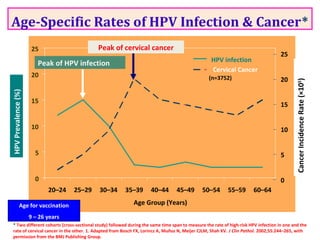

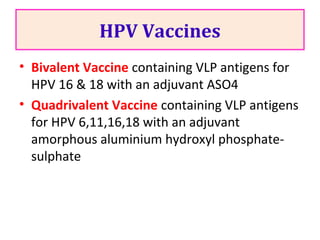

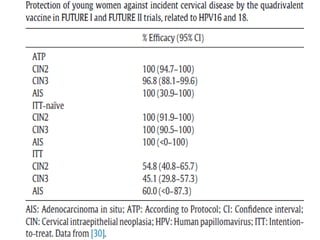

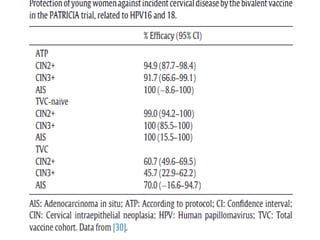

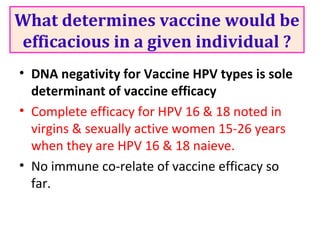

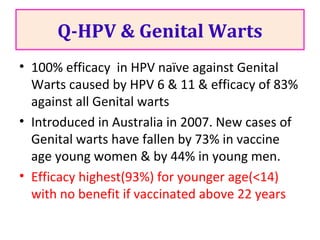

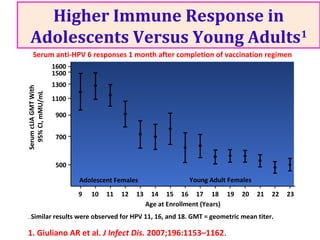

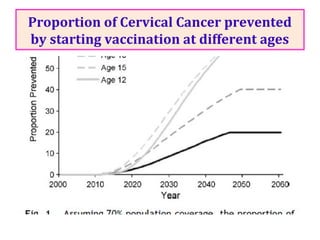

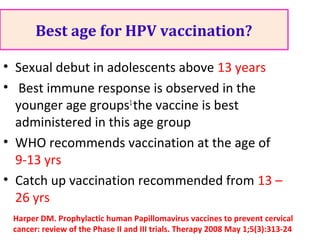

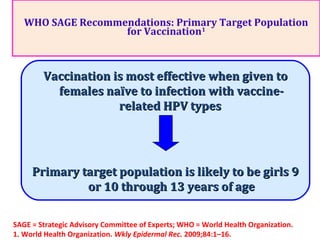

2) HPV vaccination aims to prevent cervical cancer by vaccinating against HPV types 16 and 18, which cause about 70% of cervical cancers. Vaccination is recommended for girls and women between ages 9-45 before sexual debut or exposure to HPV.

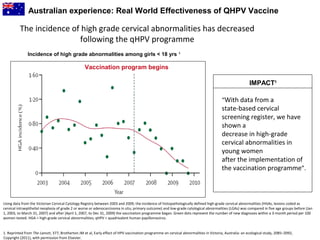

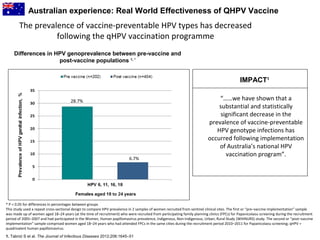

3) Real-world effectiveness data from Australia's HPV vaccination program shows decreases in HPV vaccine-type infections and high-grade cervical abnormalities in young women following the program.